Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Oyewole O O, Thanni L O, Ogunlana M O, Adebanjo A A, Fafolahan A O, Odole A C et al . A Qualitative Inquiry Exploring Recovery From Lower Extremity Fractures. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-334-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-334-en.html

Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole *1

, Lateef Olatunji Thanni2

, Lateef Olatunji Thanni2

, Michael Opeoluwa Ogunlana3

, Michael Opeoluwa Ogunlana3

, Adekunle Abayomi Adebanjo2

, Adekunle Abayomi Adebanjo2

, Abiola Olayinka Fafolahan4

, Abiola Olayinka Fafolahan4

, Adesola Christianah Odole5

, Adesola Christianah Odole5

, Pragashnie Govender6

, Pragashnie Govender6

, Lateef Olatunji Thanni2

, Lateef Olatunji Thanni2

, Michael Opeoluwa Ogunlana3

, Michael Opeoluwa Ogunlana3

, Adekunle Abayomi Adebanjo2

, Adekunle Abayomi Adebanjo2

, Abiola Olayinka Fafolahan4

, Abiola Olayinka Fafolahan4

, Adesola Christianah Odole5

, Adesola Christianah Odole5

, Pragashnie Govender6

, Pragashnie Govender6

1- Department of Physiotherapy, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria. & Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. , OyewoleO1@ukzn.ac.za

2- Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

3- Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. & Department of Physiotherapy, Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, P.M.B. 3031, Abeokuta, Nigeria

4- Department of Physiotherapy, Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, P.M.B. 3031, Abeokuta, Nigeria & Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

5- Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

6- Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

2- Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

3- Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. & Department of Physiotherapy, Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, P.M.B. 3031, Abeokuta, Nigeria

4- Department of Physiotherapy, Federal Medical Centre, Abeokuta, P.M.B. 3031, Abeokuta, Nigeria & Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

5- Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

6- Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa.

Keywords: Lower extremity fracture, Patient experience, Patient values, Recovery experiences, lived experiences, Nigeria, Rehabilitation

Full-Text [PDF 660 kb]

(89 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (286 Views)

Full-Text: (29 Views)

Introduction

In Nigeria and many other developing countries, road users face increased risk of traumatic injuries due to inadequate road infrastructure, high traffic volumes, insufficient driver training, poor law enforcement, and lack of physical separation between vehicles and vulnerable road users [1]. Lower extremity bones have been consistently reported as primarily affected in road traffic injuries (RTIs), [2] with tibia/fibula fractures ranking highest, followed by femur fractures in Nigeria [3-5]. The shift toward motorcycle transportation in many rural communities has substantially contributed to these RTIs [2]. The consequences of lower extremity trauma among RTI victims include profound physical suffering and ongoing social and economic costs [6, 7].

The impact of sustaining a lower extremity fracture (LEF) can be life-altering, with prolonged recovery periods that fundamentally affect patients’ quality of life [8]. These impacts encompass delayed return to work, [9] job loss and economic burden [7, 9, 10], disruption of everyday social life and social isolation, [11] family life disruption, [12] sleep deprivation, compromised sense of independence, and diminished psychological well-being [13]. Furthermore, injuries affecting mobility have broad quality of life and economic consequences for both patients and their family members [6, 14-16].

Bone fractures constitute a major global public health concern, accounting for 178 million new cases (78 million involving LEF) in 2019, representing a 33.4% increase since 1990 [17]. The age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates of bone fractures in Nigeria are particularly concerning, with 1100.5 per 100000 and 3190.0 per 100000 population in 2019, demonstrating increases of 5.6% and 4.1% respectively from 1990 [17]. This translates to approximately 193 years lived with disabilities per 100,000 Nigerians in 2019, potentially attributed to increased disability-adjusted life years due to rising RTIs forecasted to double by 2030 in sub-Saharan Africa [1].

Evidence from medical literature suggests that LEF healing typically occurs 3 months post-injury, with patients expected to recover to pre-injury health status within 6 months [14, 18]. However, clinical recovery often does not translate to meaningful functional recovery based on patients’ perceptions and lived experiences. Recent data indicate that Nigerians with LEFs do not return to their pre-injury health status 6 months after LEF [19].

Patient-centered rehabilitation, which prioritizes patients’ perspectives and values, represents one approach to mitigate the burden of LEF. Previous studies exploring the lived experiences of patients with LEF have revealed critical recovery priorities [6, 8, 13, 20-22]. Key areas identified as important include walking, gait and mobility, being able to return to life roles, pain or discomfort, and quality of life [23].

However, extrapolating patients’ lived experiences during recovery may be limited by variations in healthcare systems across countries, particularly when comparing developed nations with lower-middle-income countries like Nigeria. The absence of structured care transitions for Nigerians with LEFs often limits care pathways. In contrast to healthcare systems in developed countries, where patients transition from surgical hospitals to specialized post-acute care facilities [24], Nigerian secondary and tertiary health facilities provide both postoperative care and rehabilitation during prolonged hospital stays. Healthcare financing remains approximately 70% out-of-pocket for most Nigerian patients, with less than 5% of the population having enrolled in health insurance [25].

There is limited information on how Nigerians with LEFs experience the transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home, their recovery experiences, and what matters most to them during their community-based recovery journey. Including the perspectives of Nigerian patients with LEF may improve the quality of care and recovery outcomes [26] while helping to formulate culturally appropriate patient-centered rehabilitation approaches [13]. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of Nigerian patients with LEF, identify what patients consider essential during recovery, and examine how these priorities can inform the evaluation of LEF service quality and patient-centered care approaches.

Patients and Methods

This qualitative study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative (COREQ) research guidelines [27].

Study Design

Theoretical framework

A qualitative, exploratory study was adopted to capture and comprehensively describe the lived experiences of Nigerian patients with LEF during their recovery. The focus was on understanding and describing experiences as they are authentically lived and felt by individuals [28].

Participant Selection

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants representing various types of LEFs, ages, and genders. Ten participants were recruited until data redundancy was achieved, ensuring comprehensive capture of diverse experiences. The inclusion criteria comprised participants who had been discharged from inpatient care, achieved clinical :union: of their LEF, were ≥12 weeks post-injury, and were able to provide informed consent for interviews. Exclusion criteria included patients with non-clinical :union:, <12 weeks post-injury, and those unable to consent to the interview. The sampling process spanned 11 months.

Study setting

In-depth interviews were conducted by the principal investigator in a noise-free, private cubicle (face-to-face) or via telephone to ensure participant comfort and confidentiality. All participants were outpatients at the Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

Data collection

Before interviews, a structured pro forma was used to collect comprehensive sociodemographic and clinical information. Clinical details, including the date of fracture onset, fracture type, length of hospitalization, and treatment modality, were extracted from patients’ hospital records. Sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, education level, and occupation, were systematically documented.

A semi-structured interview guide facilitated consistent yet flexible exploration of experiences across all interviews. Strategic probes were employed to capture detailed information during interviews as appropriate. The interview guide contained carefully constructed questions that elicited participants’ lived experiences during recovery and the factors they considered most important. Participants were asked to describe their typical day and explain how LEF affected their daily lives, including impacts on their mood, walking ability, work capacity, leisure activities, and family relationships. To better understand recovery priorities, participants were asked to identify the most significant factors in their recovery and to compare their daily lives before and after LEF. When necessary, targeted probes were utilized to elicit temporal, procedural, or detailed information.

Interviews were audio-recorded, with reflective annotations to support accurate interpretation of the interview data. Interviews were conducted in either English or Yoruba, depending on participants’ language preferences, and lasted 30 to 45 minutes. The interview guide was professionally translated into Yoruba and back-translated by language experts to ensure data credibility and cultural appropriateness. Trustworthiness in the study was maintained through strategies that included member checking, triangulation during data analysis, an audit trail maintained from conception through to analysis, the research team’s reflexivity, and attempts at thick description in the reporting of the data.

Data analysis

Interviews were recorded using encrypted digital audio recorders and securely downloaded to password-protected laptops accessible only to the lead researcher. All interviews were transcribed verbatim with identifiable information removed to ensure participant confidentiality. Interview transcripts were stored on secure, password-protected devices and pseudonymized using unique study identification numbers. The lead author thoroughly reviewed all transcripts to achieve deep familiarity with the data. Data organization and analysis were completed using ATLAS.ti software, version 24 package. Transcripts were independently coded by two authors, with regular discussion sessions among researchers to ensure agreement, dependability, and consistency throughout the analysis. Data analysis was performed using inductive thematic analysis to provide an authentic representation of how individuals experience and interpret their realities of LEF recovery, grounded in their personal perspectives [28, 29].

Research team and reflexivity

Personal characteristics

The research team comprised experienced healthcare professionals and researchers with diverse expertise. Olufemi Oyewole (OO) is a clinical physiotherapist and researcher with PhD credentials. Lateef Thanni (LT) is an orthopedics consultant, academician, and professor. Adekunle Adebanjo (AA) is a hospital consultant specializing in traumatology. Michael Ogunlana (MO) is a clinical physiotherapist and researcher with PhD qualifications. Abiola Fafolahan (AF) is a clinical physiotherapist with public health interests and biostatistics knowledge. Adesola Odole (AO) is a professor of musculoskeletal physiotherapy with extensive qualitative research experience, and Pragashnie Govender (PG) is a professor of occupational therapy with significant qualitative research expertise. Through this rigorous process, researchers suspended their judgments and prior understanding of recovery post-LEF to ensure that the participant voices emerged [30].

Relationship with participants

OO, LT, and AA were employed in the care setting and directly involved in patient care management, including the care of study participants. This insider perspective provided valuable context while requiring careful attention to potential bias through the bracketing process.

Results

Participant characteristics

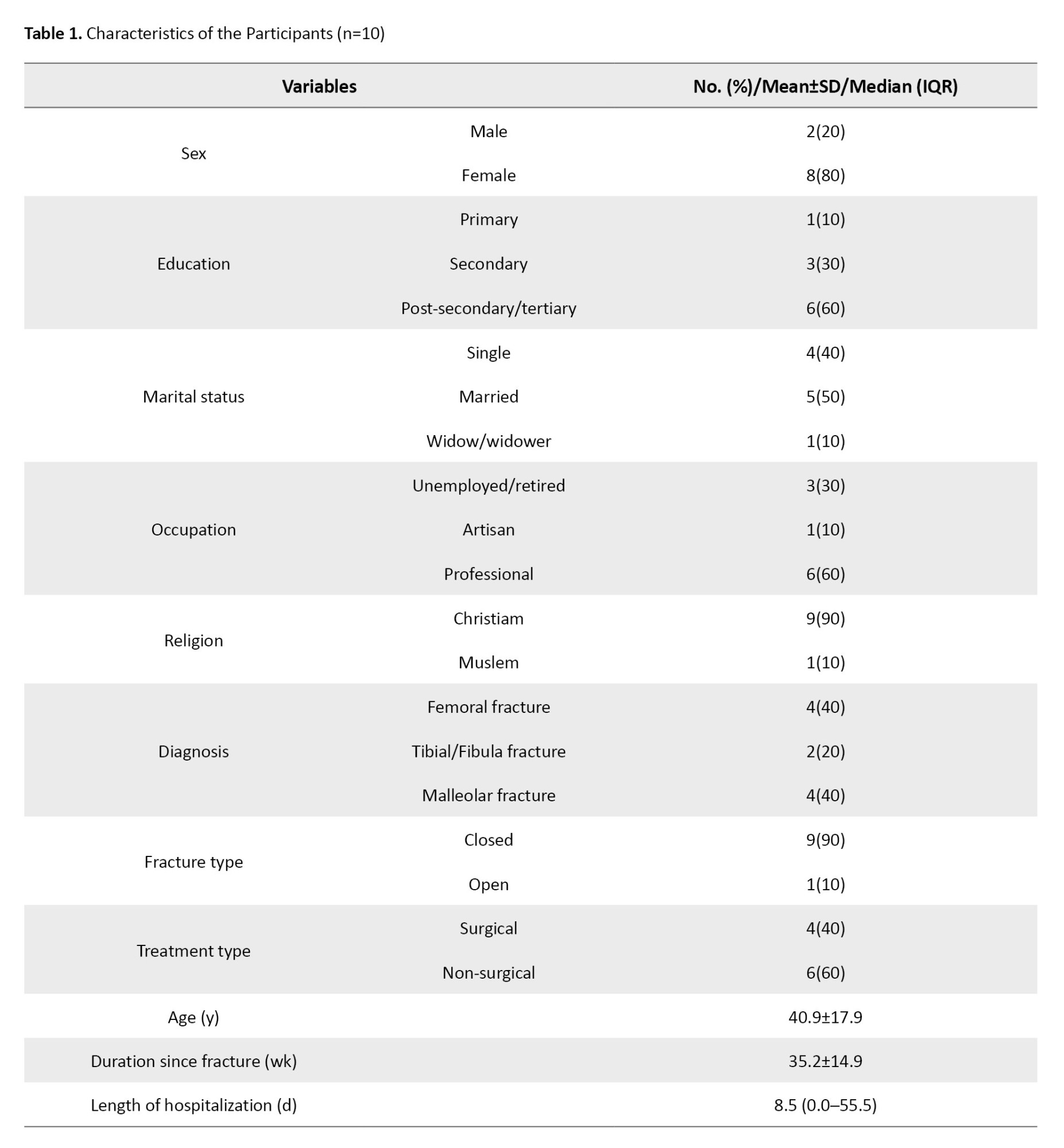

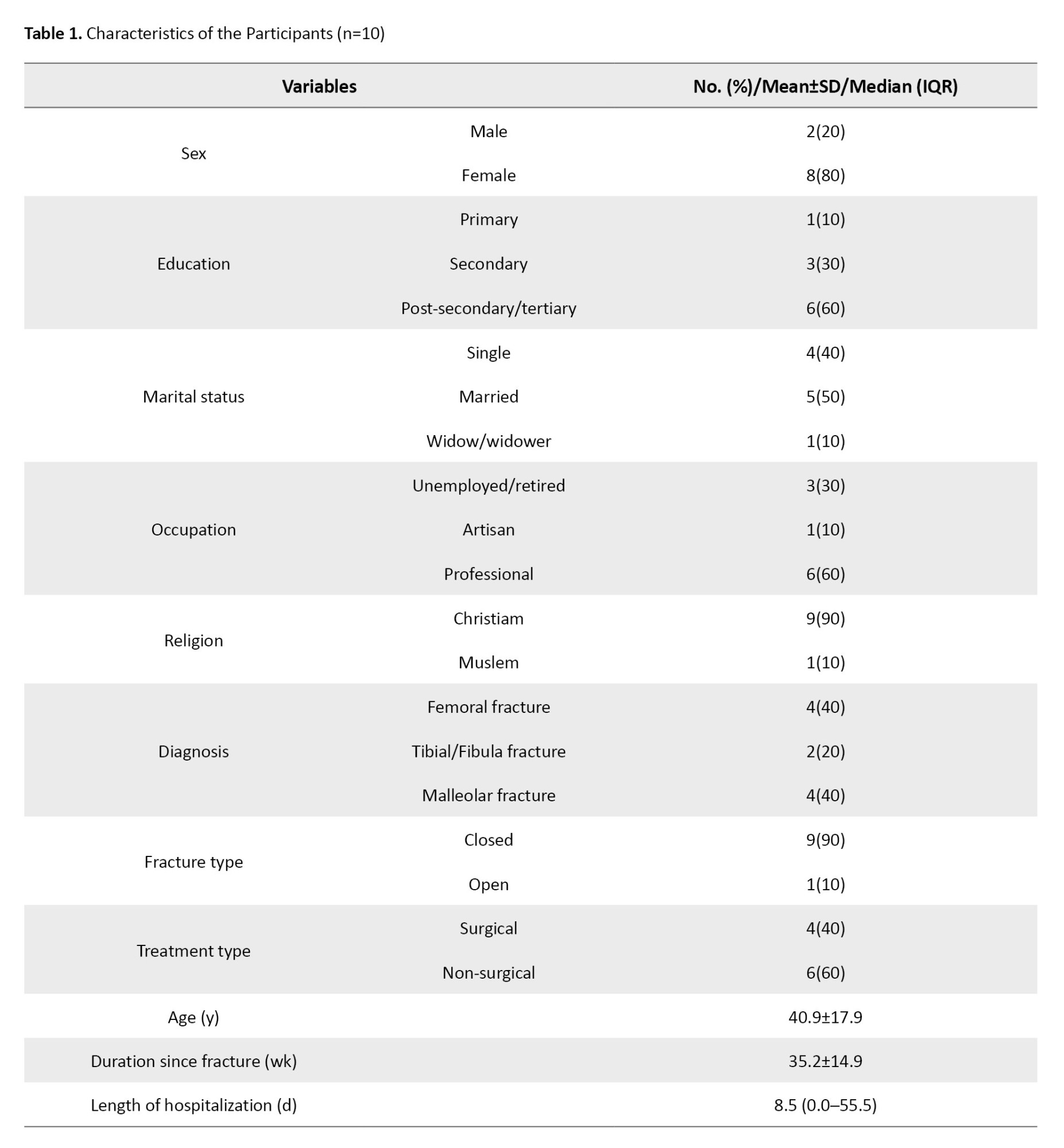

Ten participants contributed their experiences to this study (Table 1).

The majority were females (80%) with tertiary education (60%), married (50%), and a mean age of 40.9±17.9 years. Closed femoral and malleolar fractures were most common (80%), with 60% receiving non-surgical intervention.

Emergent themes

In the contemplative environment of a rehabilitation clinic, participants in this descriptive phenomenological study generously shared their profound, often emotionally charged experiences of recovering from LEF. Their compelling narratives revealed a complex tapestry of physical discomfort, social disruption, and deeply held hopes for complete recovery. Five major themes emerged from the analysis, representing the multifaceted nature of LEF recovery experiences (Table 2).

Discussion

This explorative study provides valuable insights into the lived experiences of Nigerian patients recovering from LEFs, revealing the multifaceted nature of recovery that extends far beyond clinical indicators of bone healing. The findings illuminate critical aspects of patient-centered recovery that have important implications for rehabilitation practice and healthcare service delivery in resource-limited settings.

Pain and functional limitations

Pain emerged as a dominant theme affecting all aspects of participants’ lives, corroborating previous research findings [6, 13, 16, 21]. The persistent nature of pain and its impact on functional activities aligns with established literature indicating that pain can be debilitating, significantly impacting activities of daily living and potentially leading to home-bound or bedridden status if inadequately managed [6, 22]. The participants’ consistent desire for pain-free function underscores the critical need for comprehensive pain management strategies throughout the recovery continuum.

Most participants experienced significant functional limitations, particularly affecting walking capacity. This finding is expected, given the lower extremity’s fundamental role in mobility, and is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that individuals with LEFs experience substantial difficulty performing mobility-related activities [6, 13, 20, 31-33]. The emphasis on walking, gait, and mobility aligns with expert consensus identifying these as core outcome domains for LEF patients [23].

The relationship between mobility restoration and quality of life emerged clearly in participants’ narratives. Mobility limitations led to social isolation, restricted community participation, and broad economic and quality-of-life consequences affecting both patients and family members [6, 11], consistent with previous research identifying walking ability as fundamental to recovery and quality of life among people with LEFs [16]. The concept of mobility as a “bridge to the sense of coherence in everyday life” among individuals with fractures [34] was evident in participants’ descriptions of their recovery priorities.

Social and psychological consequences

The social and psychological impacts of LEFs revealed in this study highlight the complex interplay between physical limitations and psychosocial well-being. Participants experienced significant psychological disturbances, including depression, anxiety, and feelings of being a burden, consistent with previous research [11, 13, 35].

The dependency on family members, while providing necessary support, also created emotional distress and concerns about being a burden to loved ones. This finding suggests that professional social support services, which are often lacking in Nigerian healthcare facilities, could significantly alleviate patient anxiety, fear, and worry while promoting psychological well-being and optimal outcomes [36]. The integration of social welfare services into LEF care pathways represents an essential opportunity for healthcare system improvement.

Cultural and spiritual dimensions

A unique finding of this study relates to participants’ emphasis on spiritual reconnection and worship during recovery. The disruption to religious participation emerged as a significant source of distress, reflecting the profound spiritual nature of Nigerian culture. This finding suggests that healthcare providers should consider spiritual and religious needs as integral components of holistic recovery planning. The role of spiritual resilience as a coping mechanism was evident in participants’ narratives, indicating that spiritual support could be leveraged as a therapeutic resource in the recovery process.

Occupational impact and independence

The disruption to work capacity and income generation represents a critical dimension of LEF impact that extends beyond immediate medical concerns. Participants’ experiences of job loss, reduced work capacity, and economic hardship highlight the need for vocational rehabilitation services and financial support programs. The creative adaptations some participants employed, such as home-based work alternatives, suggest potential intervention strategies that could be integrated into rehabilitation programs.

The desire for functional independence emerged as a paramount recovery goal, reflecting participants’ pre-injury autonomy and self-determination. The over-dependence on others during recovery, while necessary, created additional psychological burden and highlighted the importance of rehabilitation approaches that systematically promote independence while providing essential support.

Healthcare system implications

The findings reveal important gaps in the Nigerian healthcare system’s approach to LEF care. The absence of structured transitions between acute care and community-based rehabilitation, limited access to comprehensive rehabilitation services, and a lack of psychosocial support represent significant opportunities for system improvement. The predominantly out-of-pocket healthcare financing model may exacerbate recovery challenges by limiting access to essential services and increasing financial stress for patients and families.

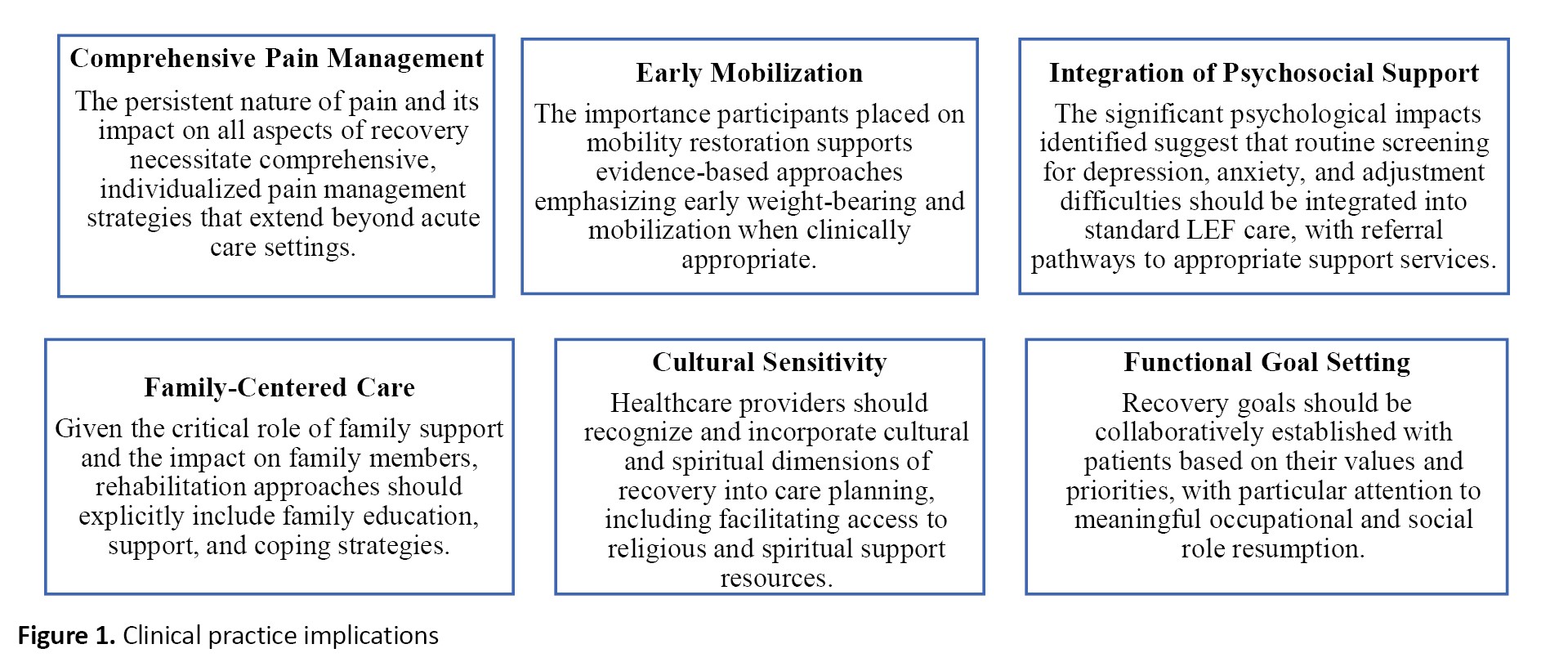

Clinical practice implications

Several important implications for clinical practice emerge from this study (Figure 1).

Conclusion

This study reveals that the lived experience of Nigerian patients following LEFs is characterized by profound, multifaceted impacts extending far beyond clinical indicators of bone healing. Participants’ experiences were marked by persistent mobility limitations, impaired functional capacity affecting daily activities and work participation, social and community participation restrictions, and significant psychological consequences, including depression, anxiety, and concerns about being a burden to others. The recovery priorities identified by participants emphasize the critical importance of pain relief, mobility restoration, functional independence, occupational reengagement, and spiritual reconnection. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive rehabilitation approaches that address not only physical healing but also psychosocial, occupational, and spiritual dimensions of recovery. The study highlights the importance of patient-centered care that incorporates patients’ values, priorities, and cultural context into rehabilitation planning and service delivery. Adequate rehabilitation programs that promote functional independence — highly valued by patients — while addressing psychosocial and spiritual needs may lead to optimal outcomes and enhanced patient satisfaction. Healthcare systems, particularly in resource-limited settings, should consider developing comprehensive care pathways that integrate physical rehabilitation with psychosocial support, vocational services, and spiritual care resources. The findings provide valuable insights for healthcare providers, policymakers, and researchers seeking to improve patient outcomes and experiences after LEFs. Future research should explore intervention strategies based on these patient-identified priorities and examine the effectiveness of comprehensive, culturally sensitive rehabilitation approaches in improving both clinical outcomes and patient-reported recovery measures.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. The single-center design may limit generalizability, although the findings may be transferable to similar healthcare contexts and cultural settings.12 The single-interview approach, conducted 4-16 months post-injury, may have introduced recall bias, although the depth and consistency of participants’ accounts suggest robust data quality. The involvement of some research team members in participants’ clinical care, while providing a valuable insider perspective, required careful attention to potential bias through rigorous bracketing processes. Additionally, the findings reflect experiences within the specific context of the Nigerian healthcare system and cultural setting, which should be considered when applying insights to other contexts.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria (Code: OOUTH/HREC/368/2020AP).

Funding

The paper was extracted from a research project of the Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, approved by Department of Physiotherapy, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, Lateef Olatunji Thanni, Adesola Odole, Michael Ogunlana, and Adekunle Adebanjo; Data collection: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole; Data analysis and interpretation: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, Pragashnie Govender, and Abiola Fafolahan; Drafting of the manuscript: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole and Pragashnie Govender; Manuscript revision and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere gratitude to all participants who generously shared their recovery experiences and insights, which made this research possible. They also acknowledge the support of the healthcare staff at Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital for facilitating participant recruitment and data collection.

References

In Nigeria and many other developing countries, road users face increased risk of traumatic injuries due to inadequate road infrastructure, high traffic volumes, insufficient driver training, poor law enforcement, and lack of physical separation between vehicles and vulnerable road users [1]. Lower extremity bones have been consistently reported as primarily affected in road traffic injuries (RTIs), [2] with tibia/fibula fractures ranking highest, followed by femur fractures in Nigeria [3-5]. The shift toward motorcycle transportation in many rural communities has substantially contributed to these RTIs [2]. The consequences of lower extremity trauma among RTI victims include profound physical suffering and ongoing social and economic costs [6, 7].

The impact of sustaining a lower extremity fracture (LEF) can be life-altering, with prolonged recovery periods that fundamentally affect patients’ quality of life [8]. These impacts encompass delayed return to work, [9] job loss and economic burden [7, 9, 10], disruption of everyday social life and social isolation, [11] family life disruption, [12] sleep deprivation, compromised sense of independence, and diminished psychological well-being [13]. Furthermore, injuries affecting mobility have broad quality of life and economic consequences for both patients and their family members [6, 14-16].

Bone fractures constitute a major global public health concern, accounting for 178 million new cases (78 million involving LEF) in 2019, representing a 33.4% increase since 1990 [17]. The age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates of bone fractures in Nigeria are particularly concerning, with 1100.5 per 100000 and 3190.0 per 100000 population in 2019, demonstrating increases of 5.6% and 4.1% respectively from 1990 [17]. This translates to approximately 193 years lived with disabilities per 100,000 Nigerians in 2019, potentially attributed to increased disability-adjusted life years due to rising RTIs forecasted to double by 2030 in sub-Saharan Africa [1].

Evidence from medical literature suggests that LEF healing typically occurs 3 months post-injury, with patients expected to recover to pre-injury health status within 6 months [14, 18]. However, clinical recovery often does not translate to meaningful functional recovery based on patients’ perceptions and lived experiences. Recent data indicate that Nigerians with LEFs do not return to their pre-injury health status 6 months after LEF [19].

Patient-centered rehabilitation, which prioritizes patients’ perspectives and values, represents one approach to mitigate the burden of LEF. Previous studies exploring the lived experiences of patients with LEF have revealed critical recovery priorities [6, 8, 13, 20-22]. Key areas identified as important include walking, gait and mobility, being able to return to life roles, pain or discomfort, and quality of life [23].

However, extrapolating patients’ lived experiences during recovery may be limited by variations in healthcare systems across countries, particularly when comparing developed nations with lower-middle-income countries like Nigeria. The absence of structured care transitions for Nigerians with LEFs often limits care pathways. In contrast to healthcare systems in developed countries, where patients transition from surgical hospitals to specialized post-acute care facilities [24], Nigerian secondary and tertiary health facilities provide both postoperative care and rehabilitation during prolonged hospital stays. Healthcare financing remains approximately 70% out-of-pocket for most Nigerian patients, with less than 5% of the population having enrolled in health insurance [25].

There is limited information on how Nigerians with LEFs experience the transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home, their recovery experiences, and what matters most to them during their community-based recovery journey. Including the perspectives of Nigerian patients with LEF may improve the quality of care and recovery outcomes [26] while helping to formulate culturally appropriate patient-centered rehabilitation approaches [13]. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of Nigerian patients with LEF, identify what patients consider essential during recovery, and examine how these priorities can inform the evaluation of LEF service quality and patient-centered care approaches.

Patients and Methods

This qualitative study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative (COREQ) research guidelines [27].

Study Design

Theoretical framework

A qualitative, exploratory study was adopted to capture and comprehensively describe the lived experiences of Nigerian patients with LEF during their recovery. The focus was on understanding and describing experiences as they are authentically lived and felt by individuals [28].

Participant Selection

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants representing various types of LEFs, ages, and genders. Ten participants were recruited until data redundancy was achieved, ensuring comprehensive capture of diverse experiences. The inclusion criteria comprised participants who had been discharged from inpatient care, achieved clinical :union: of their LEF, were ≥12 weeks post-injury, and were able to provide informed consent for interviews. Exclusion criteria included patients with non-clinical :union:, <12 weeks post-injury, and those unable to consent to the interview. The sampling process spanned 11 months.

Study setting

In-depth interviews were conducted by the principal investigator in a noise-free, private cubicle (face-to-face) or via telephone to ensure participant comfort and confidentiality. All participants were outpatients at the Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

Data collection

Before interviews, a structured pro forma was used to collect comprehensive sociodemographic and clinical information. Clinical details, including the date of fracture onset, fracture type, length of hospitalization, and treatment modality, were extracted from patients’ hospital records. Sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, education level, and occupation, were systematically documented.

A semi-structured interview guide facilitated consistent yet flexible exploration of experiences across all interviews. Strategic probes were employed to capture detailed information during interviews as appropriate. The interview guide contained carefully constructed questions that elicited participants’ lived experiences during recovery and the factors they considered most important. Participants were asked to describe their typical day and explain how LEF affected their daily lives, including impacts on their mood, walking ability, work capacity, leisure activities, and family relationships. To better understand recovery priorities, participants were asked to identify the most significant factors in their recovery and to compare their daily lives before and after LEF. When necessary, targeted probes were utilized to elicit temporal, procedural, or detailed information.

Interviews were audio-recorded, with reflective annotations to support accurate interpretation of the interview data. Interviews were conducted in either English or Yoruba, depending on participants’ language preferences, and lasted 30 to 45 minutes. The interview guide was professionally translated into Yoruba and back-translated by language experts to ensure data credibility and cultural appropriateness. Trustworthiness in the study was maintained through strategies that included member checking, triangulation during data analysis, an audit trail maintained from conception through to analysis, the research team’s reflexivity, and attempts at thick description in the reporting of the data.

Data analysis

Interviews were recorded using encrypted digital audio recorders and securely downloaded to password-protected laptops accessible only to the lead researcher. All interviews were transcribed verbatim with identifiable information removed to ensure participant confidentiality. Interview transcripts were stored on secure, password-protected devices and pseudonymized using unique study identification numbers. The lead author thoroughly reviewed all transcripts to achieve deep familiarity with the data. Data organization and analysis were completed using ATLAS.ti software, version 24 package. Transcripts were independently coded by two authors, with regular discussion sessions among researchers to ensure agreement, dependability, and consistency throughout the analysis. Data analysis was performed using inductive thematic analysis to provide an authentic representation of how individuals experience and interpret their realities of LEF recovery, grounded in their personal perspectives [28, 29].

Research team and reflexivity

Personal characteristics

The research team comprised experienced healthcare professionals and researchers with diverse expertise. Olufemi Oyewole (OO) is a clinical physiotherapist and researcher with PhD credentials. Lateef Thanni (LT) is an orthopedics consultant, academician, and professor. Adekunle Adebanjo (AA) is a hospital consultant specializing in traumatology. Michael Ogunlana (MO) is a clinical physiotherapist and researcher with PhD qualifications. Abiola Fafolahan (AF) is a clinical physiotherapist with public health interests and biostatistics knowledge. Adesola Odole (AO) is a professor of musculoskeletal physiotherapy with extensive qualitative research experience, and Pragashnie Govender (PG) is a professor of occupational therapy with significant qualitative research expertise. Through this rigorous process, researchers suspended their judgments and prior understanding of recovery post-LEF to ensure that the participant voices emerged [30].

Relationship with participants

OO, LT, and AA were employed in the care setting and directly involved in patient care management, including the care of study participants. This insider perspective provided valuable context while requiring careful attention to potential bias through the bracketing process.

Results

Participant characteristics

Ten participants contributed their experiences to this study (Table 1).

The majority were females (80%) with tertiary education (60%), married (50%), and a mean age of 40.9±17.9 years. Closed femoral and malleolar fractures were most common (80%), with 60% receiving non-surgical intervention.

Emergent themes

In the contemplative environment of a rehabilitation clinic, participants in this descriptive phenomenological study generously shared their profound, often emotionally charged experiences of recovering from LEF. Their compelling narratives revealed a complex tapestry of physical discomfort, social disruption, and deeply held hopes for complete recovery. Five major themes emerged from the analysis, representing the multifaceted nature of LEF recovery experiences (Table 2).

Discussion

This explorative study provides valuable insights into the lived experiences of Nigerian patients recovering from LEFs, revealing the multifaceted nature of recovery that extends far beyond clinical indicators of bone healing. The findings illuminate critical aspects of patient-centered recovery that have important implications for rehabilitation practice and healthcare service delivery in resource-limited settings.

Pain and functional limitations

Pain emerged as a dominant theme affecting all aspects of participants’ lives, corroborating previous research findings [6, 13, 16, 21]. The persistent nature of pain and its impact on functional activities aligns with established literature indicating that pain can be debilitating, significantly impacting activities of daily living and potentially leading to home-bound or bedridden status if inadequately managed [6, 22]. The participants’ consistent desire for pain-free function underscores the critical need for comprehensive pain management strategies throughout the recovery continuum.

Most participants experienced significant functional limitations, particularly affecting walking capacity. This finding is expected, given the lower extremity’s fundamental role in mobility, and is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that individuals with LEFs experience substantial difficulty performing mobility-related activities [6, 13, 20, 31-33]. The emphasis on walking, gait, and mobility aligns with expert consensus identifying these as core outcome domains for LEF patients [23].

The relationship between mobility restoration and quality of life emerged clearly in participants’ narratives. Mobility limitations led to social isolation, restricted community participation, and broad economic and quality-of-life consequences affecting both patients and family members [6, 11], consistent with previous research identifying walking ability as fundamental to recovery and quality of life among people with LEFs [16]. The concept of mobility as a “bridge to the sense of coherence in everyday life” among individuals with fractures [34] was evident in participants’ descriptions of their recovery priorities.

Social and psychological consequences

The social and psychological impacts of LEFs revealed in this study highlight the complex interplay between physical limitations and psychosocial well-being. Participants experienced significant psychological disturbances, including depression, anxiety, and feelings of being a burden, consistent with previous research [11, 13, 35].

The dependency on family members, while providing necessary support, also created emotional distress and concerns about being a burden to loved ones. This finding suggests that professional social support services, which are often lacking in Nigerian healthcare facilities, could significantly alleviate patient anxiety, fear, and worry while promoting psychological well-being and optimal outcomes [36]. The integration of social welfare services into LEF care pathways represents an essential opportunity for healthcare system improvement.

Cultural and spiritual dimensions

A unique finding of this study relates to participants’ emphasis on spiritual reconnection and worship during recovery. The disruption to religious participation emerged as a significant source of distress, reflecting the profound spiritual nature of Nigerian culture. This finding suggests that healthcare providers should consider spiritual and religious needs as integral components of holistic recovery planning. The role of spiritual resilience as a coping mechanism was evident in participants’ narratives, indicating that spiritual support could be leveraged as a therapeutic resource in the recovery process.

Occupational impact and independence

The disruption to work capacity and income generation represents a critical dimension of LEF impact that extends beyond immediate medical concerns. Participants’ experiences of job loss, reduced work capacity, and economic hardship highlight the need for vocational rehabilitation services and financial support programs. The creative adaptations some participants employed, such as home-based work alternatives, suggest potential intervention strategies that could be integrated into rehabilitation programs.

The desire for functional independence emerged as a paramount recovery goal, reflecting participants’ pre-injury autonomy and self-determination. The over-dependence on others during recovery, while necessary, created additional psychological burden and highlighted the importance of rehabilitation approaches that systematically promote independence while providing essential support.

Healthcare system implications

The findings reveal important gaps in the Nigerian healthcare system’s approach to LEF care. The absence of structured transitions between acute care and community-based rehabilitation, limited access to comprehensive rehabilitation services, and a lack of psychosocial support represent significant opportunities for system improvement. The predominantly out-of-pocket healthcare financing model may exacerbate recovery challenges by limiting access to essential services and increasing financial stress for patients and families.

Clinical practice implications

Several important implications for clinical practice emerge from this study (Figure 1).

Conclusion

This study reveals that the lived experience of Nigerian patients following LEFs is characterized by profound, multifaceted impacts extending far beyond clinical indicators of bone healing. Participants’ experiences were marked by persistent mobility limitations, impaired functional capacity affecting daily activities and work participation, social and community participation restrictions, and significant psychological consequences, including depression, anxiety, and concerns about being a burden to others. The recovery priorities identified by participants emphasize the critical importance of pain relief, mobility restoration, functional independence, occupational reengagement, and spiritual reconnection. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive rehabilitation approaches that address not only physical healing but also psychosocial, occupational, and spiritual dimensions of recovery. The study highlights the importance of patient-centered care that incorporates patients’ values, priorities, and cultural context into rehabilitation planning and service delivery. Adequate rehabilitation programs that promote functional independence — highly valued by patients — while addressing psychosocial and spiritual needs may lead to optimal outcomes and enhanced patient satisfaction. Healthcare systems, particularly in resource-limited settings, should consider developing comprehensive care pathways that integrate physical rehabilitation with psychosocial support, vocational services, and spiritual care resources. The findings provide valuable insights for healthcare providers, policymakers, and researchers seeking to improve patient outcomes and experiences after LEFs. Future research should explore intervention strategies based on these patient-identified priorities and examine the effectiveness of comprehensive, culturally sensitive rehabilitation approaches in improving both clinical outcomes and patient-reported recovery measures.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. The single-center design may limit generalizability, although the findings may be transferable to similar healthcare contexts and cultural settings.12 The single-interview approach, conducted 4-16 months post-injury, may have introduced recall bias, although the depth and consistency of participants’ accounts suggest robust data quality. The involvement of some research team members in participants’ clinical care, while providing a valuable insider perspective, required careful attention to potential bias through rigorous bracketing processes. Additionally, the findings reflect experiences within the specific context of the Nigerian healthcare system and cultural setting, which should be considered when applying insights to other contexts.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria (Code: OOUTH/HREC/368/2020AP).

Funding

The paper was extracted from a research project of the Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, approved by Department of Physiotherapy, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, Lateef Olatunji Thanni, Adesola Odole, Michael Ogunlana, and Adekunle Adebanjo; Data collection: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole; Data analysis and interpretation: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole, Pragashnie Govender, and Abiola Fafolahan; Drafting of the manuscript: Olufemi Oyeleye Oyewole and Pragashnie Govender; Manuscript revision and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere gratitude to all participants who generously shared their recovery experiences and insights, which made this research possible. They also acknowledge the support of the healthcare staff at Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital for facilitating participant recruitment and data collection.

References

- Marquez PV, Farrington JL. The challenge of non-communicable diseases and road traffic injuries in sub-Saharan Africa. An overview. Washington: The World Bank; 2013. [Link]

- Martins RS, Saqib SU, Gillani M, Sania SRT, Junaid MU, Zafar H. Patterns of traumatic injuries and outcomes to motorcyclists in a developing country: A cross-sectional study. Traffic Inj Prev. 2021; 22(2):162-6. [DOI:10.1080/15389588.2020.1856374] [PMID]

- Owoola AM, Thanni LOA. Epidemiology and outcome of limb fractures in Nigeria: A hospital based study. Nigerian J Orthop Trauma. 2012;11(2):97-101. [DOI:10.4314/njotra.v11i2]

- Enweluzo GO, Giwa SO, Obalum DC. Pattern of extremity injuries in polytrauma in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2008; 15(1):6-9. [DOI:10.4103/1117-1936.180913] [PMID]

- Babalola OM, Salawu ON, Ahmed BA, Ibraheem GH, Olawepo A, Agaja SB. Epidemiology of traumatic fractures in a tertiary health center in Nigeria. J Orthop Traumatol Rehabil. 2018; 10(2):87-9. [DOI:10.4103/jotr.jotr_35_16]

- Kohler RE, Tomlinson J, Chilunjika TE, Young S, Hosseinipour M, Lee CN. "Life is at a standstill" quality of life after lower extremity trauma in Malawi. Qual Life Res. 2017; 26(4):1027-35. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-016-1431-2] [PMID]

- Levy JF, Reider L, Scharfstein DO, Pollak AN, Morshed S, Firoozabadi R, et al. The 1-year economic impact of work productivity loss following severe lower extremity trauma. J Bone Joint Surg. 2022; 104(7):586-93. [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.21.00632] [PMID]

- Rees S, Tutton E, Achten J, Bruce J, Costa ML. Patient experience of long-term recovery after open fracture of the lower limb: A qualitative study using interviews in a community setting. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(10):e031261. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031261] [PMID]

- Masterson S, Laubscher M, Maqungo S, Ferreira N, Held M, Harrison WJ, et al. Return to work following intramedullary nailing of lower-limb long-bone fractures in South Africa. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023; 105(7):518-26. [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.22.00478] [PMID]

- Mody KS, Wu HH, Chokotho LC, Mkandawire NC, Young S, Lau BC, et al. The Socioeconomic consequences of femoral shaft fracture for patients in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2023; 35(3):141-50. [DOI:10.4314/mmj.v35i3.2] [PMID]

- Zare Z, Ghane G, Shahsavari H, Ahmadnia S, Ghiyasvandian S. Social life after hip fracture: A qualitative study. J Patient Exp. 2024; 11:23743735241241174. [DOI:10.1177/23743735241241174] [PMID]

- Segevall C, Söderberg S. Participating in the illness journey: Meanings of being a close relative to an older person recovering from hip fracture-A phenomenological hermeneutical study. Nurs Rep. 2022; 12(4):733-46. [DOI:10.3390/nursrep12040073] [PMID]

- McKeown R, Kearney RS, Liew ZH, Ellard DR. Patient experiences of an ankle fracture and the most important factors in their recovery: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(2):e033539. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033539] [PMID]

- Sluys KP, Shults J, Richmond TS. Health related quality of life and return to work after minor extremity injuries: A longitudinal study comparing upper versus lower extremity injuries. Injury. 2016; 47(4):824-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2016.02.019] [PMID]

- de Andrade Fonseca M, Cordeiro Matias AG, de Lourdes de Freitas Gomes M, Almeida Matos M. Impact of lower limb fractures on the quality of life. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2019; 21(1):33-40. [DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0013.1078] [PMID]

- Schade AT, Sibande W, Kumwenda M, Desmond N, Chokotho L, Karasouli E, et al. "Don't rush into thinking of walking again": Patient views of treatment and disability following an open tibia fracture in Malawi. Wellcome Open Res. 2022; 7:204. [DOI:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18063.1] [PMID]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022; 9(2):137-50. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3] [PMID]

- Marsh JL, McKinley T, Dirschl D, Pick A, Haft G, Anderson DD, et al. The sequential recovery of health status after tibial plafond fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010; 24(8):499-504. [DOI:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181c8ad52] [PMID]

- Oyewole OO, Thanni LO, Adebanjo AA. Recovery in selected health status after lower limb fractures. Paper presented as: World Physiotherapy Congress 2021. 2021 April 11; Dubai, UAE. [Link]

- Bruun-Olsen V, Bergland A, Heiberg KE. "I struggle to count my blessings": Recovery after hip fracture from the patients' perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2018; 18(1):18. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-018-0716-4] [PMID]

- Griffiths F, Mason V, Boardman F, Dennick K, Haywood K, Achten J, et al. Evaluating recovery following hip fracture: A qualitative interview study of what is important to patients. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(1):e005406. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005406] [PMID]

- Pearson NA, Tutton E, Gwilym SE, Joeris A, Grant R, Keene DJ, et al. Understanding patient experience of distal tibia or ankle fracture: A qualitative systematic review. Bone Jt Open. 2023; 4(3):188-97. [DOI:10.1302/2633-1462.43.BJO-2022-0115.R1] [PMID]

- Aquilina AL, Claireaux H, Aquilina CO, Tutton E, Fitzpatrick R, Costa ML, et al. Development of a core outcome set for open lower limb fracture. Bone Joint Res. 2023; 12(4):294-305. [DOI:10.1302/2046-3758.124.BJR-2022-0164.R2] [PMID]

- Riester MR, Beaudoin FL, Joshi R, Hayes KN, Cupp MA, Berry SD, et al. Evaluation of post-acute care and one-year outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with hip fractures: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2023; 21(1):232. [DOI:10.1186/s12916-023-02958-9] [PMID]

- Ipinnimo TM, Durowade KA, Afolayan CA, Ajayi PO, Akande TM. The Nigeria national health insurance authority act and its implications towards achieving universal health coverage. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2022; 29(4):281-7. [DOI:10.4103/npmj.npmj_216_22] [PMID]

- Karlsson Å, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Lindelöf N. Older adults' perspectives on rehabilitation and recovery one year after a hip fracture - A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022; 22(1):423. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03119-y] [PMID]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19(6):349-57. [DOI:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042] [PMID]

- Sundler AJ, Lindberg E, Nilsson C, Palmér L. Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nurs Open. 2019; 6(3):733-9. [DOI:10.1002/nop2.275] [PMID]

- Giorgi AP, Giorgi B. Phenomenological Psychology. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2008. [DOI:10.4135/9781848607927.n10]

- Thomas SP, Sohn BK. From uncomfortable squirm to self-discovery: A phenomenological analysis of the bracketing experience. Int J Qual Methods. 2023; 22:16094069231191636. [DOI:10.1177/16094069231191635]

- Allen Ingabire JC, Stewart A, Uwakunda C, Mugisha D, Sagahutu JB, Urimubenshi G, et al. Factors affecting social integration after road traffic orthopaedic injuries in Rwanda. Front Rehabil Sci. 2024; 4:1287980. [DOI:10.3389/fresc.2023.1287980] [PMID]

- Ko YJ, Lee JH, Baek SH. Discharge transition experienced by older Korean women after hip fracture surgery: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021; 20(1):112. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-021-00637-9] [PMID]

- Phelps EE, Tutton E, Griffin X, Baird J; TrAFFix research collaborators. A qualitative study of patients' experience of recovery after a distal femoral fracture. Injury. 2019; 50(10):1750-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2019.07.021] [PMID]

- Vestøl I, Debesay J, Bergland A. Mobility-A bridge to sense of coherence in everyday life: Older patients' experiences of participation in an exercise program during the first 3 weeks after hip fracture surgery. Qual Health Res. 2021; 31(10):1823-32. [DOI:10.1177/10497323211008848] [PMID]

- Sandberg M, Ivarsson B, Johansson A, Hommel A. Experiences of patients with hip fractures after discharge from hospital. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2022; 46:100941. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijotn.2022.100941] [PMID]

- Majewski-Schrage T, Evans TA, Snyder KR. Identifying meaningful patient outcomes after lower extremity injury, part 1: Patient experiences during recovery. J Athl Train. 2019; 54(8):858-68. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-232-18]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Rehabilitation management

Received: 2025/09/3 | Accepted: 2025/10/21 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2025/09/3 | Accepted: 2025/10/21 | Published: 2025/03/2