Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Moradazar S, Hatamizadeh N, Loni E, Hosseinzadeh S. Rapid Assessment of Current Employment, Job Preferences, and Capabilities of People With Sensory-motor Disabilities. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-324-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-324-en.html

1- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,nikta_h@yahoo.com

3- Clinical Research Development Center, Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Clinical Research Development Center, Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 547 kb]

(105 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (310 Views)

Full-Text: (55 Views)

Introduction

It is estimated that about 1.3 billion people with disabilities live around the world [1], 55% of whom are of working age [2].

In developing countries, the rate of unemployment is 80–90% among working-aged people with disabilities [3]. Unfortunately, the gap in the employment of people with and without disabilities has not decreased over the past decade [4]. According to a study by Bonaccio et al. on the participation of people with disabilities throughout the employment cycle, one of the main reasons for the lack of jobs among these people is a pessimistic belief in their ability to perform work-related tasks [5].

Obviously, the job of people with disabilities must be consistent with their physical abilities. Otherwise, they cannot handle their work and would feel rejected [6, 7]. Thus, job matching plays an integral role in the integration of this group into the workforce [8]. In facilitating the employment of job seekers with disabilities, the first step is to obtain information about their knowledge, skills, and interests, and to identify employers’ needs and interests to match them accordingly [9]. Anand and Sevak indicated that people with sensory, motor, or mental disabilities whose work-related tasks matched their capabilities reported more long-term employment than the others [10].

The engagement of people with disabilities in the workforce has received special attention in the government’s macro-planning. Providing vocational rehabilitation and enhancing the job-readiness of people with disabilities are among the missions of welfare organizations in many countries [11], including Iran. Such actions aim to help these people become employed and enjoy independent lives.

According to a study by the Welfare Organization, using cluster sampling, about 11.5% of Iran’s population lives with disabilities, and the prevalence rates of motor, visual, and hearing impairments are 6.6%, 3.6%, and 1.8%, respectively [12]. The city of Namin is located in Ardabil Province in northwest Iran. The prevalence rate of disability in this province is 12.7%, which is slightly higher than the mean rate of the country. Based on the 2016 census, the total population of this city is 13659 [13]. The relative prevalence of motor, visual, and hearing impairments among people with disabilities in Ardabil province is 42%, 19%, and 15%, respectively [12].

In general, 163 people with sensory and/or motor disabilities of working age (16–60 years old) were enrolled in the Welfare Organization of Namin, in 2022 [1]. This organization provided vocational rehabilitation services to people with disabilities who registered their names and sought work. Although data were available on the physical, mental, social, and environmental status of the registered people, there was little information about their job interests, capabilities, and skills. It should be noted that this information is mandatory for running readiness programs for people with sensory and motor disabilities, to facilitate their participation in popular jobs in their region. Accordingly, the present study aims to estimate the current employment status, job preferences, and capabilities of people with sensory-motor disabilities in Namin.

Materials and Methods

This survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Using the census method, all 163 people with sensory and/or motor disabilities aged between 16 and 60 years who were registered in the Welfare Organization of Namin were invited to join the study. The survey questionnaire was developed by the research team and subsequently modified several times in terms of format, question wording, and answer choices. The opinions of university colleagues working in different departments (i.e. rehabilitation management, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, ergonomics, rehabilitation engineering, health professionals working in the vocational rehabilitation office of welfare organizations, and people with disabilities of working age) were collected for this purpose. The resulting questionnaire comprised 39 questions and was divided into four parts.

The first part was composed of 5 questions about the participants’ demographic characteristics. Items in the second one asked about one’s current job, job interests, and skills (questions 6–23). This part began with questions about their work experiences and technical skills, as well as the jobs of others around them (e.g. relatives and acquaintances). These questions were icebreakers and were intended to help the person focus on the subject of the questionnaire. The third part covered questions on eight general fields of the job market and common jobs in Namin (questions 24–34). In each field, the work areas were named, and the participants were asked about their level of interest in each job as well as the levels of their technical skills and physical capabilities for engaging in the work that they were interested in. The fourth part consisted of items related to the minimum salary they expected, types of disabilities they had, and probable use of assistive devices (questions 35–39).

The questionnaire was completed by 12 people with disabilities to mention their opinions about clarity and ease of answering by checkmark (yes/no) for each question, and to write their suggestions in case any question was unclear or difficult to answer. The respondents confirmed clarity and ease of answering the questions. The content validity of the survey questionnaire was examined using the Lawshe method, and the content validity index was 0.97. In addition, the questionnaire’s reliability was assessed using the test-re-test method. Kappa reliability coefficients for the questionnaire’s items ranged from 0.84 to 0.96.

SPSS software, version 23, was used for data analysis. Moreover, the chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to determine the relationship between individual variables and job interests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

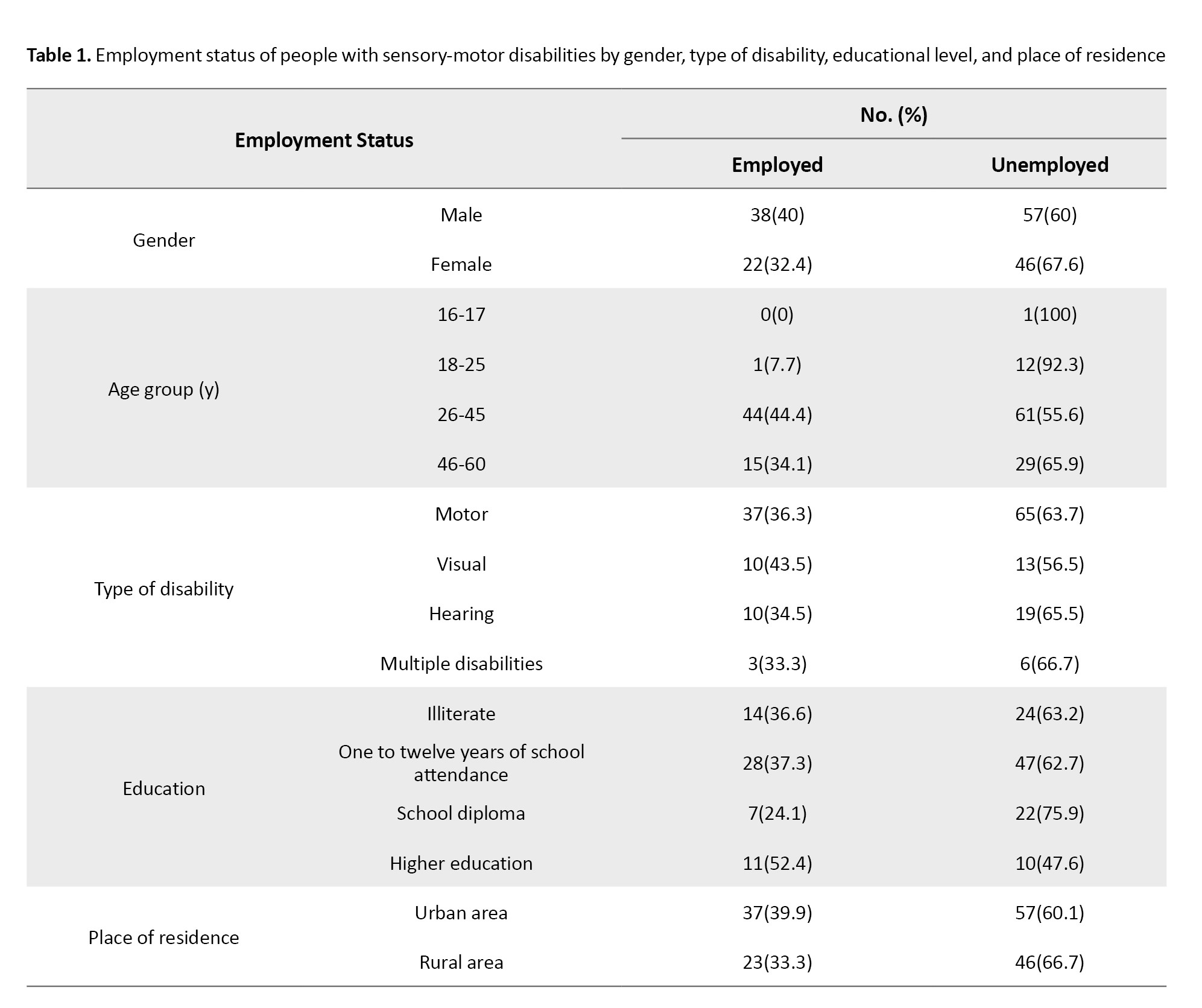

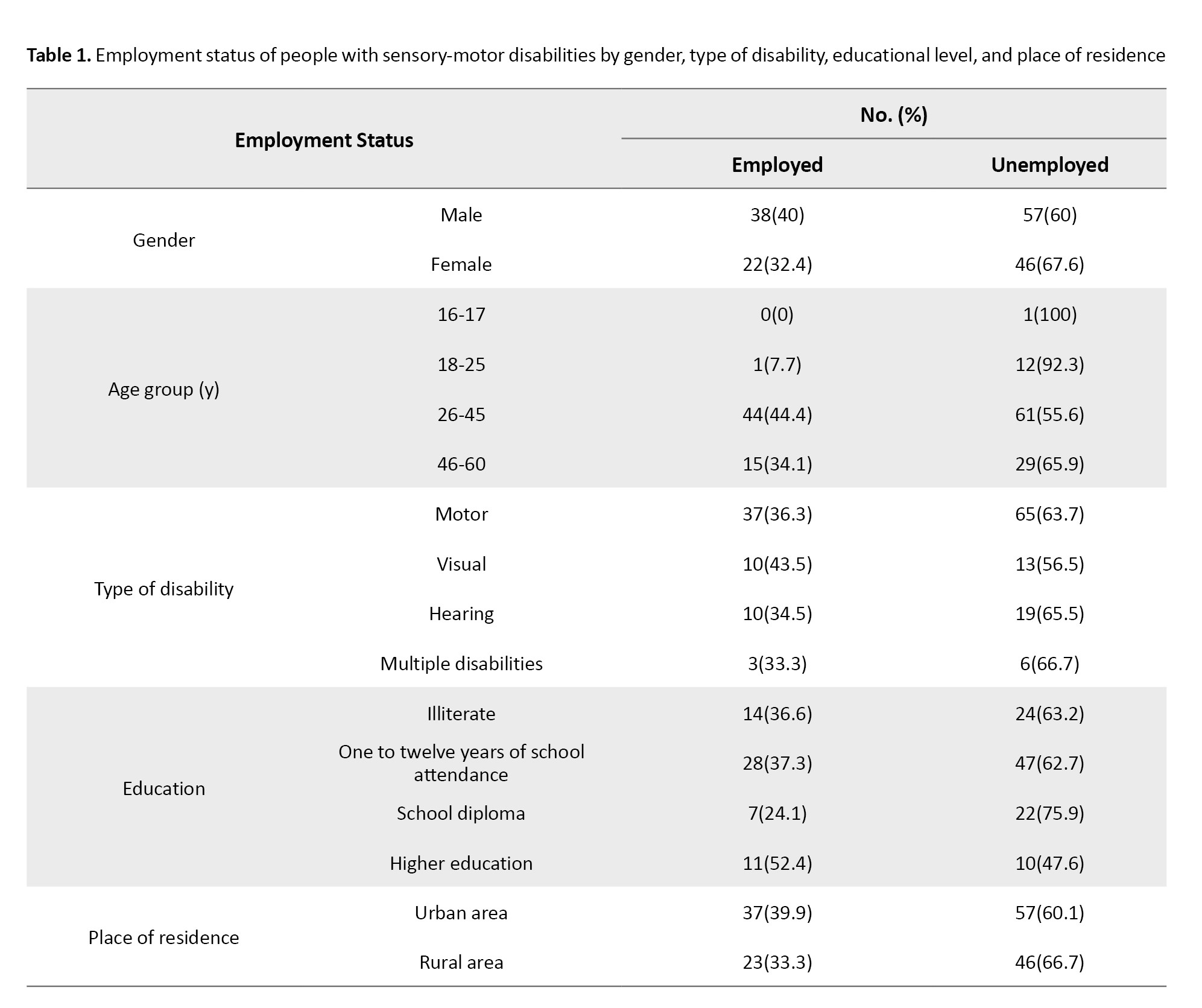

A total of 163 people with sensory and motor disabilities participated in this study. The male-to-female ratio was 95:68. More than 61% of the participants were married, while the remaining participants were single. Table 1 presents the employment status of people with sensory and motor disabilities by gender, disability type, educational level, and place of residence.

Based on the results, the employment rate among males (40%) was higher than among females (32.4%). In addition, the frequency of employment of people with motor and visual disabilities was higher (36.3% and 43.5%) than that of people with hearing and multiple disabilities (34.5% and 33.3%). The highest employment rate (52.4%) was among people with higher education, whereas people with a diploma had the lowest employment rate (24.1%). Finally, the employment rate was higher among people aged 26–45 than among younger and older people.

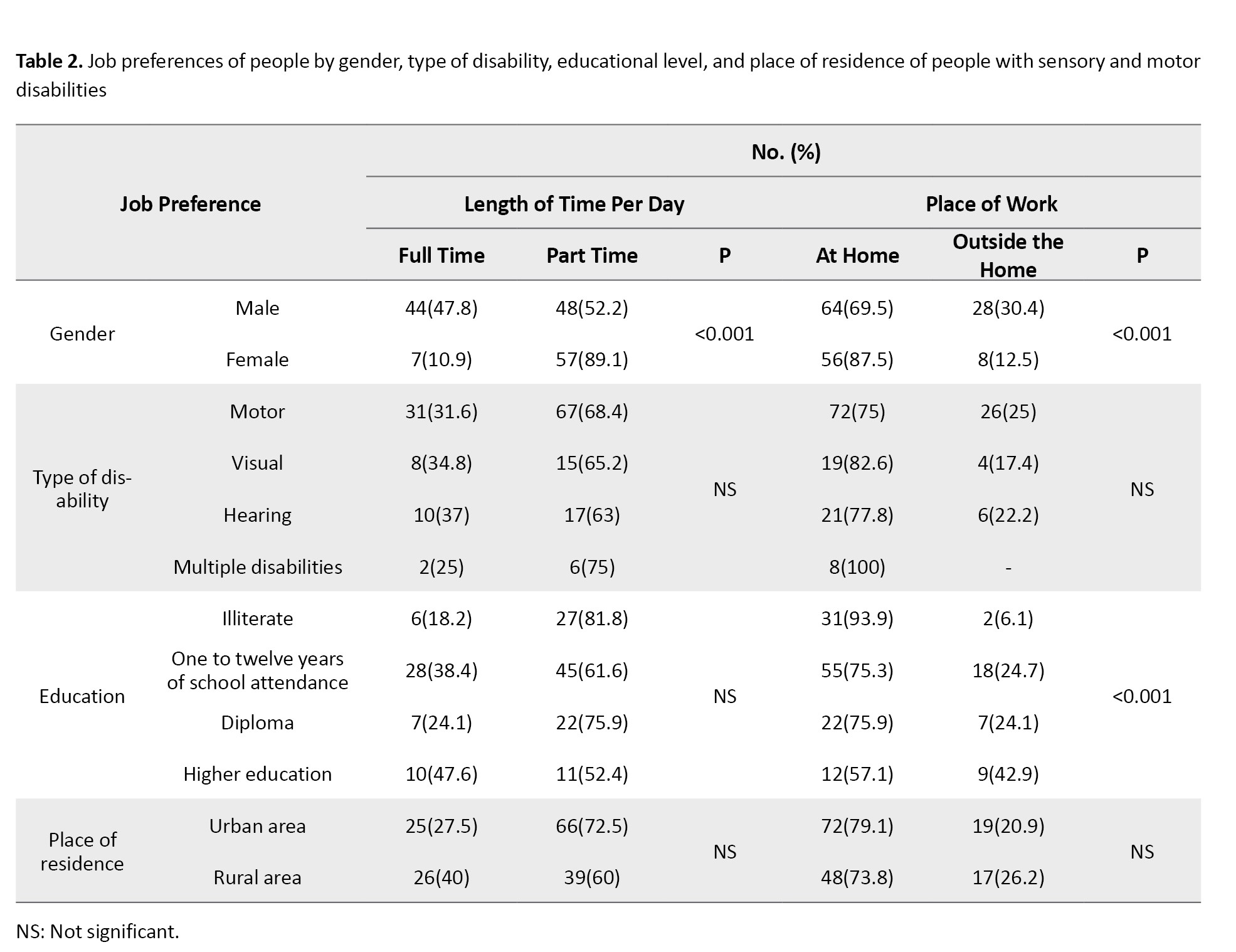

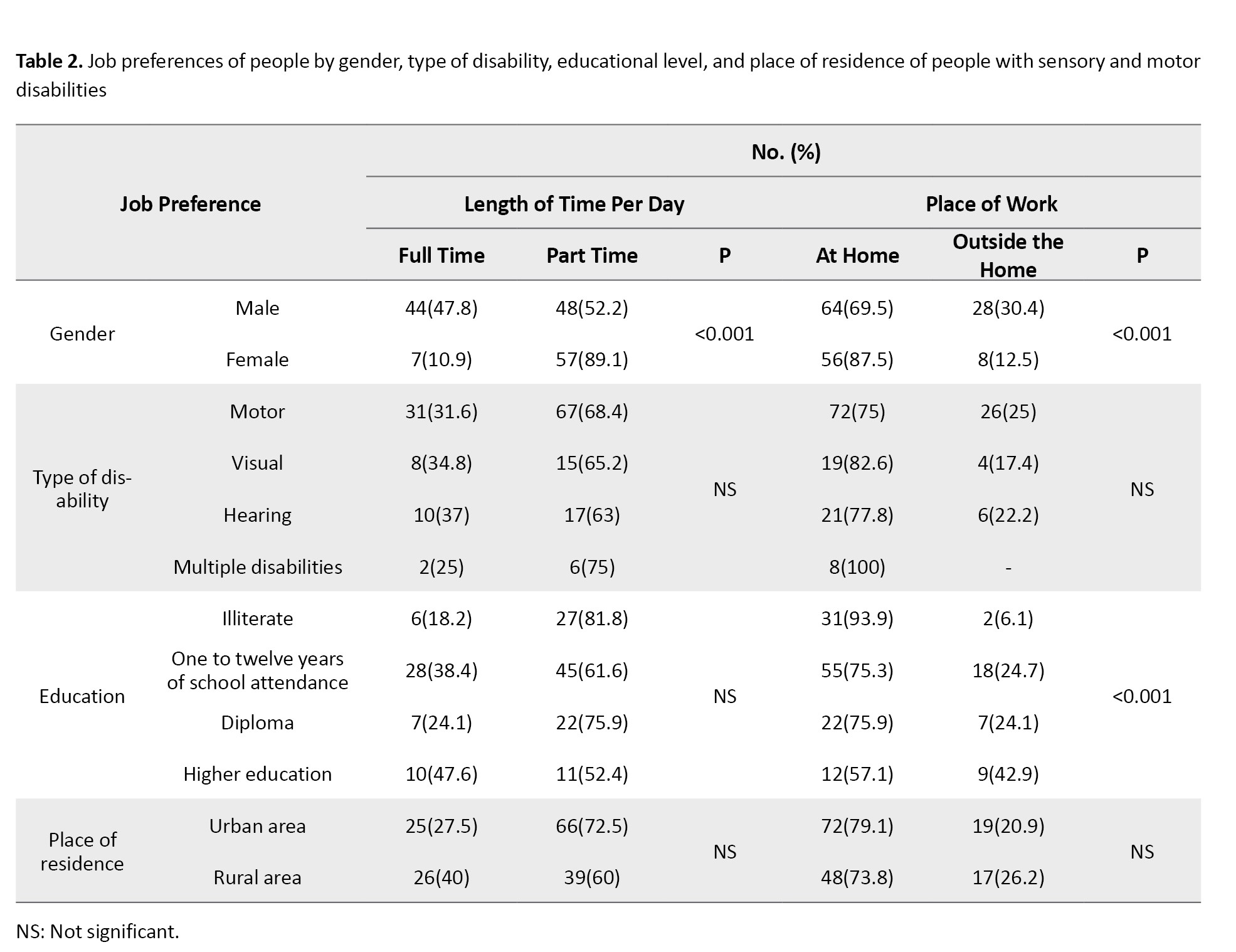

It is noteworthy that all participants were interested in work engagement, with only 7(3.5%) not interested in employment. Table 2 provides data on the job preferences of people interested in work, including preferred time and place of work, by gender, type of disability, educational level, and place of residence.

The results revealed that 32.7% of people were interested in full-time work; this interest was more pronounced among men (47.8%) than among women (10.9%) (P<0.001).

Moreover, men (30.4%) were more interested in working outside the home than women (12.5%), and people with higher education (42.9%) were more interested than those with a diploma or lower educational levels (P<0.001).

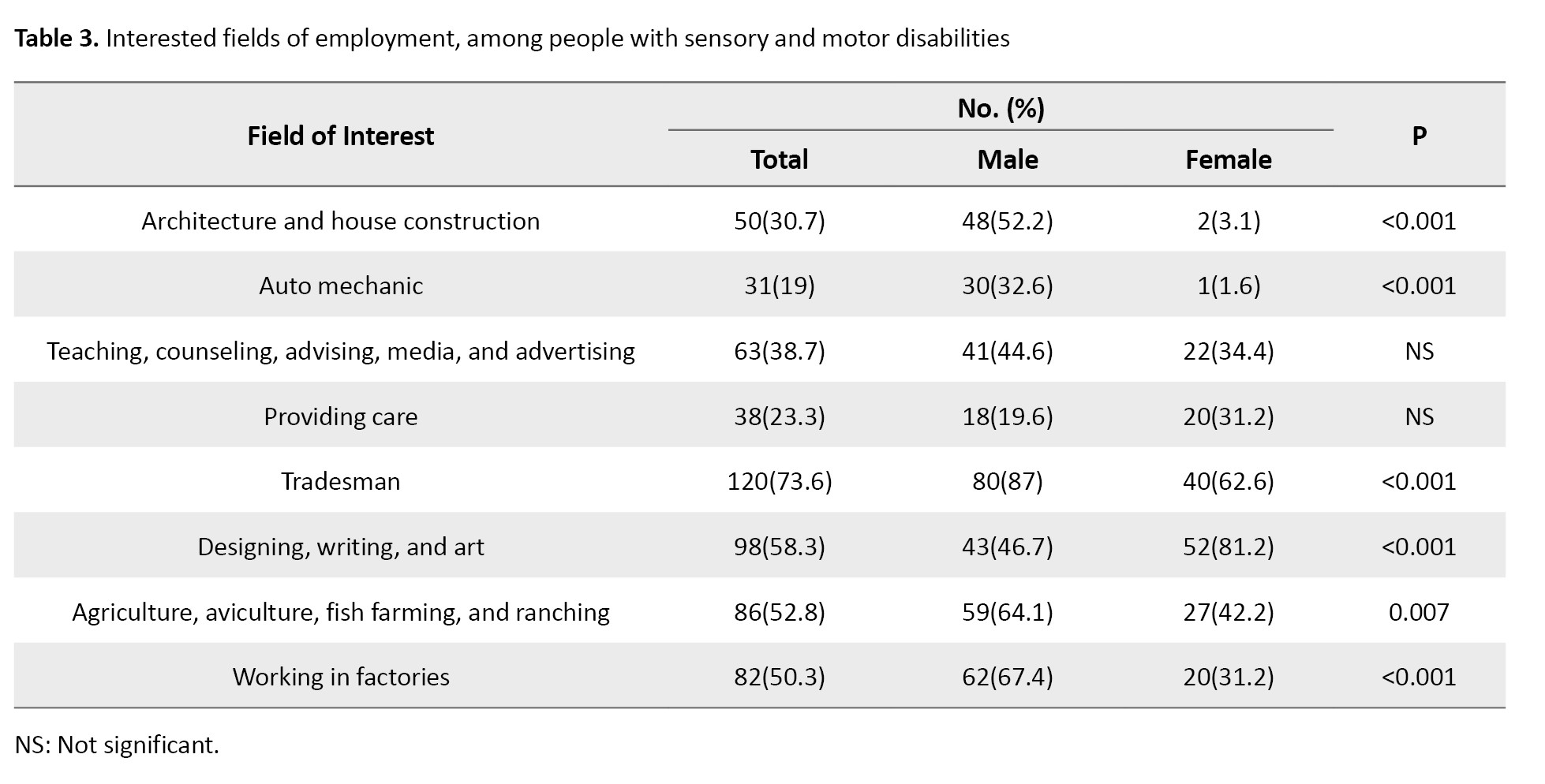

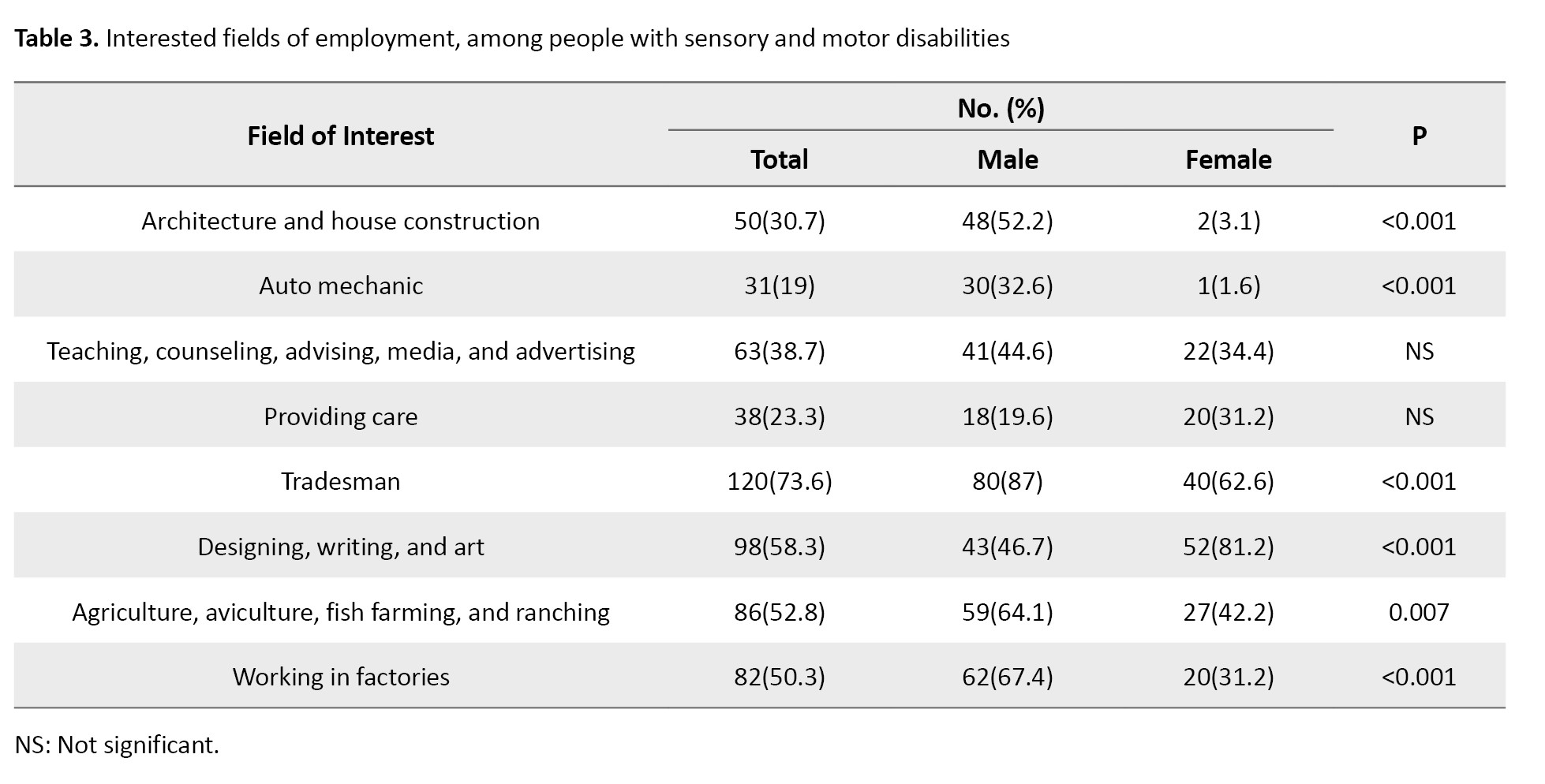

Each participant was asked to mark one or more fields of employment that they were interested in. Table 3 lists the fields of interest of the 156 people with disabilities who have stated their willingness to be employed.

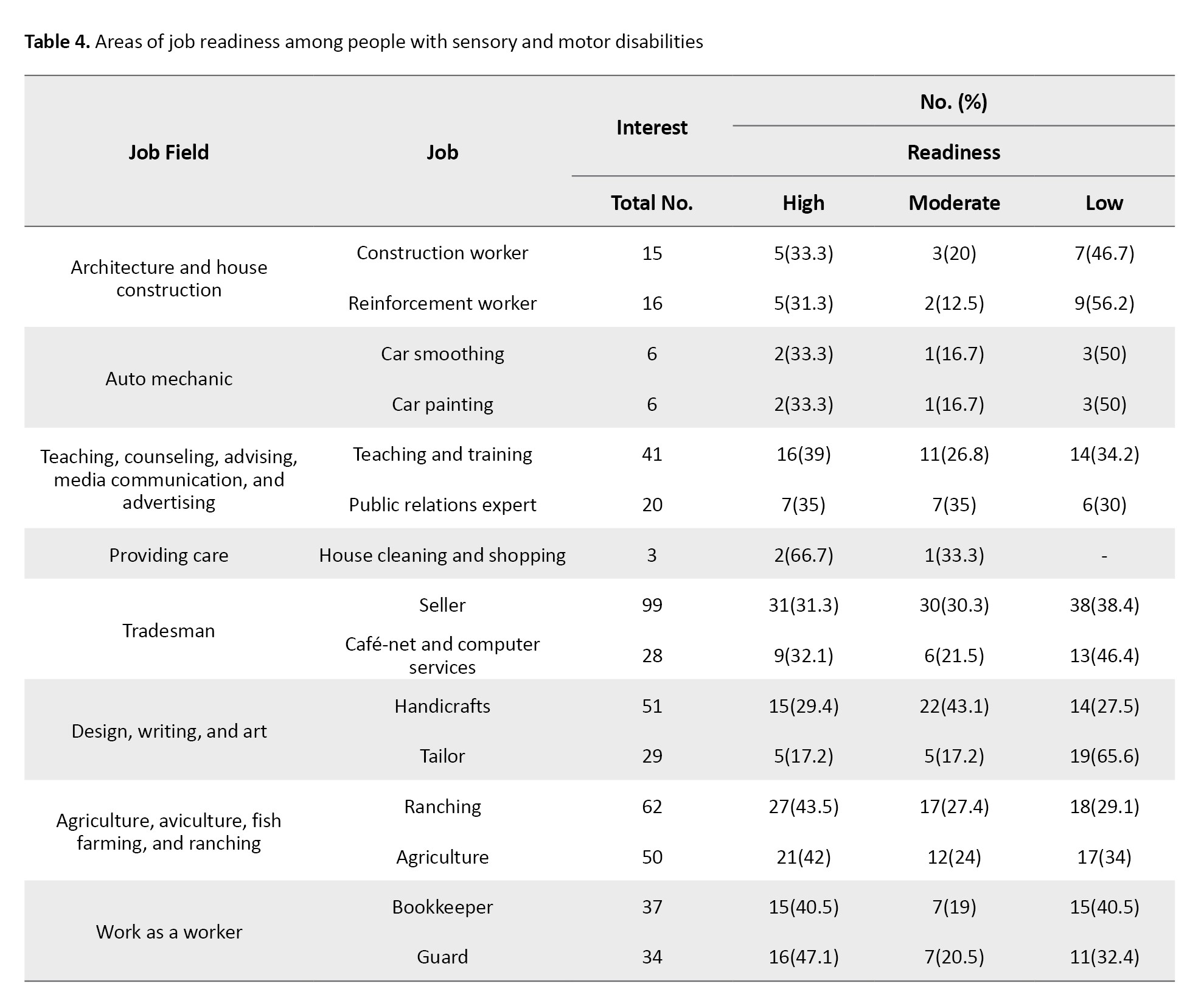

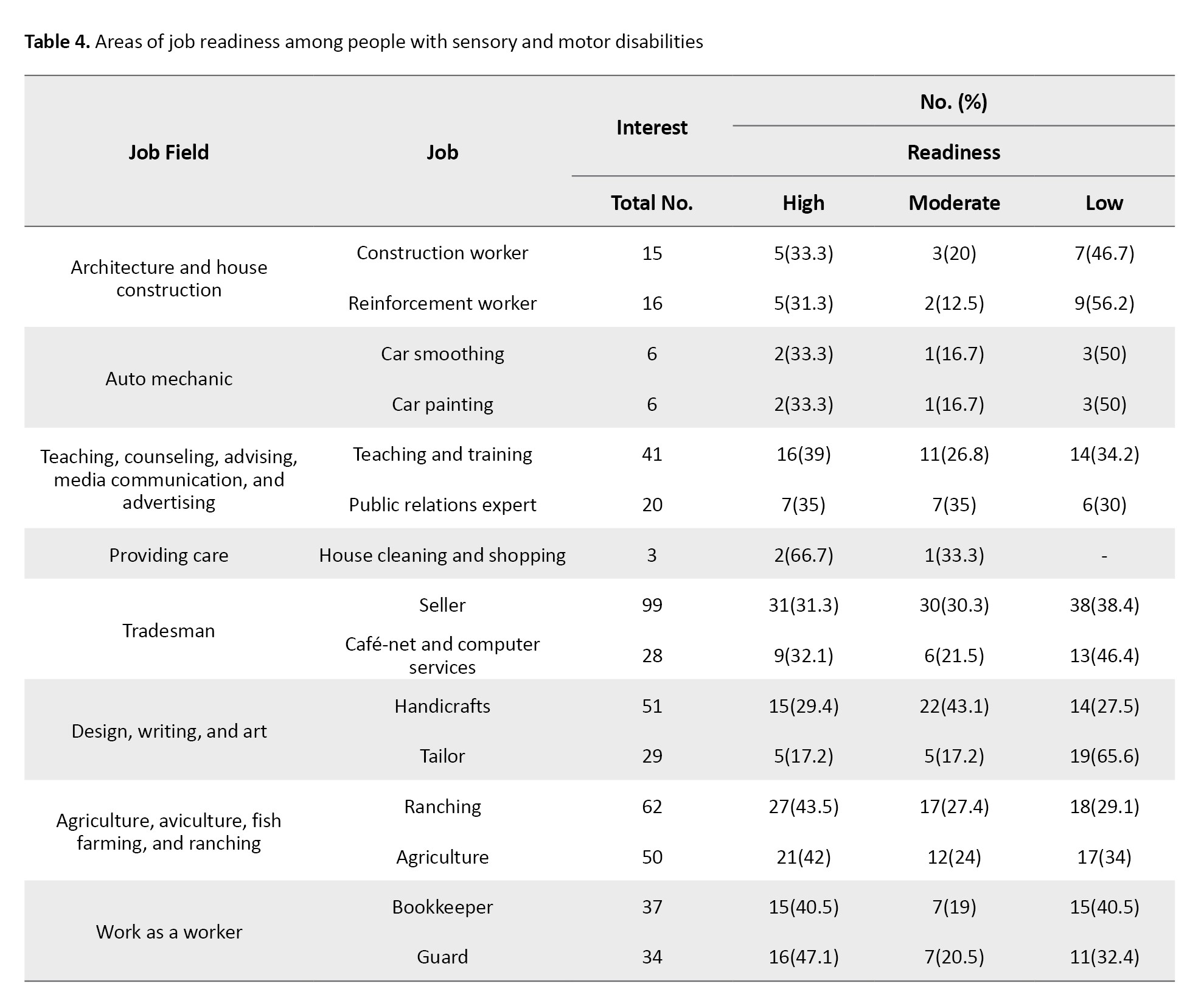

Nearly 73.6% of people with sensory and motor disabilities expressed their interest in trading jobs, and more than 50% were interested in working in each of the fields of “design, writing, and art”, “agriculture, aviculture, fish farming, and ranching”, and “working in factories”. The areas of job interest and related job readiness are presented in Table 4.

Selling, handicraft design, and teaching and training jobs, as well as ranching and agriculture, were the jobs of choice for more people than other jobs, and readiness for being a seller or doing ranching were the most frequently reported fields of work (Table 4).

Discussion

This section is arranged into two parts: “Current employment status and career interests” and “capabilities of people with sensory and motor disabilities”.

Current employment status

The illiteracy rate in the general population at working age was 12.9% among males and 26.3% among females, based on the 2016 Census [13]. According to the present study, these rates were 14.7% and 35.3% among males and females with sensory and motor disabilities, respectively. According to the census, the unemployment rate was 14%, which was 4 times lower than that of people with sensory and motor disabilities, which was found to be 63% in this study. These figures highlight the need for action to reduce gaps between people with disabilities, especially females with disabilities, and others, according to educational levels, skills training, and employment.

Our findings revealed that the employment rate among people with higher educational levels (53%) was higher than that among those with high school levels (34%). Anand Sevak reported the same result in the three states of Mississippi, New Jersey, and Ohio in the USA [10].

In the present study, among people with disabilities, the employment rate was higher in the middle-aged group (26–45 years old) than in the younger and older groups. This reverse U-shape curve is similar to that of the employment rate in the general population [14].

In this study, only 42% of people with sensory and motor disabilities used any assistive technology (AT). Considering that using AT would help people with disabilities become independent in different aspects of life and improve job readiness, assessing people’s awareness of ATs that would be useful to them and conducting AT needs assessments would provide valuable information for planning AT provision for people with disabilities.

Job preferences of people with sensory-motor disabilities

Some employers believe that people with disabilities do not want to work at all, which might negatively affect their decision to hire people with disabilities [15]. Based on the findings of the present study, 96% of working-age people with sensory and motor disabilities desired to work in Namin. This result indicates that the above-mentioned belief of employers is not right, which is in line with the results of a survey in the United States (2011), showing that 80% of people with disabilities were eager to work in this age group [16]. Therefore, if the initial job evaluation and training of people with disabilities take place correctly, it is hoped that people with disabilities will be able to participate in work environments actively.

Although 52.4% of people with sensory and motor disabilities in Namin with university-level education considered “getting hired” as their priority, more than half of those with a school diploma or lower educational level set “self-employment” as their priority. In the study by Ali et al. people with disabilities preferred government offices (75%) to private organizations. They related their findings to better health benefits, more accommodations offered in those jobs, and a lower likelihood of employment discrimination [16]. In the present study, another reason for the tendency of people at higher educational levels to be employed rather than self employment might be related to the nature of their speciality which requires them to work as a team member or buying expensive accommodation to run their own business. Further studies would be needed to identify other reasons for the tendency of people with higher educational levels to be employed, compared with the preference of those with lower educational levels for self-employment. In this study, 15.6% of men and 2.8% of women expressed their interest in entrepreneurship. Supporting this group might help people with disabilities take a more active role and exert greater influence in the Namin job market.

Based on our findings, 67% of people with sensory and motor disabilities preferred to work part-time. While in Poland, 27–38% of people with moderate and severe disabilities tended to work part-time, as their health problems made full-time work difficult or impossible for them [17]. The contradictions between the results of the two studies might be due to cultural differences, the rules and conditions of the work environment, or the degree of environmental modification in those places.

The results of the present study demonstrated that more than 75% of people with disabilities prefer to work at home, which could be due to socio-cultural and physical environmental barriers. A lack of appropriate transportation and environmental modification were mentioned as barriers to work outside the home by 59.4% and 55.5% of individuals, respectively, and 57.9% stated that buildings in rural and urban areas are not appropriate for people with disabilities to stay and work for a few hours. These barriers were also reported in the other parts of Iran, such as Shahin Dezh in West Azerbaijan Province and Tehran City [18, 19].

Conclusion

Almost all people with sensory-motor disabilities at working age were interested in employment, but most preferred working at home or in part-time jobs. Among popular jobs in the area, selling, handicraft design, teaching and training, ranching, and agriculture were the most popular choices. Moreover, job-readiness for becoming a seller and for ranching were the most frequently reported fields. The teaching and training of people with disabilities need special attention so that the literacy rate and skills of individuals with sensory motor disabilities become similar to those of the general population. AT awareness evaluation, AT needs assessment, and AT provision are the other areas that require special attention. The assessment provided the opportunity to collect and categorize information related to the knowledge, skills, physical abilities, and job preferences of people with sensory motor disabilities, which, in turn, helped the researchers detect people with job readiness in different fields of work, rehabilitation, assistive devices, and training needs according to their most preferred jobs.

Implications and limitations of the study

Of course, the information obtained from the self-reporting about job interests, capabilities and skills of people with disabilities should be completed by further specialized evaluations. This study covered the current employment status employment status in Namin, which should be followed by a market survey. This model was successfully used to collect and categorize the information needed for the career planning of individuals with disabilities in the city of Namin. It is highly recommended that future studies examine its usefulness in other communities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.111). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before filling out the questionnaire.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Nikta Hatamizadeh, Sonia Moradazar, Elham Loni, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Formal analysis: Nikta Hatamizadeh and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Investigation: Sonia Moradazar; Methodology: Nikta Hatamizadeh, Elham Loni, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Project administration: Sonia Moradazar; Supervision: Nikta Hatamizadeh; Writing the original draft: Nikta Hatamizadeh and Sonia Moradazar; Review, and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank people with disabilities who participated in this study.

References

It is estimated that about 1.3 billion people with disabilities live around the world [1], 55% of whom are of working age [2].

In developing countries, the rate of unemployment is 80–90% among working-aged people with disabilities [3]. Unfortunately, the gap in the employment of people with and without disabilities has not decreased over the past decade [4]. According to a study by Bonaccio et al. on the participation of people with disabilities throughout the employment cycle, one of the main reasons for the lack of jobs among these people is a pessimistic belief in their ability to perform work-related tasks [5].

Obviously, the job of people with disabilities must be consistent with their physical abilities. Otherwise, they cannot handle their work and would feel rejected [6, 7]. Thus, job matching plays an integral role in the integration of this group into the workforce [8]. In facilitating the employment of job seekers with disabilities, the first step is to obtain information about their knowledge, skills, and interests, and to identify employers’ needs and interests to match them accordingly [9]. Anand and Sevak indicated that people with sensory, motor, or mental disabilities whose work-related tasks matched their capabilities reported more long-term employment than the others [10].

The engagement of people with disabilities in the workforce has received special attention in the government’s macro-planning. Providing vocational rehabilitation and enhancing the job-readiness of people with disabilities are among the missions of welfare organizations in many countries [11], including Iran. Such actions aim to help these people become employed and enjoy independent lives.

According to a study by the Welfare Organization, using cluster sampling, about 11.5% of Iran’s population lives with disabilities, and the prevalence rates of motor, visual, and hearing impairments are 6.6%, 3.6%, and 1.8%, respectively [12]. The city of Namin is located in Ardabil Province in northwest Iran. The prevalence rate of disability in this province is 12.7%, which is slightly higher than the mean rate of the country. Based on the 2016 census, the total population of this city is 13659 [13]. The relative prevalence of motor, visual, and hearing impairments among people with disabilities in Ardabil province is 42%, 19%, and 15%, respectively [12].

In general, 163 people with sensory and/or motor disabilities of working age (16–60 years old) were enrolled in the Welfare Organization of Namin, in 2022 [1]. This organization provided vocational rehabilitation services to people with disabilities who registered their names and sought work. Although data were available on the physical, mental, social, and environmental status of the registered people, there was little information about their job interests, capabilities, and skills. It should be noted that this information is mandatory for running readiness programs for people with sensory and motor disabilities, to facilitate their participation in popular jobs in their region. Accordingly, the present study aims to estimate the current employment status, job preferences, and capabilities of people with sensory-motor disabilities in Namin.

Materials and Methods

This survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Using the census method, all 163 people with sensory and/or motor disabilities aged between 16 and 60 years who were registered in the Welfare Organization of Namin were invited to join the study. The survey questionnaire was developed by the research team and subsequently modified several times in terms of format, question wording, and answer choices. The opinions of university colleagues working in different departments (i.e. rehabilitation management, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, ergonomics, rehabilitation engineering, health professionals working in the vocational rehabilitation office of welfare organizations, and people with disabilities of working age) were collected for this purpose. The resulting questionnaire comprised 39 questions and was divided into four parts.

The first part was composed of 5 questions about the participants’ demographic characteristics. Items in the second one asked about one’s current job, job interests, and skills (questions 6–23). This part began with questions about their work experiences and technical skills, as well as the jobs of others around them (e.g. relatives and acquaintances). These questions were icebreakers and were intended to help the person focus on the subject of the questionnaire. The third part covered questions on eight general fields of the job market and common jobs in Namin (questions 24–34). In each field, the work areas were named, and the participants were asked about their level of interest in each job as well as the levels of their technical skills and physical capabilities for engaging in the work that they were interested in. The fourth part consisted of items related to the minimum salary they expected, types of disabilities they had, and probable use of assistive devices (questions 35–39).

The questionnaire was completed by 12 people with disabilities to mention their opinions about clarity and ease of answering by checkmark (yes/no) for each question, and to write their suggestions in case any question was unclear or difficult to answer. The respondents confirmed clarity and ease of answering the questions. The content validity of the survey questionnaire was examined using the Lawshe method, and the content validity index was 0.97. In addition, the questionnaire’s reliability was assessed using the test-re-test method. Kappa reliability coefficients for the questionnaire’s items ranged from 0.84 to 0.96.

SPSS software, version 23, was used for data analysis. Moreover, the chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to determine the relationship between individual variables and job interests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 163 people with sensory and motor disabilities participated in this study. The male-to-female ratio was 95:68. More than 61% of the participants were married, while the remaining participants were single. Table 1 presents the employment status of people with sensory and motor disabilities by gender, disability type, educational level, and place of residence.

Based on the results, the employment rate among males (40%) was higher than among females (32.4%). In addition, the frequency of employment of people with motor and visual disabilities was higher (36.3% and 43.5%) than that of people with hearing and multiple disabilities (34.5% and 33.3%). The highest employment rate (52.4%) was among people with higher education, whereas people with a diploma had the lowest employment rate (24.1%). Finally, the employment rate was higher among people aged 26–45 than among younger and older people.

It is noteworthy that all participants were interested in work engagement, with only 7(3.5%) not interested in employment. Table 2 provides data on the job preferences of people interested in work, including preferred time and place of work, by gender, type of disability, educational level, and place of residence.

The results revealed that 32.7% of people were interested in full-time work; this interest was more pronounced among men (47.8%) than among women (10.9%) (P<0.001).

Moreover, men (30.4%) were more interested in working outside the home than women (12.5%), and people with higher education (42.9%) were more interested than those with a diploma or lower educational levels (P<0.001).

Each participant was asked to mark one or more fields of employment that they were interested in. Table 3 lists the fields of interest of the 156 people with disabilities who have stated their willingness to be employed.

Nearly 73.6% of people with sensory and motor disabilities expressed their interest in trading jobs, and more than 50% were interested in working in each of the fields of “design, writing, and art”, “agriculture, aviculture, fish farming, and ranching”, and “working in factories”. The areas of job interest and related job readiness are presented in Table 4.

Selling, handicraft design, and teaching and training jobs, as well as ranching and agriculture, were the jobs of choice for more people than other jobs, and readiness for being a seller or doing ranching were the most frequently reported fields of work (Table 4).

Discussion

This section is arranged into two parts: “Current employment status and career interests” and “capabilities of people with sensory and motor disabilities”.

Current employment status

The illiteracy rate in the general population at working age was 12.9% among males and 26.3% among females, based on the 2016 Census [13]. According to the present study, these rates were 14.7% and 35.3% among males and females with sensory and motor disabilities, respectively. According to the census, the unemployment rate was 14%, which was 4 times lower than that of people with sensory and motor disabilities, which was found to be 63% in this study. These figures highlight the need for action to reduce gaps between people with disabilities, especially females with disabilities, and others, according to educational levels, skills training, and employment.

Our findings revealed that the employment rate among people with higher educational levels (53%) was higher than that among those with high school levels (34%). Anand Sevak reported the same result in the three states of Mississippi, New Jersey, and Ohio in the USA [10].

In the present study, among people with disabilities, the employment rate was higher in the middle-aged group (26–45 years old) than in the younger and older groups. This reverse U-shape curve is similar to that of the employment rate in the general population [14].

In this study, only 42% of people with sensory and motor disabilities used any assistive technology (AT). Considering that using AT would help people with disabilities become independent in different aspects of life and improve job readiness, assessing people’s awareness of ATs that would be useful to them and conducting AT needs assessments would provide valuable information for planning AT provision for people with disabilities.

Job preferences of people with sensory-motor disabilities

Some employers believe that people with disabilities do not want to work at all, which might negatively affect their decision to hire people with disabilities [15]. Based on the findings of the present study, 96% of working-age people with sensory and motor disabilities desired to work in Namin. This result indicates that the above-mentioned belief of employers is not right, which is in line with the results of a survey in the United States (2011), showing that 80% of people with disabilities were eager to work in this age group [16]. Therefore, if the initial job evaluation and training of people with disabilities take place correctly, it is hoped that people with disabilities will be able to participate in work environments actively.

Although 52.4% of people with sensory and motor disabilities in Namin with university-level education considered “getting hired” as their priority, more than half of those with a school diploma or lower educational level set “self-employment” as their priority. In the study by Ali et al. people with disabilities preferred government offices (75%) to private organizations. They related their findings to better health benefits, more accommodations offered in those jobs, and a lower likelihood of employment discrimination [16]. In the present study, another reason for the tendency of people at higher educational levels to be employed rather than self employment might be related to the nature of their speciality which requires them to work as a team member or buying expensive accommodation to run their own business. Further studies would be needed to identify other reasons for the tendency of people with higher educational levels to be employed, compared with the preference of those with lower educational levels for self-employment. In this study, 15.6% of men and 2.8% of women expressed their interest in entrepreneurship. Supporting this group might help people with disabilities take a more active role and exert greater influence in the Namin job market.

Based on our findings, 67% of people with sensory and motor disabilities preferred to work part-time. While in Poland, 27–38% of people with moderate and severe disabilities tended to work part-time, as their health problems made full-time work difficult or impossible for them [17]. The contradictions between the results of the two studies might be due to cultural differences, the rules and conditions of the work environment, or the degree of environmental modification in those places.

The results of the present study demonstrated that more than 75% of people with disabilities prefer to work at home, which could be due to socio-cultural and physical environmental barriers. A lack of appropriate transportation and environmental modification were mentioned as barriers to work outside the home by 59.4% and 55.5% of individuals, respectively, and 57.9% stated that buildings in rural and urban areas are not appropriate for people with disabilities to stay and work for a few hours. These barriers were also reported in the other parts of Iran, such as Shahin Dezh in West Azerbaijan Province and Tehran City [18, 19].

Conclusion

Almost all people with sensory-motor disabilities at working age were interested in employment, but most preferred working at home or in part-time jobs. Among popular jobs in the area, selling, handicraft design, teaching and training, ranching, and agriculture were the most popular choices. Moreover, job-readiness for becoming a seller and for ranching were the most frequently reported fields. The teaching and training of people with disabilities need special attention so that the literacy rate and skills of individuals with sensory motor disabilities become similar to those of the general population. AT awareness evaluation, AT needs assessment, and AT provision are the other areas that require special attention. The assessment provided the opportunity to collect and categorize information related to the knowledge, skills, physical abilities, and job preferences of people with sensory motor disabilities, which, in turn, helped the researchers detect people with job readiness in different fields of work, rehabilitation, assistive devices, and training needs according to their most preferred jobs.

Implications and limitations of the study

Of course, the information obtained from the self-reporting about job interests, capabilities and skills of people with disabilities should be completed by further specialized evaluations. This study covered the current employment status employment status in Namin, which should be followed by a market survey. This model was successfully used to collect and categorize the information needed for the career planning of individuals with disabilities in the city of Namin. It is highly recommended that future studies examine its usefulness in other communities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.111). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before filling out the questionnaire.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Nikta Hatamizadeh, Sonia Moradazar, Elham Loni, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Formal analysis: Nikta Hatamizadeh and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Investigation: Sonia Moradazar; Methodology: Nikta Hatamizadeh, Elham Loni, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Project administration: Sonia Moradazar; Supervision: Nikta Hatamizadeh; Writing the original draft: Nikta Hatamizadeh and Sonia Moradazar; Review, and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank people with disabilities who participated in this study.

References

- WHO. Disability. Geneva: WHO; 2025. [Link]

- World bank. Age dependency ratio (% of working-age population) [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 2025 December 17]. Available from: [Link]

- United Nations. Factsheet on persons with disabilities [Internet]. 2007 [Updated 2025 December 17]. Available from: [Link]

- OECD. Disability, work and inclusion mainstreaming in all policies and practices. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2022. [Link]

- Bonaccio S, Connelly CE, Gellatly IR, Jetha A, Martin Ginis KA. The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: Employer concerns and research evidence. J Bus Psychol. 2020; 35(2):135-58. [DOI:10.1007/s10869-018-9602-5] [PMID]

- Tabatabaei S. Study of self-esteem and mental health of physically handicapped in relation to their employment status in Iran [doctoral dissertation]. Chandigarh: Panjab University; 2003.

- Kozak A, Kersten M, Schillmöller Z, Nienhaus A. Psychosocial work-related predictors and consequences of personal burnout among staff working with people with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2013; 34(1):102-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.021] [PMID]

- Suresh V, Dyaram L. Job matching for persons with disabilities: an exploratory study. Empl Responsib Rights J. 2023; 35:475-92. [DOI:10.1007/s10672-022-09421-6]

- Inge K, Targett P. Identifying job opportunities for individuals with disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2006; 25(2):137-9. [DOI:10.3233/JVR-2006-00350]

- Anand P, Sevak P. The role of workplace accommodations in the employment of people with disabilities. IZA J Labor Policy. 2017; 6:12. [DOI:10.1186/s40173-017-0090-4]

- Approvals of the Islamic Council. [Law on protection of the rights of the disabled (chapter five) (Persian)]. Tehran: Approvals of the Islamic Council; 2017.

- Abbasi F, Saffari Fard A, Jahanshad SH, Davatgaran K, Veysani Y. [Atlas of prevalence and cause of impairments and disabilities in Iran (Persian)]. Tehran: Welfare Organization Publication; 2024.

- Plan and Budget Organization. [Iran statistical year book (Persian)] [Internet]. Tehran: Iran Statistics Center; 2016. [Link]

- Zhao H, O’Connor G, Wu J, Lumpkin GT. Age and entrepreneurial career success: A review and a meta-analysis. J Bus Ventur. 2021; 36(1):106007. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106007]

- Hemphill E, Kulik CT. Which employers offer hope for mainstream job opportunities for disabled people? Soc Policy Soc. 2016; 15(4):537-54. [DOI:10.1017/S1474746415000457]

- Ali M, Schur L, Blanck P. What types of jobs do people with disabilities want? J Occup Rehabil. 2011; 21(2):199-210. [DOI:10.1007/s10926-010-9266-0] [PMID]

- Michna A, Kmieciak R, Burzyńska‐Ptaszek K. Job preferences and expectations of disabled people and small and medium‐sized enterprises in Poland: implications for disabled people’s professional development. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2017; 28(3):299-336. [DOI:10.1002/hrdq.21280]

- Azhdari A, Meghami A. [Examining the issues of employment and unemployment of people with disability an emphasis on the effectiveness of career counseling (a case study of Shahin Dezh city) (Persian)]. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018; 4(14):85-97. [Link]

- Shabannia Mansour M, Mahmoudi SH. [Examining the effectiveness of protective laws and regulations on the willingness of disabled women in Tehran to work (Persian)]. Womens Strateg Stud. 2019; 21(82):35-55. [DOI:10.22095/jwss.2019.92500]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Rehabilitation management

Received: 2025/07/9 | Accepted: 2025/10/22 | Published: 2025/11/28

Received: 2025/07/9 | Accepted: 2025/10/22 | Published: 2025/11/28