Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nayak S S, Maharana S, Behera D. Efficacy of a Modified Hip Abduction Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip Orthosis in Children: A Case Study. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-300-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-300-en.html

1- Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Swami Vivekanand National Institute of Rehabilitation Training and Research, Cuttack, India. , id-lollybpo@gmail.com

2- Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Swami Vivekanand National Institute of Rehabilitation Training and Research, Cuttack, India.

2- Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Swami Vivekanand National Institute of Rehabilitation Training and Research, Cuttack, India.

Keywords: Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), Containment mechanics, Flexion, Controlled abduction orthosis

Full-Text [PDF 2752 kb]

(69 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (236 Views)

Full-Text: (64 Views)

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a relatively common hip disorder in children, affecting 1–3% of all newborns [1]. Additionally, DDH, previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, is a common issue that affects the hip joint in babies and children. It happens when the femoral head (the ball) does not properly fit into the acetabulum (the socket) of the pelvis, which can cause the hip joint to be unstable or dislocated. More precisely, this issue can occur when a baby is born or is in the first few months of life, implying that the hip can dislocate on its own during, before, or shortly after birth. The acetabulum (the socket) may not develop correctly, causing the femoral head to slip partially or completely out of the hip joint. This condition encompasses a range of hip problems, including hips with dysplasia that are stable, partially dislocated hips, and completely dislocated hips [2].

According to research on hip dysplasia, the presence of residual hip dysplasia in the X-rays of patients can be a sign of degenerative joint disease [3]. Stulberg et al. found that nearly half of patients with hip joint disease also had primary acetabular dysplasia (PAD) [4]. Severe subluxation is closely linked to degenerative joint disease, and the severity of subluxation is related to when symptoms first appear [5]. Severe subluxation symptoms typically start during the teenage years.

Approximately 1 out of every 1000 individuals is estimated to suffer from DDH. Girls are more affected than boys, with about 80% of cases occurring in girls. The incidence of dysplasia is approximately 1 in 100, and that of dislocation is approximately 1 in 1000. The left hip is more commonly affected, with 60%, 20%, and 20% of cases involving the left hip, the right hip, and both hips, respectively. DDH is more common in females, with a ratio of around 6 females to 1 male. The increased risk in females is believed to be due to several factors, such as hereditary predisposition to joint laxity, hormone-induced joint laxity, breech malposition, or genetic causes. The risk factors are higher in firstborn babies, especially female children.

Its signs and symptoms in a newborn include shorter legs, uneven skin folds, limited hip abduction (difficulty spreading the legs), and a clicking sound during hip movement. Similarly, in older infants, they include Trendelenburg gait, limping or waddling, leg length discrepancy, and increased lumbar lordosis in bilateral dislocation.

Due to variations in limb length, unilateral dislocations are more likely to result in symptoms than bilateral ones, including problems with the knee and back. However, even bilateral dislocations can cause back pain, possibly due to excessive arching of the lower back [6].

Identifying DDH involves checking for symptoms and using imaging tests. Doctors typically examine newborns and children for factors that may predispose them to hip problems.

The examination includes performing tests, such as the Ortolani test and the Barlow maneuver, as well as assessing for signs, including limited hip movement, uneven gluteal folds, or differences in leg length, which may indicate possible hip dysplasia.

Doctors should follow up on any unusual results from a clinical screening by performing X-rays or ultrasounds, depending on the patient’s age [7, 8]. Identifying and treating issues early can help avoid problems such as ongoing dislocation and hip osteoarthritis [9]. More precisely, the accurate and timely detection of this condition is critical, with diagnostic methods traditionally relying on clinical examinations. However, advancements in medical imaging (e.g. ultrasound) have prompted research into more effective screening strategies. Universal ultrasound screening incurs higher initial costs; it is more effective in detecting cases of hip dysplasia early, which can lead to timely interventions and potentially reduce the need for more invasive and costly treatments later (e.g. surgical corrections). This finding aligns with the broader literature, which emphasizes the importance of early detection in improving outcomes for DDH [10].

DDH treatment varies depending on the severity of problems and the age of patients. It may involve basic treatments, such as modifying activities, participating in physical therapy, and wearing splints, or more advanced options, including surgery [11, 12]. Considering that there is no concrete proof that one surgical strategy is superior to the others, the management is chosen based on the surgeon’s preferences and the overall clinical picture [7, 8].

Premature arthrosis and long-term hip deformities with gait abnormalities may occur if DDH is ignored and or not treated [13]. When hip dysplasia is diagnosed, conservative treatment typically involves the use of a flexion-abduction orthosis [14, 15]. Regardless of design variations, each orthosis shares a common feature: It “flexes and spreads” [16]. Due to this situation, the femoral head becomes centralized in the acetabulum, ultimately resulting in a physiological (post-)maturing [15, 16]. The alleviation of pressure, especially in the anterior acetabular area, leads to an increased potential for osseous and cartilaginous reorganization [14, 16, 17-20]. Various orthoses are utilized for treating DDH, and their therapeutic results are comparable when the Graf-type dislocation and treatment principle (hip abduction and flexion) remains consistent. The long-term effects on an infant’s axial skeleton have not been investigated yet.

When treating DDH in an otherwise healthy child, the objectives include achieving concentric reduction of the hip, maintaining the decrease, and ensuring the regular development of the acetabulum and femoral head. The other objectives are to prevent treatment complications (e.g. stiffness, infection, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and femoral nerve palsy) and to prevent unnecessary suffering for patients and their parents, whether physical, emotional, or financial [6]. For the optimal reduction of the femoral head, it should be positioned in a flexed and abducted position. Nevertheless, extreme positions can lead to several complications, such as deep flexion resulting in femoral nerve palsies, and wide abduction and or excessive internal rotation, leading to avascular necrosis.

The Frejka pillow, Pavlik harness, Tübingen hip orthosis, von Rosen orthosis, Ilfeld orthosis, semirigid Plastazote hip abduction orthoses, and Camp Dynamic Hip Abduction Orthosis are among the conservative treatments for DDH. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of a modified design of the hip abduction DDH orthosis in better containing the femoral head within the acetabulum through a mechanical device or orthosis.

Case Presentation

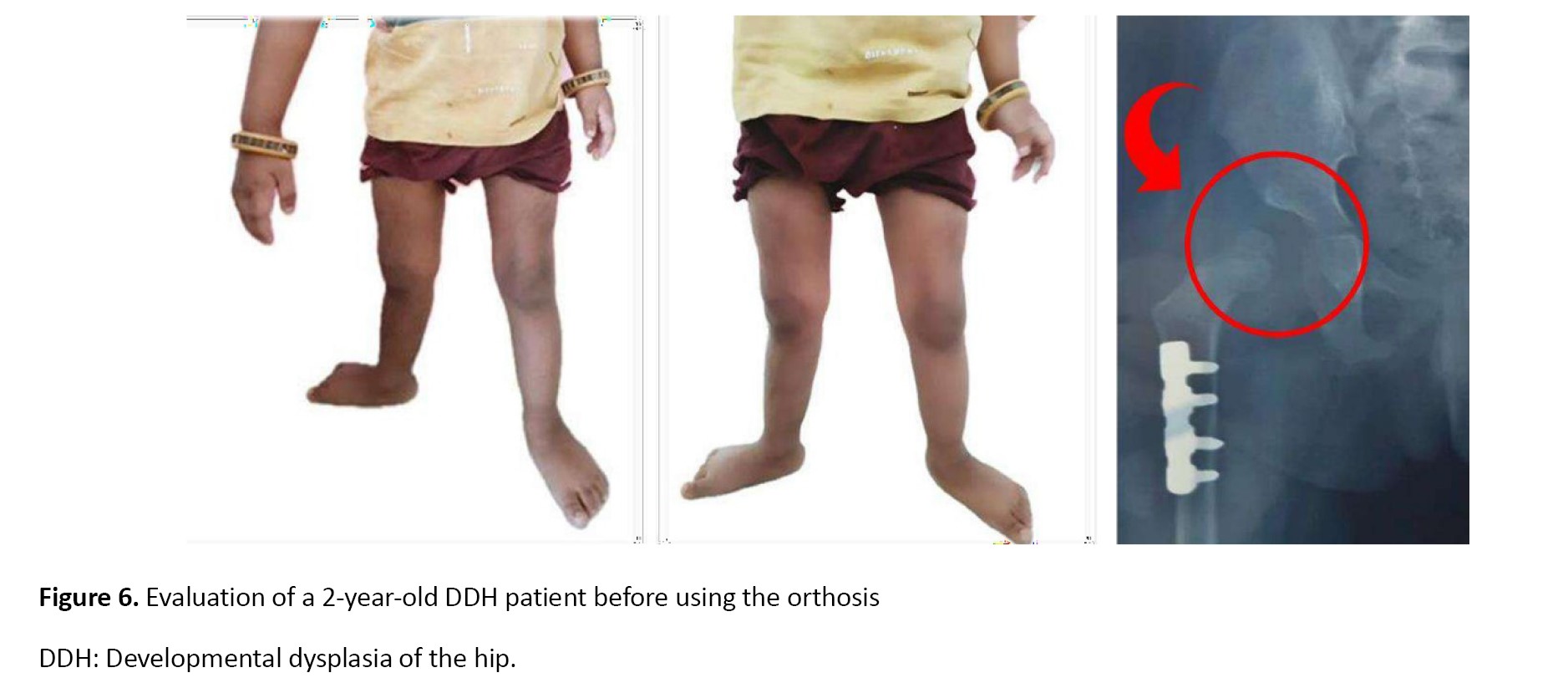

A 2-year-old female patient presented with DDH, diagnosed since birth. Her parents expressed concerns about her gait and asymmetrical posture, specifically noting a limp while walking and a limited range of motion in her right hip. However, no other congenital anomalies were reported, and no previous treatments had been provided until this evaluation. The child’s parents were concerned about her delayed motor development and gait instability. Therefore, they referred to our institute, SVNIRTAR, Cuttack, for orthopedic assessment and proper management.

Upon physical examination, the left hip showed limited abduction, with asymmetry in the hip level observed during gait analysis. With the left leg appearing shorter, a discrepancy in leg length was evident. Barlow and Ortolani tests were positive, indicating hip instability. A noticeable telescoping sign was observed as well. Based on these findings, the patient underwent a further evaluation with a plain radiographic study of the pelvis to determine the nature and severity of the DDH.

Study tools and outcome measures

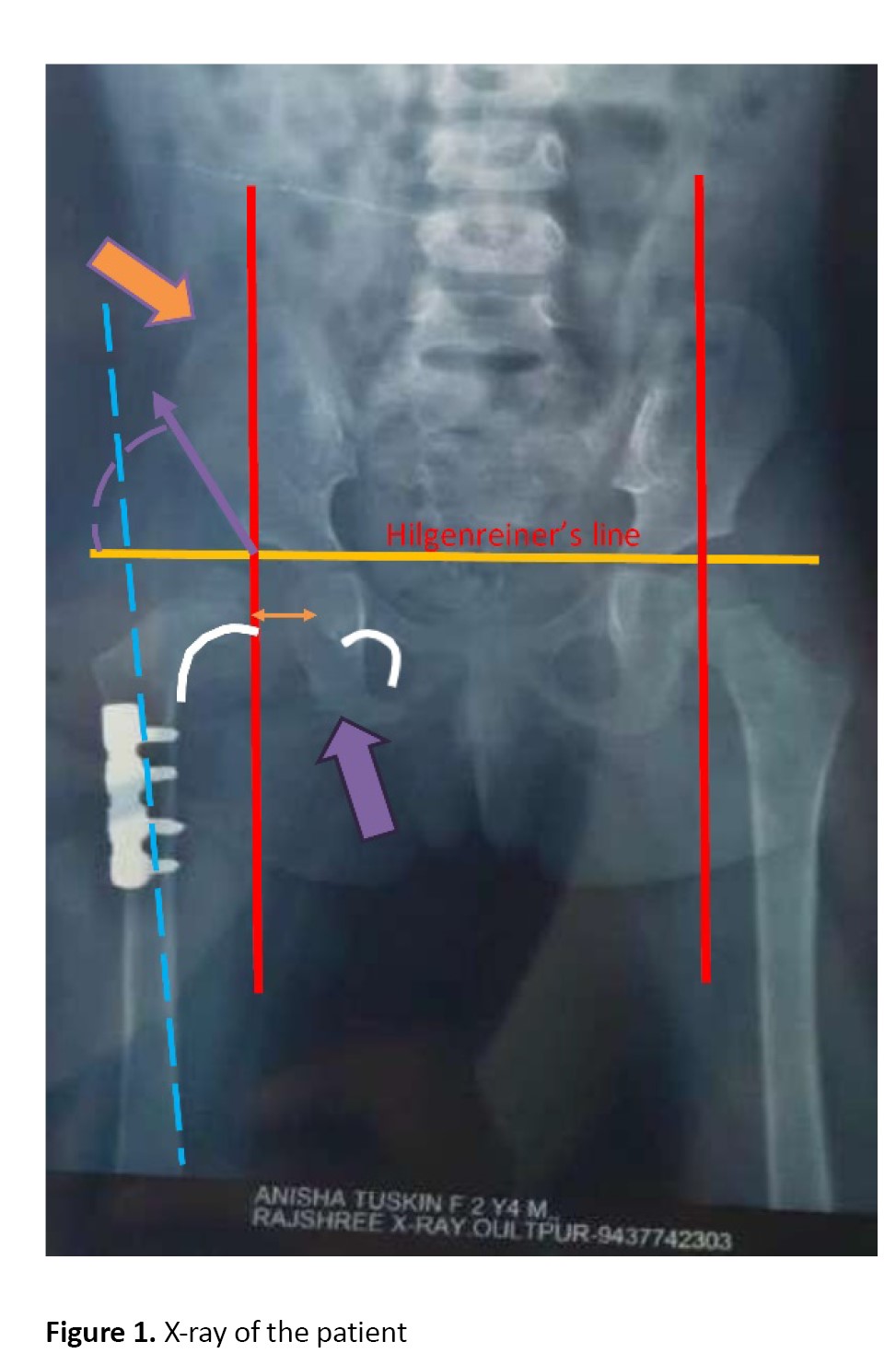

Radiographs (Figure 1) revealed the right AD with a measured acetabular angle of 40°, confirming DDH with a high subluxation risk. A femoral head with significant displacement was observed as well. Based on the findings, the femoral metaphysis lay lateral to Parkin’s line, and Shenton’s line was broken. In addition, lateral displacement of the femoral head, an increased medial gap, delayed appearance of the center of ossification of the femoral head, hypoplasia of the pelvic (ilium), delayed fusion of the ischiopubic junction, adducted femur, and an increased acetabular index (AI) were detectable. No other skeletal abnormalities were present, and the child was otherwise healthy.

The orthopedic team discussed treatment options with the parents, aiming to promote hip stability, prevent joint degeneration and complications, and restore normal gait mechanics and leg length symmetry.

After discussing the potential risks and benefits, the clinic team recommended initiating treatment with a modified hip abduction orthosis featuring a biaxial hip joint, allowing for gradual reduction and stabilization, as well as hip mobilization. The treatment plan further included a program of physiotherapy to promote the range of motion and correct positioning during hip development. Parents were educated on the correct use of orthoses and advised to return for further follow-ups at 3-month intervals, with radiographic re-evaluation of hip position and acetabular development.

Orthosis description

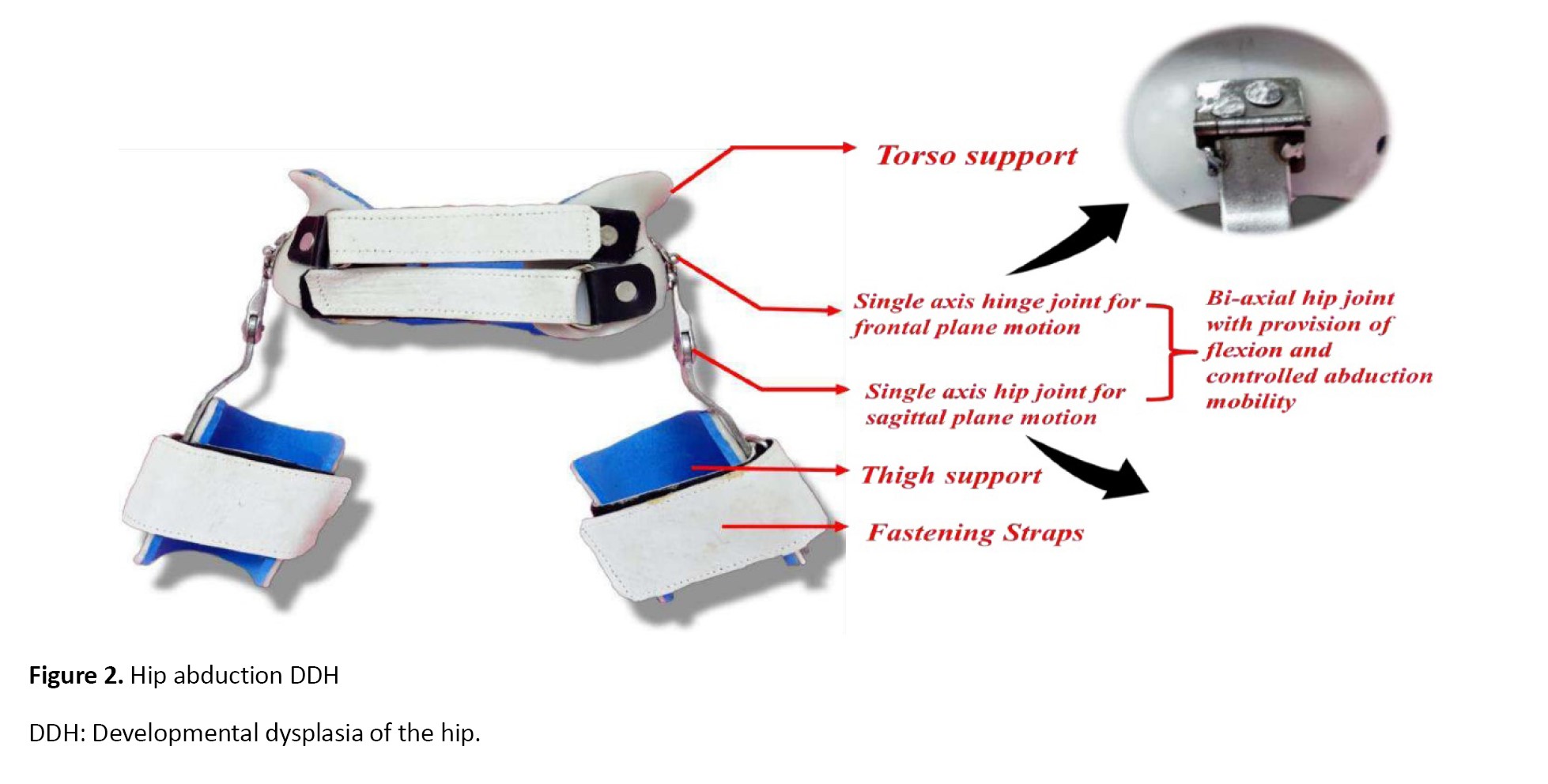

The hip abduction DDH orthosis (Figure 2), which is custom-made and modified, includes a torso support composed of 4 mm polypropylene and features adjustable straps affixed to the front. The superior trim lines of torso support extend from a point ½ inches above the iliac crest. In addition, the inferior trimline reaches the apex of the gluteal bulge, providing sufficient clearance for sitting.

The torso support is linked to bilateral thigh cuffs via a biaxial hip joint. Soft Etha flex padding lines the thigh cuffs for added comfort and to prevent skin irritation. On the other hand, each thigh cuff connects to the pelvic band through a biaxial hip joint. This joint allows for regulated movements in two planes, thereby offering flexion and controlled abduction mobility. The single-axis hinge joint permits motion in the frontal plane. In contrast, the single-axis hip joint allows for motion in the sagittal plane, thereby facilitating the maintenance of an abducted hip position without completely restricting hip movement. The orthosis is primarily intended to encapsulate the femoral head within the acetabulum while preserving the acetabular labrum.

Functionality

This orthosis maintains the hips in an abducted position, a critical aspect of DDH treatment that helps the femoral head remain within the acetabulum. The biaxial joints allow for gradual, controlled movements, which can aid in hip stabilization and help the femoral head develop within the acetabulum more naturally. The design also promotes compliance by allowing a degree of comfort and mobility, making it more tolerable for children to wear over an extended period.

Planning and construction

The torso and thigh support (Figure 3) are made from rigid materials, such as polypropylene or thermoplastic, which provide stabilization. The inner padding is typically made of Ethaflex to prevent skin irritation and ensure comfort. The measure and casting of the torso and thighs to fabricate the proper-sized support.

The device features bi-axial hip joints that allow for controlled motion in both the frontal and sagittal planes, as well as flexion and controlled abduction. The hinges should be designed with stainless steel to ensure durability and ease of movement. The hinge joints should be carefully aligned to allow abduction/adduction and flexion/extension. Polypropylene sheet, Ethaflex, a hinge joint, and stainless steel were used in the fabrication process.

Fabrication process

For this purpose, a mold of the patient’s torso is created through casting, and precise measurements are used to design the customized support. After casting, the negative cast is poured to form a positive modified mold. Then, the mold is biomechanically modified, and the thermoplastic material is heated and vacuum-formed over the mold to form the rigid base. The edges are trimmed and smoothed to avoid discomfort or irritation.

Similar to the torso support, the thigh cuffs are molded and formed using thermoplastic or polypropylene. Then, foam padding is added for comfort, and the edges are smoothed.

A size-1 single-axis hip joint is taken for frontal and sagittal plane motions, and a small hinge joint is welded at the proximal end of the joint uprights. As a result, it acts as a bi-axial joint for the hip, allowing for flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. Then, the hinges are correctly aligned over the torso support, with respect to the anatomical hip joint, to allow smooth, controlled movements without impinging.

Next, the lower upright of the hip joint is attached to the thigh shell. The upright is bent with a proper abduction angle. After fabrication, the orthosis should be fitted to the patient, ensuring that all moving parts operate smoothly. Adjustable straps are attached using rivets to secure the orthosis onto the torso. Additionally, the straps and joint alignments are adjusted as needed for optimal comfort and function.

Biomechanics of the orthosis

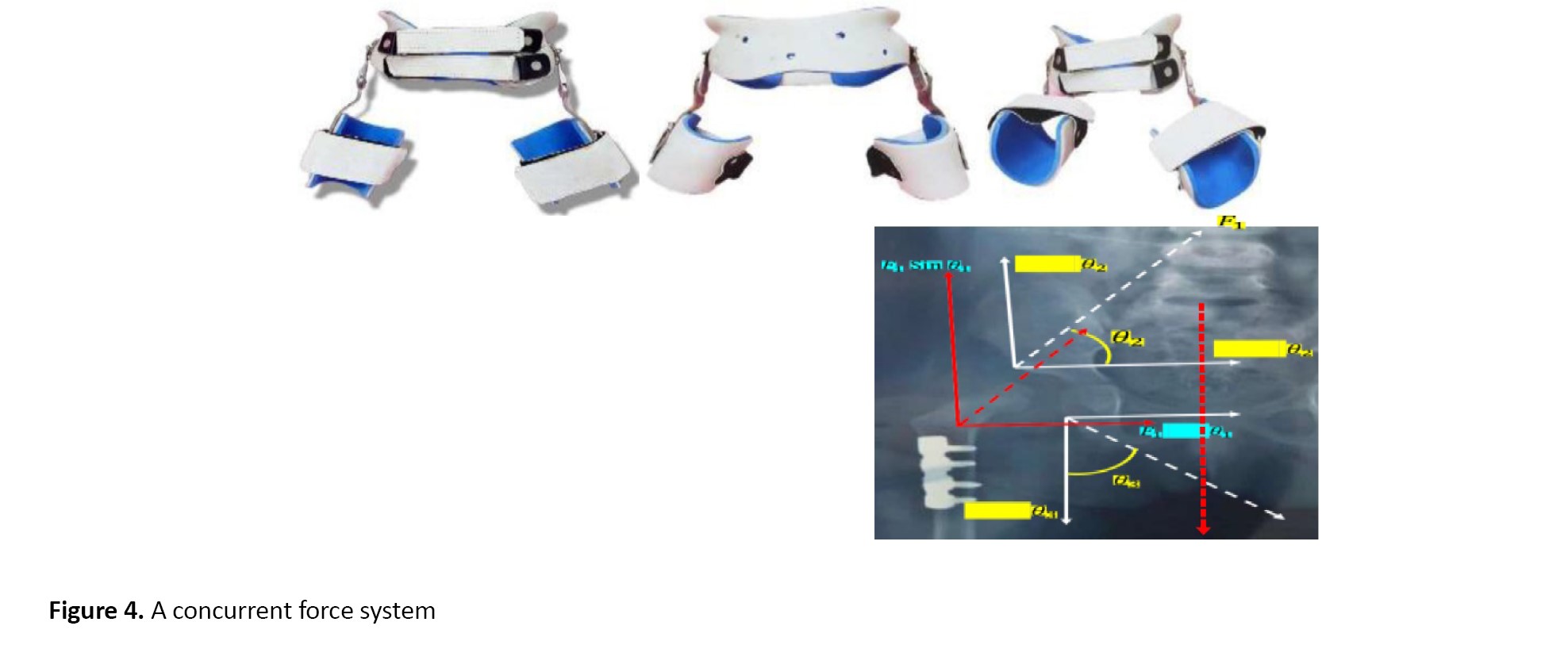

The principle of the concurrent force system underlies the biomechanics of a hip abduction orthosis designed for DDH. The concept is that the force exerted by the orthosis will collaborate with the anatomical forces at play on the hip joint to reach a desired result. In this force system, the lines of action of all forces intersect at a single point [8]. A concurrent force system, in this context, refers to the situation where several forces are simultaneously acting on the hip joint and collaborating to establish stability.

The principle underlying this system (Figure 4) is the biomechanics of a hip abduction orthosis designed for DDH. The concept is that the force exerted by the orthosis will collaborate with the anatomical forces at play on the hip joint to reach a desired result. In this system, the lines of action of all forces intersect at a single point [8]. A concurrent force system, in this context, refers to the situation where several forces are simultaneously acting on the hip joint and collaborating to establish stability. The hip abduction orthosis provides an external force that aligns with anatomical forces (e.g. the muscle and ligament forces around the hip joint) to keep the femoral head securely within the acetabulum (the hip socket).

The hip joint is a bi-axial joint, allowing motion in two primary planes of motion. To stabilize it in abduction, the orthosis applies forces in the vertical and horizontal directions.

Basically, two concurrent force couples act just above and below the hip joint. The bi-axial hip joint is concurrent with the lateral force. Thereby, the vertical component (Sin θ components) of relaxation is multiplied by the opposite force (Equation 1). Thus:

1. F Sin θ1-F Sin θ2=0

However, the horizontal component is aggregated as 2 Cos(θ1 θ2); as a result, it causes snug-fitting capsulation within the cavity (Equation 2). Hence:

2. F=F Cos θ1+F Cos θ2

Now, there is another force couple, applied by the orthosis, that is, θ1 Sin θ1 & θ1 Cos θ1.

Again, the vertical component gets canceled out by the total weight (W); as a result, the horizontal component is responsible for the encapsulation of the hip joint (Equation 3). Accordingly:

3. Total force=F1 Cos θ1+F2 Cos θ2+F3 Cos θ3

F1 Sin θ1=W

Mechanism of the modified device

The modified device operates through a bi-axial mechanical hip joint that facilitates femoral abduction, allowing for a more natural range of motion in the hip (Figure 5). Enhanced containment is achieved by the relative abduction of the femur, which works in tandem with the moment of inertia to stabilize the limb. Vertical traction, exerted by the torso, provides additional support and aids in controlled rotation, thereby optimizing the stability of the device during use. Furthermore, the mechanical hip joint allows for necessary flexion and a limited degree of extension, thereby enabling active ambulation while maintaining stability and support.

Evaluation of the force system

Evaluating the force system involves assessing three primary forces. The abduction force pushes the femur outward while pulling the femoral head upward against the socket, thereby promoting proper alignment. The containment force, applied by straps or a pad, generates a gentle inward force to secure the limb in place. Finally, the countertraction force, exerted by the torso, creates an upward pull that balances the downward pressure, contributing to overall stability and support within the socket.

Impact of the orthosis

The capitular sulcus is more developed, with proper reduction of avulsion. This controlled dysplasia reduces stress on the spine, thus minimizing the risk of developing excessive lordosis, kyphosis, or scoliosis (Figures 6 and 7). A well-executed reduction of avulsion can significantly impact spinal health by managing controlled dysplasia. This control minimizes undue stress on the spine, effectively reducing the risk of other conditions (e.g. lordosis or kyphosis) and lowering the likelihood of scoliosis development.

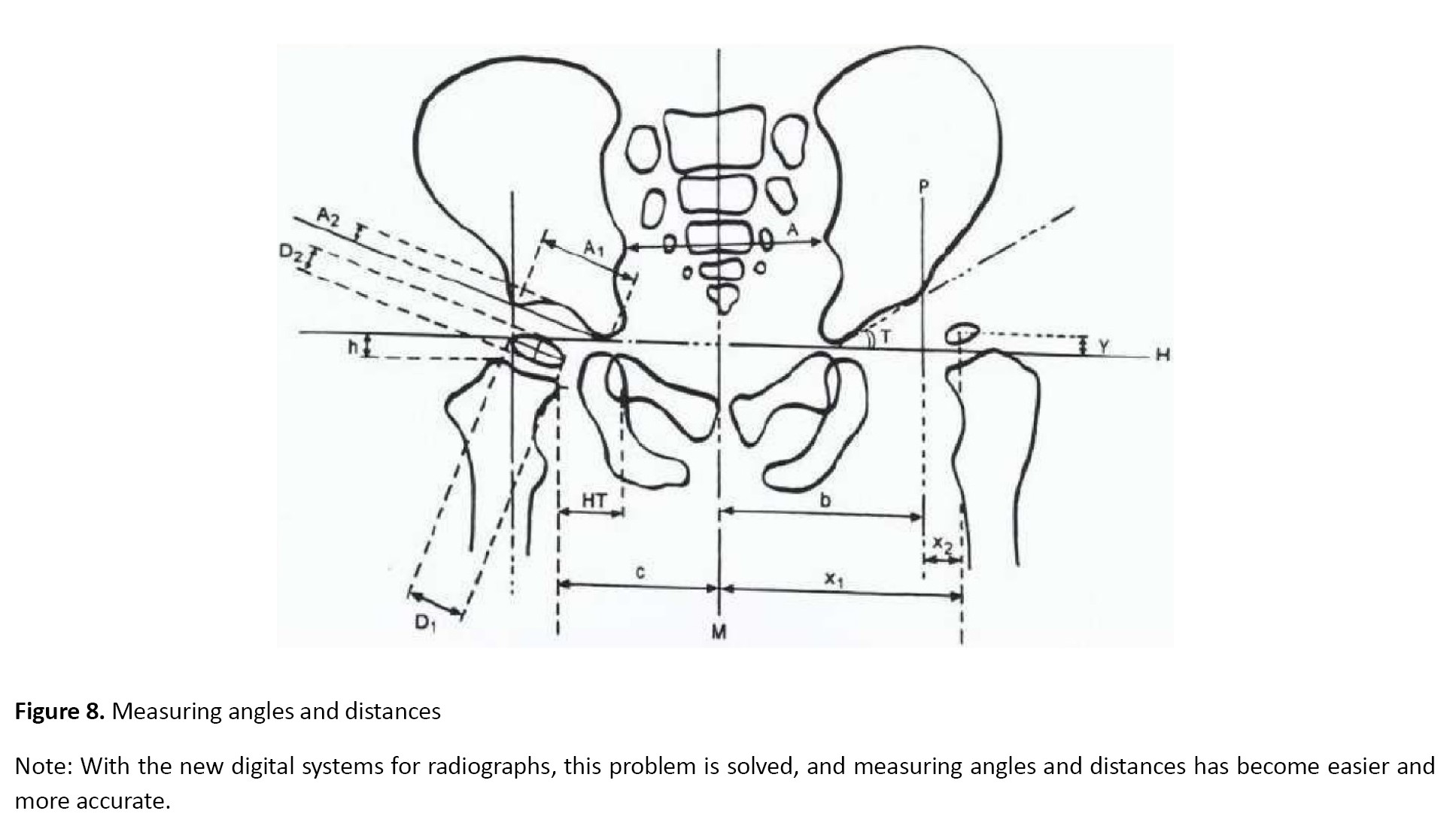

The following measurements (steps 1–14) and two ratios were utilized, with measurements in mm and angles in degrees (Figure 8). Initially, a vertical line representing the midline (M) is drawn through the sacrum and the symphysis pubis. Subsequently, the Hilgenreiner’s horizontal line (H) is drawn through the triradiate cartilage at the lowest point of the ilium. In addition, the Perkins’ line (P) is established at a right angle to the H-line at the edge of the bony acetabulum. Then the following lines were drawn:

The distance from the midpoint of the ossification center of the femoral head to the midline (X1), the distance from the center of the ossific nucleus of the femoral head to the P-line (X2) measured at a negative value when it is lateral to the P-line, the distance from the center of the ossific nucleus of the femoral head to the H-line (indicated as a negative value when it is above the H-line) (Y), The width of the acetabular edge and the ossific nucleus of the femoral head (D1), the height of the femoral head ossific nucleus (D2), the distance from the most medial proximal femoral metaphysis to the midline (c), the distance from the most superior point of the proximal femoral metaphysis to the H-line (a negative value if above the H-line) (h), abstand modified head-tear (HT) drop, abstands von der P-Linie zur Mittellinie (b), A1: Acetabular length, and A2: Acetabular depth.

The acetabular angle (in degrees) is the angle between the H-line and the line that connects the lowest point of the ilium to the acetabular edge.

The ratio is calculated by measuring the distance from the most medial femoral metaphysis to the midline and from the P-line to the midline (known as Smith’s c/b ratio for lateral or horizontal displacement).

Another ratio is determined by measuring the distance from the most superior femoral metaphysis to the H-line and from the P-line to the midline (known as Smith’s h/b ratio for superior or vertical migration).

Results

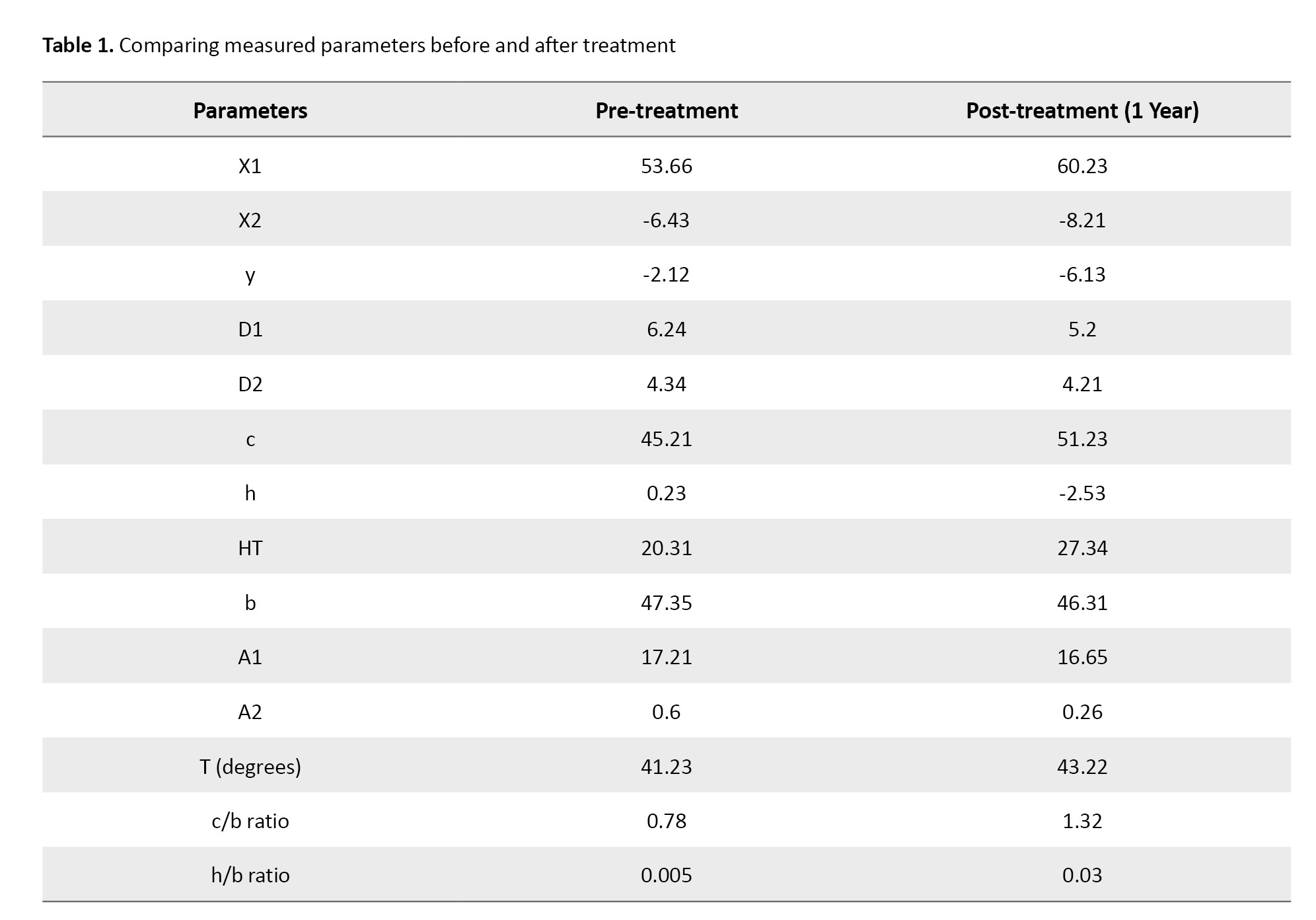

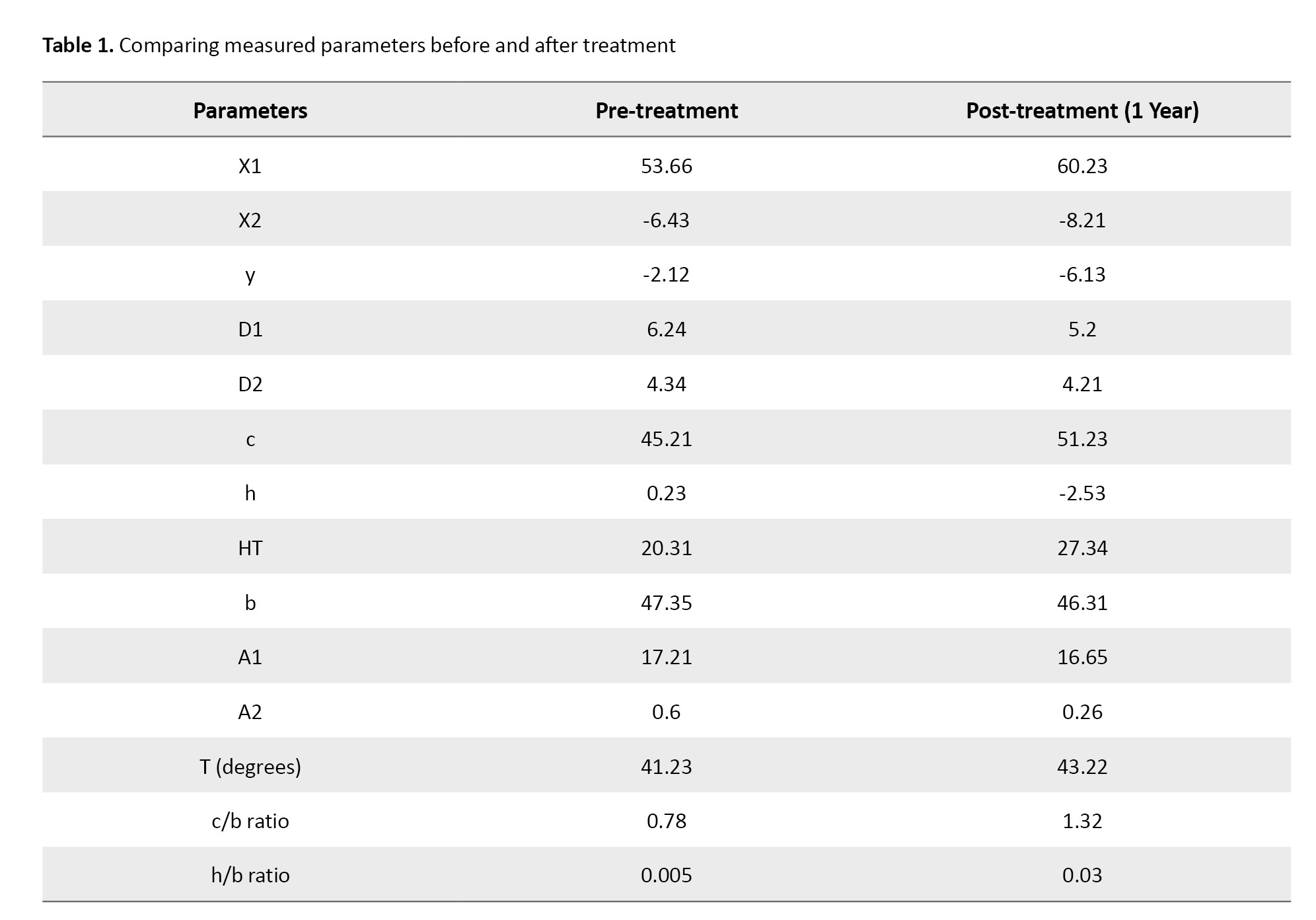

The results demonstrated an improvement in joint alignment and enhanced stabilization of the hip joint, contributing to decreased laxity in the capsule and ligament (Table 1).

These effects could promote healthy cartilage development and facilitate the formation of the capitular sulcus. Moreover, the intervention had a preventative role against complications such as kyphosis, leg length discrepancy, and osteoarthritis. Overall, these outcomes supported improved quality of life and functional performance in the individuals involved.

Discussion

It is important to be careful about treating DDH since a risk of nutritional problems in the hip joint accompanying it. Using orthotic treatment is best for kids under 6 months old, as it can interfere with hip growth later on. If parents do not cooperate, it can lead to complications or reduce the effectiveness of the treatment [21]. Doctors believe that bracing is the best way to treat DDH in babies under 6 months old with hips that can be fixed. The baby’s hip with DDH needs to stay in a safe position with 100° flexion and abduction that is not more than 60°. A review of bracing revealed that dynamic bracing is typically worn full-time for approximately 16.4 weeks, while static bracing is worn for around 8.9 weeks [22, 23]. Reductions were achieved in this case. The new design gradually fixes the problem over time until it is fully resolved. This finding indicates that the patient is satisfied with the orthosis. A rigid brace helps keep the hips in a straighter position than a standard Pavlik harness and can prevent dislocations by securely holding the hip in place [24, 25].

The brace was created to help doctors, parents, and children deal with DDH more easily in their daily lives. It is made of lightweight, flexible material, making it simple for parents to use every day. Additionally, our brace lets babies sit comfortably. Furthermore, adjusting the brace during treatment is easily accomplished by gently heating and shaping the thermoplastic material into the right position. The goal of using splints is to fix the hip’s position and promote proper joint development.

Köse et al. evaluated the effectiveness of abduction orthosis in treating primary AD [26]. They found that its use led to significant improvements in AI values, suggesting that early intervention is crucial for patients with primary AD. It is worth noting that dysplastic hips improved more in AI than non-dysplastic hips within the first 6 months of therapy. This outcome aligns with the quicker improvement observed in our study during the initial treatment phase.

Specialists debate the best time for treatment between 6 months old and 18 months old. The Pavlik harness is less effective after 6 months, so doctors suggest pelvic osteotomy after 18 months old. Waiting for the hip socket to develop on its own as the child grows older is impractical since delaying treatment can lead to more severe cases of hip dysplasia. Spontaneous resolution is unlikely [27]. Although the Pavlik harness is a reliable method for treating DDH, its effectiveness may decline in babies over six months old, particularly those over four months old. When the Pavlik harness does not give acceptable results in older and more active children, doctors often use an abduction orthosis instead. There is limited information available on the use of abduction orthoses to treat AD. Gans et al evaluated babies with stable DDH who had been treated but still had AD at 6 months old. They observed that using bracing when the 6-month x-ray shows an AI greater than 30 degrees helps improve the AI between 6 months and 12 months of age more effectively than just watching or using the Pavlik harness [28].

Radiological parameters have proven to be invaluable in the diagnosis and management of DDH. Several measurements have been employed to aid in the radiographic evaluation of DDH. The findings of this research corroborate the potential usefulness of different radiographic measurements in determining treatment methods for DDH cases in children aged 12–24 months [29].

According to the most recent studies, employing specific radiographic measurements in cases of DDH may aid in decision-making regarding whether conservative or surgical treatment is warranted. The ossific nucleus of the femoral head (D1) was found to have a greater width in cases of conservative treatment, indicating that a larger nucleus size at the first evaluation correlates with higher success rates for conservative treatment among individuals of the same age group. This study identified measurements from pre-reduction radiographs as the best indicators for the need for operative treatment after CR: femoral head lateralization (X1, c, HT, and c/b ratio), superior migration of the femoral head (Y, h, and h/b ratio), and an acetabular angle (T).

Conclusion

In general, the x-ray results indicated that the avulsion reduction achieved with this intervention closely approaches normal alignment, promoting proper encapsulation. This newly designed, modified articulated orthosis not only corrects the deformity effectively but also allows for the restoration of normal functional movement. Yet, using an abduction orthosis is a safe and effective way to possibly lower the chances of suffering from osteoarthritis at a young age and avoid the need for surgery later on. Further research is needed to determine the duration for which the orthosis remains effective and should be worn.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics at Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, India (Code: 10211).

Funding

This paper has been derived from a research project supported by and conducted at Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, India.

Authors' contributions

Methodology and conceptualization: Sushree Sangita Nayak, Srikanta Maharana, and Debashis Behera; Investigation and data curation: Sushree Sangita Nayak and Debashis Behera; Validation and formal analysis: Sushree Sangita Nayak and Srikanta Maharana; Project administration: Srikanta Maharana; Supervision and resources: Debashis Behera and Srikanta Maharana; Visualization and writing the original draft: Sushree Sangita Nayak; Review, and editing: Srikanta Maharana and Debashis Behera.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for her timely cooperation and sincere participation in this study.

References

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a relatively common hip disorder in children, affecting 1–3% of all newborns [1]. Additionally, DDH, previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, is a common issue that affects the hip joint in babies and children. It happens when the femoral head (the ball) does not properly fit into the acetabulum (the socket) of the pelvis, which can cause the hip joint to be unstable or dislocated. More precisely, this issue can occur when a baby is born or is in the first few months of life, implying that the hip can dislocate on its own during, before, or shortly after birth. The acetabulum (the socket) may not develop correctly, causing the femoral head to slip partially or completely out of the hip joint. This condition encompasses a range of hip problems, including hips with dysplasia that are stable, partially dislocated hips, and completely dislocated hips [2].

According to research on hip dysplasia, the presence of residual hip dysplasia in the X-rays of patients can be a sign of degenerative joint disease [3]. Stulberg et al. found that nearly half of patients with hip joint disease also had primary acetabular dysplasia (PAD) [4]. Severe subluxation is closely linked to degenerative joint disease, and the severity of subluxation is related to when symptoms first appear [5]. Severe subluxation symptoms typically start during the teenage years.

Approximately 1 out of every 1000 individuals is estimated to suffer from DDH. Girls are more affected than boys, with about 80% of cases occurring in girls. The incidence of dysplasia is approximately 1 in 100, and that of dislocation is approximately 1 in 1000. The left hip is more commonly affected, with 60%, 20%, and 20% of cases involving the left hip, the right hip, and both hips, respectively. DDH is more common in females, with a ratio of around 6 females to 1 male. The increased risk in females is believed to be due to several factors, such as hereditary predisposition to joint laxity, hormone-induced joint laxity, breech malposition, or genetic causes. The risk factors are higher in firstborn babies, especially female children.

Its signs and symptoms in a newborn include shorter legs, uneven skin folds, limited hip abduction (difficulty spreading the legs), and a clicking sound during hip movement. Similarly, in older infants, they include Trendelenburg gait, limping or waddling, leg length discrepancy, and increased lumbar lordosis in bilateral dislocation.

Due to variations in limb length, unilateral dislocations are more likely to result in symptoms than bilateral ones, including problems with the knee and back. However, even bilateral dislocations can cause back pain, possibly due to excessive arching of the lower back [6].

Identifying DDH involves checking for symptoms and using imaging tests. Doctors typically examine newborns and children for factors that may predispose them to hip problems.

The examination includes performing tests, such as the Ortolani test and the Barlow maneuver, as well as assessing for signs, including limited hip movement, uneven gluteal folds, or differences in leg length, which may indicate possible hip dysplasia.

Doctors should follow up on any unusual results from a clinical screening by performing X-rays or ultrasounds, depending on the patient’s age [7, 8]. Identifying and treating issues early can help avoid problems such as ongoing dislocation and hip osteoarthritis [9]. More precisely, the accurate and timely detection of this condition is critical, with diagnostic methods traditionally relying on clinical examinations. However, advancements in medical imaging (e.g. ultrasound) have prompted research into more effective screening strategies. Universal ultrasound screening incurs higher initial costs; it is more effective in detecting cases of hip dysplasia early, which can lead to timely interventions and potentially reduce the need for more invasive and costly treatments later (e.g. surgical corrections). This finding aligns with the broader literature, which emphasizes the importance of early detection in improving outcomes for DDH [10].

DDH treatment varies depending on the severity of problems and the age of patients. It may involve basic treatments, such as modifying activities, participating in physical therapy, and wearing splints, or more advanced options, including surgery [11, 12]. Considering that there is no concrete proof that one surgical strategy is superior to the others, the management is chosen based on the surgeon’s preferences and the overall clinical picture [7, 8].

Premature arthrosis and long-term hip deformities with gait abnormalities may occur if DDH is ignored and or not treated [13]. When hip dysplasia is diagnosed, conservative treatment typically involves the use of a flexion-abduction orthosis [14, 15]. Regardless of design variations, each orthosis shares a common feature: It “flexes and spreads” [16]. Due to this situation, the femoral head becomes centralized in the acetabulum, ultimately resulting in a physiological (post-)maturing [15, 16]. The alleviation of pressure, especially in the anterior acetabular area, leads to an increased potential for osseous and cartilaginous reorganization [14, 16, 17-20]. Various orthoses are utilized for treating DDH, and their therapeutic results are comparable when the Graf-type dislocation and treatment principle (hip abduction and flexion) remains consistent. The long-term effects on an infant’s axial skeleton have not been investigated yet.

When treating DDH in an otherwise healthy child, the objectives include achieving concentric reduction of the hip, maintaining the decrease, and ensuring the regular development of the acetabulum and femoral head. The other objectives are to prevent treatment complications (e.g. stiffness, infection, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and femoral nerve palsy) and to prevent unnecessary suffering for patients and their parents, whether physical, emotional, or financial [6]. For the optimal reduction of the femoral head, it should be positioned in a flexed and abducted position. Nevertheless, extreme positions can lead to several complications, such as deep flexion resulting in femoral nerve palsies, and wide abduction and or excessive internal rotation, leading to avascular necrosis.

The Frejka pillow, Pavlik harness, Tübingen hip orthosis, von Rosen orthosis, Ilfeld orthosis, semirigid Plastazote hip abduction orthoses, and Camp Dynamic Hip Abduction Orthosis are among the conservative treatments for DDH. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of a modified design of the hip abduction DDH orthosis in better containing the femoral head within the acetabulum through a mechanical device or orthosis.

Case Presentation

A 2-year-old female patient presented with DDH, diagnosed since birth. Her parents expressed concerns about her gait and asymmetrical posture, specifically noting a limp while walking and a limited range of motion in her right hip. However, no other congenital anomalies were reported, and no previous treatments had been provided until this evaluation. The child’s parents were concerned about her delayed motor development and gait instability. Therefore, they referred to our institute, SVNIRTAR, Cuttack, for orthopedic assessment and proper management.

Upon physical examination, the left hip showed limited abduction, with asymmetry in the hip level observed during gait analysis. With the left leg appearing shorter, a discrepancy in leg length was evident. Barlow and Ortolani tests were positive, indicating hip instability. A noticeable telescoping sign was observed as well. Based on these findings, the patient underwent a further evaluation with a plain radiographic study of the pelvis to determine the nature and severity of the DDH.

Study tools and outcome measures

Radiographs (Figure 1) revealed the right AD with a measured acetabular angle of 40°, confirming DDH with a high subluxation risk. A femoral head with significant displacement was observed as well. Based on the findings, the femoral metaphysis lay lateral to Parkin’s line, and Shenton’s line was broken. In addition, lateral displacement of the femoral head, an increased medial gap, delayed appearance of the center of ossification of the femoral head, hypoplasia of the pelvic (ilium), delayed fusion of the ischiopubic junction, adducted femur, and an increased acetabular index (AI) were detectable. No other skeletal abnormalities were present, and the child was otherwise healthy.

The orthopedic team discussed treatment options with the parents, aiming to promote hip stability, prevent joint degeneration and complications, and restore normal gait mechanics and leg length symmetry.

After discussing the potential risks and benefits, the clinic team recommended initiating treatment with a modified hip abduction orthosis featuring a biaxial hip joint, allowing for gradual reduction and stabilization, as well as hip mobilization. The treatment plan further included a program of physiotherapy to promote the range of motion and correct positioning during hip development. Parents were educated on the correct use of orthoses and advised to return for further follow-ups at 3-month intervals, with radiographic re-evaluation of hip position and acetabular development.

Orthosis description

The hip abduction DDH orthosis (Figure 2), which is custom-made and modified, includes a torso support composed of 4 mm polypropylene and features adjustable straps affixed to the front. The superior trim lines of torso support extend from a point ½ inches above the iliac crest. In addition, the inferior trimline reaches the apex of the gluteal bulge, providing sufficient clearance for sitting.

The torso support is linked to bilateral thigh cuffs via a biaxial hip joint. Soft Etha flex padding lines the thigh cuffs for added comfort and to prevent skin irritation. On the other hand, each thigh cuff connects to the pelvic band through a biaxial hip joint. This joint allows for regulated movements in two planes, thereby offering flexion and controlled abduction mobility. The single-axis hinge joint permits motion in the frontal plane. In contrast, the single-axis hip joint allows for motion in the sagittal plane, thereby facilitating the maintenance of an abducted hip position without completely restricting hip movement. The orthosis is primarily intended to encapsulate the femoral head within the acetabulum while preserving the acetabular labrum.

Functionality

This orthosis maintains the hips in an abducted position, a critical aspect of DDH treatment that helps the femoral head remain within the acetabulum. The biaxial joints allow for gradual, controlled movements, which can aid in hip stabilization and help the femoral head develop within the acetabulum more naturally. The design also promotes compliance by allowing a degree of comfort and mobility, making it more tolerable for children to wear over an extended period.

Planning and construction

The torso and thigh support (Figure 3) are made from rigid materials, such as polypropylene or thermoplastic, which provide stabilization. The inner padding is typically made of Ethaflex to prevent skin irritation and ensure comfort. The measure and casting of the torso and thighs to fabricate the proper-sized support.

The device features bi-axial hip joints that allow for controlled motion in both the frontal and sagittal planes, as well as flexion and controlled abduction. The hinges should be designed with stainless steel to ensure durability and ease of movement. The hinge joints should be carefully aligned to allow abduction/adduction and flexion/extension. Polypropylene sheet, Ethaflex, a hinge joint, and stainless steel were used in the fabrication process.

Fabrication process

For this purpose, a mold of the patient’s torso is created through casting, and precise measurements are used to design the customized support. After casting, the negative cast is poured to form a positive modified mold. Then, the mold is biomechanically modified, and the thermoplastic material is heated and vacuum-formed over the mold to form the rigid base. The edges are trimmed and smoothed to avoid discomfort or irritation.

Similar to the torso support, the thigh cuffs are molded and formed using thermoplastic or polypropylene. Then, foam padding is added for comfort, and the edges are smoothed.

A size-1 single-axis hip joint is taken for frontal and sagittal plane motions, and a small hinge joint is welded at the proximal end of the joint uprights. As a result, it acts as a bi-axial joint for the hip, allowing for flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. Then, the hinges are correctly aligned over the torso support, with respect to the anatomical hip joint, to allow smooth, controlled movements without impinging.

Next, the lower upright of the hip joint is attached to the thigh shell. The upright is bent with a proper abduction angle. After fabrication, the orthosis should be fitted to the patient, ensuring that all moving parts operate smoothly. Adjustable straps are attached using rivets to secure the orthosis onto the torso. Additionally, the straps and joint alignments are adjusted as needed for optimal comfort and function.

Biomechanics of the orthosis

The principle of the concurrent force system underlies the biomechanics of a hip abduction orthosis designed for DDH. The concept is that the force exerted by the orthosis will collaborate with the anatomical forces at play on the hip joint to reach a desired result. In this force system, the lines of action of all forces intersect at a single point [8]. A concurrent force system, in this context, refers to the situation where several forces are simultaneously acting on the hip joint and collaborating to establish stability.

The principle underlying this system (Figure 4) is the biomechanics of a hip abduction orthosis designed for DDH. The concept is that the force exerted by the orthosis will collaborate with the anatomical forces at play on the hip joint to reach a desired result. In this system, the lines of action of all forces intersect at a single point [8]. A concurrent force system, in this context, refers to the situation where several forces are simultaneously acting on the hip joint and collaborating to establish stability. The hip abduction orthosis provides an external force that aligns with anatomical forces (e.g. the muscle and ligament forces around the hip joint) to keep the femoral head securely within the acetabulum (the hip socket).

The hip joint is a bi-axial joint, allowing motion in two primary planes of motion. To stabilize it in abduction, the orthosis applies forces in the vertical and horizontal directions.

Basically, two concurrent force couples act just above and below the hip joint. The bi-axial hip joint is concurrent with the lateral force. Thereby, the vertical component (Sin θ components) of relaxation is multiplied by the opposite force (Equation 1). Thus:

1. F Sin θ1-F Sin θ2=0

However, the horizontal component is aggregated as 2 Cos(θ1 θ2); as a result, it causes snug-fitting capsulation within the cavity (Equation 2). Hence:

2. F=F Cos θ1+F Cos θ2

Now, there is another force couple, applied by the orthosis, that is, θ1 Sin θ1 & θ1 Cos θ1.

Again, the vertical component gets canceled out by the total weight (W); as a result, the horizontal component is responsible for the encapsulation of the hip joint (Equation 3). Accordingly:

3. Total force=F1 Cos θ1+F2 Cos θ2+F3 Cos θ3

F1 Sin θ1=W

Mechanism of the modified device

The modified device operates through a bi-axial mechanical hip joint that facilitates femoral abduction, allowing for a more natural range of motion in the hip (Figure 5). Enhanced containment is achieved by the relative abduction of the femur, which works in tandem with the moment of inertia to stabilize the limb. Vertical traction, exerted by the torso, provides additional support and aids in controlled rotation, thereby optimizing the stability of the device during use. Furthermore, the mechanical hip joint allows for necessary flexion and a limited degree of extension, thereby enabling active ambulation while maintaining stability and support.

Evaluation of the force system

Evaluating the force system involves assessing three primary forces. The abduction force pushes the femur outward while pulling the femoral head upward against the socket, thereby promoting proper alignment. The containment force, applied by straps or a pad, generates a gentle inward force to secure the limb in place. Finally, the countertraction force, exerted by the torso, creates an upward pull that balances the downward pressure, contributing to overall stability and support within the socket.

Impact of the orthosis

The capitular sulcus is more developed, with proper reduction of avulsion. This controlled dysplasia reduces stress on the spine, thus minimizing the risk of developing excessive lordosis, kyphosis, or scoliosis (Figures 6 and 7). A well-executed reduction of avulsion can significantly impact spinal health by managing controlled dysplasia. This control minimizes undue stress on the spine, effectively reducing the risk of other conditions (e.g. lordosis or kyphosis) and lowering the likelihood of scoliosis development.

The following measurements (steps 1–14) and two ratios were utilized, with measurements in mm and angles in degrees (Figure 8). Initially, a vertical line representing the midline (M) is drawn through the sacrum and the symphysis pubis. Subsequently, the Hilgenreiner’s horizontal line (H) is drawn through the triradiate cartilage at the lowest point of the ilium. In addition, the Perkins’ line (P) is established at a right angle to the H-line at the edge of the bony acetabulum. Then the following lines were drawn:

The distance from the midpoint of the ossification center of the femoral head to the midline (X1), the distance from the center of the ossific nucleus of the femoral head to the P-line (X2) measured at a negative value when it is lateral to the P-line, the distance from the center of the ossific nucleus of the femoral head to the H-line (indicated as a negative value when it is above the H-line) (Y), The width of the acetabular edge and the ossific nucleus of the femoral head (D1), the height of the femoral head ossific nucleus (D2), the distance from the most medial proximal femoral metaphysis to the midline (c), the distance from the most superior point of the proximal femoral metaphysis to the H-line (a negative value if above the H-line) (h), abstand modified head-tear (HT) drop, abstands von der P-Linie zur Mittellinie (b), A1: Acetabular length, and A2: Acetabular depth.

The acetabular angle (in degrees) is the angle between the H-line and the line that connects the lowest point of the ilium to the acetabular edge.

The ratio is calculated by measuring the distance from the most medial femoral metaphysis to the midline and from the P-line to the midline (known as Smith’s c/b ratio for lateral or horizontal displacement).

Another ratio is determined by measuring the distance from the most superior femoral metaphysis to the H-line and from the P-line to the midline (known as Smith’s h/b ratio for superior or vertical migration).

Results

The results demonstrated an improvement in joint alignment and enhanced stabilization of the hip joint, contributing to decreased laxity in the capsule and ligament (Table 1).

These effects could promote healthy cartilage development and facilitate the formation of the capitular sulcus. Moreover, the intervention had a preventative role against complications such as kyphosis, leg length discrepancy, and osteoarthritis. Overall, these outcomes supported improved quality of life and functional performance in the individuals involved.

Discussion

It is important to be careful about treating DDH since a risk of nutritional problems in the hip joint accompanying it. Using orthotic treatment is best for kids under 6 months old, as it can interfere with hip growth later on. If parents do not cooperate, it can lead to complications or reduce the effectiveness of the treatment [21]. Doctors believe that bracing is the best way to treat DDH in babies under 6 months old with hips that can be fixed. The baby’s hip with DDH needs to stay in a safe position with 100° flexion and abduction that is not more than 60°. A review of bracing revealed that dynamic bracing is typically worn full-time for approximately 16.4 weeks, while static bracing is worn for around 8.9 weeks [22, 23]. Reductions were achieved in this case. The new design gradually fixes the problem over time until it is fully resolved. This finding indicates that the patient is satisfied with the orthosis. A rigid brace helps keep the hips in a straighter position than a standard Pavlik harness and can prevent dislocations by securely holding the hip in place [24, 25].

The brace was created to help doctors, parents, and children deal with DDH more easily in their daily lives. It is made of lightweight, flexible material, making it simple for parents to use every day. Additionally, our brace lets babies sit comfortably. Furthermore, adjusting the brace during treatment is easily accomplished by gently heating and shaping the thermoplastic material into the right position. The goal of using splints is to fix the hip’s position and promote proper joint development.

Köse et al. evaluated the effectiveness of abduction orthosis in treating primary AD [26]. They found that its use led to significant improvements in AI values, suggesting that early intervention is crucial for patients with primary AD. It is worth noting that dysplastic hips improved more in AI than non-dysplastic hips within the first 6 months of therapy. This outcome aligns with the quicker improvement observed in our study during the initial treatment phase.

Specialists debate the best time for treatment between 6 months old and 18 months old. The Pavlik harness is less effective after 6 months, so doctors suggest pelvic osteotomy after 18 months old. Waiting for the hip socket to develop on its own as the child grows older is impractical since delaying treatment can lead to more severe cases of hip dysplasia. Spontaneous resolution is unlikely [27]. Although the Pavlik harness is a reliable method for treating DDH, its effectiveness may decline in babies over six months old, particularly those over four months old. When the Pavlik harness does not give acceptable results in older and more active children, doctors often use an abduction orthosis instead. There is limited information available on the use of abduction orthoses to treat AD. Gans et al evaluated babies with stable DDH who had been treated but still had AD at 6 months old. They observed that using bracing when the 6-month x-ray shows an AI greater than 30 degrees helps improve the AI between 6 months and 12 months of age more effectively than just watching or using the Pavlik harness [28].

Radiological parameters have proven to be invaluable in the diagnosis and management of DDH. Several measurements have been employed to aid in the radiographic evaluation of DDH. The findings of this research corroborate the potential usefulness of different radiographic measurements in determining treatment methods for DDH cases in children aged 12–24 months [29].

According to the most recent studies, employing specific radiographic measurements in cases of DDH may aid in decision-making regarding whether conservative or surgical treatment is warranted. The ossific nucleus of the femoral head (D1) was found to have a greater width in cases of conservative treatment, indicating that a larger nucleus size at the first evaluation correlates with higher success rates for conservative treatment among individuals of the same age group. This study identified measurements from pre-reduction radiographs as the best indicators for the need for operative treatment after CR: femoral head lateralization (X1, c, HT, and c/b ratio), superior migration of the femoral head (Y, h, and h/b ratio), and an acetabular angle (T).

Conclusion

In general, the x-ray results indicated that the avulsion reduction achieved with this intervention closely approaches normal alignment, promoting proper encapsulation. This newly designed, modified articulated orthosis not only corrects the deformity effectively but also allows for the restoration of normal functional movement. Yet, using an abduction orthosis is a safe and effective way to possibly lower the chances of suffering from osteoarthritis at a young age and avoid the need for surgery later on. Further research is needed to determine the duration for which the orthosis remains effective and should be worn.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics at Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, India (Code: 10211).

Funding

This paper has been derived from a research project supported by and conducted at Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, India.

Authors' contributions

Methodology and conceptualization: Sushree Sangita Nayak, Srikanta Maharana, and Debashis Behera; Investigation and data curation: Sushree Sangita Nayak and Debashis Behera; Validation and formal analysis: Sushree Sangita Nayak and Srikanta Maharana; Project administration: Srikanta Maharana; Supervision and resources: Debashis Behera and Srikanta Maharana; Visualization and writing the original draft: Sushree Sangita Nayak; Review, and editing: Srikanta Maharana and Debashis Behera.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for her timely cooperation and sincere participation in this study.

References

- Godward S, Dezateux C. Surgery for congenital dislocation of the hip in the UK as a measure of outcome of screening. MRC Working Party on Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. Medical Research Council. Lancet. 1998; 351(9110):1149-52. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10466-4] [PMID]

- Guille JT, Pizzutillo PD, MacEwen GD. Development dysplasia of the hip from birth to six months. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000; 8(4):232-42. [DOI:10.5435/00124635-200007000-00004] [PMID]

- Cooperman DR, Wallensten R, Stulberg SD. Acetabular dysplasia in the adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983; 175:79-85. [DOI:10.1097/00003086-198305000-00013]

- Stulberg SD, Cordell LD, Harris WH, Ramsey PL, MacEwen GD, Wedge JH, et al. Acetabular dysplasia and development of osteoarthritis of the hip. In: Harris WH, editor. The hip: proceedings of the second open scientific meeting of the Hip Society. St. Louis: Mosby; 1974. [Link]

- Jones GT, Schoenecker PL, Dias LS. Developmental hip dysplasia potentiated by inappropriate use of the Pavlik harness. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992; 12(6):722-6. [DOI:10.1097/01241398-199211000-00004] [PMID]

- Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital disease of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979; 61-B(3):334-8. [DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.61B3.158025] [PMID]

- Escribano García C, Bachiller Carnicero L, Marín Urueña SI, Del Mar Montejo Vicente M, Izquierdo Caballero R, Morales Luengo F, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Beyond the screening. Physical exam is our pending subject. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2021; 95(4):240-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.anpede.2020.07.024] [PMID]

- Alhaddad A, Gronfula AG, Alsharif TH, Khawjah AA, Alali MY, Jawad KM. An overview of developmental dysplasia of the hip and its management timing and approaches. Cureus. 2023; 15(9):e45503. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.45503]

- Kolb A, Chiari C, Schreiner M, Heisinger S, Willegger M, Rettl G, et al. Development of an electronic navigation system for elimination of examiner-dependent factors in the ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1):16407. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-73536-9] [PMID]

- Thaler M, Biedermann R, Lair J, Krismer M, Landauer F. Cost-effectiveness of universal ultrasound screening compared with clinical examination alone in the diagnosis and treatment of neonatal hip dysplasia in Austria. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011; 93(8):1126-30.[DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.25935] [PMID]

- Dwan K, Kirkham J, Paton RW, Morley E, Newton AW, Perry DC. Splinting for the non-operative management of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in children under six months of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022; 10(10):CD012717.[DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD012717.pub2] [PMID]

- Hassebrock JD, Wyles CC, Hevesi M, Maradit-Kremers H, Christensen AL, Levey BA, et al. Costs of open, arthroscopic and combined surgery for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2020; 7(3):570-4. [DOI:10.1093/jhps/hnaa048] [PMID]

- Schwanitz von Keitz P, Kleimeier D, Lutter CF, Rehberg M, Mittelmeier W, Kasch R, et al. The effect of the design of the orthosis on the axial load transmission of two flexion abduction orthoses used in treating congenital hip dysplasia. Heliyon. 2022; 8(12):e11942. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11942] [PMID]

- Mittelmeier H, Deimel D, Beger B. [An ultrasound hip screening program--middle term results of flexion-abduction orthosis therapy (German)]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1998; 136(6):513-8. [DOI:10.1055/s-2008-1045179] [PMID]

- Multerer C, Döderlein L. [Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip: proven and new procedures in diagnostics and therapy (German)]. Orthopade. 2014; 43(8):733-41. [DOI:10.1007/s00132-013-2225-7] [PMID]

- Pavlik A. Stirrups as an aid in the treatment of congenital dysplasias of the hip in children. By Arnold Pavlik, 1950. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989; 9(2):157-9. [DOI:10.1097/01241398-198903000-00007] [PMID]

- Klein P, Sommerfeld P. [Biomechanics of human joints: Fundamentals, Pelvis, Lower Extremity (German)]. München: Urban & Fischer; 2004. [Link]

- Iwasaki K. Treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip by the Pavlik harness. Mechanism of reduction and usage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983; 65(6):760-7. [PMID]

- Song KM, Lapinsky A. Determination of hip position in the Pavlik harness. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000; 20(3):317-9. [DOI:10.1097/01241398-200005000-00009]

- Atalar H, Sayli U, Yavuz OY, Uraş I, Dogruel H. Indicators of successful use of the Pavlik harness in infants with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop. 2007; 31(2):145-50. [DOI:10.1007/s00264-006-0097-8] [PMID]

- Kocoń H, Komor A, Struzik S. Orthotic treatment of developmental hip dysplasia. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2004; 6(6):825-9. [PMID]

- Pavone V, de Cristo C, Vescio A, Lucenti L, Sapienza M, Sessa G, et al. Dynamic and static splinting for treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: A systematic review. Children (Basel). 2021; 8(2):104. [DOI:10.3390/children8020104] [PMID]

- Merchant R, Singh A, Dala-Ali B, Sanghrajka AP, Eastwood DM. Principles of bracing in the early management of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Indian J Orthop. 2021; 55(6):1417-27.[DOI:10.1007/s43465-021-00525-z] [PMID]

- Hedequist D, Kasser J, Emans J. Use of an abduction brace for developmental dysplasia of the hip after failure of Pavlik harness use. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003; 23(2):175-7. [DOI:10.1097/00004694-200303000-00008] [PMID]

- Viere RG, Birch JG, Herring JA, Roach JW, Johnston CE. Use of the Pavlik harness in congenital dislocation of the hip. An analysis of failures of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990; 72(2):238-44. [DOI:10.2106/00004623-199072020-00011] [PMID]

- Köse M, Yılar S, Topal M, Tuncer K, Aydın A, Zencirli K. Simultaneous versus staged surgeries for the treatment of bilateral developmental hip dysplasia in walking age: A comparison of complications and outcomes. Jt Dis Relat Surg. 2021; 32(3):605-10. [DOI:10.52312/jdrs.2021.38] [PMID]

- Vitale MG, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip from six months to four years of age. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001; 9(6):401-11. [DOI:10.5435/00124635-200111000-00005] [PMID]

- Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013; 33(7):714-8. [DOI:10.1097/BPO.0b013e31829d5704] [PMID]

- Boniforti FG, Fujii G, Angliss RD, Benson MK. The reliability of measurements of pelvic radiographs in infants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997; 79(4):570-5. [DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.79B4.7238] [PMID]

Type of Study: Case Study |

Subject:

Prosthetics and Orthotics

Received: 2025/03/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/25 | Published: 2025/05/10

Received: 2025/03/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/25 | Published: 2025/05/10