Volume 7, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

Func Disabil J 2024, 7(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mazibuko S M, Nadasan T, Govender P. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Rehabilitation Services in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: A Mixed-method Study. Func Disabil J 2024; 7 (1) : 305.1

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-251-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-251-en.html

1- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Berea, South Africa. , senzelwe@icloud.com

2- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Berea, South Africa.

2- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Berea, South Africa.

Keywords: Infrastructure, Referral pathways, Human resources, Multidisciplinary practice, Rehabilitation services, South Africa

Full-Text [PDF 857 kb]

(487 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1109 Views)

Full-Text: (340 Views)

Introduction

Despite South Africa being a signatory to the national rehabilitation policy [1] and the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities [2], access to rehabilitation services remains a challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings [3-8]. Specifically, in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Province, South Africa, patients face difficulties in accessing rehabilitation services due to limited infrastructure, disjointed referral pathways, lack of patient involvement, transport costs, shortage of rehabilitation service disciplines, and geographically inaccessible institutions [5, 8]. The public health system’s capacity to provide rehabilitation services in KZN is limited and does not adequately address the population’s needs [5, 8, 9].

As healthcare services improve and the population lives longer, non-communicable diseases, such as stroke, diabetes, and cerebrospinal conditions are increasing [8, 10, 11]. However, these conditions are not being diagnosed at admission, and there is a lack of standardized rehabilitation service treatment plans [8, 12]. Providing appropriate rehabilitation services requires a multidisciplinary approach involving various healthcare professionals, namely physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, speech therapists, audiologists and nutritionists [4, 6, 13-19]. However, rehabilitation service teams in South Africa are imbalanced and incomplete due to a lack of funding for personnel [5, 13, 15-18].

Moreover, rehabilitation services infrastructure in the form of designated rehabilitation service units at district hospitals is almost non-existent [3-6, 9]. Such designated rehabilitation service units can be described as intermediate care facilities that restore the functional status of rehabilitation service patients through a multidisciplinary practice at lower-intensity care than an acute institution [20].

There is also a lack of informative research on indicators for appropriate rehabilitation services development, and no standard operating procedure guides the provision of rehabilitation services in KZN [9]. Referral pathways are irregular, leading to inadequate follow-up and avoidable complications for clients [3-6, 9]. Additionally, the field of rehabilitation services lacks innovation, with human resources being paper-driven and lacking preparedness for the fourth industrial revolution [21]. The South African government faces resource challenges in improving the healthcare system, including fiscal shortages, constrained innovation, stagnant technological advancement, and poor human resources for healthcare [20, 22, 23]. As a result, the increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases in rural areas puts pressure on the rehabilitation services system [3-6].

Biomedical practitioners at the clinical level focus on patient stabilization and are inappropriately aware of rehabilitation services [3-6]. As such, rehabilitation services data-capturing is nebulous and not meaningful. Rehabilitation service patients rely on traditional clinical practice that considers rehabilitation services as being separate from clinical care [3-6, 9]. Rehabilitation services patients are referred later than advisable for recovery. Due to chronic shortages of rehabilitation staff, services are usually in urban areas, far from the patient’s admission hospital. Rehabilitation service referral pathways lack a case-based system to categorize patients with similar clinical diagnoses to control costs (diagnosis-related groupers). This issue results in high costs for transport and long waiting times for sessions, resulting in fatigue and patients being lost in the system of the continuum of care [24].

In the South African government’s quest to re-engineer primary healthcare [25, 26], rehabilitation services have been identified as an integral feature of a transformed public health system [9]. As a result, scientific evidence is essential to inform South Africa’s Department of Health (DoH) in its quest. Therefore, this study was conducted to profile the status of rehabilitation service provision in South Africa regarding infrastructure, referral pathways, human resource practices, and multidisciplinary practices in KZN Province.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study utilized the viable system model (VSM) as its theoretical framework to analyze rehabilitation infrastructure, referrals, and multidisciplinary practices in KZN. VSM, a systems theory, emphasizes the importance of external regulation for organizational success. The study employed a concurrent mixed-methods design, combining qualitative (focus group discussions) and quantitative (cross-sectional survey) approaches. This design aimed to comprehensively describe current rehabilitation practices in KZN, focusing on infrastructure, referral pathways, human resources, and multidisciplinary practices.

Study population and sample description

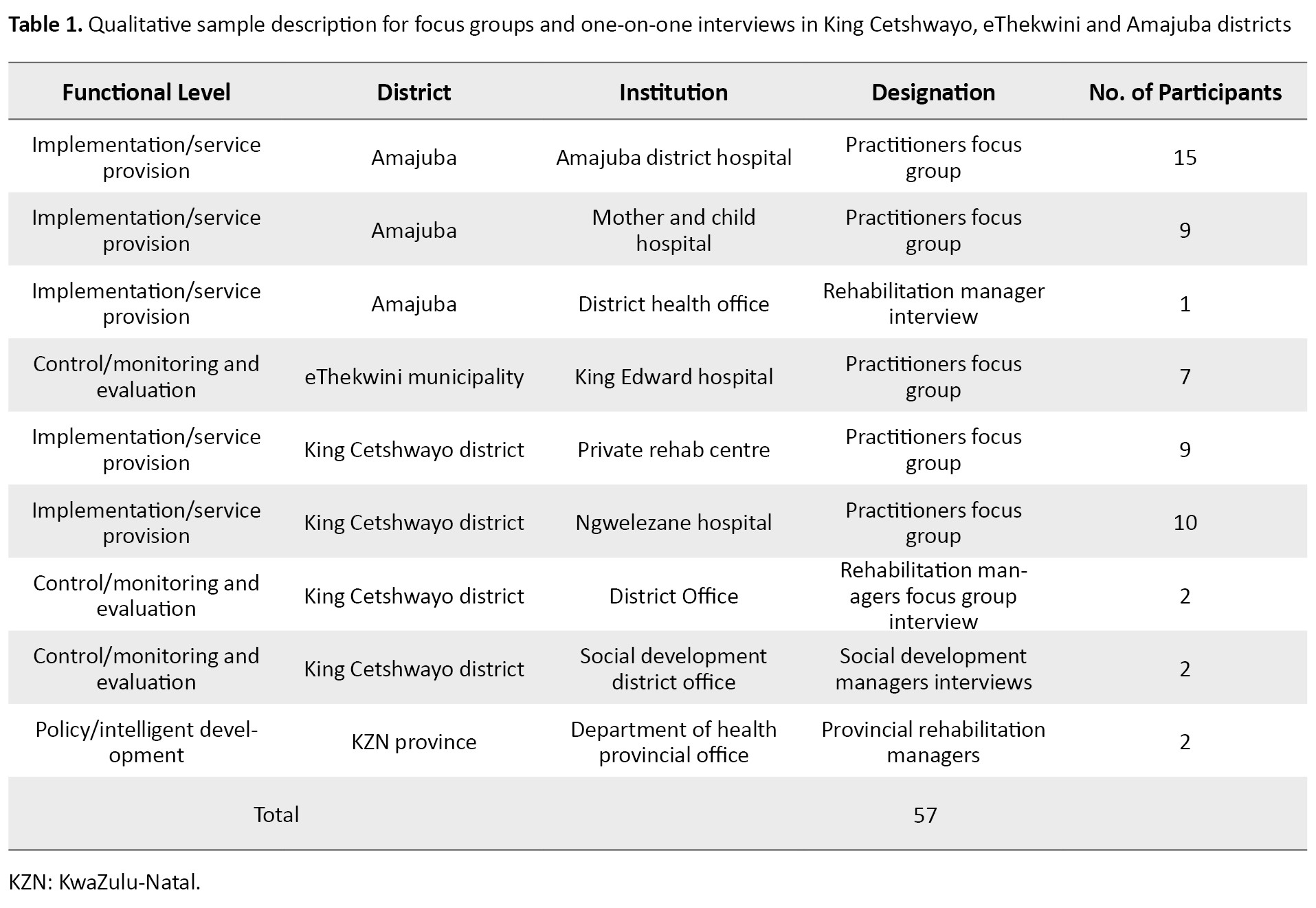

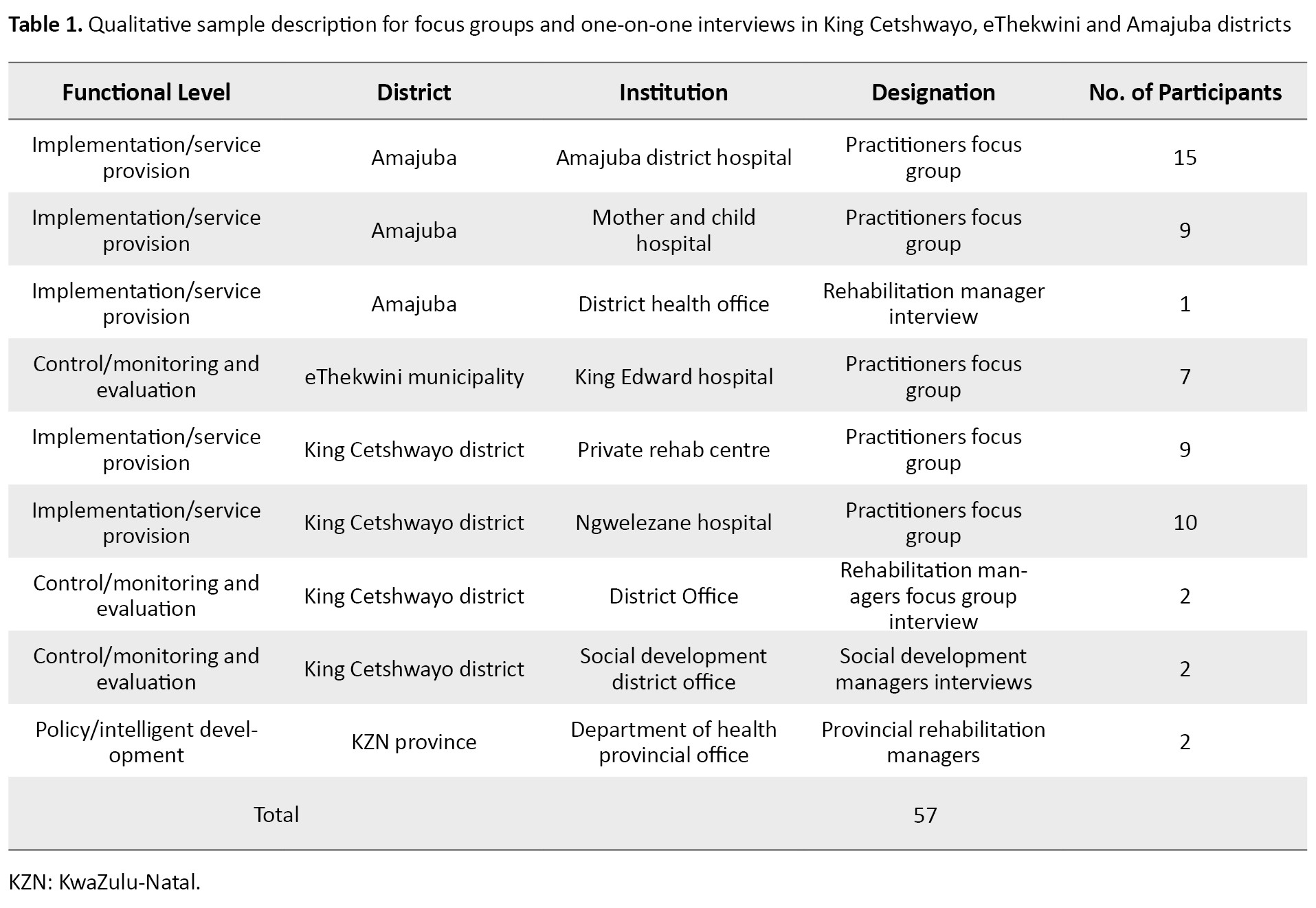

The population included rehabilitation practitioners, district rehabilitation services managers, and policymakers from Amajuba District Municipality, King Cetshwayo District Municipality and the eThekwini Metropolis in KZN. Non-probability stratified and maximum variation purposive sampling were employed to recruit 99 participants. The qualitative component involved 57 participants, including practitioners, managers, and representatives from relevant departments. The quantitative component sampled 42 practitioners using the snowball method, representing different districts (Table 1).

Data collection

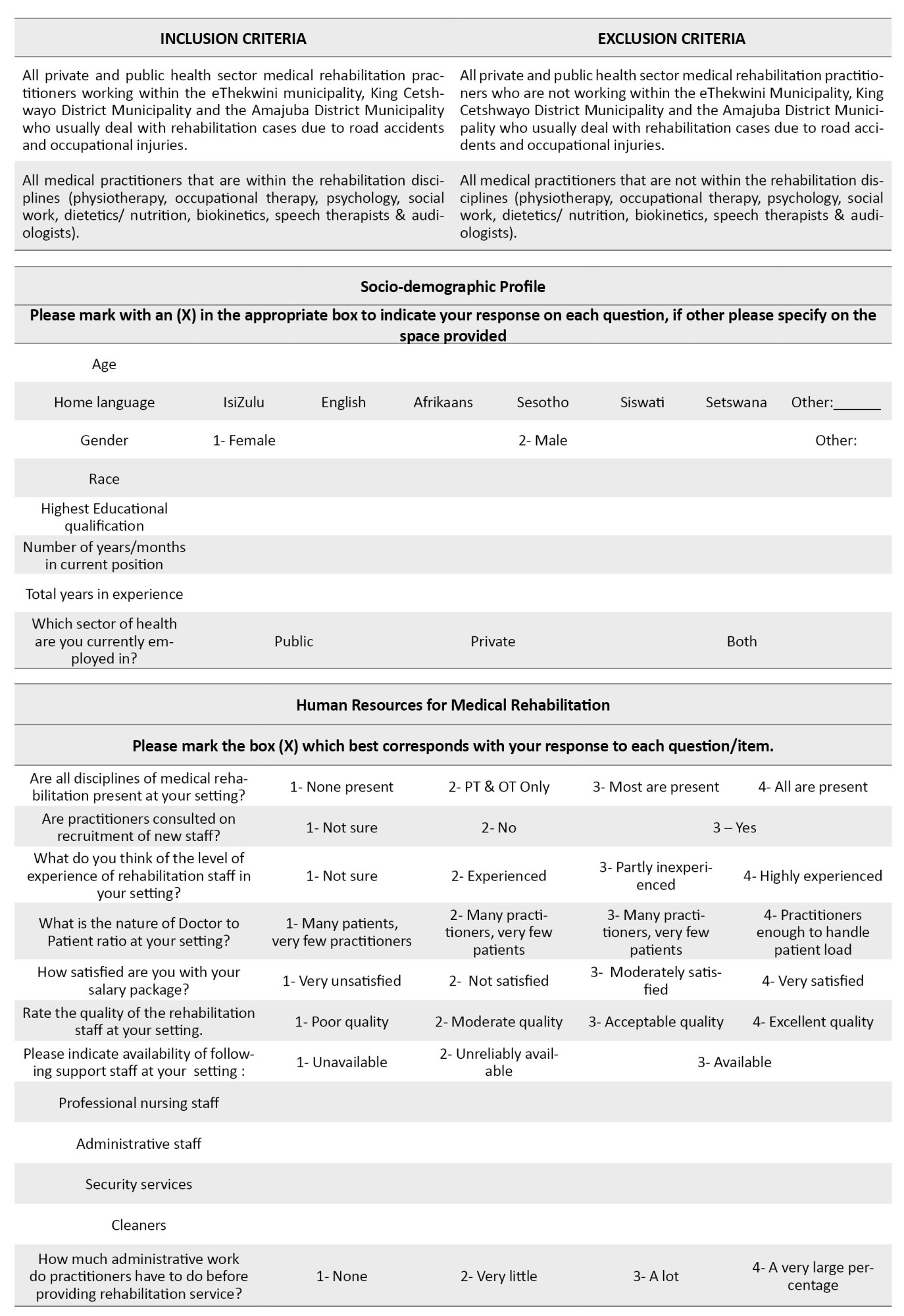

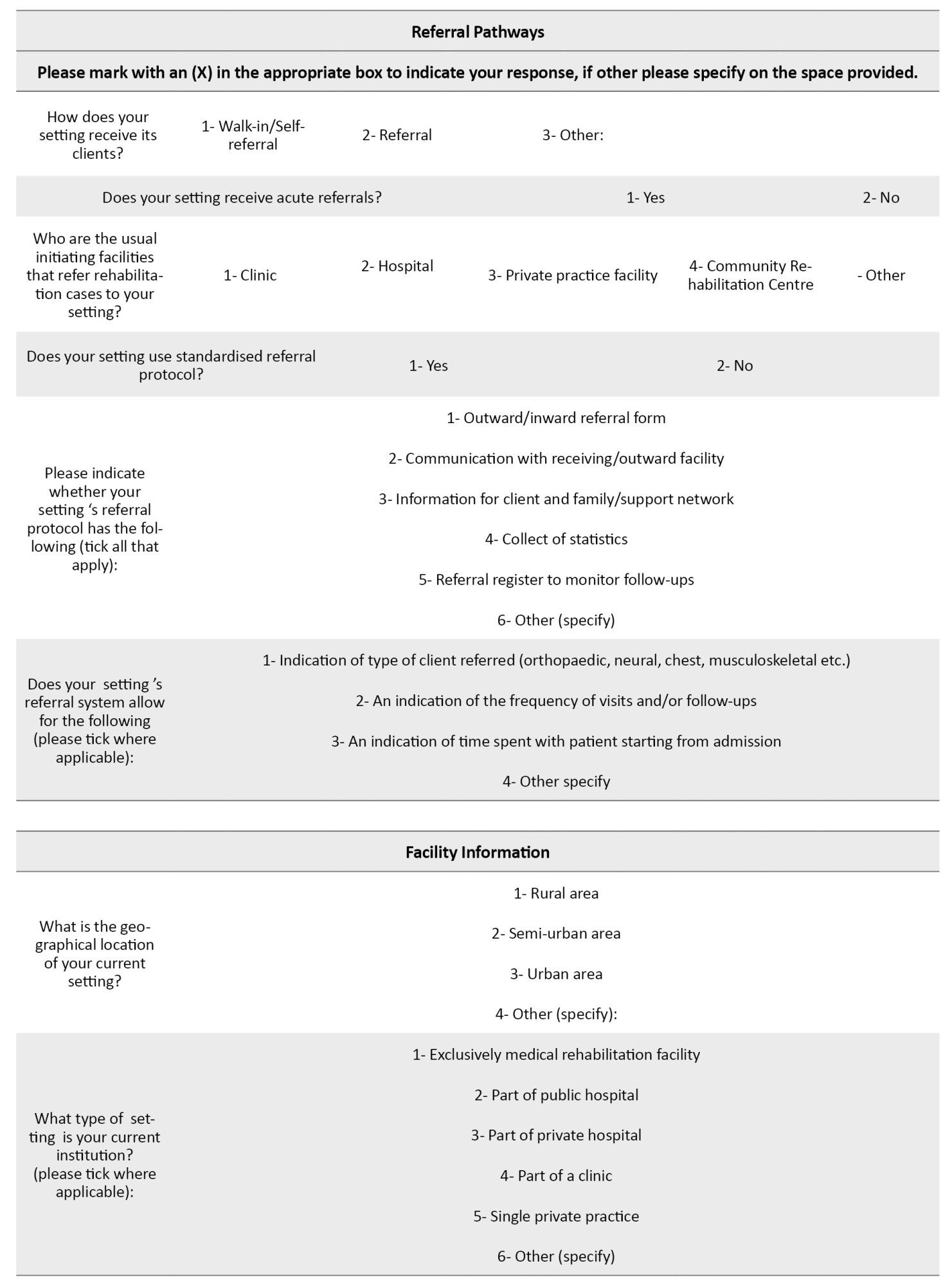

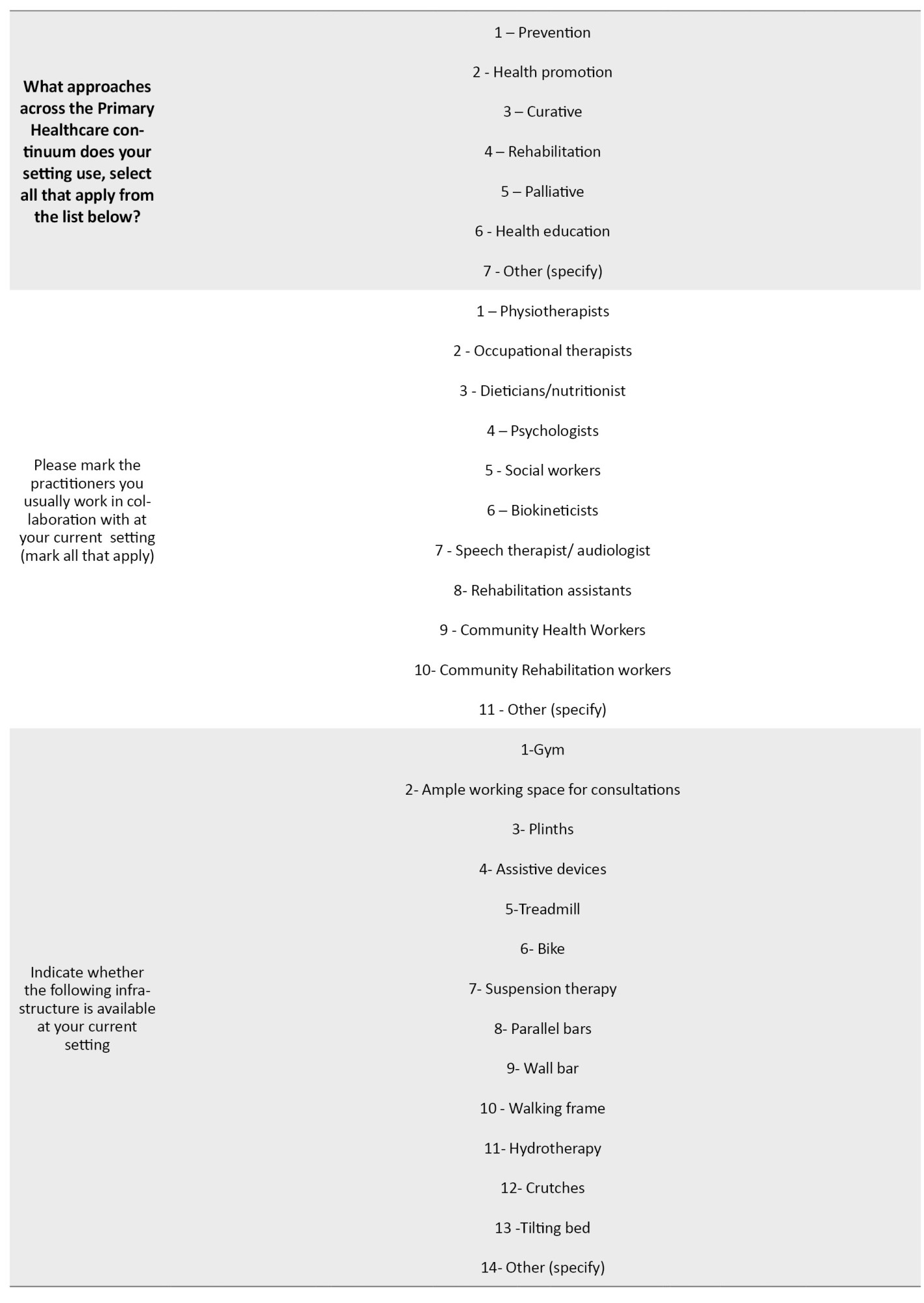

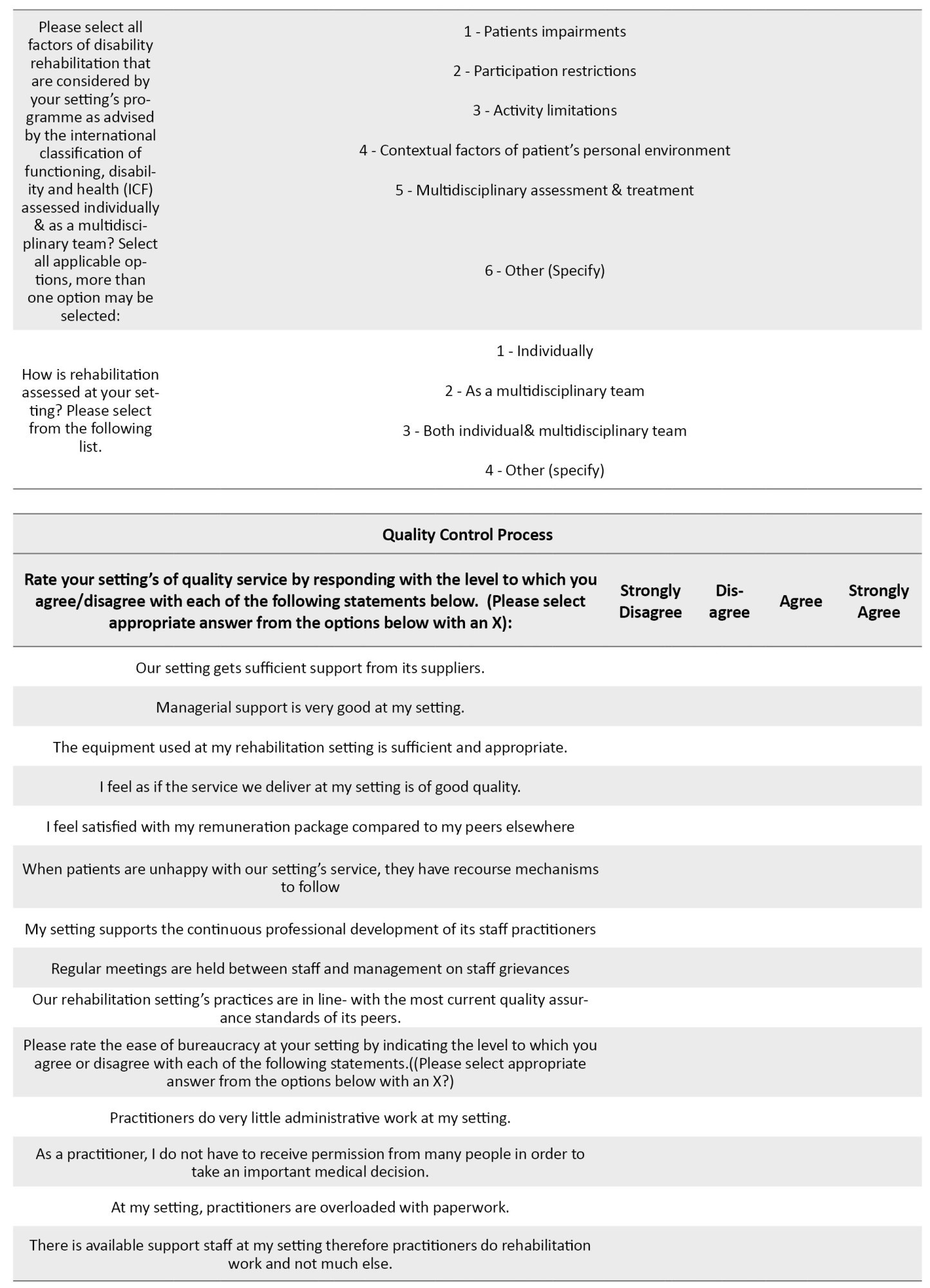

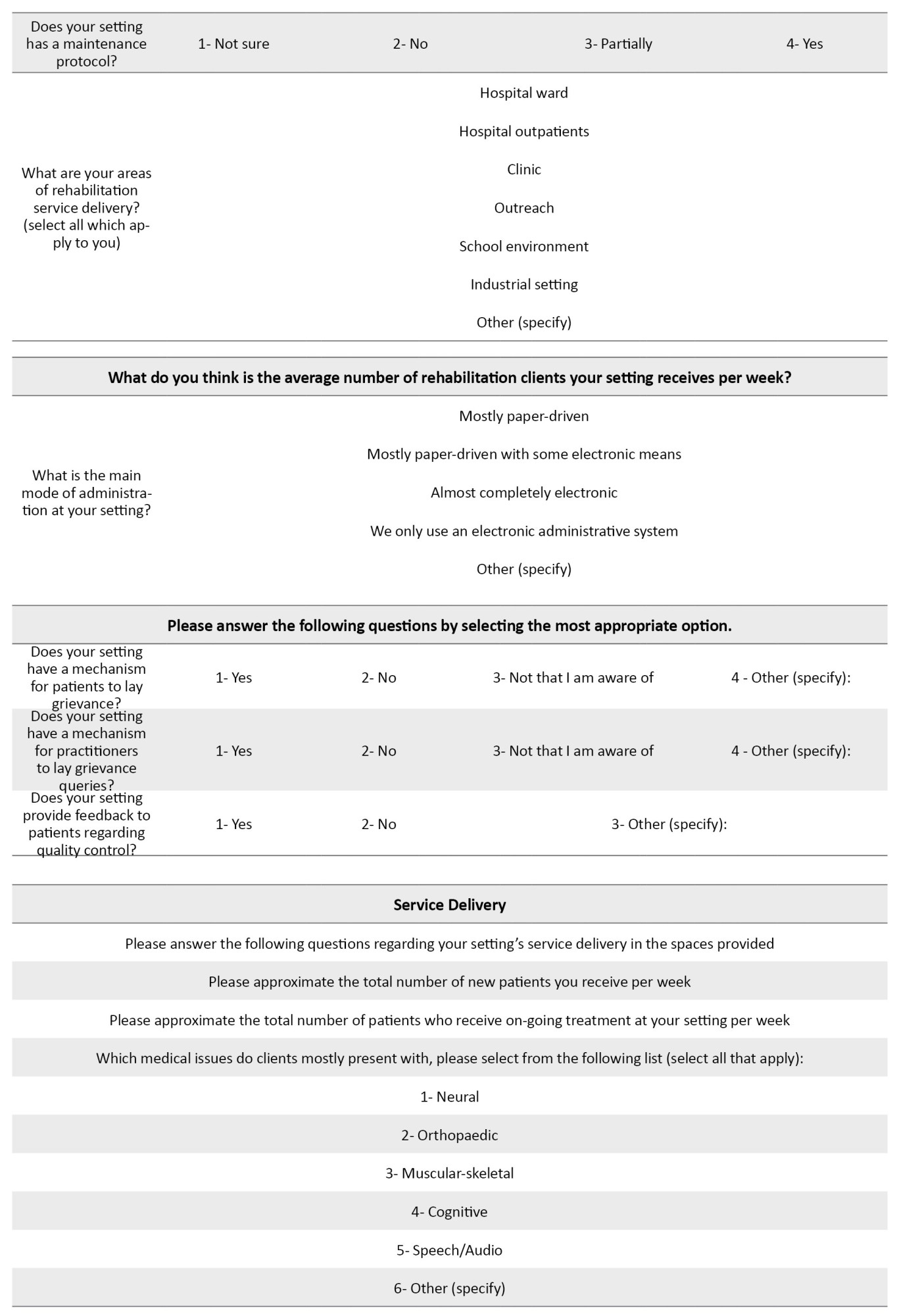

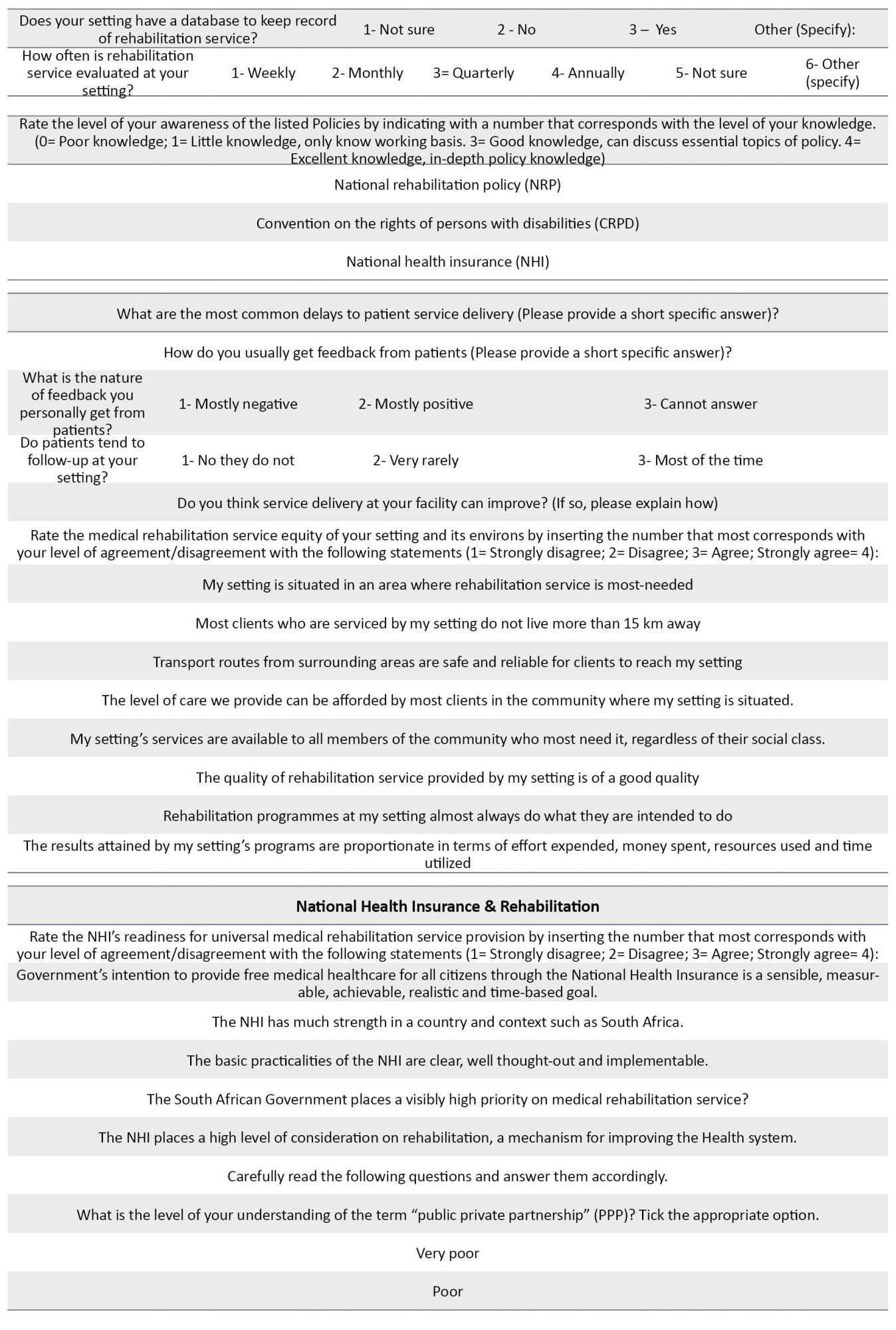

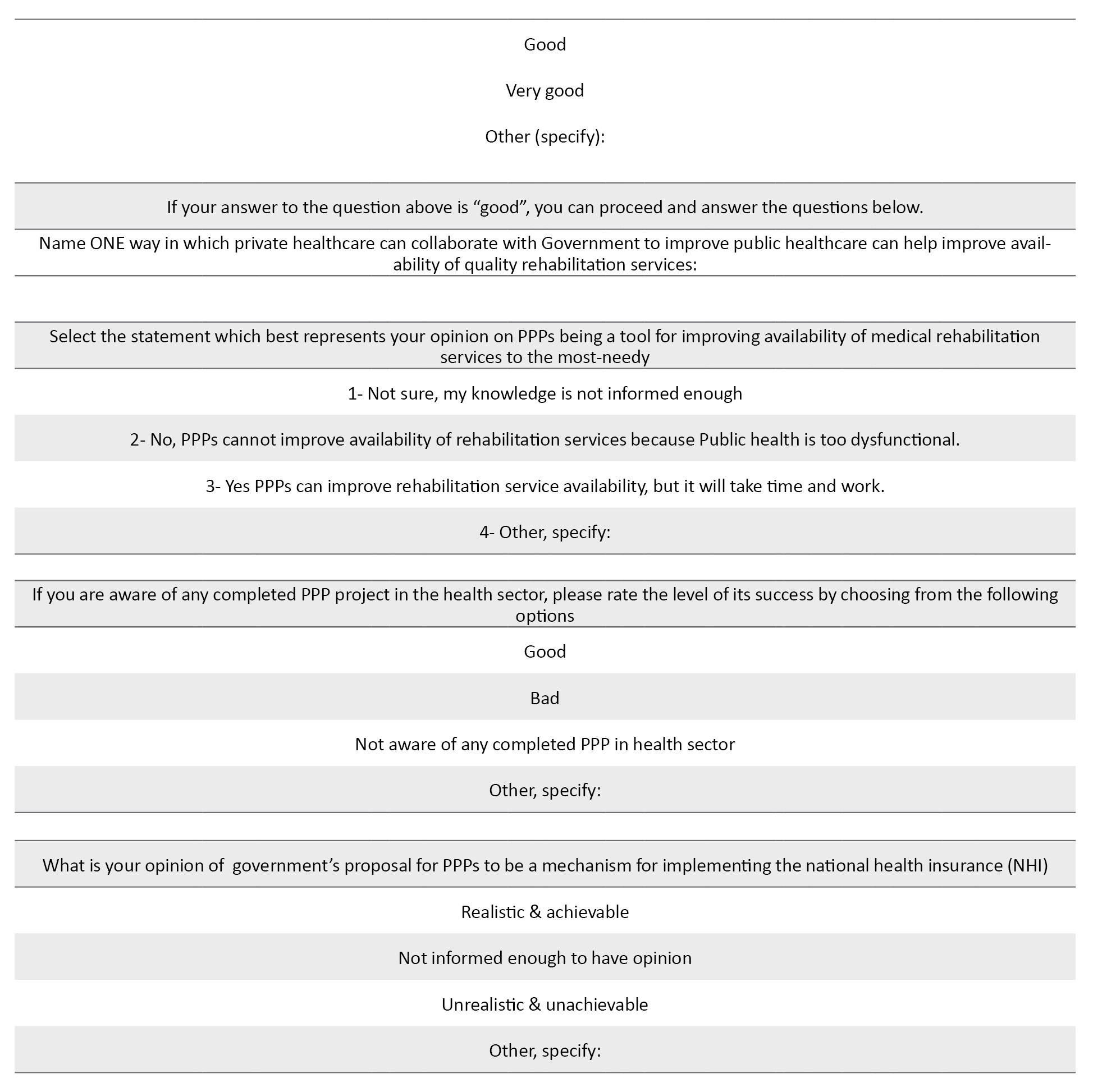

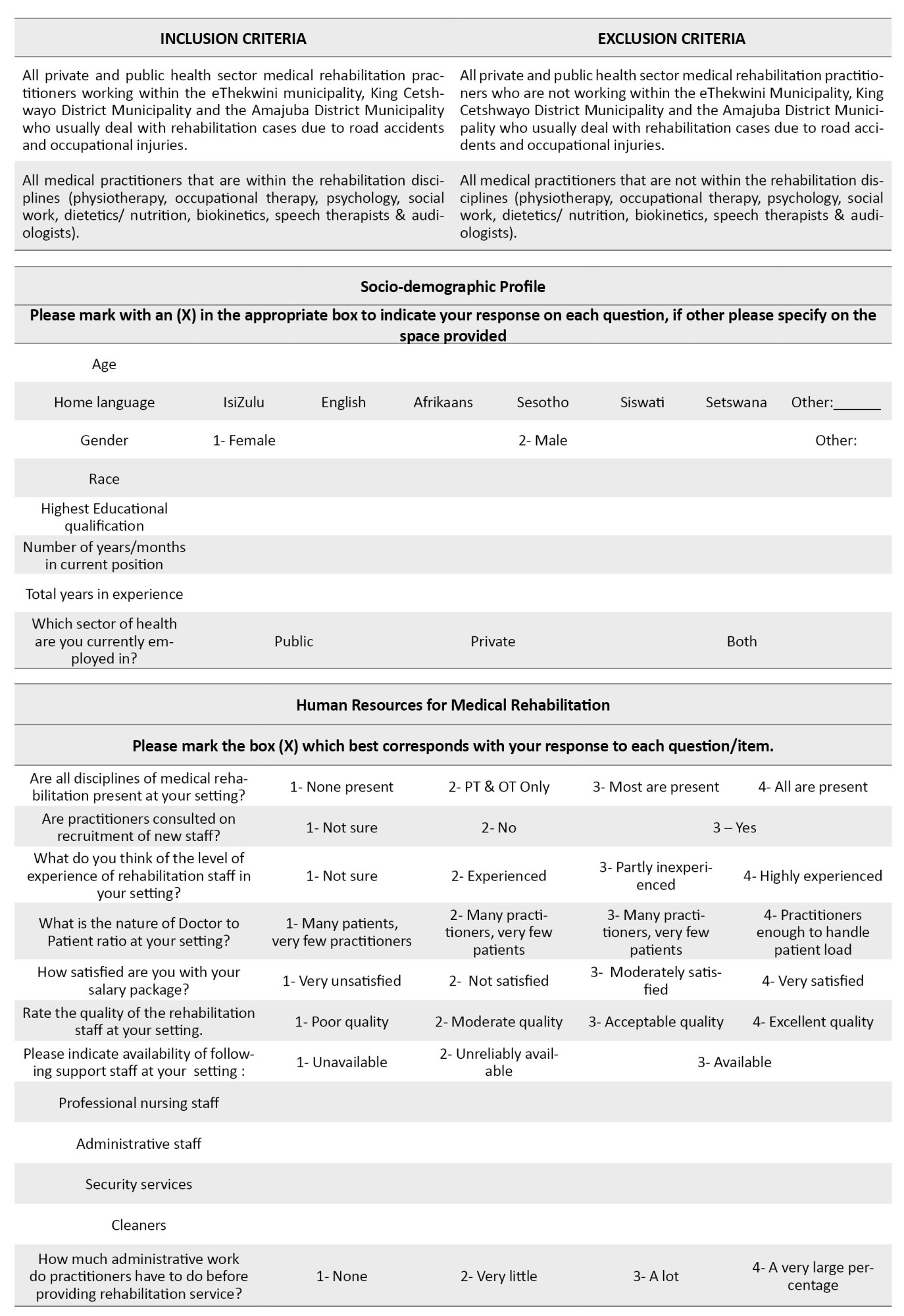

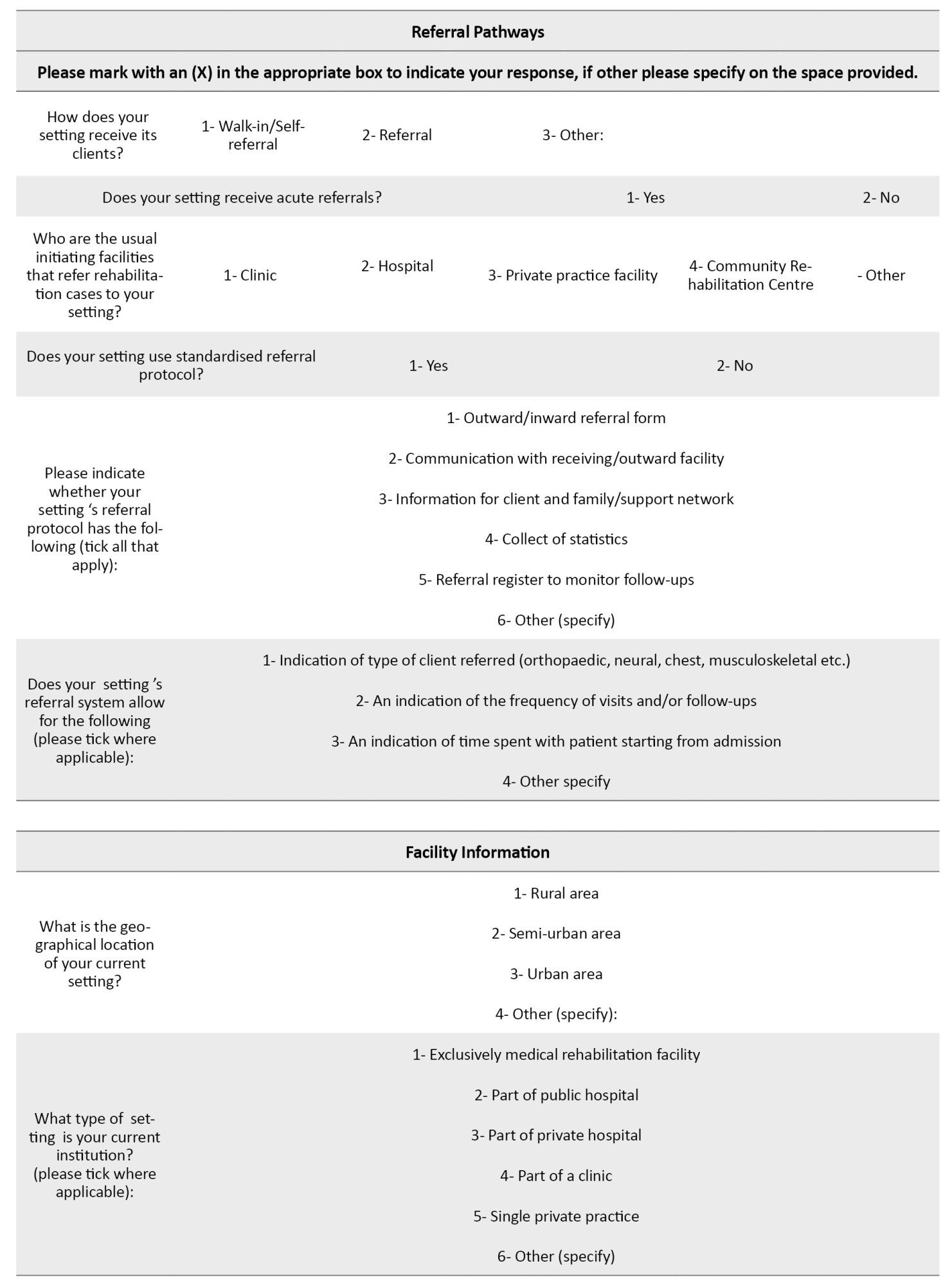

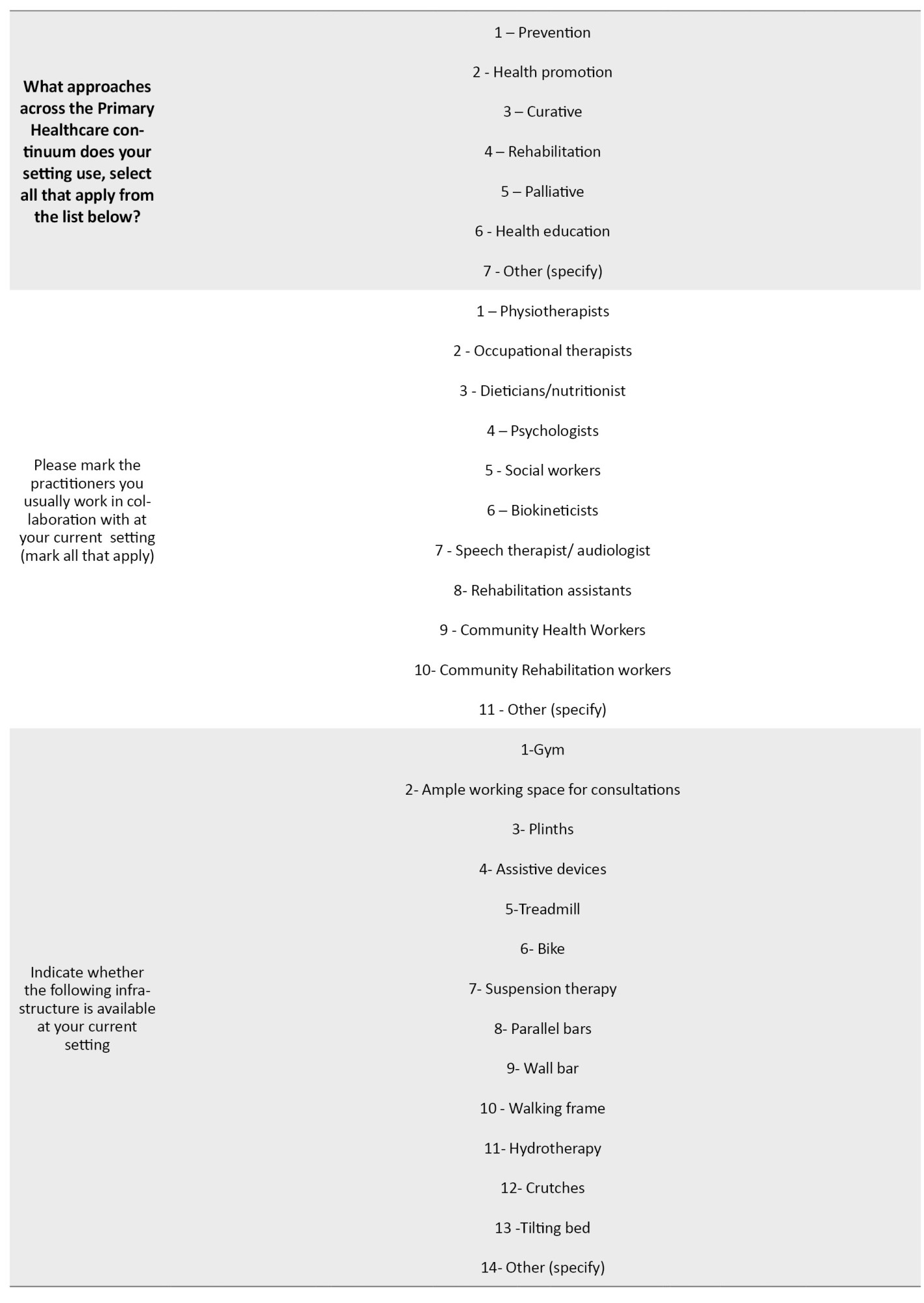

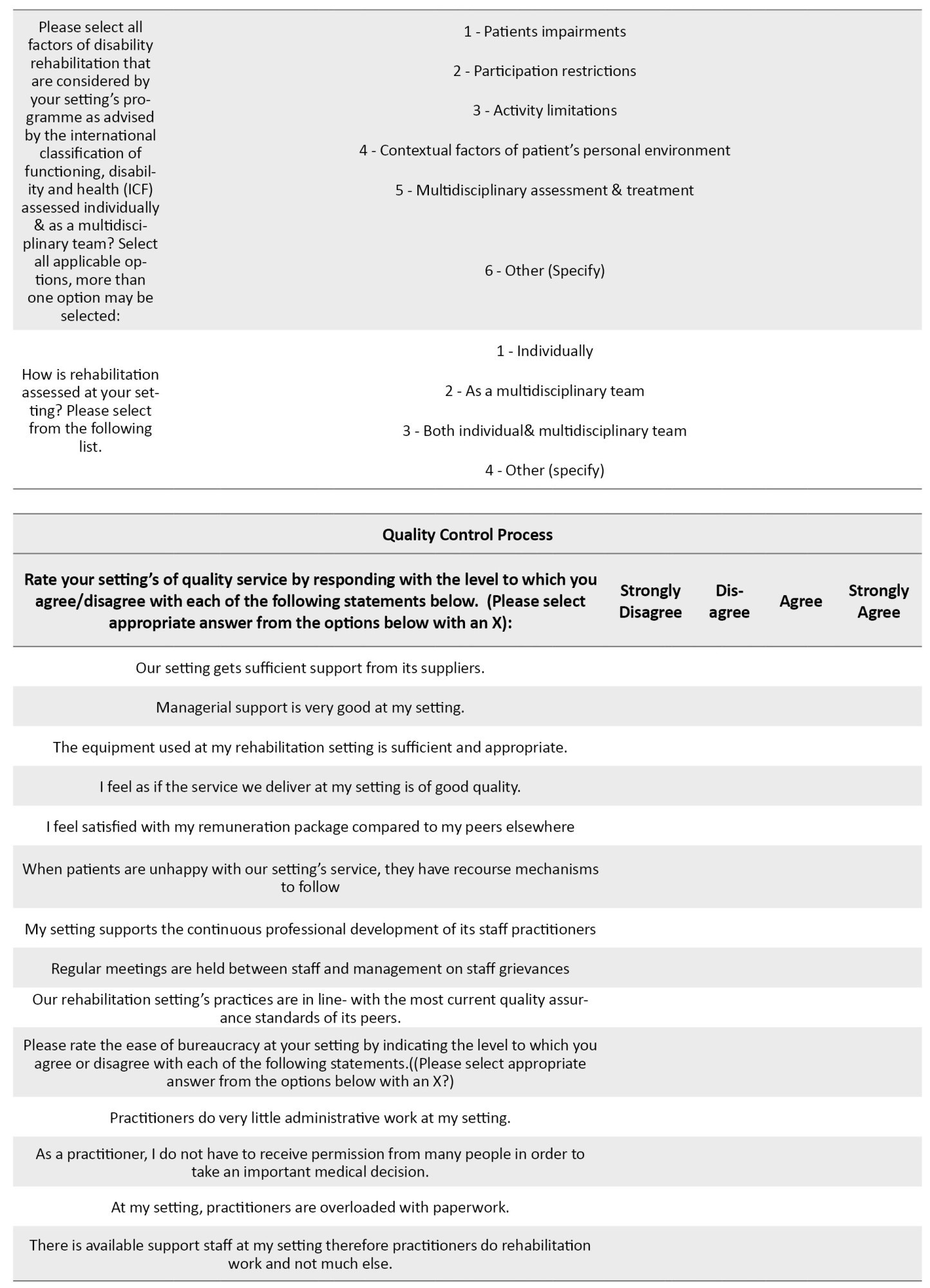

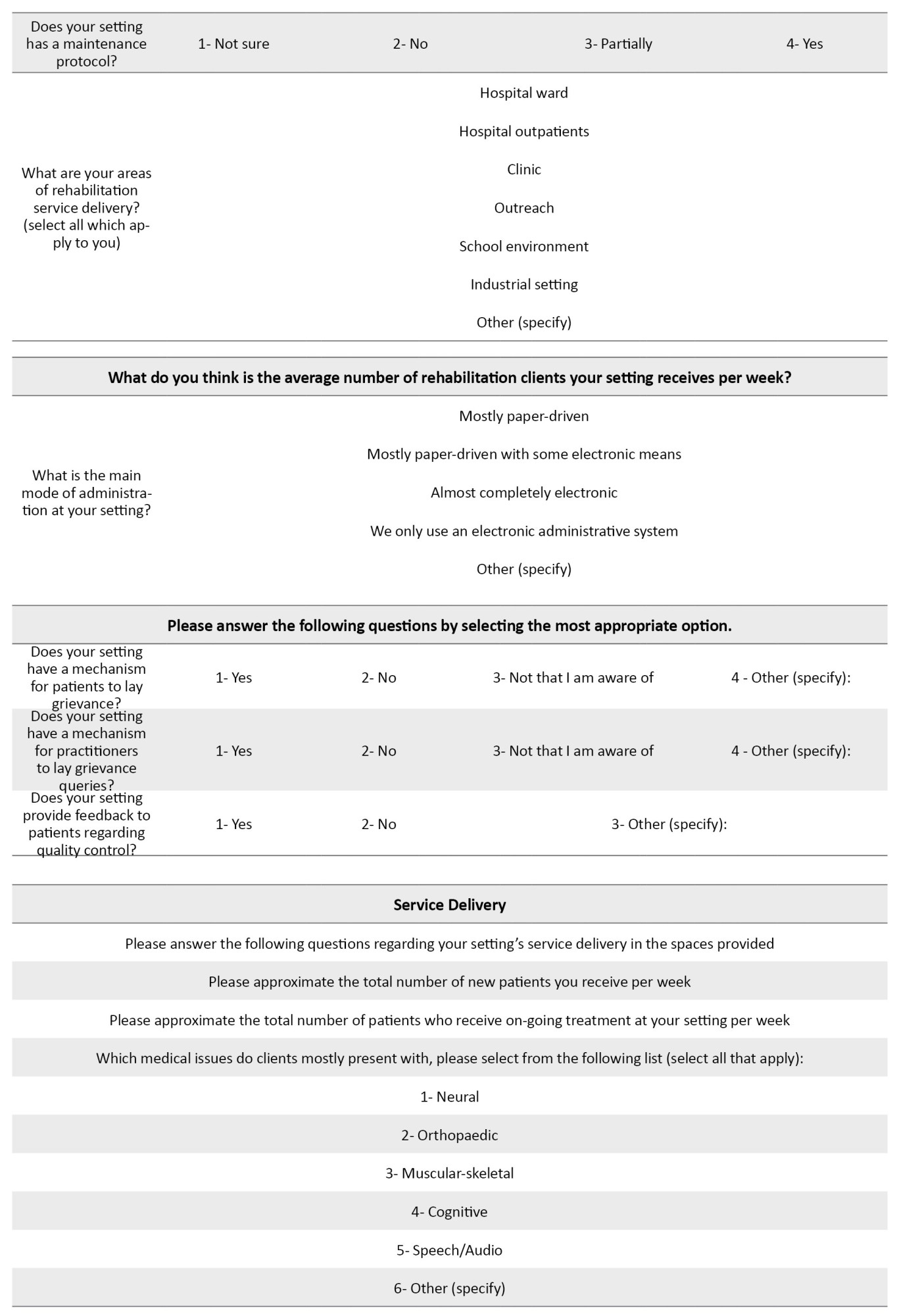

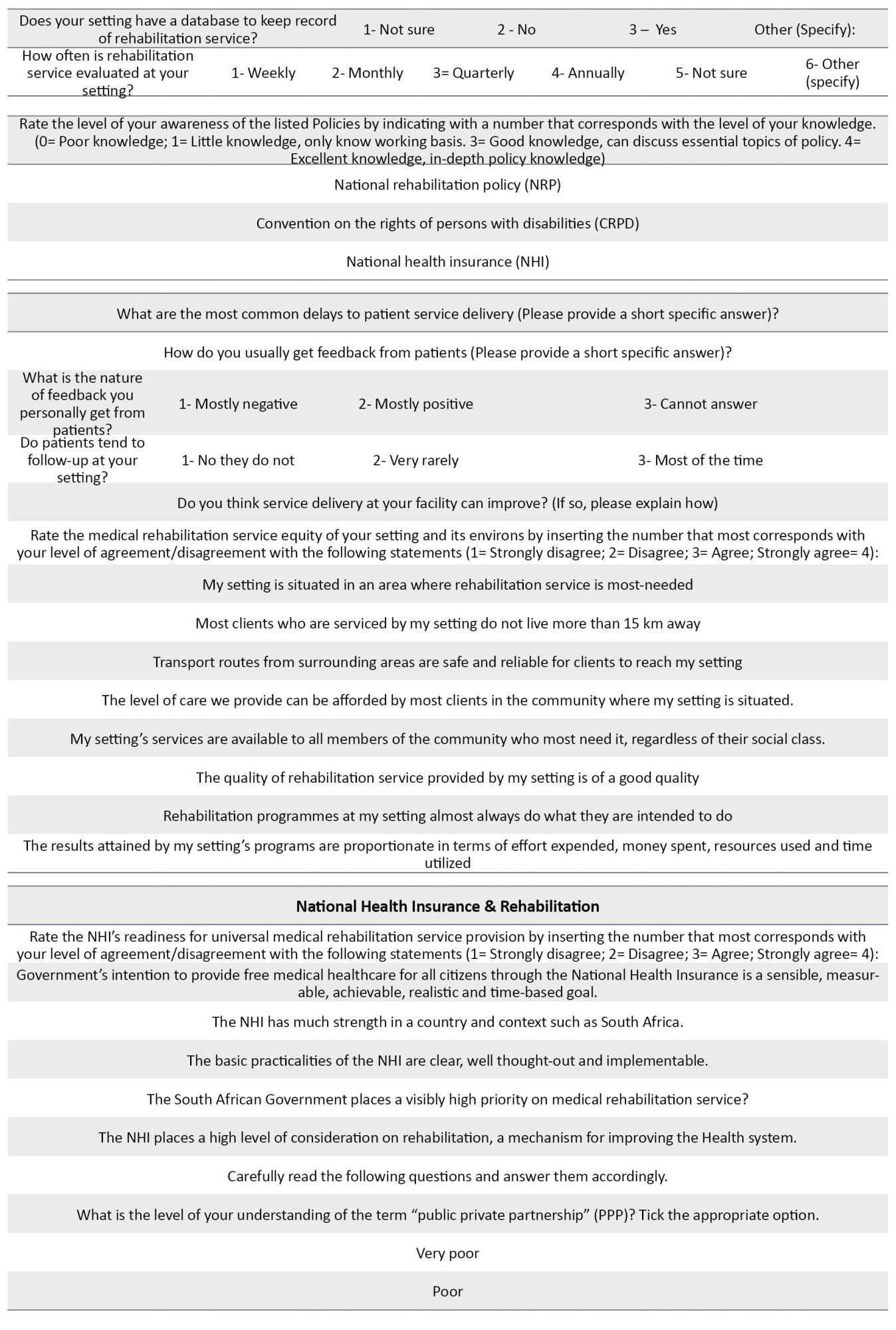

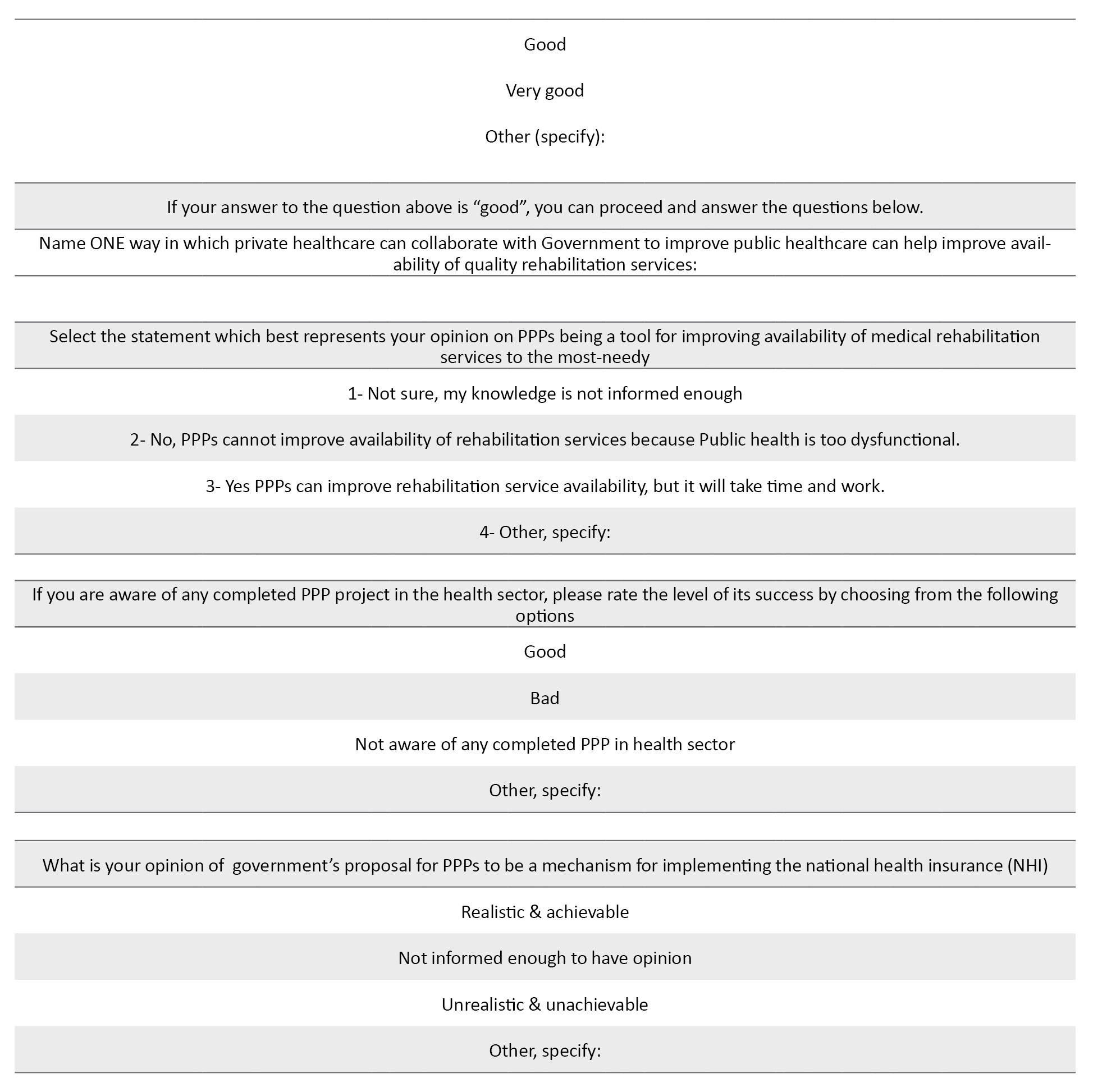

Data collection commenced after the COVID-19 period, with quantitative surveys distributed before qualitative focus groups. Separate interviews were conducted for managers and practitioners. Interview schedules were designed collaboratively and piloted for refinement. Data collection involved one-to-one interviews, focus groups, and surveys conducted over two months. For the qualitative data collection, interview schedules were designed to profile data specific to different districts and focused on the current status and practices of rehabilitation services. Trustworthiness was ensured through the researcher’s extensive experience and the use of actual quotes from participants. Interviews were between 30 and 60 minutes. Two one-to-one interviews were conducted with social development representatives from the King Cetshwayo District. Two focus groups were conducted by the researcher with rehabilitation service practitioners from the Amajuba District Municipality and the King Cetshwayo District Municipality. Three focus groups were conducted by the researcher with rehabilitation services practitioners in the eThekwini Metro and the King Cetshwayo District Municipality. One focus group was held with 2 provincial health representatives. The duration of the focus groups was between 30 to 40 minutes. Regarding quantitative data collection, a survey tool designed by the researcher and supervisors, aimed to enhance qualitative data. It consisted of six sections covering demographic profiles, rehabilitation practice, referral pathways, facility information, quality control processes, and service delivery. Likert scales and closed-ended multiple-choice items were utilized (Appendix A).

Appendix A: Data collection tool

Introduction

Dear participant. You have been invited to be a part of this Doctoral research study because you are a medical rehabilitation practitioner in the King Cetshwayo District, Amajuba District, or the eThekwini Municipality District. This survey is a part of the study’s data collection. The study aims to create a model for the provision of medical rehabilitation services that are timeous, equitable, multidisciplinary and accessible to as many clients at the district and local level of care.

Your participation in this field research will provide quantitative expert opinion on medical rehabilitation from those who provide it on a daily basis. This survey will be used for data on the status of rehabilitation, equitable access to medical rehabilitation, multidisciplinary practice and the national health insurance’s consideration of medical rehabilitation. This survey will gather information on socio-demographics, human resources for medical rehabilitation, referral pathways, rehabilitation facility information, quality control processes and service delivery. The subjective, personal and qualitative experiences gained from this interview will inform the researcher construct a model for District-based medical rehabilitation care.

Objectives

To conduct a scoping review of PPP usage for rehabilitation service delivery in KZN.

Establish referral pathway practices for rehabilitation service, to establish current human resource practices for rehabilitation, and to establish current access to rehabilitation services in KZN.

Improve human resources for rehabilitation by re-engineering multidisciplinary practice in KZN. Improve access to rehabilitation infrastructure through the intermediate care approach at the district health system.

Ascertain and forecast cost risks to rehabilitation services from RAF and COIDA case managers and compensation office representative respectively.

Review level to which rehabilitation is considered by NHI Bill with participants. Assess participants’ views on operational mechanisms of universally covered rehabilitation services.

Solicit expertise and the experiences of rehabilitation practitioners, managers, NGOs and patients respectively to develop model of rehabilitation service provision in KZN.

To identify strategies for stakeholder uptake and potential threats to the implementation of the model.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes [27]. Quantitative data were captured using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using IBM SPSS software, version 24. The study ensured confirmability and dependability through an audit trail and the reflexivity of the researcher. Credibility was enhanced through data triangulation and thick description, ensuring the transferability of findings through consideration of context and participant experiences.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

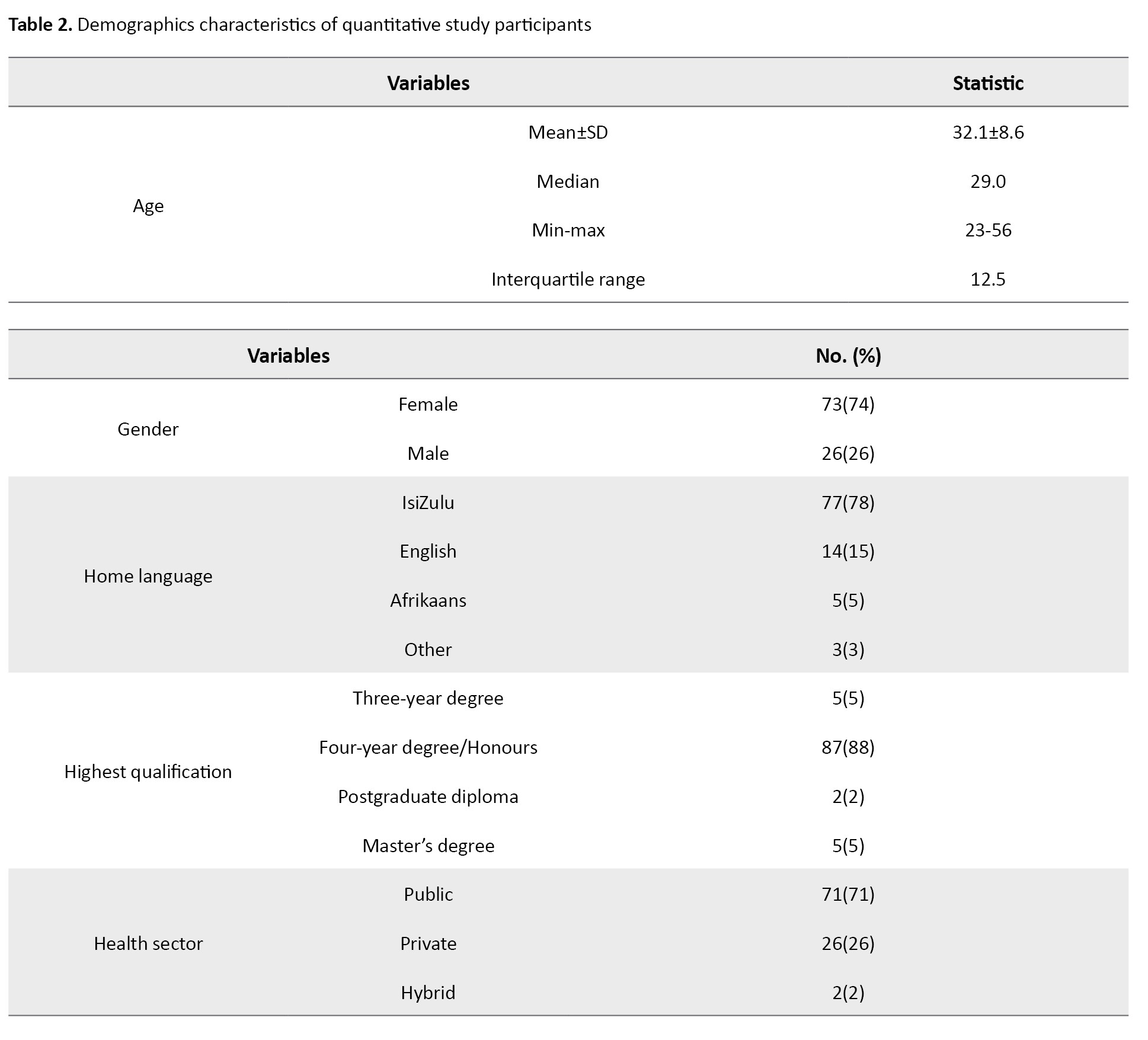

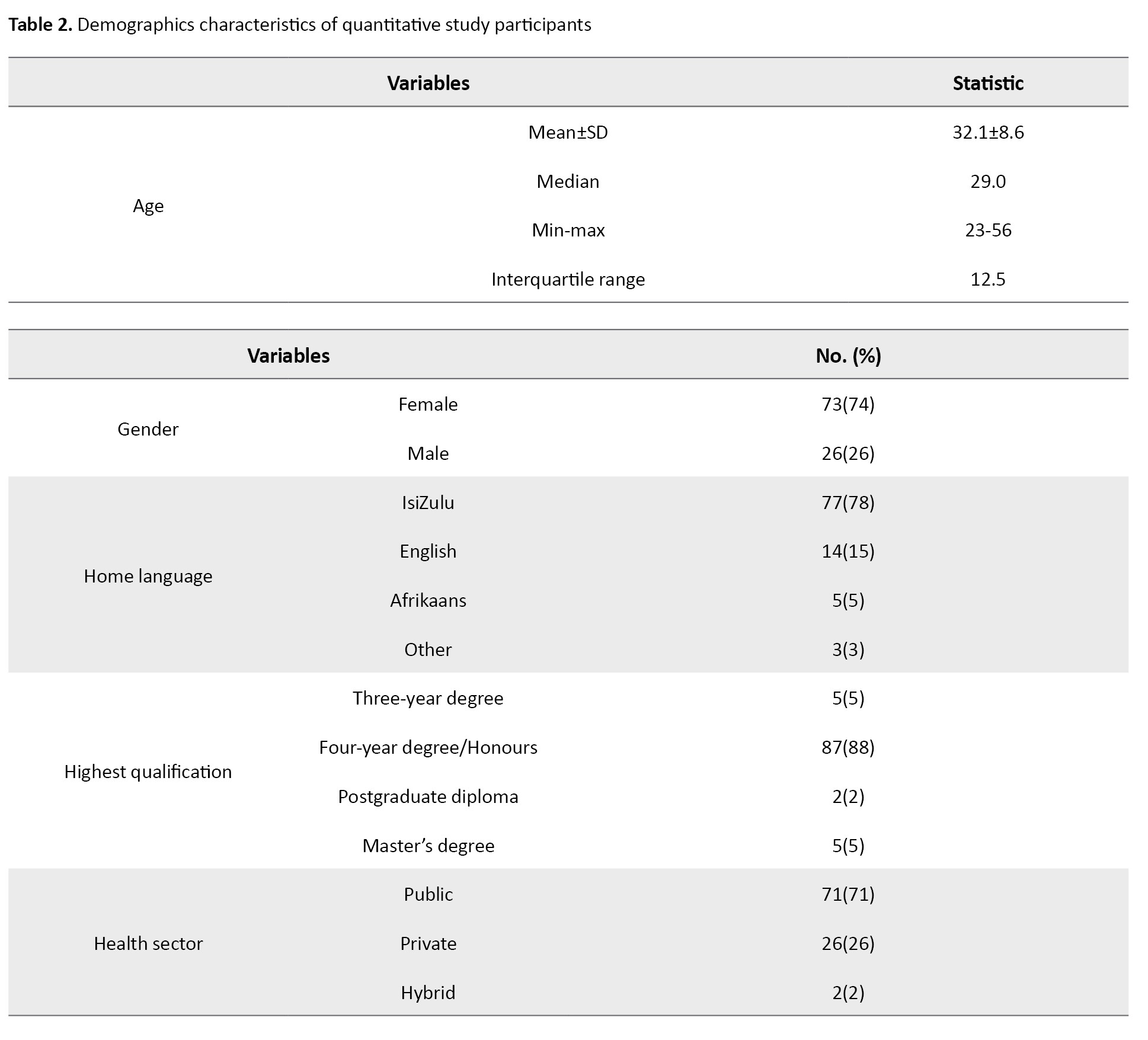

The participants included 73 women (74%) and 26 men (26%) males aged 23 to 56 years (Mean±SD, 32.1±8.6 years), as shown in Table 2.

Ninety-nine participants (78%) spoke isiZulu as their first language, with the remaining 22% spoke English, Afrikaans, or other languages. As their highest qualification, 87 participants (88%) held an Honours degree. Approximately 71% of participants (71) were from the public sector, with 2% (2) working in a hybrid situation.

Rehabilitation infrastructure

The majority (n=39, 93%) of the 42 rehabilitation services practitioners had access to assistive devices in their settings. Other rehabilitation services tools or facilities available as indicated by the 42 practitioners were plinths (n=36, 86%) and gym (n=34, 81%). Only 5/42(12%) and 4/42(10%) had access to hydrotherapy and suspension therapy respectively. Table 3 presents a joint display of quantitative and qualitative findings on rehabilitation services infrastructure.

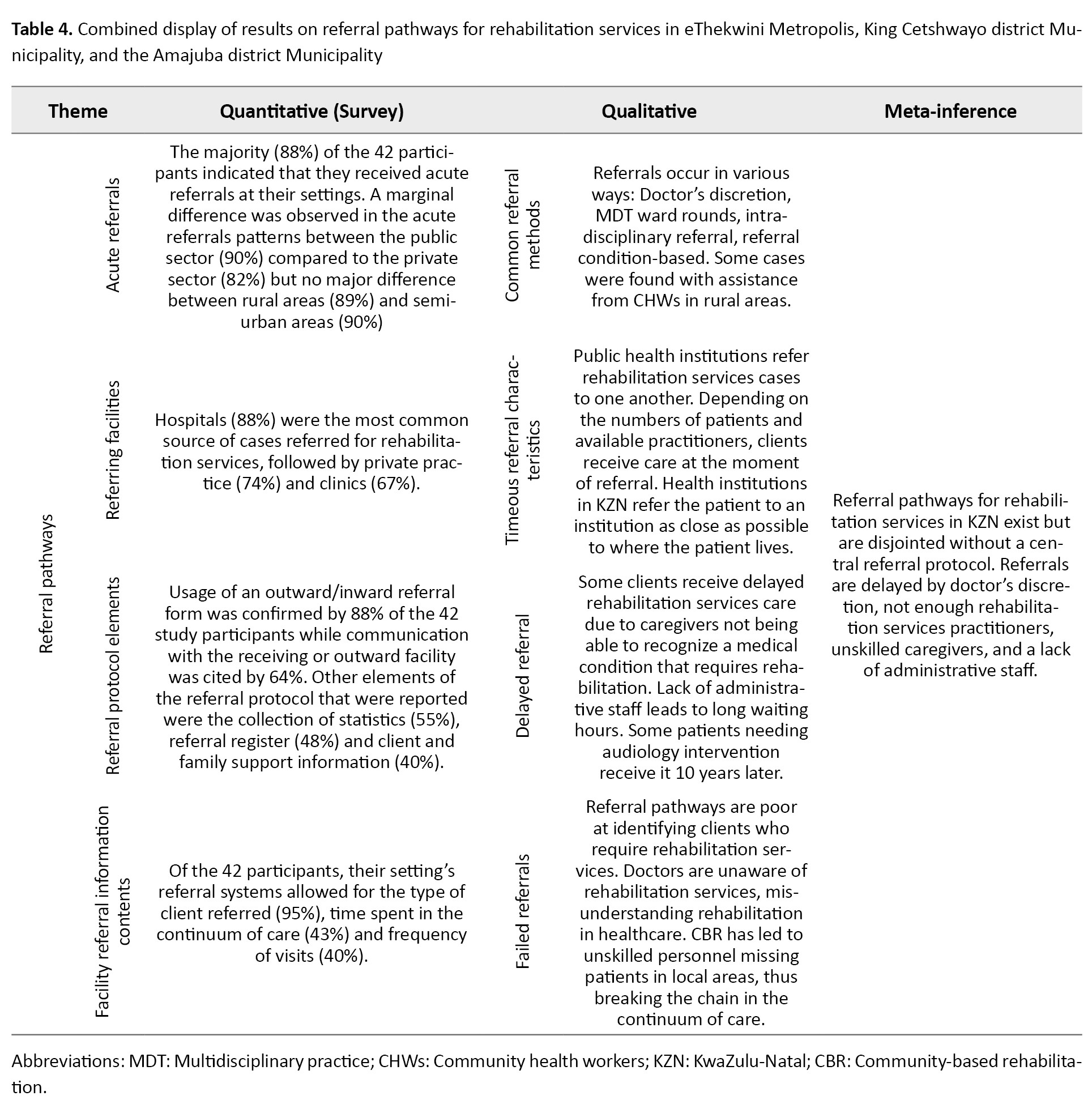

Referral pathways

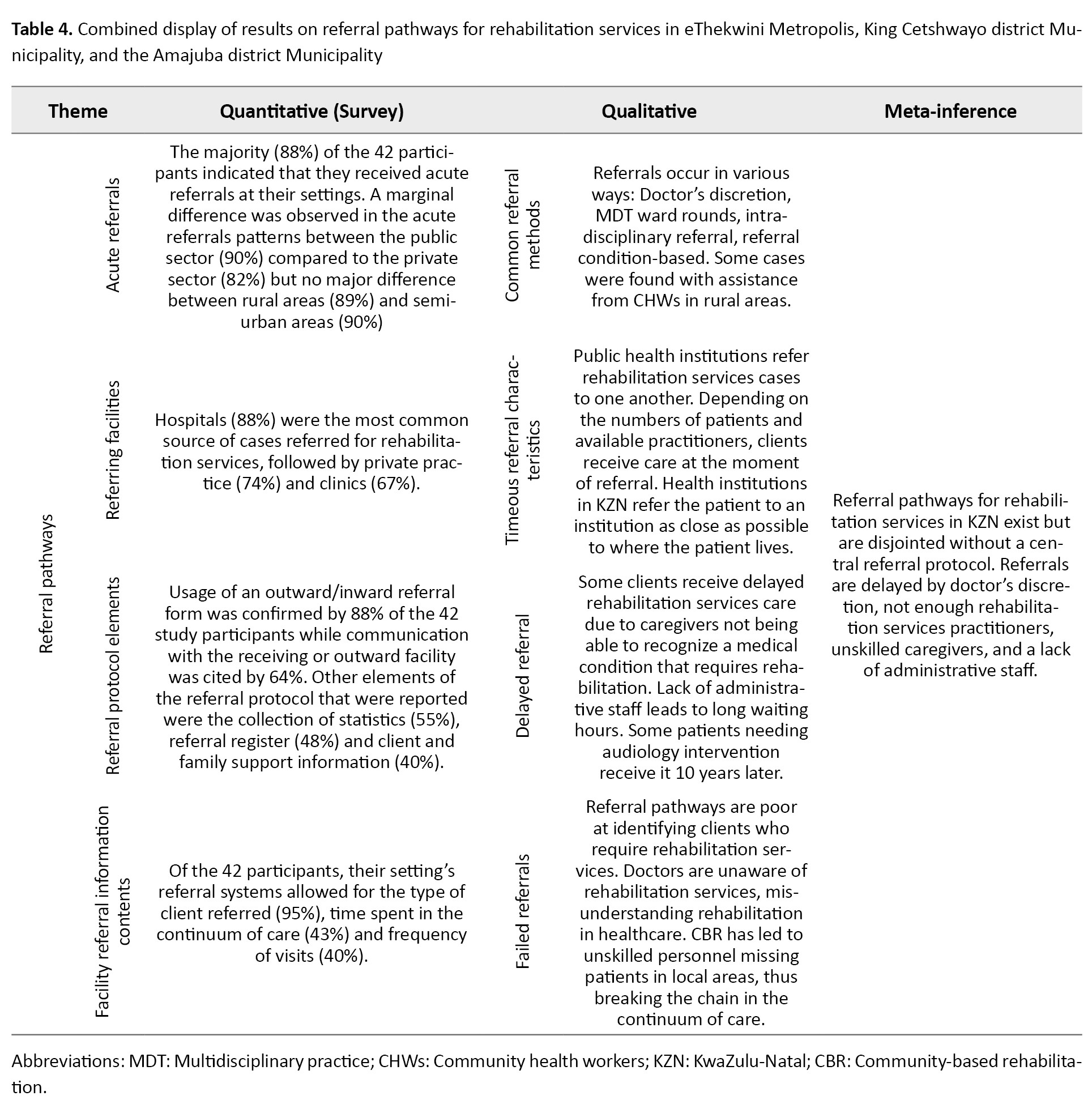

According to 41 people (98%) out of the 42 rehabilitation practitioners through which the practitioners received clients at their facilities, it was through a referral from other practitioners. Walk-in or self-referrals were confirmed by 33(79%) of the 42 participants. Table 4 presents a combined display of quantitative and qualitative findings on referral pathways in the three participating districts.

Multidisciplinary practice (MDT)

Physiotherapists were the rehabilitation services specialists with the most evidence at the facilities, with nearly 86% of the 42 study participants confirming as such. The availability of social workers was affirmed by 62% of the participants, and speech therapists by 60%. The least available were bio kineticists (24%). While the participants had a positive perception of the professional experience of rehabilitation services practitioners at their facilities (median=3.0, interquartile range [IQR]=0.5), they were significantly less satisfied with the extent to which practitioners were consulted on the recruitment of new staff (median=2.0, IQR=2.0) as well as regarding their salary packages (median=2.0, IQR=2.0). Overall satisfaction with human resources-related practices was average, with a median score of 2.8 (IQR=0.8) on the 4-point scale.

Concerning multidisciplinary practice, 42 participants (86%) indicated that they collaborated with occupational therapists the most, followed by social workers (83%). There were markedly fewer practitioners collaborating with community health workers (52%), rehabilitation assistants (45%), and community rehabilitation workers (24%). Table 5 presents a combined display of quantitative and qualitative findings on human resources for rehabilitation services in the three participating districts.

Discussion

The study was conducted to provide an in-depth analysis of the state of rehabilitation services provision in South Africa, with a particular focus on infrastructure, referral pathways, and multidisciplinary practice in selected municipal areas in the KZN Province. The results of the study reveal critical insights into the existing challenges and disparities within the rehabilitation services landscape in the province.

Quantitative evidence for rehabilitation service infrastructure indicates the presence of equipment and rehabilitation amenities, but qualitative evidence indicates almost no designated rehabilitation service units. This issue shows that rehabilitation services remain mainly within hospitals. The biomedical approach to rehabilitation services persists, as only 14% of hospitals have designated units for rehabilitation services [5]. Practitioners lamented the lack of space to provide convenient rehabilitation services.

In my opinion, rehabilitation at this institution is not good because there is no support. Thus, we are unable to provide good rehabilitation services. For one, our workplace is not convenient for patients, we work with what we have to assist the patients. As I said, there is no space, and we cannot work properly (Practitioner A1).

Most institutions visited for this study are rural-based, and floor design plans for rehabilitation service practitioners are not conducive to allied patient care. Credence is lent to this conclusion that rehabilitation services require patients to walk from one section of the hospital to the other due to the dispersed nature of the locations, for example, the physiotherapist from the occupational therapist [4, 5]. Here it should be noted that the national rehabilitation policy 2000 emphasizes the development of rehabilitation units that are accessible to communities.

The public health sector can heed lessons from the private sector which possesses such units in most districts where they service rehabilitation patients referred from acute private hospitals. These intermediate care units synchronize all rehabilitation service providers in one referral protocol by doctors [20]. The study’s results are consistent with existing literature that emphasizes the significance of a well-functioning primary healthcare system, comprehensive care, and integrated referral pathways [20]. Considering these results, the study recommends a collaborative approach to redesigning and managing a new model for rehabilitation service regarding diagnosis-related groupers, which in most cases comprise the major membership of critical rehabilitation services in KZN.

The continued institutionalization of rehabilitation services affects the referral pathways for patients. Most referral occurs between and within hospitals and local clinics. However, no standardized protocol exists; the results show disjointed and inadequate referral pathways in the three KZN districts in this study. The over-emphasis on biomedical stabilization at the hospital level causes delays for rehabilitation patients. The study highlights the discretion of doctors in controlling the accessibility of rehabilitation services for patients. The dependence on doctors’ awareness and decisions regarding rehabilitation services referrals can lead to variations in care delivery, potentially affecting the continuity of rehabilitation services [12, 28].” One practitioner for instance stated: “It means if the doctor forgets to refer to the patient and for whatever reason, or is not aware of the availability of the rehabilitation in that hospital then that patient will be missed in the system to receive rehabilitation services”.

Poor referral pathways in KZN are further compounded by unsatisfactory awareness of rehabilitation services by doctors and poor patient data record-keeping. One practitioner pointed out: “Record-keeping by the Department of Health (DoH) for rehabilitation data is nebulous and not meaningful”. Another practitioner indicated that rehabilitation service patient data collection is not much more than “head counts”. Lack of rehabilitation service awareness can lead to patients being prematurely discharged and acquiring avoidable physical complications.

Therefore, we often get patients who are close to the discharge date and you don’t have enough time to do all that you can. They say, ‘social worker, tomorrow they are leaving’ (Rehabilitation practitioner E3).

The introduction of a standardized referral protocol ought to exist across doctors, nurses and administrative staff [25]. Relevant training and workshops are required to ensure that all stakeholders know when and how to use the standard referral protocol. Monitoring and evaluation of the referral protocol needs to be followed up at the management level. Inadequate referral patterns can lead to decreased utilization of rehabilitation services, impacting patient outcomes [12, 28].

Respondents indicated the presence of most rehabilitation services practitioners, but multidisciplinary practice is minimal. The study reveals that while physiotherapists and occupational therapists are well-represented, other crucial disciplines, such as dietitians, speech therapists, audiologists, social workers, psychologists, and biokineticists are notably under-represented. The provincial representative for rehabilitation services in KZN spoke at length about how this influences patients who do not have financial resources:

“Yes, they must, we encourage them to work together you know we’re talking about patients who are struggling economically so when they come, we try to provide them with all the services, therefore they don’t have to be coming to the facility to get one service and then come back and get another service. Therefore, we encourage them to work comprehensively; but it’s (Provincial representative H2).

“- It’s ideal for me because on the ground because I work directly with disability. When you engage with the patients through the community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers you find that social workers are not part of the team (Provincial representative H1).

This skewed distribution highlights existing shortages or imbalances in the availability of different types of rehabilitation service disciplines, which impacts the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of rehabilitation service care [4-6, 13-16, 18]. The patients are sometimes referred to receive rehabilitation services, but unfortunately, few or no providers of the required rehabilitation service exist in a given hospital or setting.

As stated above, referral usually occurs within hospitals in the form of ward rounds, but such ward rounds are seldom performed with a multidisciplinary approach. A critical concern emerging from the study is the high therapist-to-patient ratio reported in both public and private care settings [4-6, 13-16, 18]. This disparity can strain rehabilitation service professionals, negatively affecting the quality and timeliness of rehabilitation service care provided to patients in KZN. High rehabilitation patient numbers hamper adequate multidisciplinary practice because too few practitioners exist to provide time to service all patients within a multidisciplinary approach. One practitioner stated: “I think what counts against us is time because we’re short-staffed, we don’t have the time to sit together and do that planning (Practitioner P2).

Patients without receiving multidisciplinary rehabilitation services face premature discharge due to bed demand. This issue leads to avoidable complications, such as contractures. If these patients are fortunate, they are later identified by community rehabilitation workers. However, limited knowledge in providing rehabilitation services by community rehabilitation workers leads to unsatisfactory results. Administrative staff shortages complicate the situation further as they coordinate referrals between disciples. Low administrative staff numbers lead to an inefficient referral process, resulting in rehabilitation services patients being lost in the system.

Furthermore, the study underscores the fragmented nature of rehabilitation service disciplines, particularly in rural areas. This fragmentation poses challenges in delivering holistic and comprehensive rehabilitation service care, which is essential to address the diverse needs of patients. One practitioner stated: “Public rehabilitation overwhelmed, almost no time for MDT.” The shortage of rehabilitation service providers, coupled with the fragmented nature of services, can contribute to inequities in rehabilitation service delivery, particularly between urban and rural populations in the province.

The study underscores the need for policy development, rehabilitation service skill enhancement, and quality assurance mechanisms to support the proposed intermediate care units. By leveraging the strengths of both the public and private sectors, this model has the potential to address the challenges identified in the study and improve the accessibility and quality of rehabilitation healthcare services in KZN.

Conclusion

This study’s analysis sheds light on the intricacies of rehabilitation healthcare service provision in KZN, South Africa. The challenges identified regarding referral pathways, discipline distribution, high therapist-to-patient ratios, lack of designated rehabilitation service units, and rural disparities in rehabilitation services access underscore the urgency for a collaborative effort for innovative solutions. By addressing these challenges and implementing the proposed model of district-based intermediate care units, policymakers, healthcare institutions and stakeholders can work together to enhance rehabilitation service delivery and ensure equitable access to quality services within the province. It is hoped that this study will serve as a foundation for future initiatives aimed at transforming and improving rehabilitation services in the region.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal's Biomedical Research (Code: BREC/00001338/2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the purpose of the study was explained. Additionally, the participants’ permission to audio-visually-record interviews was obtained. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertartion of Senzelwe M. Mazibuko, approved by Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal and the author received tuition remission for PhD studies University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

Authors' contributions

Data collection, data analysis and writing the original draft: Senzelwe M. Mazibuko; Review and editing: Thayananthee Nadasan and Pragashnie Govender; Conceptualization and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Despite South Africa being a signatory to the national rehabilitation policy [1] and the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities [2], access to rehabilitation services remains a challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings [3-8]. Specifically, in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Province, South Africa, patients face difficulties in accessing rehabilitation services due to limited infrastructure, disjointed referral pathways, lack of patient involvement, transport costs, shortage of rehabilitation service disciplines, and geographically inaccessible institutions [5, 8]. The public health system’s capacity to provide rehabilitation services in KZN is limited and does not adequately address the population’s needs [5, 8, 9].

As healthcare services improve and the population lives longer, non-communicable diseases, such as stroke, diabetes, and cerebrospinal conditions are increasing [8, 10, 11]. However, these conditions are not being diagnosed at admission, and there is a lack of standardized rehabilitation service treatment plans [8, 12]. Providing appropriate rehabilitation services requires a multidisciplinary approach involving various healthcare professionals, namely physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, speech therapists, audiologists and nutritionists [4, 6, 13-19]. However, rehabilitation service teams in South Africa are imbalanced and incomplete due to a lack of funding for personnel [5, 13, 15-18].

Moreover, rehabilitation services infrastructure in the form of designated rehabilitation service units at district hospitals is almost non-existent [3-6, 9]. Such designated rehabilitation service units can be described as intermediate care facilities that restore the functional status of rehabilitation service patients through a multidisciplinary practice at lower-intensity care than an acute institution [20].

There is also a lack of informative research on indicators for appropriate rehabilitation services development, and no standard operating procedure guides the provision of rehabilitation services in KZN [9]. Referral pathways are irregular, leading to inadequate follow-up and avoidable complications for clients [3-6, 9]. Additionally, the field of rehabilitation services lacks innovation, with human resources being paper-driven and lacking preparedness for the fourth industrial revolution [21]. The South African government faces resource challenges in improving the healthcare system, including fiscal shortages, constrained innovation, stagnant technological advancement, and poor human resources for healthcare [20, 22, 23]. As a result, the increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases in rural areas puts pressure on the rehabilitation services system [3-6].

Biomedical practitioners at the clinical level focus on patient stabilization and are inappropriately aware of rehabilitation services [3-6]. As such, rehabilitation services data-capturing is nebulous and not meaningful. Rehabilitation service patients rely on traditional clinical practice that considers rehabilitation services as being separate from clinical care [3-6, 9]. Rehabilitation services patients are referred later than advisable for recovery. Due to chronic shortages of rehabilitation staff, services are usually in urban areas, far from the patient’s admission hospital. Rehabilitation service referral pathways lack a case-based system to categorize patients with similar clinical diagnoses to control costs (diagnosis-related groupers). This issue results in high costs for transport and long waiting times for sessions, resulting in fatigue and patients being lost in the system of the continuum of care [24].

In the South African government’s quest to re-engineer primary healthcare [25, 26], rehabilitation services have been identified as an integral feature of a transformed public health system [9]. As a result, scientific evidence is essential to inform South Africa’s Department of Health (DoH) in its quest. Therefore, this study was conducted to profile the status of rehabilitation service provision in South Africa regarding infrastructure, referral pathways, human resource practices, and multidisciplinary practices in KZN Province.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study utilized the viable system model (VSM) as its theoretical framework to analyze rehabilitation infrastructure, referrals, and multidisciplinary practices in KZN. VSM, a systems theory, emphasizes the importance of external regulation for organizational success. The study employed a concurrent mixed-methods design, combining qualitative (focus group discussions) and quantitative (cross-sectional survey) approaches. This design aimed to comprehensively describe current rehabilitation practices in KZN, focusing on infrastructure, referral pathways, human resources, and multidisciplinary practices.

Study population and sample description

The population included rehabilitation practitioners, district rehabilitation services managers, and policymakers from Amajuba District Municipality, King Cetshwayo District Municipality and the eThekwini Metropolis in KZN. Non-probability stratified and maximum variation purposive sampling were employed to recruit 99 participants. The qualitative component involved 57 participants, including practitioners, managers, and representatives from relevant departments. The quantitative component sampled 42 practitioners using the snowball method, representing different districts (Table 1).

Data collection

Data collection commenced after the COVID-19 period, with quantitative surveys distributed before qualitative focus groups. Separate interviews were conducted for managers and practitioners. Interview schedules were designed collaboratively and piloted for refinement. Data collection involved one-to-one interviews, focus groups, and surveys conducted over two months. For the qualitative data collection, interview schedules were designed to profile data specific to different districts and focused on the current status and practices of rehabilitation services. Trustworthiness was ensured through the researcher’s extensive experience and the use of actual quotes from participants. Interviews were between 30 and 60 minutes. Two one-to-one interviews were conducted with social development representatives from the King Cetshwayo District. Two focus groups were conducted by the researcher with rehabilitation service practitioners from the Amajuba District Municipality and the King Cetshwayo District Municipality. Three focus groups were conducted by the researcher with rehabilitation services practitioners in the eThekwini Metro and the King Cetshwayo District Municipality. One focus group was held with 2 provincial health representatives. The duration of the focus groups was between 30 to 40 minutes. Regarding quantitative data collection, a survey tool designed by the researcher and supervisors, aimed to enhance qualitative data. It consisted of six sections covering demographic profiles, rehabilitation practice, referral pathways, facility information, quality control processes, and service delivery. Likert scales and closed-ended multiple-choice items were utilized (Appendix A).

Appendix A: Data collection tool

Introduction

Dear participant. You have been invited to be a part of this Doctoral research study because you are a medical rehabilitation practitioner in the King Cetshwayo District, Amajuba District, or the eThekwini Municipality District. This survey is a part of the study’s data collection. The study aims to create a model for the provision of medical rehabilitation services that are timeous, equitable, multidisciplinary and accessible to as many clients at the district and local level of care.

Your participation in this field research will provide quantitative expert opinion on medical rehabilitation from those who provide it on a daily basis. This survey will be used for data on the status of rehabilitation, equitable access to medical rehabilitation, multidisciplinary practice and the national health insurance’s consideration of medical rehabilitation. This survey will gather information on socio-demographics, human resources for medical rehabilitation, referral pathways, rehabilitation facility information, quality control processes and service delivery. The subjective, personal and qualitative experiences gained from this interview will inform the researcher construct a model for District-based medical rehabilitation care.

Objectives

To conduct a scoping review of PPP usage for rehabilitation service delivery in KZN.

Establish referral pathway practices for rehabilitation service, to establish current human resource practices for rehabilitation, and to establish current access to rehabilitation services in KZN.

Improve human resources for rehabilitation by re-engineering multidisciplinary practice in KZN. Improve access to rehabilitation infrastructure through the intermediate care approach at the district health system.

Ascertain and forecast cost risks to rehabilitation services from RAF and COIDA case managers and compensation office representative respectively.

Review level to which rehabilitation is considered by NHI Bill with participants. Assess participants’ views on operational mechanisms of universally covered rehabilitation services.

Solicit expertise and the experiences of rehabilitation practitioners, managers, NGOs and patients respectively to develop model of rehabilitation service provision in KZN.

To identify strategies for stakeholder uptake and potential threats to the implementation of the model.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes [27]. Quantitative data were captured using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using IBM SPSS software, version 24. The study ensured confirmability and dependability through an audit trail and the reflexivity of the researcher. Credibility was enhanced through data triangulation and thick description, ensuring the transferability of findings through consideration of context and participant experiences.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

The participants included 73 women (74%) and 26 men (26%) males aged 23 to 56 years (Mean±SD, 32.1±8.6 years), as shown in Table 2.

Ninety-nine participants (78%) spoke isiZulu as their first language, with the remaining 22% spoke English, Afrikaans, or other languages. As their highest qualification, 87 participants (88%) held an Honours degree. Approximately 71% of participants (71) were from the public sector, with 2% (2) working in a hybrid situation.

Rehabilitation infrastructure

The majority (n=39, 93%) of the 42 rehabilitation services practitioners had access to assistive devices in their settings. Other rehabilitation services tools or facilities available as indicated by the 42 practitioners were plinths (n=36, 86%) and gym (n=34, 81%). Only 5/42(12%) and 4/42(10%) had access to hydrotherapy and suspension therapy respectively. Table 3 presents a joint display of quantitative and qualitative findings on rehabilitation services infrastructure.

Referral pathways

According to 41 people (98%) out of the 42 rehabilitation practitioners through which the practitioners received clients at their facilities, it was through a referral from other practitioners. Walk-in or self-referrals were confirmed by 33(79%) of the 42 participants. Table 4 presents a combined display of quantitative and qualitative findings on referral pathways in the three participating districts.

Multidisciplinary practice (MDT)

Physiotherapists were the rehabilitation services specialists with the most evidence at the facilities, with nearly 86% of the 42 study participants confirming as such. The availability of social workers was affirmed by 62% of the participants, and speech therapists by 60%. The least available were bio kineticists (24%). While the participants had a positive perception of the professional experience of rehabilitation services practitioners at their facilities (median=3.0, interquartile range [IQR]=0.5), they were significantly less satisfied with the extent to which practitioners were consulted on the recruitment of new staff (median=2.0, IQR=2.0) as well as regarding their salary packages (median=2.0, IQR=2.0). Overall satisfaction with human resources-related practices was average, with a median score of 2.8 (IQR=0.8) on the 4-point scale.

Concerning multidisciplinary practice, 42 participants (86%) indicated that they collaborated with occupational therapists the most, followed by social workers (83%). There were markedly fewer practitioners collaborating with community health workers (52%), rehabilitation assistants (45%), and community rehabilitation workers (24%). Table 5 presents a combined display of quantitative and qualitative findings on human resources for rehabilitation services in the three participating districts.

Discussion

The study was conducted to provide an in-depth analysis of the state of rehabilitation services provision in South Africa, with a particular focus on infrastructure, referral pathways, and multidisciplinary practice in selected municipal areas in the KZN Province. The results of the study reveal critical insights into the existing challenges and disparities within the rehabilitation services landscape in the province.

Quantitative evidence for rehabilitation service infrastructure indicates the presence of equipment and rehabilitation amenities, but qualitative evidence indicates almost no designated rehabilitation service units. This issue shows that rehabilitation services remain mainly within hospitals. The biomedical approach to rehabilitation services persists, as only 14% of hospitals have designated units for rehabilitation services [5]. Practitioners lamented the lack of space to provide convenient rehabilitation services.

In my opinion, rehabilitation at this institution is not good because there is no support. Thus, we are unable to provide good rehabilitation services. For one, our workplace is not convenient for patients, we work with what we have to assist the patients. As I said, there is no space, and we cannot work properly (Practitioner A1).

Most institutions visited for this study are rural-based, and floor design plans for rehabilitation service practitioners are not conducive to allied patient care. Credence is lent to this conclusion that rehabilitation services require patients to walk from one section of the hospital to the other due to the dispersed nature of the locations, for example, the physiotherapist from the occupational therapist [4, 5]. Here it should be noted that the national rehabilitation policy 2000 emphasizes the development of rehabilitation units that are accessible to communities.

The public health sector can heed lessons from the private sector which possesses such units in most districts where they service rehabilitation patients referred from acute private hospitals. These intermediate care units synchronize all rehabilitation service providers in one referral protocol by doctors [20]. The study’s results are consistent with existing literature that emphasizes the significance of a well-functioning primary healthcare system, comprehensive care, and integrated referral pathways [20]. Considering these results, the study recommends a collaborative approach to redesigning and managing a new model for rehabilitation service regarding diagnosis-related groupers, which in most cases comprise the major membership of critical rehabilitation services in KZN.

The continued institutionalization of rehabilitation services affects the referral pathways for patients. Most referral occurs between and within hospitals and local clinics. However, no standardized protocol exists; the results show disjointed and inadequate referral pathways in the three KZN districts in this study. The over-emphasis on biomedical stabilization at the hospital level causes delays for rehabilitation patients. The study highlights the discretion of doctors in controlling the accessibility of rehabilitation services for patients. The dependence on doctors’ awareness and decisions regarding rehabilitation services referrals can lead to variations in care delivery, potentially affecting the continuity of rehabilitation services [12, 28].” One practitioner for instance stated: “It means if the doctor forgets to refer to the patient and for whatever reason, or is not aware of the availability of the rehabilitation in that hospital then that patient will be missed in the system to receive rehabilitation services”.

Poor referral pathways in KZN are further compounded by unsatisfactory awareness of rehabilitation services by doctors and poor patient data record-keeping. One practitioner pointed out: “Record-keeping by the Department of Health (DoH) for rehabilitation data is nebulous and not meaningful”. Another practitioner indicated that rehabilitation service patient data collection is not much more than “head counts”. Lack of rehabilitation service awareness can lead to patients being prematurely discharged and acquiring avoidable physical complications.

Therefore, we often get patients who are close to the discharge date and you don’t have enough time to do all that you can. They say, ‘social worker, tomorrow they are leaving’ (Rehabilitation practitioner E3).

The introduction of a standardized referral protocol ought to exist across doctors, nurses and administrative staff [25]. Relevant training and workshops are required to ensure that all stakeholders know when and how to use the standard referral protocol. Monitoring and evaluation of the referral protocol needs to be followed up at the management level. Inadequate referral patterns can lead to decreased utilization of rehabilitation services, impacting patient outcomes [12, 28].

Respondents indicated the presence of most rehabilitation services practitioners, but multidisciplinary practice is minimal. The study reveals that while physiotherapists and occupational therapists are well-represented, other crucial disciplines, such as dietitians, speech therapists, audiologists, social workers, psychologists, and biokineticists are notably under-represented. The provincial representative for rehabilitation services in KZN spoke at length about how this influences patients who do not have financial resources:

“Yes, they must, we encourage them to work together you know we’re talking about patients who are struggling economically so when they come, we try to provide them with all the services, therefore they don’t have to be coming to the facility to get one service and then come back and get another service. Therefore, we encourage them to work comprehensively; but it’s (Provincial representative H2).

“- It’s ideal for me because on the ground because I work directly with disability. When you engage with the patients through the community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers you find that social workers are not part of the team (Provincial representative H1).

This skewed distribution highlights existing shortages or imbalances in the availability of different types of rehabilitation service disciplines, which impacts the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of rehabilitation service care [4-6, 13-16, 18]. The patients are sometimes referred to receive rehabilitation services, but unfortunately, few or no providers of the required rehabilitation service exist in a given hospital or setting.

As stated above, referral usually occurs within hospitals in the form of ward rounds, but such ward rounds are seldom performed with a multidisciplinary approach. A critical concern emerging from the study is the high therapist-to-patient ratio reported in both public and private care settings [4-6, 13-16, 18]. This disparity can strain rehabilitation service professionals, negatively affecting the quality and timeliness of rehabilitation service care provided to patients in KZN. High rehabilitation patient numbers hamper adequate multidisciplinary practice because too few practitioners exist to provide time to service all patients within a multidisciplinary approach. One practitioner stated: “I think what counts against us is time because we’re short-staffed, we don’t have the time to sit together and do that planning (Practitioner P2).

Patients without receiving multidisciplinary rehabilitation services face premature discharge due to bed demand. This issue leads to avoidable complications, such as contractures. If these patients are fortunate, they are later identified by community rehabilitation workers. However, limited knowledge in providing rehabilitation services by community rehabilitation workers leads to unsatisfactory results. Administrative staff shortages complicate the situation further as they coordinate referrals between disciples. Low administrative staff numbers lead to an inefficient referral process, resulting in rehabilitation services patients being lost in the system.

Furthermore, the study underscores the fragmented nature of rehabilitation service disciplines, particularly in rural areas. This fragmentation poses challenges in delivering holistic and comprehensive rehabilitation service care, which is essential to address the diverse needs of patients. One practitioner stated: “Public rehabilitation overwhelmed, almost no time for MDT.” The shortage of rehabilitation service providers, coupled with the fragmented nature of services, can contribute to inequities in rehabilitation service delivery, particularly between urban and rural populations in the province.

The study underscores the need for policy development, rehabilitation service skill enhancement, and quality assurance mechanisms to support the proposed intermediate care units. By leveraging the strengths of both the public and private sectors, this model has the potential to address the challenges identified in the study and improve the accessibility and quality of rehabilitation healthcare services in KZN.

Conclusion

This study’s analysis sheds light on the intricacies of rehabilitation healthcare service provision in KZN, South Africa. The challenges identified regarding referral pathways, discipline distribution, high therapist-to-patient ratios, lack of designated rehabilitation service units, and rural disparities in rehabilitation services access underscore the urgency for a collaborative effort for innovative solutions. By addressing these challenges and implementing the proposed model of district-based intermediate care units, policymakers, healthcare institutions and stakeholders can work together to enhance rehabilitation service delivery and ensure equitable access to quality services within the province. It is hoped that this study will serve as a foundation for future initiatives aimed at transforming and improving rehabilitation services in the region.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal's Biomedical Research (Code: BREC/00001338/2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the purpose of the study was explained. Additionally, the participants’ permission to audio-visually-record interviews was obtained. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertartion of Senzelwe M. Mazibuko, approved by Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal and the author received tuition remission for PhD studies University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

Authors' contributions

Data collection, data analysis and writing the original draft: Senzelwe M. Mazibuko; Review and editing: Thayananthee Nadasan and Pragashnie Govender; Conceptualization and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Republic of South Africa, Department of Health. Rehabilitation for all: National Rehabilitation Policy. Pretoria: Government Printers; 2000. [Link]

- United Nations. United nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities [Internet]. 2006 [Updated 2024 June 23]. Available from: [Link]

- Visagie S, Scheffler E, Schneider M. Policy implementation in wheelchair service delivery in a rural South African setting. Afr J Disabil. 2013; 2(1):63. [DOI:10.4102/ajod.v2i1.63] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Visagie S, Swartz L. Rural South Africans' rehabilitation experiences: Case studies from the Northern Cape Province. S Afr J Physiother. 2016; 72(1):298. [DOI:10.4102/sajp.v72i1.298] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Naidoo U, Ennion L. Barriers and facilitators to utilisation of rehabilitation services amongst persons with lower-limb amputations in a rural community in South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019; 43(1):95-103. [DOI:10.1177/0309364618789457] [PMID]

- Sherry K. Disability and rehabilitation: Essential considerations for equitable, accessible and poverty-reducing health care in South Africa. South Afr Health Rev. 2014; 2014(1):89-99. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Rehabilitation in health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Link]

- Louw QA, Conradie T, Xuma-Soyizwapi N, Davis-Ferguson M, White J, Stols M, et al. Rehabilitation capacity in South Africa-A situational analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3579. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20043579] [PMID] [PMCID]

- National Department of Health. Framework and strategy for disability and rehabilitation services in South Africa 2015-2020. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015. [Link]

- Louw Q, Grimmer K, Berner K, Conradie T, Bedada DT, Jesus TS. Towards a needs-based design of the physical rehabilitation workforce in South Africa: trend analysis [1990-2017] and a 5-year forecasting for the most impactful health conditions based on global burden of disease estimates. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):913. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10962-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ntsiea V, Mudzi W, Maleka D, Comley-White N, Pilusa S. Barriers and facilitators of using outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation in South Africa. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2022; 29(2):1-15. [DOI:10.12968/ijtr.2020.0126]

- Conradie T, Charumbira M, Bezuidenhout M, Leong T, Louw Q. Rehabilitation and primary care treatment guidelines, South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2022; 100(11):689-98. [DOI:10.2471/BLT.22.288337] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dayal H. Provision of rehabilitation services within the District Health System-the experience of rehabilitation managers in facilitating this right for people with disabilities. South Afr J Occup Ther. 2010; 40(1):22-6. [Link]

- Kahonde C, Mlenzana N, Rhoda A. Persons with physical disabilities’ experiences of rehabilitation services at community health centres in Cape Town. South Afr J Physiother. 2010; 66(3):2-7. [DOI:10.4102/sajp.v66i3.67]

- Mji G, Chappell P, Statham S, Mlenzana N, Goliath C, De Wet C, et al. Understanding the current discourse of rehabilitation: With reference to disability models and rehabilitation policies for evaluation research in the South African Setting. South Afr J Physiother. 2013; 69(2):a22. [DOI:10.4102/sajp.v69i2.22]

- Suchman L, Hart E, Montagu D. Public-private partnerships in practice: collaborating to improve health finance policy in Ghana and Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2018; 33(7):777-85. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czy064] [PMID] [PMCID]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World report on disability Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2011. [Link]

- Mauk KL. Rehabilitation nursing: A contemporary approach to practice. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012. [Link]

- A Mabunda S, London L, Pienaar D. An evaluation of the role of an intermediate care facility in the continuum of care in Western Cape, South Africa. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018; 7(2):167-79. [DOI:10.15171/ijhpm.2017.52] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Magaqa Q, Ariana P, Polack S. Examining the availability and accessibility of rehabilitation services in a rural district of South Africa: A mixed-methods study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4692. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18094692] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kula N, Fryatt RJ. Public-private interactions on health in South Africa: Opportunities for scaling up. Health Policy Plan. 2014; 29(5):560-9. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czt042] [PMID]

- Walwyn DR, Nkolele AT. An evaluation of South Africa's public-private partnership for the localisation of vaccine research, manufacture and distribution. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018; 16(1):30. [DOI:10.1186/s12961-018-0303-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hanass-Hancock J, Nene S, Deghaye N, Pillay S. 'These are not luxuries, it is essential for access to life': Disability related out-of-pocket costs as a driver of economic vulnerability in South Africa. Afr J Disabil. 2017; 6:280. [DOI:10.4102/ajod.v6i0.280] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Myezwa H, Van Niekerk M. National health insurance implications for rehabilitation professionals and service delivery. South Afr J Physiother. 2013; 69(4):3-9. [DOI:10.4102/sajp.v69i4.372]

- Government Gazette. White paper on the rights of persons with disabilities. Pretoria: Goverment Gazette; 2016. [Link]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3(2):77-101. [DOI:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa]

- van Biljon H, van Niekerk L, Margot-Cattin I, Adams F, Plastow N, Bellagamba D, et al. The health equity characteristics of research exploring the unmet community mobility needs of older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022; 22(1):808. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03492-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Physiotherapy

Received: 2024/03/12 | Accepted: 2024/04/13 | Published: 2024/07/21

Received: 2024/03/12 | Accepted: 2024/04/13 | Published: 2024/07/21