Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Riyahi A, Abdolrazaghi H, Nobakht Z. The Relationship Between the Functional Status of Children With Cerebral Palsy and Physiological and Topographical Classification. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-308-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-308-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran.

2- Department of Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Sina Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,nobakht.zahra@gmail.com

2- Department of Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Sina Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Cerebral palsy (CP) classification system, Physiological classification, Topographical distribution

Full-Text [PDF 643 kb]

(54 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (235 Views)

Full-Text: (26 Views)

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of permanent disorders that causes activity limitations and is attributed to non-progressive disturbances [1, 2]. CP occurs in about 2–2.5 per 1000 live births [3]. The average prevalence of CP in Iran is reported as 2 per 1000 live births [4]. The associated problems with CP include disturbances in cognition, sensations, perception, communication, behavior, seizures, secondary musculoskeletal disorders, and incontinence [5].

The classification of children with CP in the last two decades has been based on criteria such as central control and area involved in the brain, the nature and type of motor disorder, physiological distributions, and functional motor abilities. The physiological classification divides CP into spastic paralysis, dyskinesia, ataxia, hypotonic, and mixed. Spastic CP is the most common type and usually covers half of these children. Spastic muscles are stiff and strongly resist the stretch. These muscles are excessively activated, resulting in dry and harsh movements. Muscle spasticity generally changes over time. Dyskinetic paralysis involves disturbances in the control and coordination of movements, affecting approximately a quarter of these children. Torsional, involuntary, and repetitive movements are the characteristics of these children. Their uncontrollable movements generally increase during stressful times and disappear during sleep. Ataxia paralysis is the rarest type (about 10%). Disturbance in the sense of balance and perception of depth is one of its symptoms. The muscle tone of these children is low, and their muscles are flaccid. Their walk is staggering, and their upper extremities are unstable when walking. Muscle tone is abnormally reduced. It is the most commonly impaired muscle tone in early neonates with neurological abnormalities. In mixed paralysis, conditions previously described in the four types of CP occur in combination. About a quarter of children with CP are classified in this type [4]. Spastic CP is divided into 5 categories based on the topographic distribution: Quadriplegia (involvement of all four limbs), diplegia (usually the lower limb is more involved than the upper limb), hemiplegia (involvement of one side of the body; normally the upper limb is more involved than the lower limb), triplegia (involvement of three limbs, typically two hands and one leg), and monoplegia (only one limb is involved, usually one hand) [6, 7]. These classifications do not provide a clear picture of the child’s performance and ability consistent with the International Classification of Functioning; all are based on disability. Therefore, the functional performance of upper and lower limbs should be classified by functional scales [8, 9].

A group of classification systems focusing on manual function includes the House classification, modified House classification, and Zancolli classification systems. The other group focuses on manual functional capacity (e.g. what a child can do). However, none of these classifications describes everyday routines. Therefore, there was a need for a simple and fluid instrument that focuses on the implementation of daily activities [6]. In recent years, functional categories have been used to describe the heterogeneous group of children with CP and to recognize the diagnosis of CP. Since 1997, two systems have been developed for classifying children with CP based on their functional ability: The GMFCS-E&R system and the manual abilities classification system (MACS) [8].

CP neurological symptoms can be detected through early imaging and clinical tests. Determining the type of CP can be challenging during the first year of life. Diagnosis should be confirmed when the child is about 4 years of age. However, it is important to describe the child’s functional ability as soon as possible. The most important thing for the parents of children with CP is the symptoms of CP. The use of a functional classification system demonstrates a shift whereby researchers and physicians consider the results of CP in terms of its impact on the child’s daily performance, rather than in terms of neurological states and milestones. After determining the range of performance limits for resource allocation, it is necessary to facilitate studies on the causes, prevention, or prognosis of these limitations [10]. Gross motor function and manual ability limitation are disturbed differently in the physiologic and topographic CP classifications. This study aims to determine the functional status of CP children and their relationship with the physiological and topographical classification of CP.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional non-interventional study was used to determine the functional status of children with CP and its relationship with the CP physiologic and topographic classification. The child’s functional level was assessed by an examiner who was familiar with the scales and had received prior training in their use. Samples of the study consisted of children with CP aged between 4 and 18 years who were referred to all clinics, rehabilitation centers, and exceptional schools in Tehran and Arak.

The inclusion criteria for participants included children with CP aged 4–18 years old. On the other hand, participants were excluded from the study if they were unwilling to continue cooperating. All data were analyzed by IBM SPSS software, version 20.

Study instruments

Gross motor function classification system

The gross motor function classification system (GMFCS) is a standardized classification system that divides children with CP into five levels based on their current gross motor abilities. Level I shows the maximum independence, while Level V displays the least independence in performance. This scale was translated into Persian by Dehghan et al. [11].

Manual ability classification system

The manual ability classification system (MACS) is one of the most important tools, where the use of hands is classified as manipulating objects during everyday activities of children with CP. This scale offers a new perspective on the functional classification of manual ability in children and adults with CP, focusing on the severity of upper limb impairment. The child will be placed in one of the five MACS levels. These groupings are based on a child’s ability to manipulate objects. Level I demonstrates the best manual ability, whereas level V shows a lack of active manual function. This scale is widely used and has been translated into Persian, with updates by Riyahi et al. [12].

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test of association was utilized to discover the relationship between categorical variables.

Results

The distribution of demographic information of participants is presented in Table 1.

A total of 305 children with CP participated in this study, including 174 males (57%) and 131 females (43%).

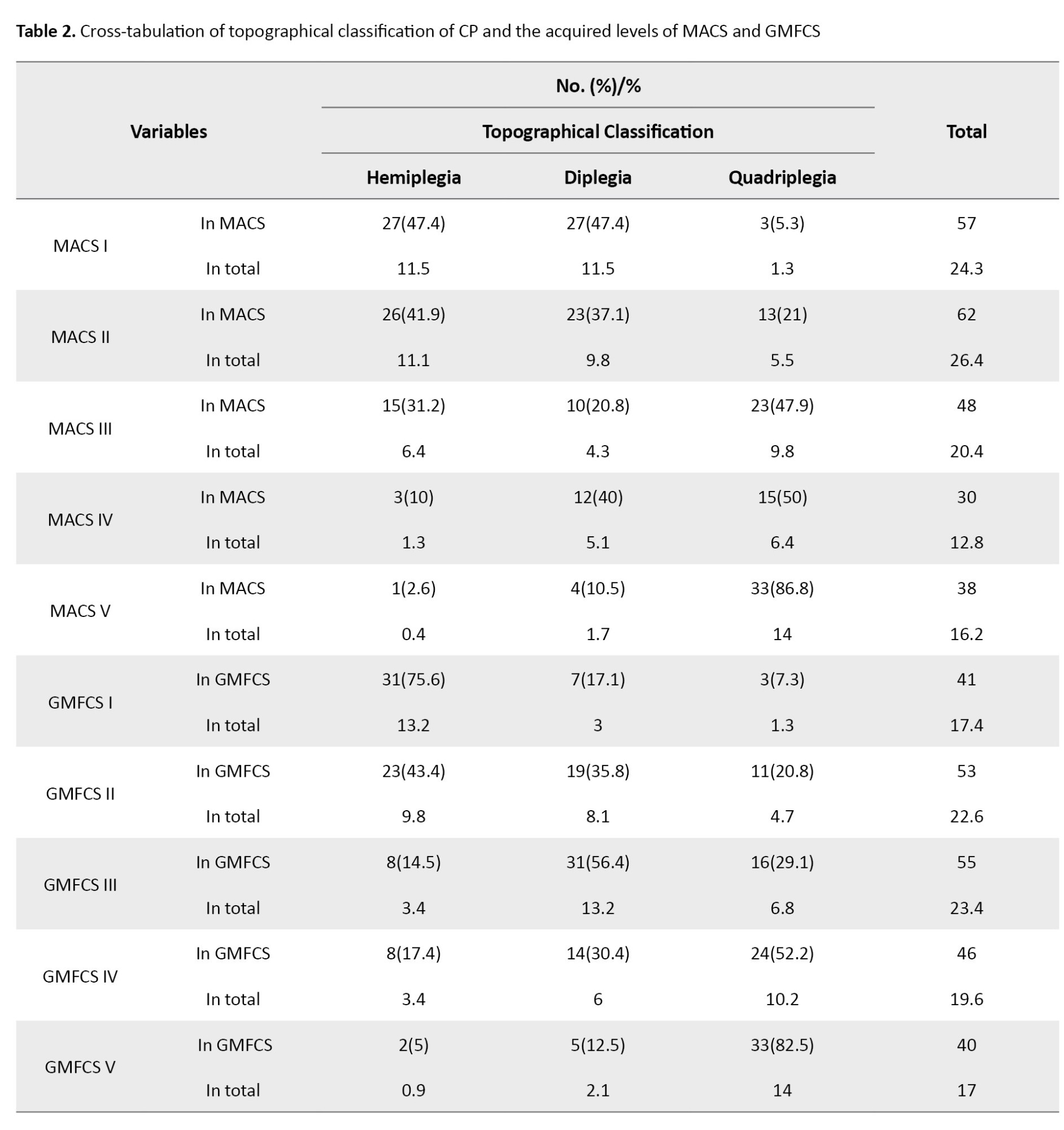

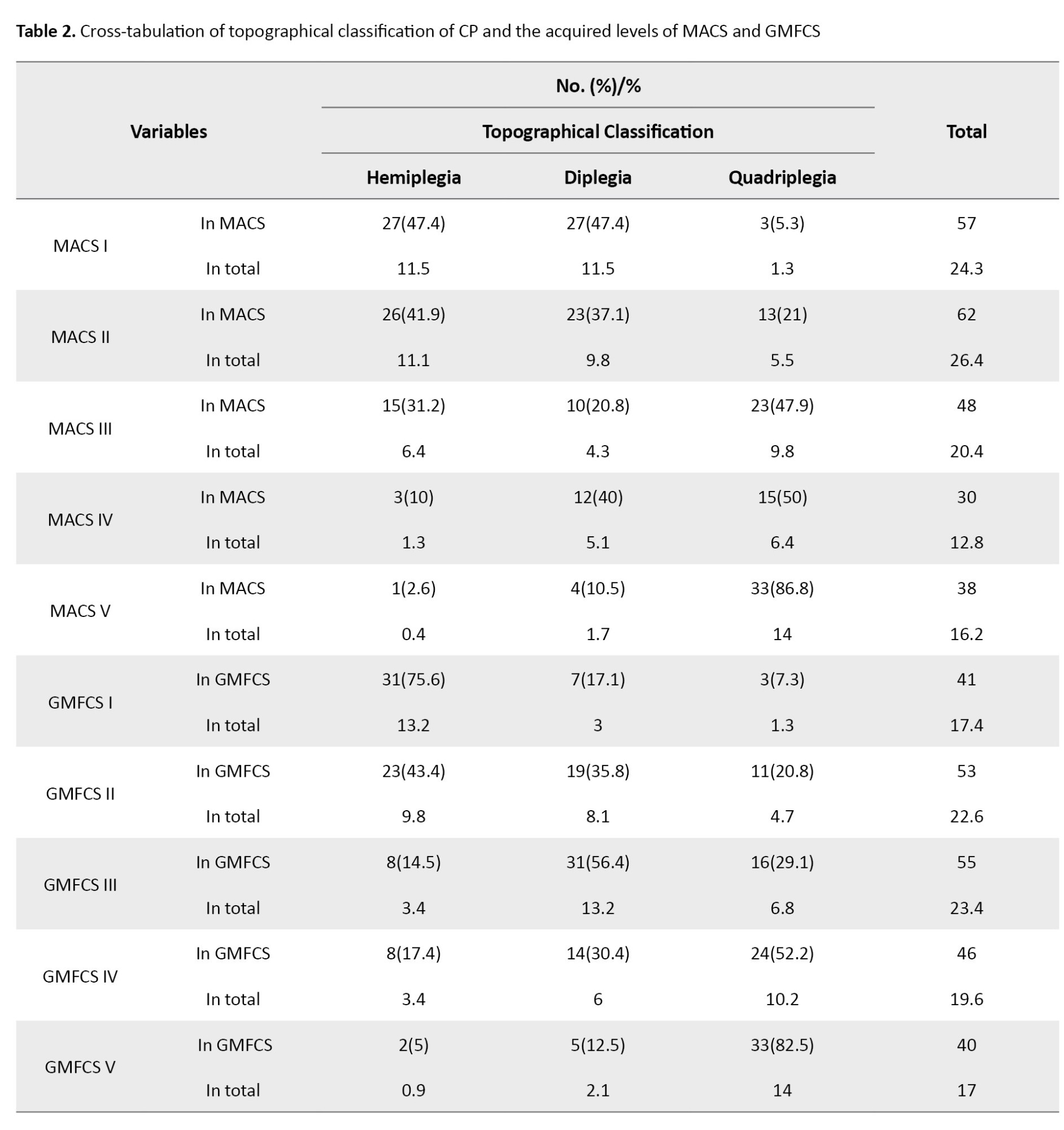

The Pearson chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between topographical classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS and GMFCS in children with spastic CP (Table 2).

There was a statistically significant association between the topographical classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS (χ=82.436, P<0.01) and GMFCS (χ=103.331, P<0.01) in children with spastic CP.

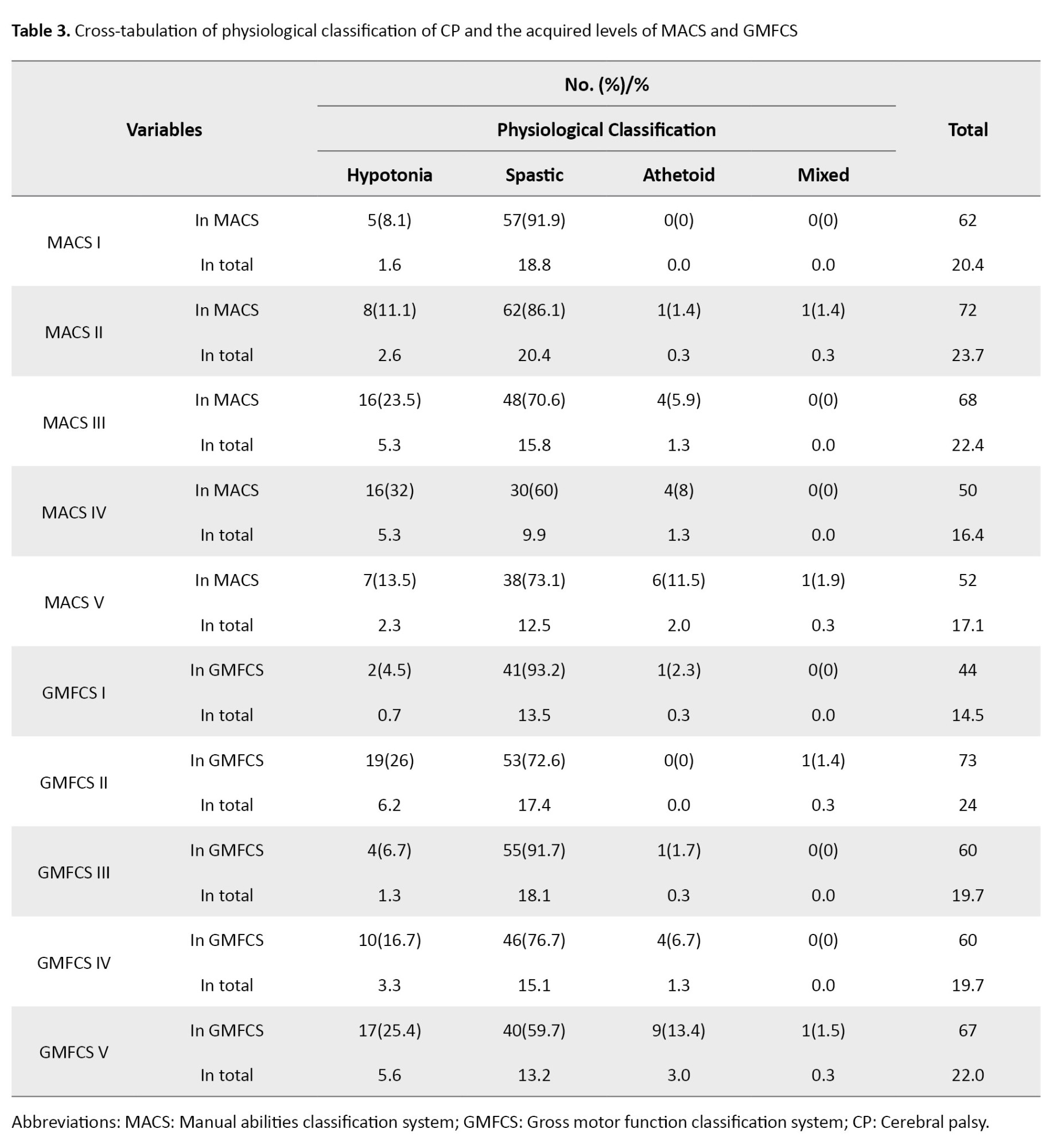

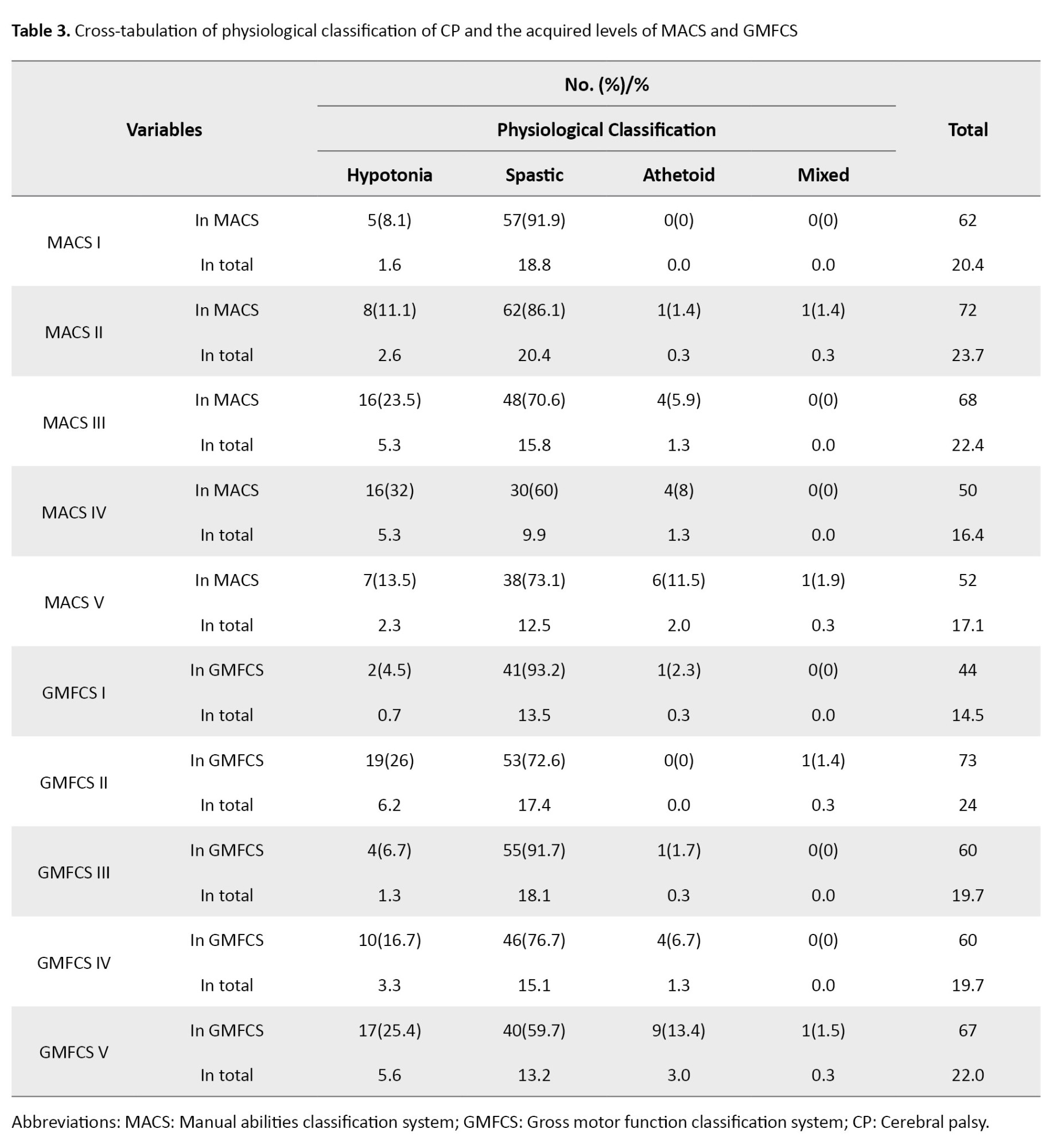

The Pearson chi-square test was employed to find the relationship between the physiological classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS and GMFCS in children with CP (Table 3).

Based on the results, a statistically significant association was observed between the physiological classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS (χ=31.498, P<0.01) and GMFCS (χ=37.950, P<0.01) in children with CP.

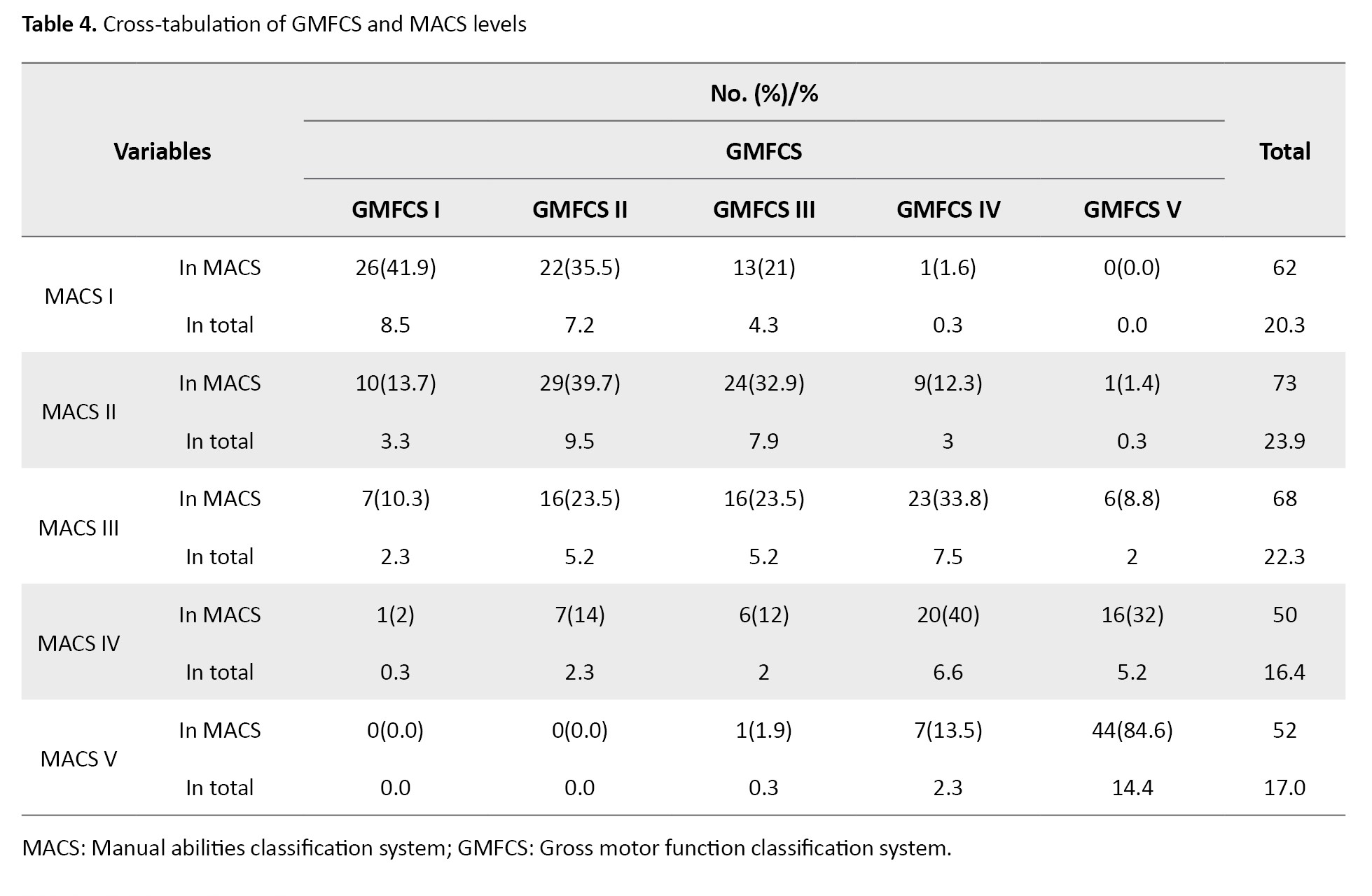

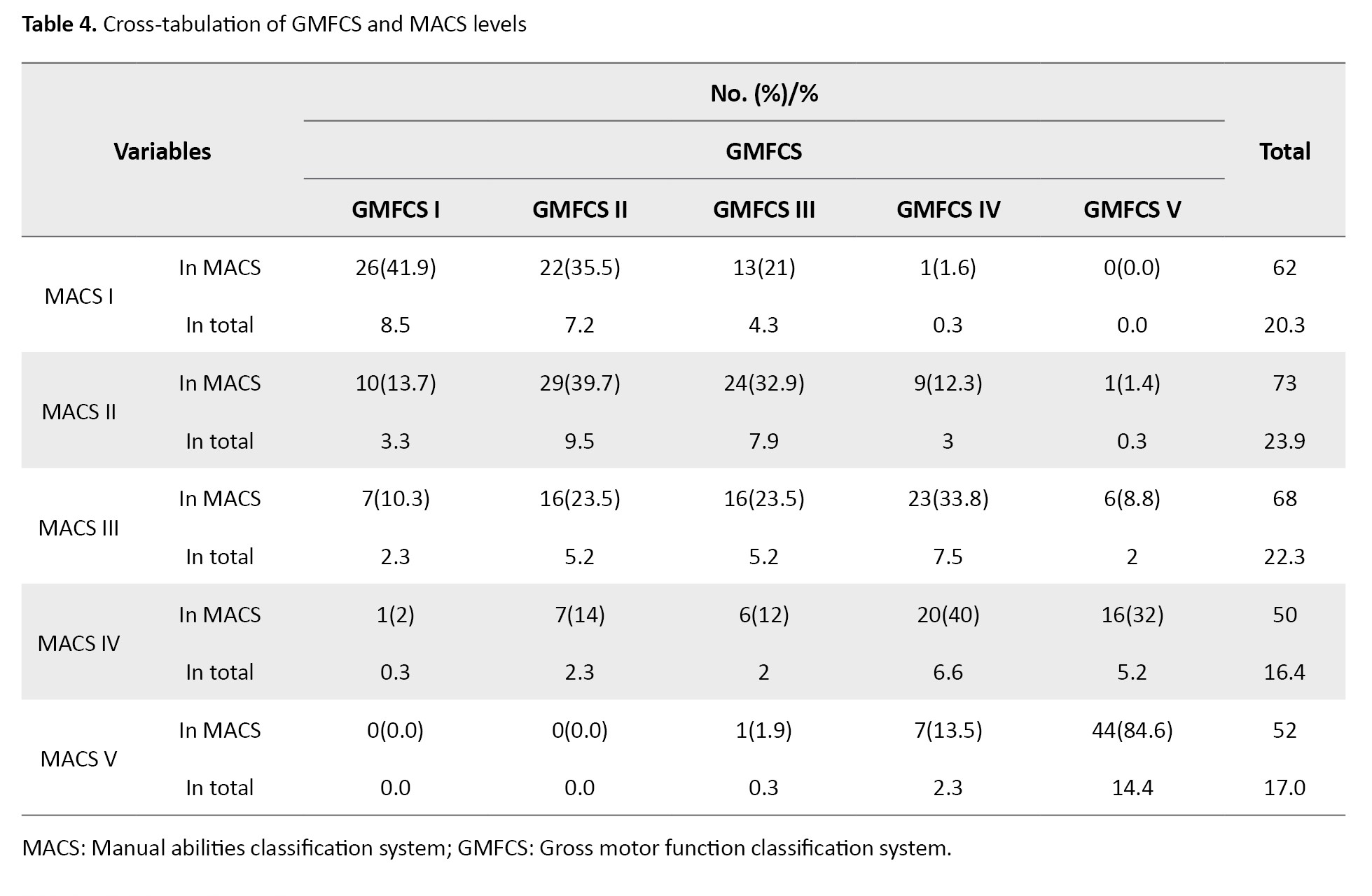

The Pearson chi-square test was utilized to identify the relationship between the acquired level of GMFCS and the acquired level of MACS in children with CP (Table 4).

The results revealed a statistically significant association between GMFCS and MACS levels in children with CP (χ²=247.271, P<0.01).

Discussion

This study evaluated the relationship between the functional status of children with CP and the topographical and physiological classifications of CP. Initially, the relationship between the topographical classification of CP and the acquired levels of MACS and GMFSC was investigated. Our results revealed a statistically significant correlation between the levels of the GMFCS and MACS in children with CP, which is in line with the results of other studies. For instance, Gorter et al. investigated the relationship between GMFCS, the distribution of limb involvement, and the type of motor disorder in 657 children with CP aged 1–13 years. They found that in children with diplegia (39% of the total), gross motor function is more limited than manual ability. Their findings showed a good distribution of MACS and GMFCS levels, suggesting that the spastic diplegia subgroup provides sufficient information regarding children’s manual abilities and gross motor function [13].

The overall performance level decreases in both upper and lower extremities with an increase in the number of affected limbs. In hypotonic children, due to overall weakness, and in ataxic children, due to excessive movements and tremors, these characteristics appear to have had a more significant impact on hand function, resulting in lower MACS levels. In contrast, the accompanying characteristics in spastic, athetoid, and mixed children have had less effect on hand function, leading to higher MACS levels. Shi et al. evaluated the relationship between hand function limitation and the type of CP in 280 children with CP. A total of 195 children had cerebral palsy, most of whom were children with diplegia (56.41%). About 65% of spastic children acquired levels I and II of the MACS, while 84.44% of children with mixed CP and 80.95% of children with dyskinesia acquired levels III and IV. Children with spastic CP mostly had mild hand function limitations, while children with mixed and dyskinetic CP had moderate and severe hand function limitations [14]. In children with hypotonia, due to general weakness, and in children with ataxia, due to excessive movement and tremors, these features appear to have a greater impact on hand function, resulting in lower MACS scores. In children with ataxia, due to general weakness and tremors, these features appear to have had a more significant impact on hand function.

Golubović and Slavković studied the level of manual skills (capacity) and its relationship with manual abilities (performance). This cross-sectional study was performed on 30 children with CP aged 8–15 years. Their results confirmed a significant correlation between the acquired levels of MACS and GMFCS [15]. Likewise, Gajewska et al. evaluated the relationship between gross motor function, manual abilities, epilepsy, and mental capacity of children with cerebral palsy. This study was performed on 83 children with CP. They found a significant relationship between MACS and GMFCS [16]. Hidecker et al. studied 222 children with CP aged 2–17 years to examine the correlation between MACS, GMFCS, and the communication function classification system and observed a high correlation (R=0.49) between MACS and GMFCS levels [17]. Mutlu et al. investigated 448 children with CP aged 4–15 years to explore the relationship between MACS and GMFCS, reporting an overall agreement of 41%. The agreement was 42%, 40%, 60%, and 28% for spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, and mixed children, respectively (K=0.235, P<0.001) [18].

In the present study, a greater number of participants were distributed at the same levels of MACS and GMFCS, indicating that gross motor function may influence manual ability and the acquired level of MACS. Therefore, it was observed that more participants were found at the same level within the MACS and GMFCS, highlighting a significant relationship between the two.

This study revealed that the results of these systems align with the results of previous traditional classifications (e.g. topographic and physiological). The old systems place more emphasis on impairment and disability, while the new systems focus on individual abilities and performance in daily life.

Conclusion

These findings underscore the importance of understanding the relationship between the physiological classification of CP and its associated functional abilities. The significant correlations identified in our study indicated that targeted interventions can be designed to improve motor function and the overall quality of life for children with CP, particularly by addressing the specific needs associated with their classification levels.

One limitation of our study was the inadequate distribution in certain subgroups. It is recommended that further studies focus on exploring the performance, activity levels, and participation of school-aged children with CP and their relationship with the acquired levels of MACS and GMFCS.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran (Code: IR.ARAKMU.REC.1395.188). Informed written consent was obtained from all parents.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Azade Riyahi, Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi, and Zahra Nobakht; Funding acquisition: Azade Riyahi; Resources: Azade Riyahi; Investigation: Azade Riyahi; Methodology: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Data curation: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Formal analysis: Zahra Nobakht; Software: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Supervision: Azade Riyahi; Validation: Azade Riyahi; Visualization: Azade Riyahi; Writing the original draft: Zahra Nobakht; Review and editing: Zahra Nobakht.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank children and their families for their cooperation.

References

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of permanent disorders that causes activity limitations and is attributed to non-progressive disturbances [1, 2]. CP occurs in about 2–2.5 per 1000 live births [3]. The average prevalence of CP in Iran is reported as 2 per 1000 live births [4]. The associated problems with CP include disturbances in cognition, sensations, perception, communication, behavior, seizures, secondary musculoskeletal disorders, and incontinence [5].

The classification of children with CP in the last two decades has been based on criteria such as central control and area involved in the brain, the nature and type of motor disorder, physiological distributions, and functional motor abilities. The physiological classification divides CP into spastic paralysis, dyskinesia, ataxia, hypotonic, and mixed. Spastic CP is the most common type and usually covers half of these children. Spastic muscles are stiff and strongly resist the stretch. These muscles are excessively activated, resulting in dry and harsh movements. Muscle spasticity generally changes over time. Dyskinetic paralysis involves disturbances in the control and coordination of movements, affecting approximately a quarter of these children. Torsional, involuntary, and repetitive movements are the characteristics of these children. Their uncontrollable movements generally increase during stressful times and disappear during sleep. Ataxia paralysis is the rarest type (about 10%). Disturbance in the sense of balance and perception of depth is one of its symptoms. The muscle tone of these children is low, and their muscles are flaccid. Their walk is staggering, and their upper extremities are unstable when walking. Muscle tone is abnormally reduced. It is the most commonly impaired muscle tone in early neonates with neurological abnormalities. In mixed paralysis, conditions previously described in the four types of CP occur in combination. About a quarter of children with CP are classified in this type [4]. Spastic CP is divided into 5 categories based on the topographic distribution: Quadriplegia (involvement of all four limbs), diplegia (usually the lower limb is more involved than the upper limb), hemiplegia (involvement of one side of the body; normally the upper limb is more involved than the lower limb), triplegia (involvement of three limbs, typically two hands and one leg), and monoplegia (only one limb is involved, usually one hand) [6, 7]. These classifications do not provide a clear picture of the child’s performance and ability consistent with the International Classification of Functioning; all are based on disability. Therefore, the functional performance of upper and lower limbs should be classified by functional scales [8, 9].

A group of classification systems focusing on manual function includes the House classification, modified House classification, and Zancolli classification systems. The other group focuses on manual functional capacity (e.g. what a child can do). However, none of these classifications describes everyday routines. Therefore, there was a need for a simple and fluid instrument that focuses on the implementation of daily activities [6]. In recent years, functional categories have been used to describe the heterogeneous group of children with CP and to recognize the diagnosis of CP. Since 1997, two systems have been developed for classifying children with CP based on their functional ability: The GMFCS-E&R system and the manual abilities classification system (MACS) [8].

CP neurological symptoms can be detected through early imaging and clinical tests. Determining the type of CP can be challenging during the first year of life. Diagnosis should be confirmed when the child is about 4 years of age. However, it is important to describe the child’s functional ability as soon as possible. The most important thing for the parents of children with CP is the symptoms of CP. The use of a functional classification system demonstrates a shift whereby researchers and physicians consider the results of CP in terms of its impact on the child’s daily performance, rather than in terms of neurological states and milestones. After determining the range of performance limits for resource allocation, it is necessary to facilitate studies on the causes, prevention, or prognosis of these limitations [10]. Gross motor function and manual ability limitation are disturbed differently in the physiologic and topographic CP classifications. This study aims to determine the functional status of CP children and their relationship with the physiological and topographical classification of CP.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional non-interventional study was used to determine the functional status of children with CP and its relationship with the CP physiologic and topographic classification. The child’s functional level was assessed by an examiner who was familiar with the scales and had received prior training in their use. Samples of the study consisted of children with CP aged between 4 and 18 years who were referred to all clinics, rehabilitation centers, and exceptional schools in Tehran and Arak.

The inclusion criteria for participants included children with CP aged 4–18 years old. On the other hand, participants were excluded from the study if they were unwilling to continue cooperating. All data were analyzed by IBM SPSS software, version 20.

Study instruments

Gross motor function classification system

The gross motor function classification system (GMFCS) is a standardized classification system that divides children with CP into five levels based on their current gross motor abilities. Level I shows the maximum independence, while Level V displays the least independence in performance. This scale was translated into Persian by Dehghan et al. [11].

Manual ability classification system

The manual ability classification system (MACS) is one of the most important tools, where the use of hands is classified as manipulating objects during everyday activities of children with CP. This scale offers a new perspective on the functional classification of manual ability in children and adults with CP, focusing on the severity of upper limb impairment. The child will be placed in one of the five MACS levels. These groupings are based on a child’s ability to manipulate objects. Level I demonstrates the best manual ability, whereas level V shows a lack of active manual function. This scale is widely used and has been translated into Persian, with updates by Riyahi et al. [12].

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test of association was utilized to discover the relationship between categorical variables.

Results

The distribution of demographic information of participants is presented in Table 1.

A total of 305 children with CP participated in this study, including 174 males (57%) and 131 females (43%).

The Pearson chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between topographical classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS and GMFCS in children with spastic CP (Table 2).

There was a statistically significant association between the topographical classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS (χ=82.436, P<0.01) and GMFCS (χ=103.331, P<0.01) in children with spastic CP.

The Pearson chi-square test was employed to find the relationship between the physiological classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS and GMFCS in children with CP (Table 3).

Based on the results, a statistically significant association was observed between the physiological classification of CP and the acquired level of MACS (χ=31.498, P<0.01) and GMFCS (χ=37.950, P<0.01) in children with CP.

The Pearson chi-square test was utilized to identify the relationship between the acquired level of GMFCS and the acquired level of MACS in children with CP (Table 4).

The results revealed a statistically significant association between GMFCS and MACS levels in children with CP (χ²=247.271, P<0.01).

Discussion

This study evaluated the relationship between the functional status of children with CP and the topographical and physiological classifications of CP. Initially, the relationship between the topographical classification of CP and the acquired levels of MACS and GMFSC was investigated. Our results revealed a statistically significant correlation between the levels of the GMFCS and MACS in children with CP, which is in line with the results of other studies. For instance, Gorter et al. investigated the relationship between GMFCS, the distribution of limb involvement, and the type of motor disorder in 657 children with CP aged 1–13 years. They found that in children with diplegia (39% of the total), gross motor function is more limited than manual ability. Their findings showed a good distribution of MACS and GMFCS levels, suggesting that the spastic diplegia subgroup provides sufficient information regarding children’s manual abilities and gross motor function [13].

The overall performance level decreases in both upper and lower extremities with an increase in the number of affected limbs. In hypotonic children, due to overall weakness, and in ataxic children, due to excessive movements and tremors, these characteristics appear to have had a more significant impact on hand function, resulting in lower MACS levels. In contrast, the accompanying characteristics in spastic, athetoid, and mixed children have had less effect on hand function, leading to higher MACS levels. Shi et al. evaluated the relationship between hand function limitation and the type of CP in 280 children with CP. A total of 195 children had cerebral palsy, most of whom were children with diplegia (56.41%). About 65% of spastic children acquired levels I and II of the MACS, while 84.44% of children with mixed CP and 80.95% of children with dyskinesia acquired levels III and IV. Children with spastic CP mostly had mild hand function limitations, while children with mixed and dyskinetic CP had moderate and severe hand function limitations [14]. In children with hypotonia, due to general weakness, and in children with ataxia, due to excessive movement and tremors, these features appear to have a greater impact on hand function, resulting in lower MACS scores. In children with ataxia, due to general weakness and tremors, these features appear to have had a more significant impact on hand function.

Golubović and Slavković studied the level of manual skills (capacity) and its relationship with manual abilities (performance). This cross-sectional study was performed on 30 children with CP aged 8–15 years. Their results confirmed a significant correlation between the acquired levels of MACS and GMFCS [15]. Likewise, Gajewska et al. evaluated the relationship between gross motor function, manual abilities, epilepsy, and mental capacity of children with cerebral palsy. This study was performed on 83 children with CP. They found a significant relationship between MACS and GMFCS [16]. Hidecker et al. studied 222 children with CP aged 2–17 years to examine the correlation between MACS, GMFCS, and the communication function classification system and observed a high correlation (R=0.49) between MACS and GMFCS levels [17]. Mutlu et al. investigated 448 children with CP aged 4–15 years to explore the relationship between MACS and GMFCS, reporting an overall agreement of 41%. The agreement was 42%, 40%, 60%, and 28% for spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, and mixed children, respectively (K=0.235, P<0.001) [18].

In the present study, a greater number of participants were distributed at the same levels of MACS and GMFCS, indicating that gross motor function may influence manual ability and the acquired level of MACS. Therefore, it was observed that more participants were found at the same level within the MACS and GMFCS, highlighting a significant relationship between the two.

This study revealed that the results of these systems align with the results of previous traditional classifications (e.g. topographic and physiological). The old systems place more emphasis on impairment and disability, while the new systems focus on individual abilities and performance in daily life.

Conclusion

These findings underscore the importance of understanding the relationship between the physiological classification of CP and its associated functional abilities. The significant correlations identified in our study indicated that targeted interventions can be designed to improve motor function and the overall quality of life for children with CP, particularly by addressing the specific needs associated with their classification levels.

One limitation of our study was the inadequate distribution in certain subgroups. It is recommended that further studies focus on exploring the performance, activity levels, and participation of school-aged children with CP and their relationship with the acquired levels of MACS and GMFCS.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran (Code: IR.ARAKMU.REC.1395.188). Informed written consent was obtained from all parents.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Azade Riyahi, Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi, and Zahra Nobakht; Funding acquisition: Azade Riyahi; Resources: Azade Riyahi; Investigation: Azade Riyahi; Methodology: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Data curation: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Formal analysis: Zahra Nobakht; Software: Hosseinali Abdolrazaghi; Supervision: Azade Riyahi; Validation: Azade Riyahi; Visualization: Azade Riyahi; Writing the original draft: Zahra Nobakht; Review and editing: Zahra Nobakht.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank children and their families for their cooperation.

References

- Sankar C, Mundkur N. Cerebral palsy-definition, classification, etiology and early diagnosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2005; 72(10):865-8.[DOI:10.1007/BF02731117] [PMID]

- Odding E, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2006; 28(4):183-91. [DOI:10.1080/09638280500158422] [PMID]

- Rogers B. Feeding method and health outcomes of children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr. 2004; 145(2 Suppl):S28-32. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.019] [PMID]

- Rassafiani M. [Occupational therapists’ decisions about the management of upper limb hyertonicity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy [PhD dissertation]. Brisbane: The University of Queensland; 2006. [DOI:10.14264/158056]

- Rassafiani M, Akbarfahimi N, Sahaf R. Upper limb hypertonicity in children with cerebral palsy: A review study on medical and rehabilitative management. Iran Rehabil J. 2013;11(18):61-71. [Link]

- Gray L, Ng H, Bartlett D. The gross motor function classification system: An update on impact and clinical utility. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2010; 22(3):315-20. [DOI:10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181ea8e52] [PMID]

- Rassafiani M, Sahaf R. Hypertonicity in children with cerebral palsy: A new perspective. Iran Rehabil J. 2011; 11(14):66-74. [Link]

- Kimmerle M, Mainwaring L, Borenstein M. The functional repertoire of the hand and its application to assessment. Am J Occup Ther. 2003; 57(5):489-98. [DOI:10.5014/ajot.57.5.489] [PMID]

- Riyahi A, Rassafiani M, Hassani Mehraban A, Akbarfahimi M. Functional classification systems for children with cerebral palsy: An ICF-based approach. J Rehabil Sci Res. 2024; 11(3):168-77. [Link]

- Stanley FJ, Blair E, Alberman ED. Cerebral palsies: Epidemiology and causal pathways. London: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Link]

- Dehghan L, Abdolvahab M, Bagheri H, Dalvand H, Faghih-Zadeh S. [Inter rater reliability of Persian version of Gross Motor Function Classification System Expanded and Revised in patients with cerebral palsy (Persian)]. Daneshvar Med. 2020; 18(6):37-44. [Link]

- Riyahi A, Rassafiani M, Akbarfahimi N, Sahaf R, Yazdani F. Cross-cultural validation of the Persian version of the Manual Ability Classification System for children with cerebral palsy. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2013; 20(1):19-24. [DOI:10.12968/ijtr.2013.20.1.19]

- Gorter JW, Rosenbaum PL, Hanna SE, Palisano RJ, Bartlett DJ, Russell DJ, et al. Limb distribution, motor impairment, and functional classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004; 46(7):461-7. [DOI:10.1017/S0012162204000763] [PMID]

- Shi W, Luo R, Jiang HY, Shi YY, Wang Q, Li N, et al. [The relationship between the damages of hand functions and the type of cerebral palsy in children (Chinese)]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2015; 46(6):876-9. [PMID]

- Golubović Š, Slavković S. Manual ability and manual dexterity in children with cerebral palsy. Hippokratia. 2014; 18(4):310-4. [PMID]

- Gajewska E, Sobieska M, Samborski W. Associations between manual abilities, gross motor function, epilepsy, and mental capacity in children with cerebral palsy. Iran J Child Neurol. 2014; 8(2):45-52. [PMID]

- Hidecker MJ, Ho NT, Dodge N, Hurvitz EA, Slaughter J, Workinger MS, et al. Inter-relationships of functional status in cerebral palsy: Analyzing gross motor function, manual ability, and communication function classification systems in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012; 54(8):737-42. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04312.x] [PMID]

- Mutlu A, Akmese PP, Gunel MK, Karahan S, Livanelioglu A. The importance of motor functional levels from the activity limitation perspective of ICF in children with cerebral palsy. Int J Rehabil Res. 2010; 33(4):319-24. [DOI:10.1097/MRR.0b013e32833abe71] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 2025/02/8 | Accepted: 2025/05/5 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2025/02/8 | Accepted: 2025/05/5 | Published: 2025/03/2