Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mirzajani A, Barat A, Abolghasemi J. Intraocular Pressure Changes Before and After Presbyopic Optical Correction in Early Presbyopic Adults. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-312-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-312-en.html

1- Department of Optometry, School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. , Mirzajani.a@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Optometry, School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Optometry, School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 521 kb]

(51 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (252 Views)

Full-Text: (40 Views)

Introduction

Presbyopia, a prevalent age-related condition marked by progressive accommodative decline, affects over one billion people globally and is expected to increase substantially as the global median age continues to rise [1]. By 2050, presbyopia will likely constitute a significant public health burden, particularly in middle-aged populations actively engaged in occupational and social activities requiring sustained near vision [2].

Clinically, presbyopia manifests as the eye’s reduced ability to focus on close objects, leading to eye strain, blurred near vision, and difficulty performing daily tasks [3, 4]. The pathophysiology involves decreased elasticity of the crystalline lens, weakening of the ciliary muscles, and altered biomechanical response of the zonular fibers [5]. While the functional impairment is well-documented, its broader implications, including potential changes in intraocular physiology, remain underexplored [6].

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is a central parameter in ocular health maintenance [7]. It is primarily influenced by the dynamic equilibrium between aqueous humor production by the ciliary processes and its outflow through the trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral pathway [8]. Sustained elevation in IOP is a major risk factor for glaucomatous optic neuropathy [9]. Even modest changes in pressure can have implications for individuals predisposed to ocular hypertension [10].

Newly presbyopic individuals, particularly those reluctant to adopt corrective measures, often attempt to overcome near-vision challenges by increasing accommodative effort [11]. This compensatory mechanism can lead to structural and functional changes in the anterior segment, including increased tonus of the ciliary body, narrowing of the anterior chamber angle, and potential interference with aqueous outflow [12, 13]. These anatomical and physiological responses may contribute to transient IOP elevation [14].

In contrast, some literature suggests that tasks involving sustained accommodation, such as reading or near work, may lead to a temporary reduction in IOP, possibly via changes in uveoscleral outflow or muscular tonus modulation [15]. However, results remain inconsistent and context-dependent, highlighting the necessity of focused investigation [16].

This study aims to determine the relationship between initial presbyopic correction and IOP modulation in newly presbyopic adults. By analyzing IOP changes before and after near correction, the research addresses a gap in current understanding. It provides a foundation for future studies in ocular biomechanics and preventive eye care.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This observational, cross-sectional study was performed in 2024 at the Optometry Clinic of Samen Specialty Clinic located in Ramhormoz County, Khuzestan Province, Iran. Forty participants aged 40 to 50 years were recruited from routine clinical consultations.

Participant recruitment and assessment

Participants aged 40–50 years with no history of ocular disease, surgery, or presbyopic correction were included. Eligibility required a spherical equivalent between −0.50 D and +0.50 D, astigmatism less than -0.50 D, best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better, and IOP within 10–21 mm Hg [17, 18]. The exclusion criteria included systemic medication affecting accommodation or IOP, prior ocular trauma or surgery, and non-compliance with follow-up.

Optical correction of presbyopia was defined as the use of reading glasses by individuals diagnosed with presbyopia, as determined by questionnaire responses and classified into users and non-users.

All participants underwent a full eye examination, including uncorrected and corrected distance visual acuity using the Remote E Chart RL4-6 (Novin Afzar Co., Iran). Objective refraction was measured with an autorefractometer (Topcon RM-A7000, Japan) and verified by dynamic retinoscopy (Keeler, UK). Near vision assessment and presbyopic correction were determined based on accommodative insufficiency, clinical symptoms, and age norms.

IOP was measured by a single examiner using Goldmann applanation tonometry (HAAG-STREIT BERN H03, Switzerland) for consistency. Baseline readings were obtained before optical correction, and follow-up measurements were taken seven days after consistent use of the prescribed near addition [19, 20]. Measurement conditions and timing were standardized to minimize variability.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were calculated for quantitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. A paired t-test was employed to compare IOP before and after presbyopic correction in normally distributed data; otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The McNemar test was applied to evaluate changes in paired categorical variables, such as the proportion of participants with increased versus decreased IOP after correction. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated based on the formula for comparing paired means (before and after intervention) in a cohort study design [21]. Assuming a statistical power of 80%, a significance level (α) of 0.05, and an effect size estimated from previous studies or a pilot study, the final sample size was adjusted to account for a 10% potential dropout rate. The sample size calculation formula used was as follows. Based on this calculation, the minimum required sample size was 33 participants.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

A Total of 50 subjects were initially enrolled in the study. However, 2 participants (4%) were excluded due to a prior history of refractive surgery, which could confound IOP measurements. Additionally, 8 participants (16%) withdrew or were lost to follow-up before the second assessment. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 40 participants, including 18 males (45%) and 22 females (55%), with a mean age of 44.8 years (median 45, range 40–50 years). For statistical consistency and to prevent data duplication, only data from the oculus dexter (OD) right eye were analyzed, assuming symmetry between eyes, consistent with previous literature [21].

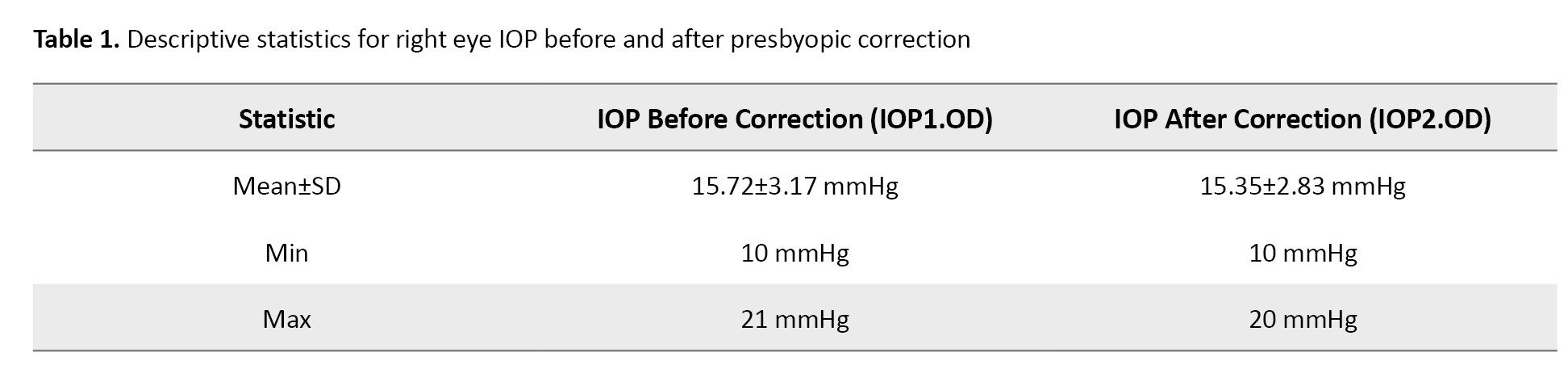

Descriptive analysis of IOP

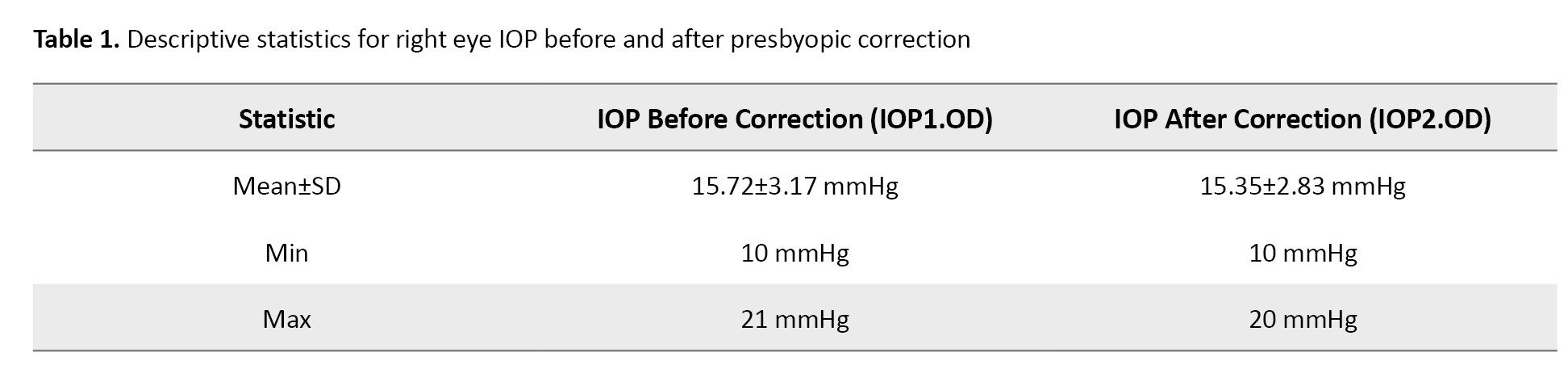

Baseline IOP in the right eye averaged 15.72±3.17 mm Hg before the application of optical correction of presbyopia. After seven days of wearing the correction, the mean IOP slightly decreased to 15.35±2.83 mmHg. The reduction in standard deviation (SD) and the narrowing of the pressure range after correction suggest a modest but consistent lowering effect on IOP across participants (Table 1).

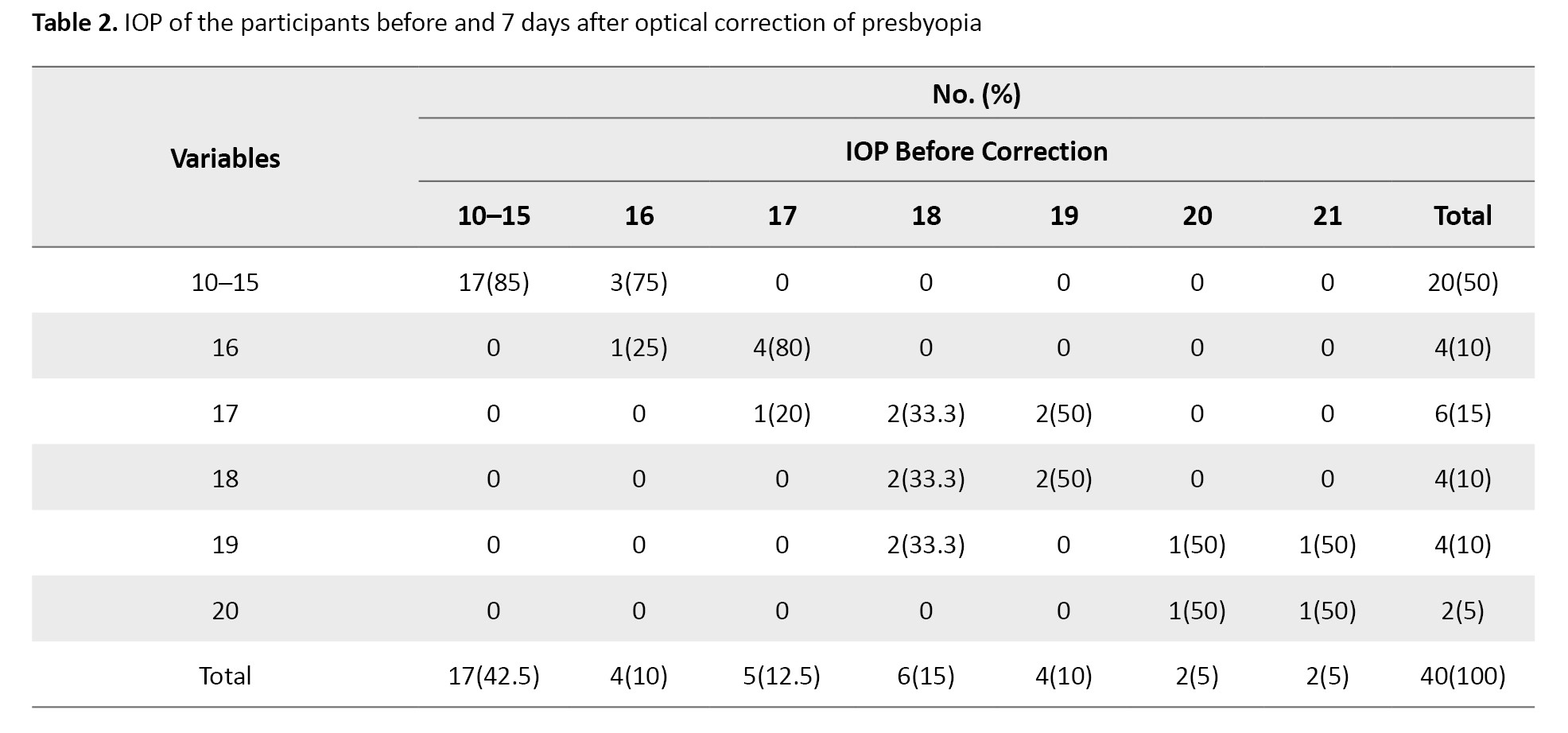

IOP distribution according to initial pressure groups

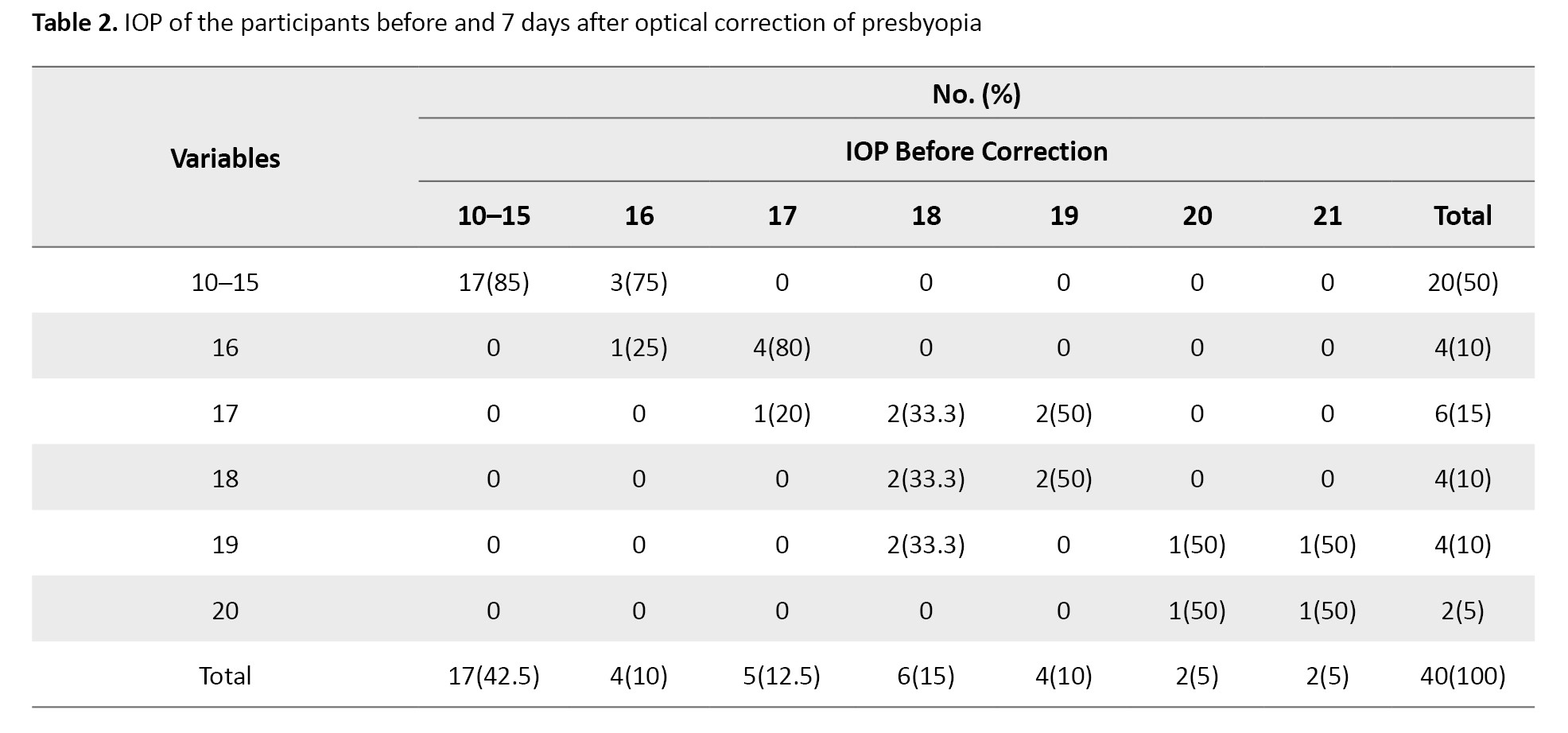

Participants were categorized into 8 groups based on their initial IOP measurements to evaluate whether the degree of pressure change differed according to baseline levels. Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of post-correction IOP values relative to their initial groups.

A significant reduction in the proportion of eyes with IOP≥16 mm Hg was found after correction (P=0.03, the McNemar test). This finding suggests that optical correction of presbyopia may be particularly effective in lowering IOP among participants with higher baseline pressures. The participants were categorized by initial IOP group (McNemar test, P=0.03).

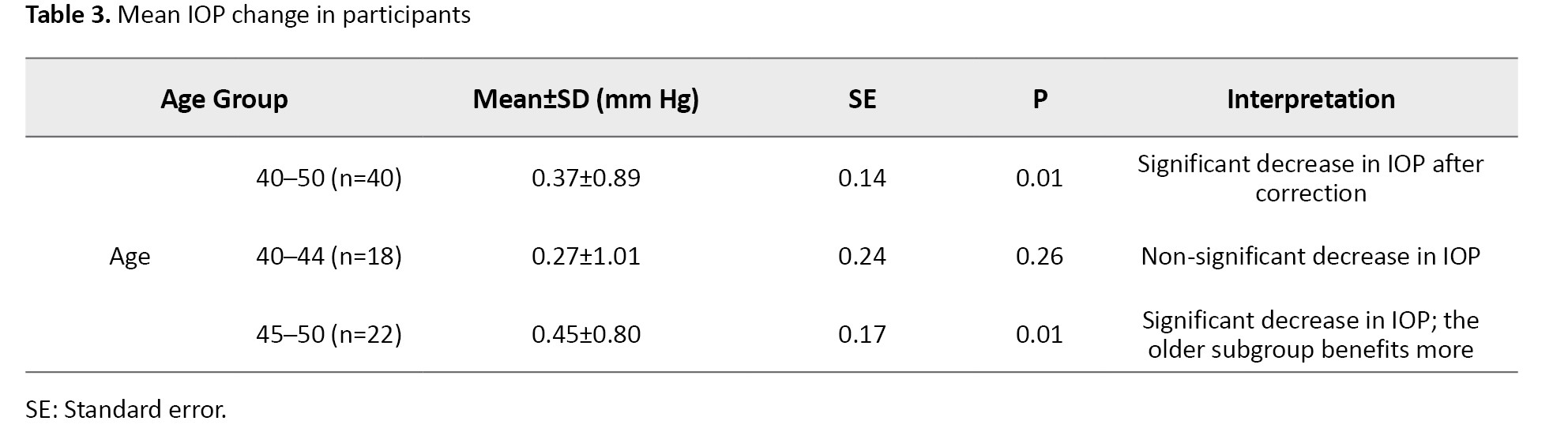

Statistical analysis of IOP changes

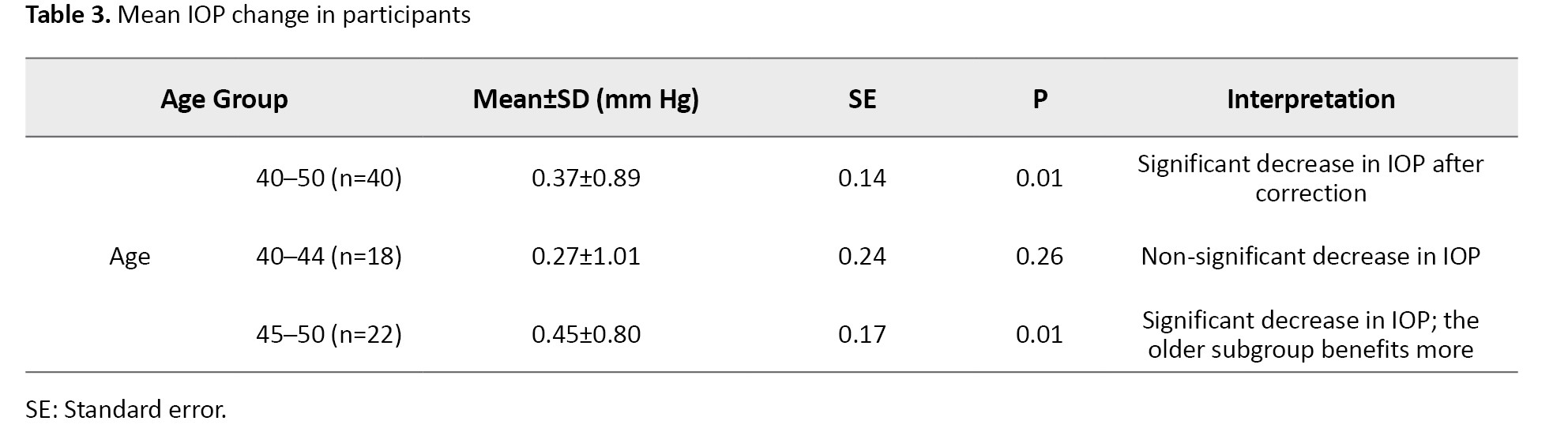

Paired t-test analyses assessed the significance of IOP changes after presbyopic correction across the total sample and age-stratified subgroups (Table 3).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that short-term use of optical correction of presbyopia may influence IOP in adults recently diagnosed with presbyopia. The observed IOP reduction, while modest, reached statistical significance in both the total population and specific subgroups, particularly among older participants and those with baseline pressures suggestive of ocular hypertension [22]. This study addresses a gap in previous research by specifically examining the effect of optical correction of presbyopia on IOP in adults newly entering the presbyopic stage, offering a novel perspective on the relationship between vision correction and ocular physiology. Unlike earlier studies that primarily focused on the impact of active accommodation or near visual tasks on IOP [23, 24], this research is among the first to investigate whether simple near vision correction can induce measurable changes in IOP.

The physiological mechanisms underpinning this effect remain speculative. It is plausible that reducing accommodative strain via optical correction diminishes ciliary muscle contraction and its associated impact on anterior chamber configuration. This outcome, in turn, may facilitate aqueous humor outflow and contribute to a reduction in IOP [25, 26].

The discrepancy in results between the age-stratified subgroups may be attributed to several factors. First, the natural decline in accommodative amplitude and changes in ocular biomechanics differ with advancing age, potentially affecting how presbyopic correction influences IOP. Older individuals may have stiffer crystalline lenses and less flexible ciliary muscles, which could modify the response to optical correction compared to younger presbyopic people [27]. Additionally, age-related variations in aqueous humor dynamics and anterior chamber anatomy might contribute to differential IOP changes [28, 29]. Furthermore, comorbidities that are more prevalent in older adults, such as early glaucomatous changes or vascular alterations, could influence IOP regulation [30]. These physiological and anatomical differences likely explain why the impact of presbyopic correction on IOP varies across age groups.

These findings are especially relevant for individuals on the threshold of ocular hypertension or glaucoma, where even small reductions in IOP can yield significant clinical benefits. Additionally, the data support the notion that accommodative effort, if excessive and sustained without appropriate correction, may contribute to subclinical ocular hypertension in susceptible individuals [31]. Use of optical correction (such as near glasses) may influence ciliary muscle tone and subsequently affect IOP [31]. Recognizing this interaction can aid in the early identification of patients at risk for glaucoma [32]. Considering that IOP may fluctuate following presbyopic correction, ophthalmologists and optometrists can design safer and more personalized prescription protocols, particularly for patients with an elevated risk of glaucoma [33]. Understanding that near vision correction may alter IOP measurements helps optometrists select the most appropriate timing and conditions for accurate pressure assessment, reducing the risk of misdiagnosis or underestimation. Although the effect size was small and may not bear immediate clinical significance in normotensive individuals, the study introduces a valuable paradigm for considering early optical correction of presbyopia as part of comprehensive ocular risk management [34].

The principal limitations of this research include the absence of a control group, a relatively short follow-up period, and a modest sample size. These constraints restrict causal inferences and generalizability. However, the findings align with prior research suggesting a dynamic relationship between visual tasking and ocular pressure [35]. Future studies should adopt longitudinal, randomized designs with larger sample sizes and explore adjunct imaging techniques (e.g. anterior segment OCT) to visualize accommodative structures pre- and post-correction. Examining longer-term IOP changes and their implications for glaucoma risk stratification is also recommended.

Conclusion

Presbyopic optical correction appears to contribute to a short-term decrease in IOP in newly presbyopic adults, particularly among individuals with elevated baseline IOP and those in the upper age bracket of the presbyopic onset range. While further longitudinal studies are required, these results indicate that near correction may serve not only to alleviate visual symptoms but also to influence ocular physiology in significant ways. The integration of accommodative management into broader ocular health strategies could yield preventive benefits, especially for patients at risk of developing ocular hypertension. Clinicians should remain attentive to the systemic effects of visual correction and consider early intervention when appropriate.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1403.536). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study. Participant data were handled confidentially and used solely for research purposes.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Supervision, resources, conceptualization, and project administration: Ali Mirzajani; Writing the original draft, visualization, software, investigation, and data curation: Ariyan Barat; Validation and formal analysis: Jamileh Abolghasemi; Methodology, review, and editing: Ali Mirzajani and Jamileh Abolghasemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and faculty members of the School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for their support during this research. The authors also express their gratitude to all participants for their cooperation and valuable contribution to this study.

References

Presbyopia, a prevalent age-related condition marked by progressive accommodative decline, affects over one billion people globally and is expected to increase substantially as the global median age continues to rise [1]. By 2050, presbyopia will likely constitute a significant public health burden, particularly in middle-aged populations actively engaged in occupational and social activities requiring sustained near vision [2].

Clinically, presbyopia manifests as the eye’s reduced ability to focus on close objects, leading to eye strain, blurred near vision, and difficulty performing daily tasks [3, 4]. The pathophysiology involves decreased elasticity of the crystalline lens, weakening of the ciliary muscles, and altered biomechanical response of the zonular fibers [5]. While the functional impairment is well-documented, its broader implications, including potential changes in intraocular physiology, remain underexplored [6].

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is a central parameter in ocular health maintenance [7]. It is primarily influenced by the dynamic equilibrium between aqueous humor production by the ciliary processes and its outflow through the trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral pathway [8]. Sustained elevation in IOP is a major risk factor for glaucomatous optic neuropathy [9]. Even modest changes in pressure can have implications for individuals predisposed to ocular hypertension [10].

Newly presbyopic individuals, particularly those reluctant to adopt corrective measures, often attempt to overcome near-vision challenges by increasing accommodative effort [11]. This compensatory mechanism can lead to structural and functional changes in the anterior segment, including increased tonus of the ciliary body, narrowing of the anterior chamber angle, and potential interference with aqueous outflow [12, 13]. These anatomical and physiological responses may contribute to transient IOP elevation [14].

In contrast, some literature suggests that tasks involving sustained accommodation, such as reading or near work, may lead to a temporary reduction in IOP, possibly via changes in uveoscleral outflow or muscular tonus modulation [15]. However, results remain inconsistent and context-dependent, highlighting the necessity of focused investigation [16].

This study aims to determine the relationship between initial presbyopic correction and IOP modulation in newly presbyopic adults. By analyzing IOP changes before and after near correction, the research addresses a gap in current understanding. It provides a foundation for future studies in ocular biomechanics and preventive eye care.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This observational, cross-sectional study was performed in 2024 at the Optometry Clinic of Samen Specialty Clinic located in Ramhormoz County, Khuzestan Province, Iran. Forty participants aged 40 to 50 years were recruited from routine clinical consultations.

Participant recruitment and assessment

Participants aged 40–50 years with no history of ocular disease, surgery, or presbyopic correction were included. Eligibility required a spherical equivalent between −0.50 D and +0.50 D, astigmatism less than -0.50 D, best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better, and IOP within 10–21 mm Hg [17, 18]. The exclusion criteria included systemic medication affecting accommodation or IOP, prior ocular trauma or surgery, and non-compliance with follow-up.

Optical correction of presbyopia was defined as the use of reading glasses by individuals diagnosed with presbyopia, as determined by questionnaire responses and classified into users and non-users.

All participants underwent a full eye examination, including uncorrected and corrected distance visual acuity using the Remote E Chart RL4-6 (Novin Afzar Co., Iran). Objective refraction was measured with an autorefractometer (Topcon RM-A7000, Japan) and verified by dynamic retinoscopy (Keeler, UK). Near vision assessment and presbyopic correction were determined based on accommodative insufficiency, clinical symptoms, and age norms.

IOP was measured by a single examiner using Goldmann applanation tonometry (HAAG-STREIT BERN H03, Switzerland) for consistency. Baseline readings were obtained before optical correction, and follow-up measurements were taken seven days after consistent use of the prescribed near addition [19, 20]. Measurement conditions and timing were standardized to minimize variability.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were calculated for quantitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. A paired t-test was employed to compare IOP before and after presbyopic correction in normally distributed data; otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The McNemar test was applied to evaluate changes in paired categorical variables, such as the proportion of participants with increased versus decreased IOP after correction. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated based on the formula for comparing paired means (before and after intervention) in a cohort study design [21]. Assuming a statistical power of 80%, a significance level (α) of 0.05, and an effect size estimated from previous studies or a pilot study, the final sample size was adjusted to account for a 10% potential dropout rate. The sample size calculation formula used was as follows. Based on this calculation, the minimum required sample size was 33 participants.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

A Total of 50 subjects were initially enrolled in the study. However, 2 participants (4%) were excluded due to a prior history of refractive surgery, which could confound IOP measurements. Additionally, 8 participants (16%) withdrew or were lost to follow-up before the second assessment. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 40 participants, including 18 males (45%) and 22 females (55%), with a mean age of 44.8 years (median 45, range 40–50 years). For statistical consistency and to prevent data duplication, only data from the oculus dexter (OD) right eye were analyzed, assuming symmetry between eyes, consistent with previous literature [21].

Descriptive analysis of IOP

Baseline IOP in the right eye averaged 15.72±3.17 mm Hg before the application of optical correction of presbyopia. After seven days of wearing the correction, the mean IOP slightly decreased to 15.35±2.83 mmHg. The reduction in standard deviation (SD) and the narrowing of the pressure range after correction suggest a modest but consistent lowering effect on IOP across participants (Table 1).

IOP distribution according to initial pressure groups

Participants were categorized into 8 groups based on their initial IOP measurements to evaluate whether the degree of pressure change differed according to baseline levels. Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of post-correction IOP values relative to their initial groups.

A significant reduction in the proportion of eyes with IOP≥16 mm Hg was found after correction (P=0.03, the McNemar test). This finding suggests that optical correction of presbyopia may be particularly effective in lowering IOP among participants with higher baseline pressures. The participants were categorized by initial IOP group (McNemar test, P=0.03).

Statistical analysis of IOP changes

Paired t-test analyses assessed the significance of IOP changes after presbyopic correction across the total sample and age-stratified subgroups (Table 3).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that short-term use of optical correction of presbyopia may influence IOP in adults recently diagnosed with presbyopia. The observed IOP reduction, while modest, reached statistical significance in both the total population and specific subgroups, particularly among older participants and those with baseline pressures suggestive of ocular hypertension [22]. This study addresses a gap in previous research by specifically examining the effect of optical correction of presbyopia on IOP in adults newly entering the presbyopic stage, offering a novel perspective on the relationship between vision correction and ocular physiology. Unlike earlier studies that primarily focused on the impact of active accommodation or near visual tasks on IOP [23, 24], this research is among the first to investigate whether simple near vision correction can induce measurable changes in IOP.

The physiological mechanisms underpinning this effect remain speculative. It is plausible that reducing accommodative strain via optical correction diminishes ciliary muscle contraction and its associated impact on anterior chamber configuration. This outcome, in turn, may facilitate aqueous humor outflow and contribute to a reduction in IOP [25, 26].

The discrepancy in results between the age-stratified subgroups may be attributed to several factors. First, the natural decline in accommodative amplitude and changes in ocular biomechanics differ with advancing age, potentially affecting how presbyopic correction influences IOP. Older individuals may have stiffer crystalline lenses and less flexible ciliary muscles, which could modify the response to optical correction compared to younger presbyopic people [27]. Additionally, age-related variations in aqueous humor dynamics and anterior chamber anatomy might contribute to differential IOP changes [28, 29]. Furthermore, comorbidities that are more prevalent in older adults, such as early glaucomatous changes or vascular alterations, could influence IOP regulation [30]. These physiological and anatomical differences likely explain why the impact of presbyopic correction on IOP varies across age groups.

These findings are especially relevant for individuals on the threshold of ocular hypertension or glaucoma, where even small reductions in IOP can yield significant clinical benefits. Additionally, the data support the notion that accommodative effort, if excessive and sustained without appropriate correction, may contribute to subclinical ocular hypertension in susceptible individuals [31]. Use of optical correction (such as near glasses) may influence ciliary muscle tone and subsequently affect IOP [31]. Recognizing this interaction can aid in the early identification of patients at risk for glaucoma [32]. Considering that IOP may fluctuate following presbyopic correction, ophthalmologists and optometrists can design safer and more personalized prescription protocols, particularly for patients with an elevated risk of glaucoma [33]. Understanding that near vision correction may alter IOP measurements helps optometrists select the most appropriate timing and conditions for accurate pressure assessment, reducing the risk of misdiagnosis or underestimation. Although the effect size was small and may not bear immediate clinical significance in normotensive individuals, the study introduces a valuable paradigm for considering early optical correction of presbyopia as part of comprehensive ocular risk management [34].

The principal limitations of this research include the absence of a control group, a relatively short follow-up period, and a modest sample size. These constraints restrict causal inferences and generalizability. However, the findings align with prior research suggesting a dynamic relationship between visual tasking and ocular pressure [35]. Future studies should adopt longitudinal, randomized designs with larger sample sizes and explore adjunct imaging techniques (e.g. anterior segment OCT) to visualize accommodative structures pre- and post-correction. Examining longer-term IOP changes and their implications for glaucoma risk stratification is also recommended.

Conclusion

Presbyopic optical correction appears to contribute to a short-term decrease in IOP in newly presbyopic adults, particularly among individuals with elevated baseline IOP and those in the upper age bracket of the presbyopic onset range. While further longitudinal studies are required, these results indicate that near correction may serve not only to alleviate visual symptoms but also to influence ocular physiology in significant ways. The integration of accommodative management into broader ocular health strategies could yield preventive benefits, especially for patients at risk of developing ocular hypertension. Clinicians should remain attentive to the systemic effects of visual correction and consider early intervention when appropriate.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1403.536). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study. Participant data were handled confidentially and used solely for research purposes.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Supervision, resources, conceptualization, and project administration: Ali Mirzajani; Writing the original draft, visualization, software, investigation, and data curation: Ariyan Barat; Validation and formal analysis: Jamileh Abolghasemi; Methodology, review, and editing: Ali Mirzajani and Jamileh Abolghasemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and faculty members of the School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for their support during this research. The authors also express their gratitude to all participants for their cooperation and valuable contribution to this study.

References

- Sheppard AL, Wolffsohn JS. Digital eye strain: Prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2018; 3(1):e000146. [DOI:10.1136/bmjophth-2018-000146] [PMID]

- Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, Papas E, Burnett A, Ho SM, et al. Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling. Ophthalmology. 2018; 125(10):1492-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.019] [PMID]

- Patel I, West SK. Presbyopia: Prevalence, impact, and interventions. Community Eye Health. 2007; 20(63):40-1. [PMID]

- Chen Y, Wang X, Gao M, Gao R, Song L. The effect of loteprednol suspension eye drops after corneal transplantation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021; 21(1):234. [DOI:10.1186/s12886-021-01982-8]

- Marcos S, Barbero S, Llorente L, et al. Age-related changes in lens biomechanics and their impact on accommodation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022;48(3):381-388. [DOI:10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000451] [PMID]

- Wolffsohn JS, Davies LN. Presbyopia: effectiveness of correction strategies. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019; 68:124-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.09.004]

- Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. Jama. 2014; 311(18):1901-11. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.3192]

- Stamer WD, Acott TS. Current understanding of conventional outflow dysfunction in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012; 23(2):135-43. [DOI:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff23e]

- Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014; 121(11):2081-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013] [PMID]

- Caprioli J, Coleman AL. Intraocular pressure fluctuation a risk factor for visual field progression at low intraocular pressures in the advanced glaucoma intervention study. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115(7):1123-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.031] [PMID]

- Du C, Shen M, Li M, Zhu D, Wang MR, Wang J. Anterior segment biometry during accommodation imaged with ultralong scan depth optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012; 119(12):2479-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.041]

- Ramasubramanian V, Glasser A. Objective measurement of accommodative biometric changes using ultrasound biomicroscopy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015; 41(3):511-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.08.033]

- Ambrosini G, Poletti S, Roberti G, Carnevale C, Manni G, Coco G. Exploring the relationship between accommodation and intraocular pressure: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Graefe's Arch Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2025; 263(1):3-22. [DOI:10.1007/s00417-024-06565-z]

- Yan L, Huibin L, Xuemin L. Accommodation-induced intraocular pressure changes in progressing myopes and emmetropes. Eye. 2014; 28(11):1334-40. [DOI:10.1038/eye.2014.208]

- Priluck AZ, Hoie AB, High RR, Gulati V, Ghate DA. Effect of near work on intraocular pressure in emmetropes. J Ophthalmol. 2020; 2020(1):1352434. [Link]

- Liu J, Roberts CJ. Influence of corneal biomechanical properties on intraocular pressure measurement: Quantitative analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005; 31(1):146-55. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.09.031] [PMID]

- Read SA, Collins MJ, Vincent SJ. Light exposure and eye growth in childhood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56(11):6779-87.[DOI:10.1167/iovs.14-15978] [PMID]

- Lv H, Yang J, Liu Y, Jiang X, Liu Y, Zhang M, et al. Changes of intraocular pressure after cataract surgery in myopic and emmetropic patients. Medicine. 2018; 97(38):e12023. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000012023] [PMID]

- Choy NK, Chiu K, Shum JW, Lai JS. Intraocular Pressure Elevation in the Contralateral Untreated Eye Following Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty in Rabbit Eyes. J Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015; 6:477. [Link]

- Phan R, Bubel K, Fogel J, Brown A, Perry H, Morcos M. Micropulse laser trabeculoplasty and reduction of intraocular pressure: A preliminary study. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2022; 35(2):122-5. [DOI:10.4103/1319-4534.337860] [PMID]

- Albarran-Diego C, Poyales F, López-Artero E, Garzón N, Garcia-Montero M. Interocular biometric parameters comparison measured with swept-source technology. Int Ophthalmol. 2022; 42(1):239-51. [DOI:10.1007/s10792-021-02020-8]

- Ha A, Kim YK, Park YJ, Jeoung JW, Park KH. Intraocular pressure change during reading or writing on smartphone. Plos One. 2018; 13(10):e0206061. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206061]

- Karan S, Baldava S, Afzal R, Fatima F, Begum S, Karan S. The effect of durative computer usage on Intraocular pressure. Int J Life Sci Biotechnol Pharm Res. 2023; 12(4):1. [Link]

- Sheibani N, Zaitoun IS, Wang S, Darjatmoko SR, Suscha A, Song YS, et al. Inhibition of retinal neovascularization by a PEDF-derived nonapeptide in newborn mice subjected to oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2020; 195:108030. [DOI:10.1016/j.exer.2020.108030] [PMID]

- Lee JH, Kim NR. Influence of accommodative relaxation on anterior chamber morphology and IOP. Clin Exp Ophthal mol. 2022;50(3):377-384. [DOI:10.1111/ceo.14054] [PMID]

- Pu Y, Hoshino M, Uesugi K, Yagi N, Wang K, Pierscionek BK. Age-related changes in lens elasticity contribute more to accommodative decline than shape change. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 2025; 66(1):16. [DOI:10.1167/iovs.66.1.16]

- Ameku KA, Pedrigi RM. A biomechanical model for evaluating the performance of accommodative intraocular lenses. J Biomech. 2022; 136:111054. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2022.111054]

- Wang L, Jin G, Ruan X, Gu X, Chen X, Wang W, et al. Changes in crystalline lens parameters during accommodation evaluated using swept source anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Ann Eye Sci. 2022; 7(1):33. [Link]

- Orlov NV, Coletta C, van Asten F, Qian Y, Ding J, AlGhatrif M, et al. Age-related changes of the retinal microvasculature. Plos One. 2019; 14(5):e0215916. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0215916]

- Almarzouki N, Bafail SA, Danish DH, Algethami SR, Shikdar N, Ashram S, et al. The impact of systemic health parameters on intraocular pressure in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022; 14(5):e25217. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.25217]

- Pakravan M, Samaeili A, Esfandiari H, Hassanpour K, Hooshmandi S, Yazdani S, et al. The influence of near vision tasks on intraocular pressure in normal subjects and glaucoma patients.J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2022; 17(4):497. [DOI:10.18502/jovr.v17i4.12350] [PMID]

- Ayaki M, Ichikawa K. Near add power of glaucoma patients with early presbyopia. J Clin Med. 2024; 13(19):5675. [DOI:10.3390/jcm13195675]

- Jarade EF, Nader FC, Tabbara KF. Intraocular pressure measurement after hyperopic and myopic LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2005; 21(4):408-10. [DOI:10.3928/1081-597X-20050701-21]

- Jenssen F, Krohn J. Effects of static accommodation versus repeated accommodation on intraocular pressure. J Glaucom. 2012; 21(1):45-8. [DOI:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31820277a9]

- Dutheil F, Oueslati T, Delamarre L, Castanon J, Maurin C, Chiambaretta F, et al. Myopia and near work: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20(1):875. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20010875] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Optometry

Received: 2025/03/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/11 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2025/03/7 | Accepted: 2025/06/11 | Published: 2025/03/2