Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Praditasari T A, Isbayuputra M, Friska D, Bashiruddin Herqutanto J, Prawiroharjo P. Music-induced Tinnitus and Sleep Quality: A Study Among Regular Professional Musicians in Indonesia. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-297-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-297-en.html

Tasya Aulia Praditasari *1

, Marsen Isbayuputra2

, Marsen Isbayuputra2

, Dewi Friska2

, Dewi Friska2

, Jenny Bashiruddin Herqutanto3

, Jenny Bashiruddin Herqutanto3

, Pukovisa Prawiroharjo4

, Pukovisa Prawiroharjo4

, Marsen Isbayuputra2

, Marsen Isbayuputra2

, Dewi Friska2

, Dewi Friska2

, Jenny Bashiruddin Herqutanto3

, Jenny Bashiruddin Herqutanto3

, Pukovisa Prawiroharjo4

, Pukovisa Prawiroharjo4

1- Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia. , tasya.aulia11@ui.ac.id

2- Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

3- Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

4- Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2- Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

3- Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

4- Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Full-Text [PDF 561 kb]

(197 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1014 Views)

Full-Text: (44 Views)

Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external sound source, often in the form of a buzzing, hissing, or ringing sensation in the ears. This condition can be temporary or permanent and is often caused by a disturbance of the hearing system due to noise exposure, as in the case of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Tinnitus affects physiological aspects and significantly impacts the quality of life (QoL), including sleep disturbances, emotional distress, and cognitive difficulties. The exact mechanisms are still not fully understood, but changes in the neural networks that process sound perception are involved. Objective measurement approaches, such as cortical auditory potentials and evaluation of the pre-pulse inhibition response (gap pre-pulse inhibition of the acoustic startle, [GPIAS]), have been introduced to further understand the characteristics of tinnitus, especially to noise exposure and its effects on the sufferers’ QoL.

Noise exposure is one of the most common workplace hazards. A 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) report showed that as many as 1.1 billion people aged 12-35 are at risk of hearing loss due to noise exposure [1]. One of the hearing system disorders due to excessive exposure to loud noise is NIHL [2], and one of the early symptoms of NIHL hearing loss is tinnitus [3]. Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external source, which can be permanent or temporary and is significantly associated with poor QoL, absence from work, and sleep disturbances [4]. Research has shown a relationship between tinnitus and the onset of sleep disturbances. Patients with tinnitus tend to have high Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) scores, and decreased sleep quality correlates with self-reported tinnitus [5].

Occupational noise exposure is the biggest risk factor associated with tinnitus and hearing loss among music industry workers [6]. Musicians perform and practice music regularly and are exposed to high-intensity sounds throughout the day [7]. This puts them at a high risk of developing tinnitus, which can majorly impact their personal and professional lives. Although musicians are at risk of hearing loss and tinnitus, research shows that they are less concerned about these issues [8]. If the symptoms of hearing loss can be detected early, it can favor musicians, maintaining their ability to perform well [9]. However, the literature on tinnitus and sleep quality in musicians is limited. This study aims to investigate the relationship between tinnitus due to music exposure in the workplace and sleep quality, risk factors associated with tinnitus occurrence, and factors associated with the sleep quality of regular professional musicians in Jakarta.

Materials and Methods

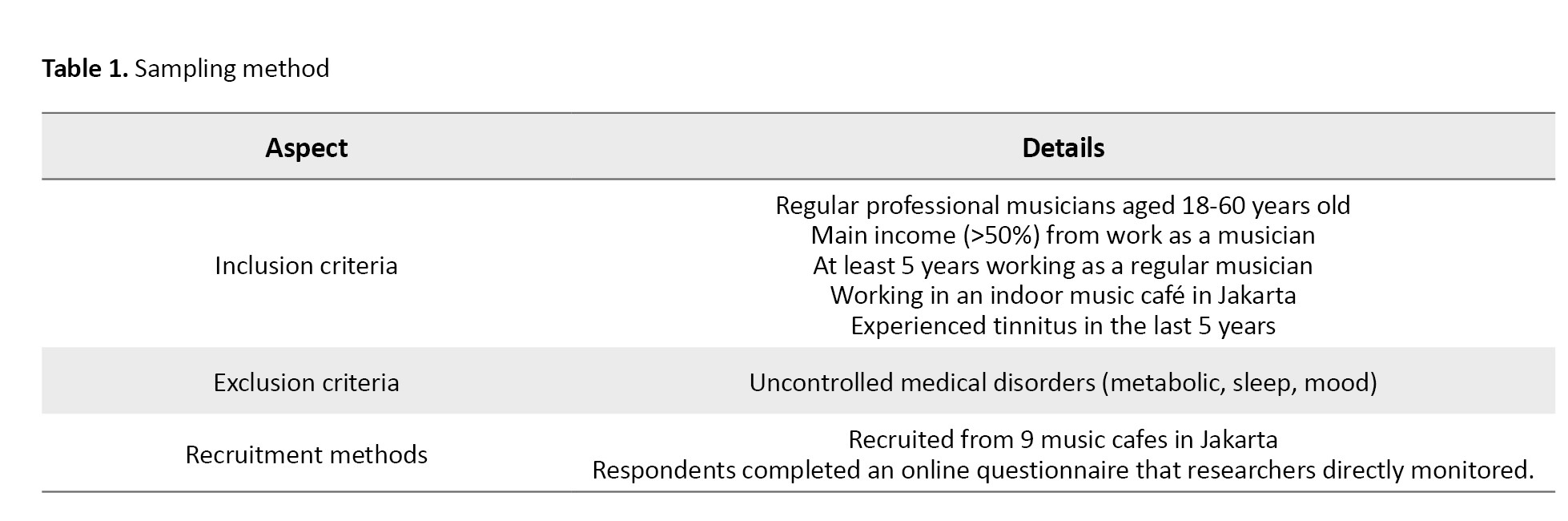

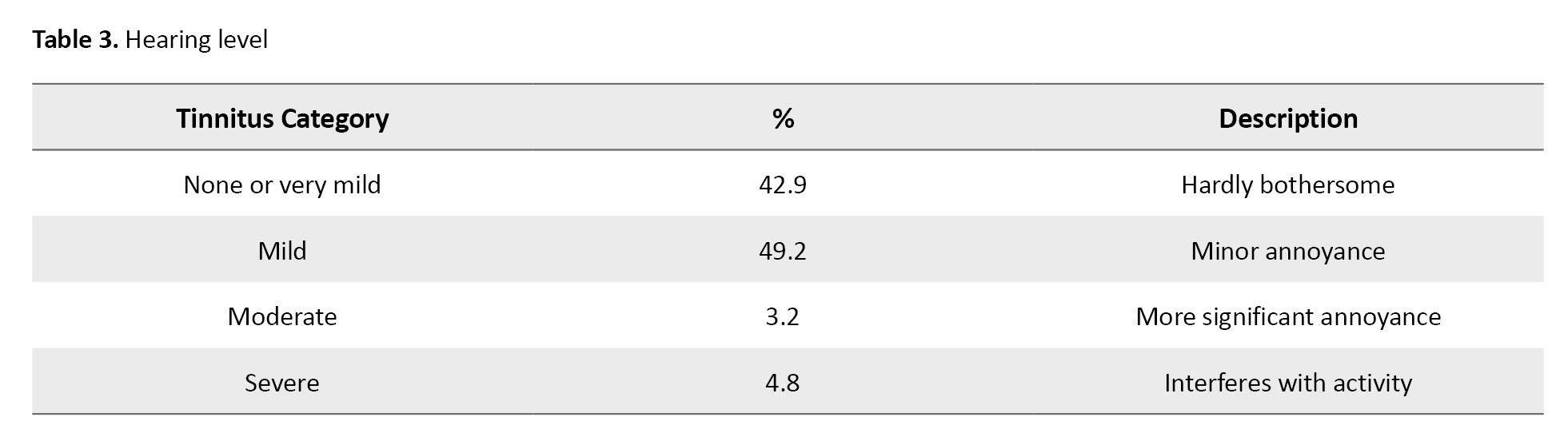

This cross-sectional study aimed to determine the relationship between tinnitus due to music exposure in the workplace and sleep quality in musicians. The study was conducted in July 2023 at nine cafes in Jakarta. The study population comprised regular professional musicians in Jakarta who performed music indoors. The inclusion criteria included regular professional musicians aged 18-60 years with the main income (>50% of income) obtained from working as a musician, performed music concerts for at least 2 hours in a week, worked as a regular professional musician for ≥5 years, worked in an indoor venue in Jakarta that performed live music using a sound system speaker, experienced tinnitus within 5 years before collecting research data and provided written consent. The exclusion criteria included uncontrolled medical conditions that interfere with metabolism, sleep, or mood function, history of recurrent otitis media, previous head trauma, infection of the central nervous system, ear, nose, and throat system diseases related to airway obstruction, ear surgery, consumption of ototoxic drugs, and body mass index >35 kg/m2 (severe obesity). The degree of tinnitus was assessed using the tinnitus handicap index (THI) questionnaire, and sleep quality was assessed using the validated PSQI questionnaire, both in the validated Indonesian version. We also conducted otoacoustic. However, Otoacoustic emission (OAE) cannot be performed on all samples because of the lack of a quiet room. Noise measurements were analyzed using a calibrated sound level meter with the Occupational Health Center Hiperkes Jakarta team. The questionnaire was filled out online through Google Forms, which was monitored directly by the researcher. Working hours per day were defined as the number of hours the musician worked per day. Meanwhile practice hours in a week were defined as the number of musician practice hours accumulated in a week; both data were obtained from interviews with the subjects. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25, with a significance level of P<0.05.

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design to investigate the relationship between tinnitus due to workplace music exposure and sleep quality among musicians. Data were collected in July 2023 from nine cafes in Jakarta. The study population included regular professional musicians performing indoor music in Jakarta.

Sampling and data collection

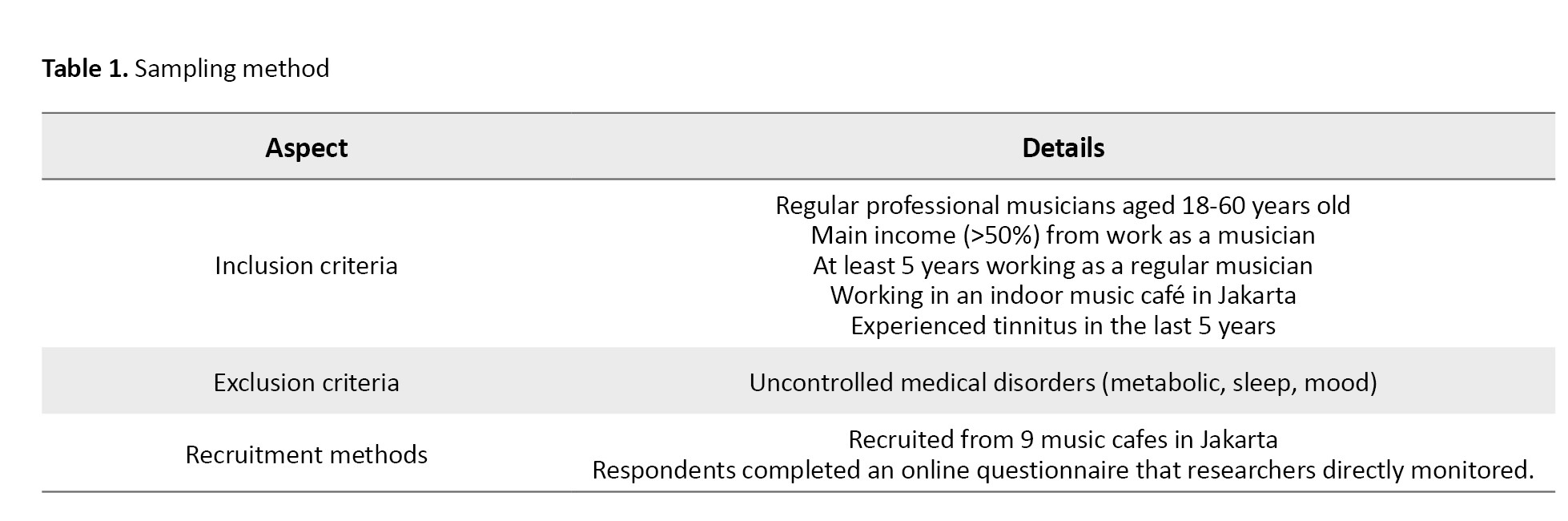

Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method targeting eligible musicians in selected cafes. Eligible participants were contacted and assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The participants were divided into two groups: Those with tinnitus (cases) and those without tinnitus (controls). Sleep quality was compared between the two groups to allow for a descriptive-analytic cross-sectional analysis. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and the recruitment procedure are summarized in Table 1.

Data analysis

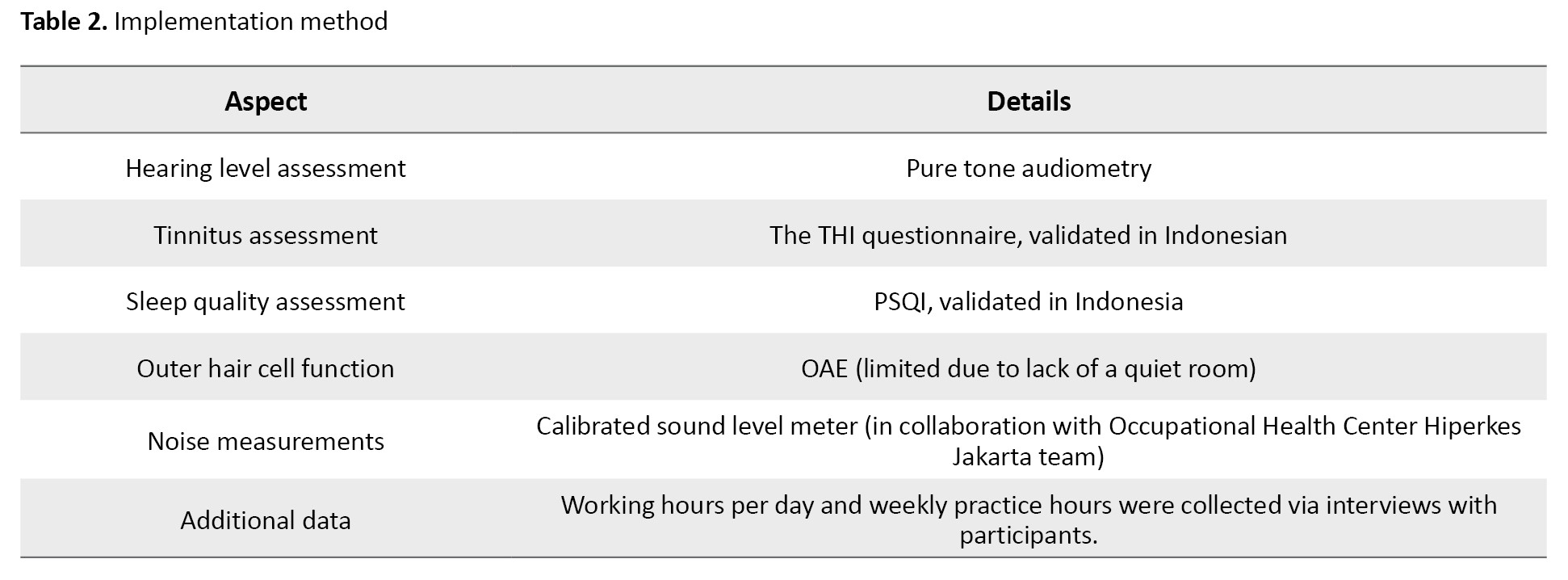

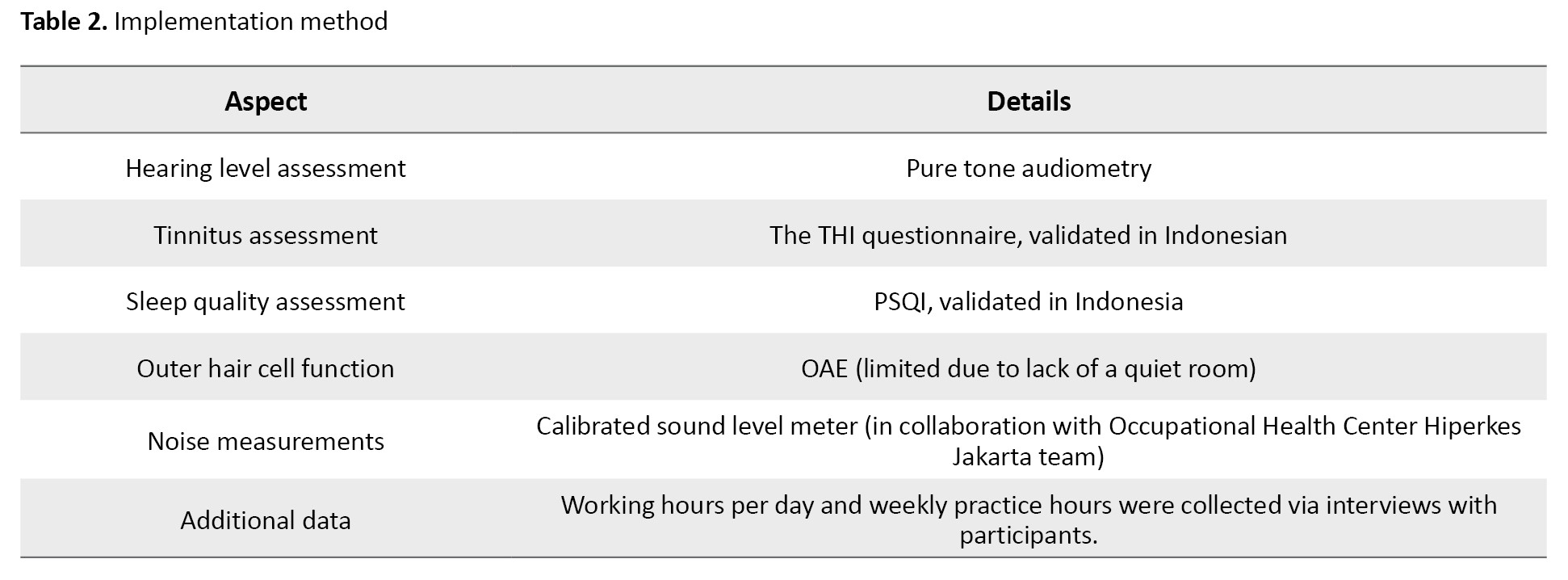

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25, with statistical significance at P<0.05. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics, while inferential statistics (e.g. t-tests or chi-square tests) were applied to compare sleep quality between groups. The instruments and measurement procedures used in this study, including THI, PSQI, pure tone audiometry, OAE, and noise measurements, are detailed in Table 2.

Results

This study included 63 musicians who met the inclusion criteria and completed the THI and PSQI questionnaires as well as noise-exposure assessments.

Tinnitus severity distribution

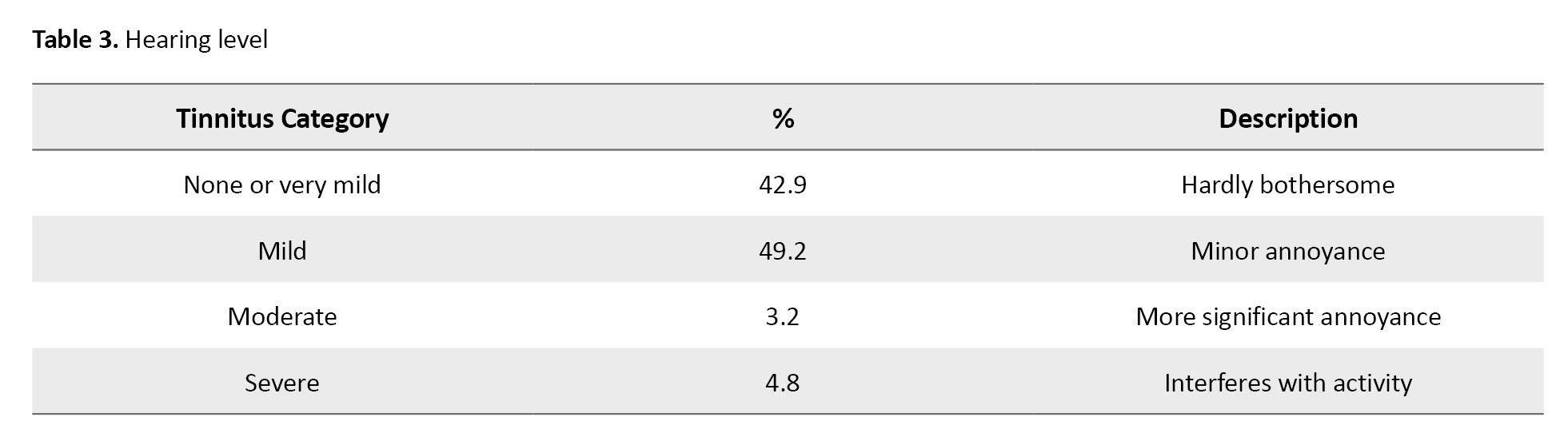

Table 3 presents the distribution of tinnitus handicap categories according to the THI score.

In this sample, 49.2% of the musicians worked as musicians for 5–10 years. Most musicians reported exposure to loud music during work, with the median noise level experienced being 99.8 dB. A total of 49.2% of musicians reported mild tinnitus, while 29.4% experienced moderate tinnitus, and one respondent (1.6%) reported severe tinnitus. The median THI score was 18, categorized as mild.

Respondent characteristics

Table 4 presents the distribution of respondents’ demographic and occupational characteristics.

The median number of working days per week was five, while the median practice hours per week was six. Most musicians never use ear-protection equipment, although 54% reported using in-ear monitors during work. According to the PSQI, 73% of musicians had poor sleep quality with a median total score of 8.

Bivariate analysis between tinnitus and sleep quality

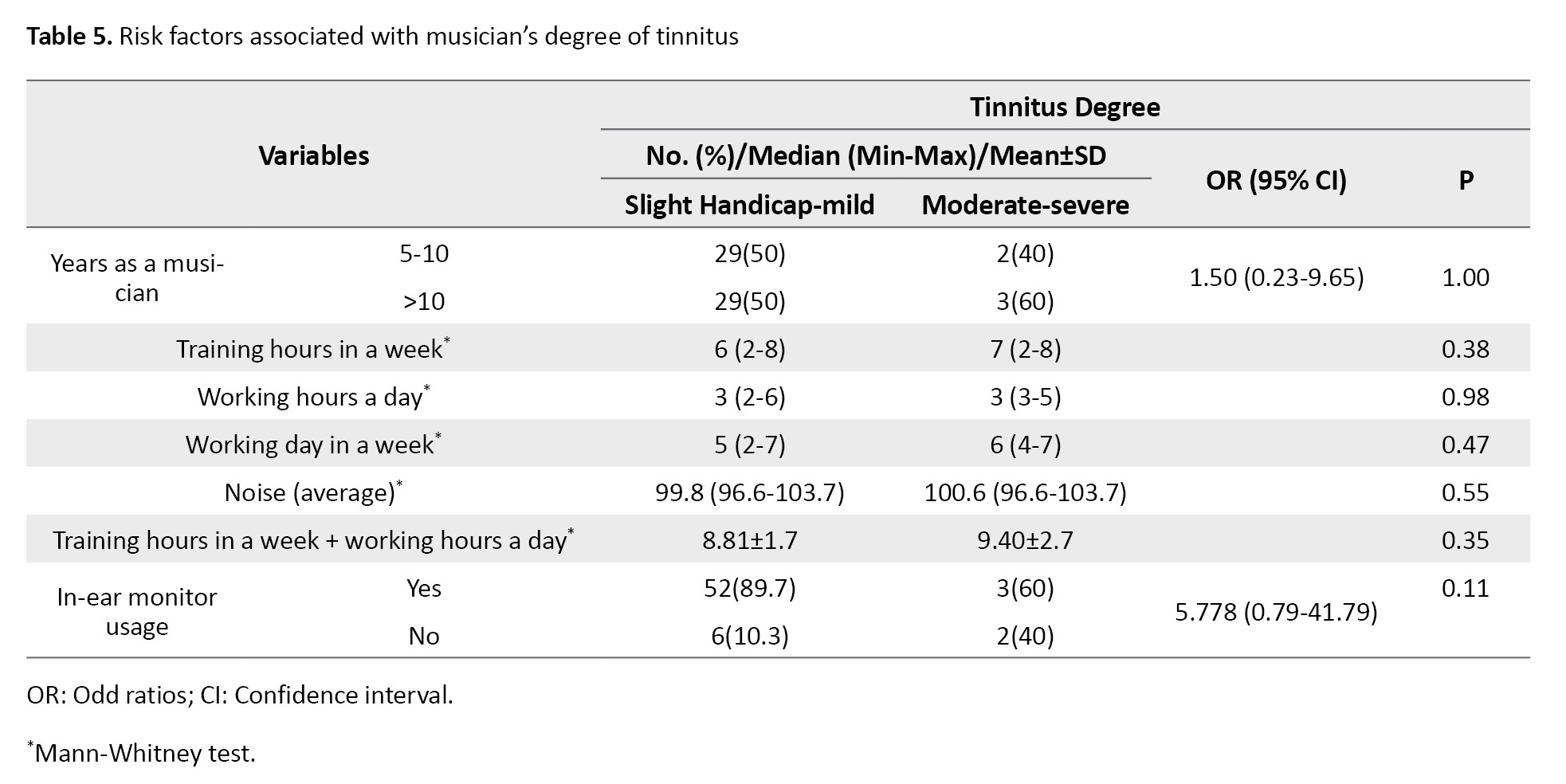

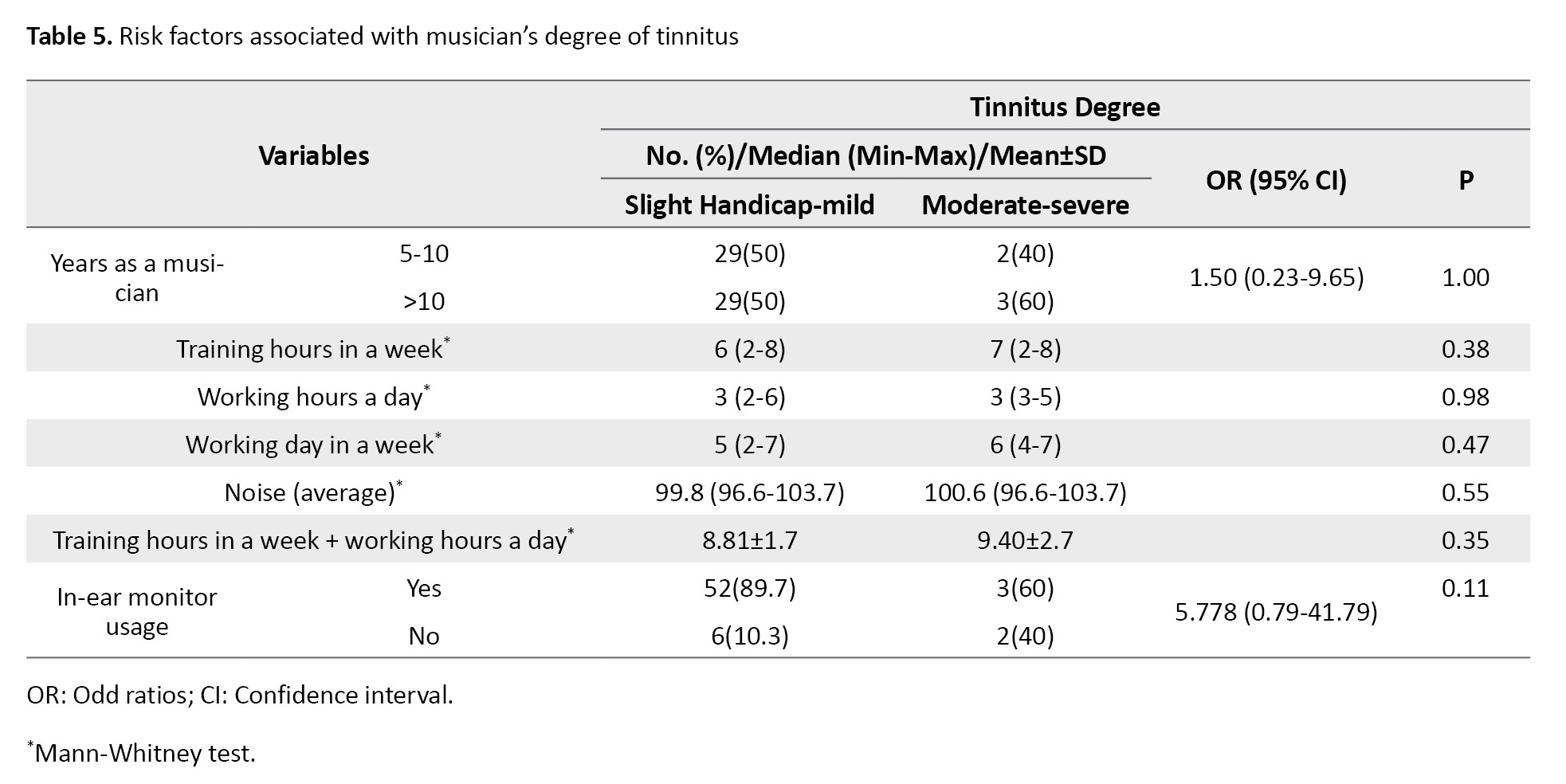

Table 5 shows the bivariate analysis of the relationship between tinnitus severity and musicians’ sleep quality.

There was no significant association between tinnitus severity and sleep quality (P=1.00). However, several occupational factors demonstrated significant relationships with sleep quality. These included years working as a musician, practice hours per week (P=0.02), working hours per day (P=0.03), and the average noise exposure level.

Risk factors associated with musicians’ sleep quality

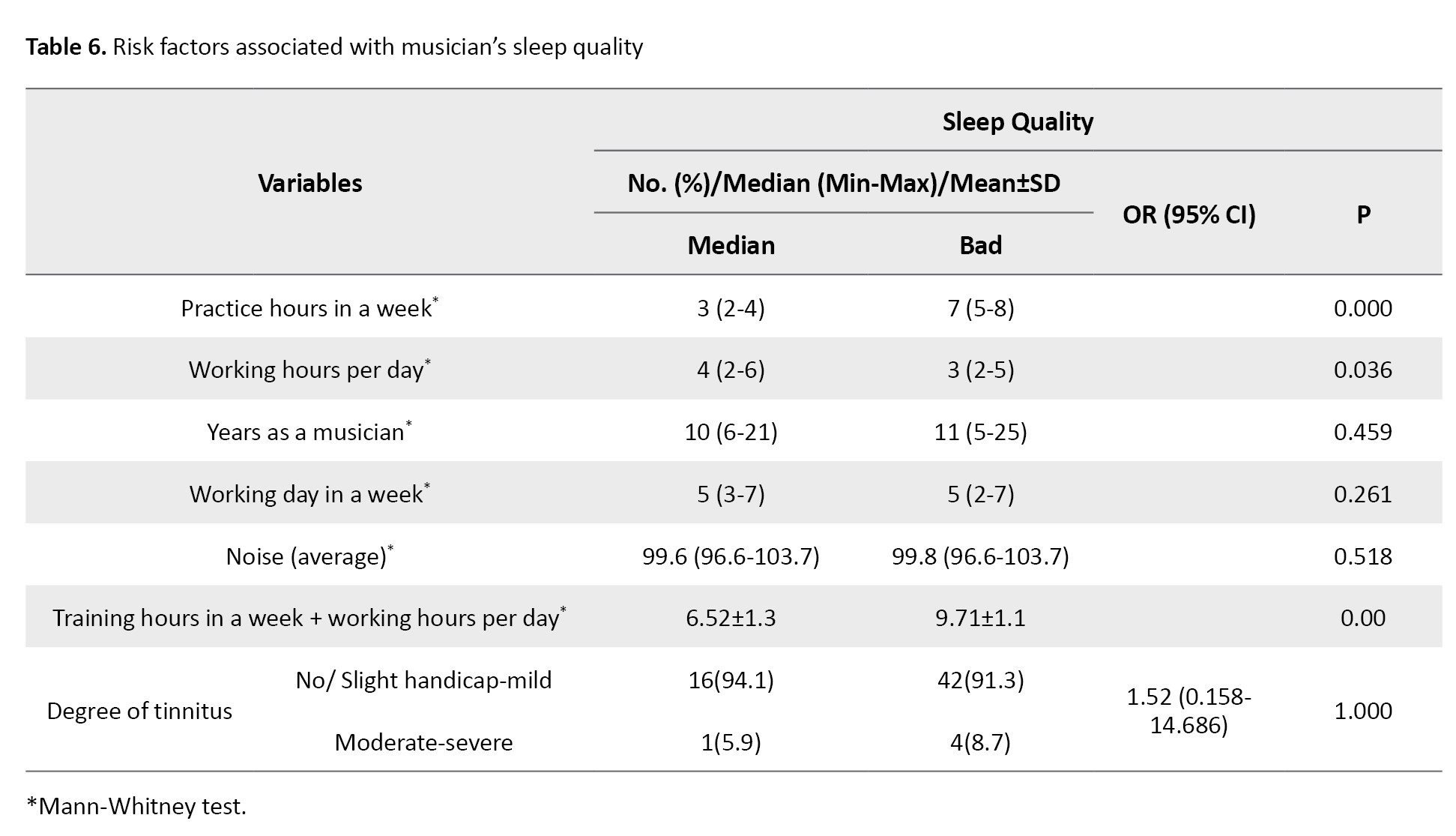

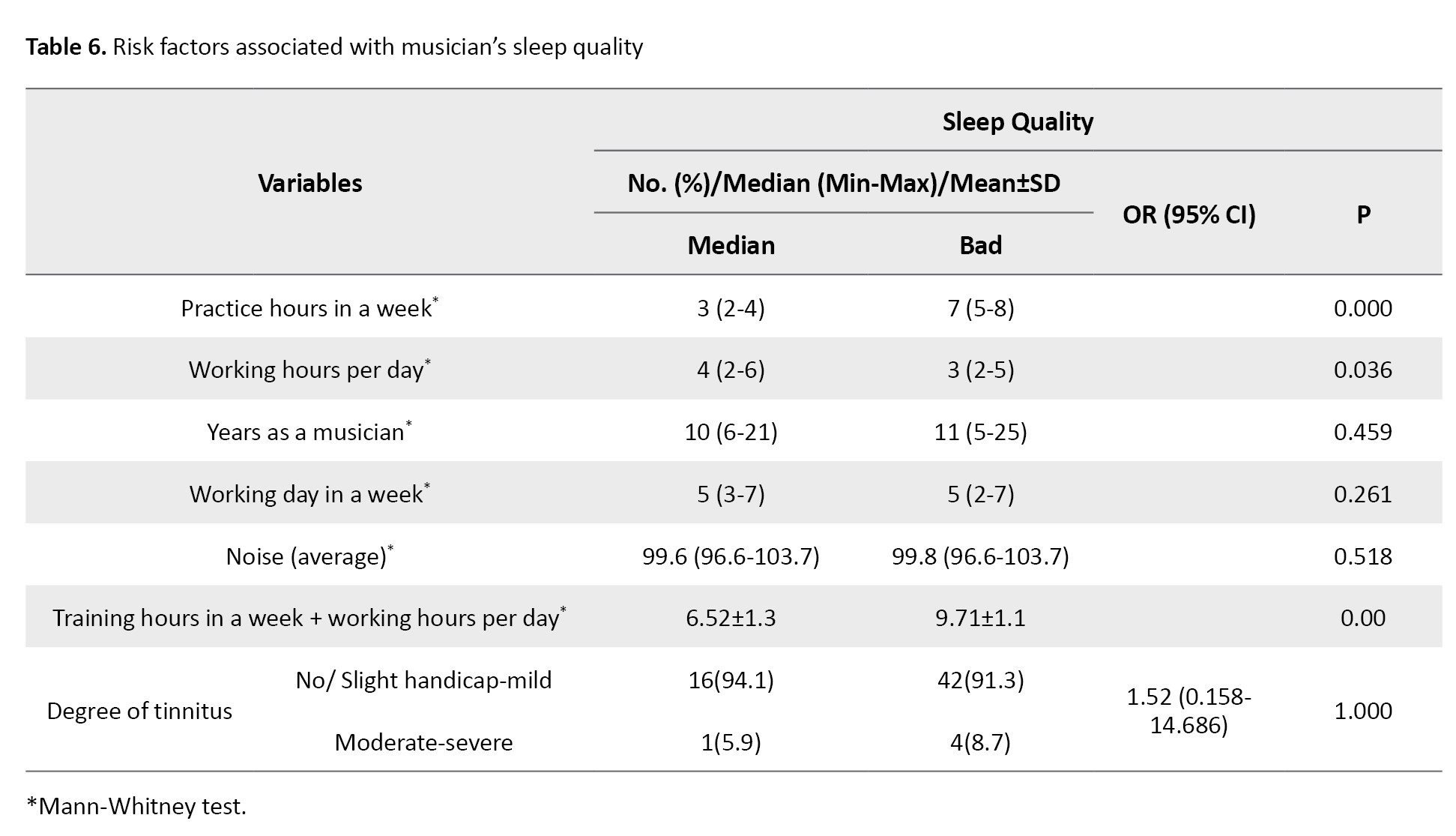

Table 6 summarizes the risk factors associated with sleep disturbance among musicians.

Upon bivariate analysis, musicians with more practice hours per week and longer working hours per day were significantly more likely to experience poor sleep quality. Additionally, merged variables of sleep quality showed significant associations with musicians’ training hours per week and working hours per day (P=0.00).

Binary logistic regression analysis

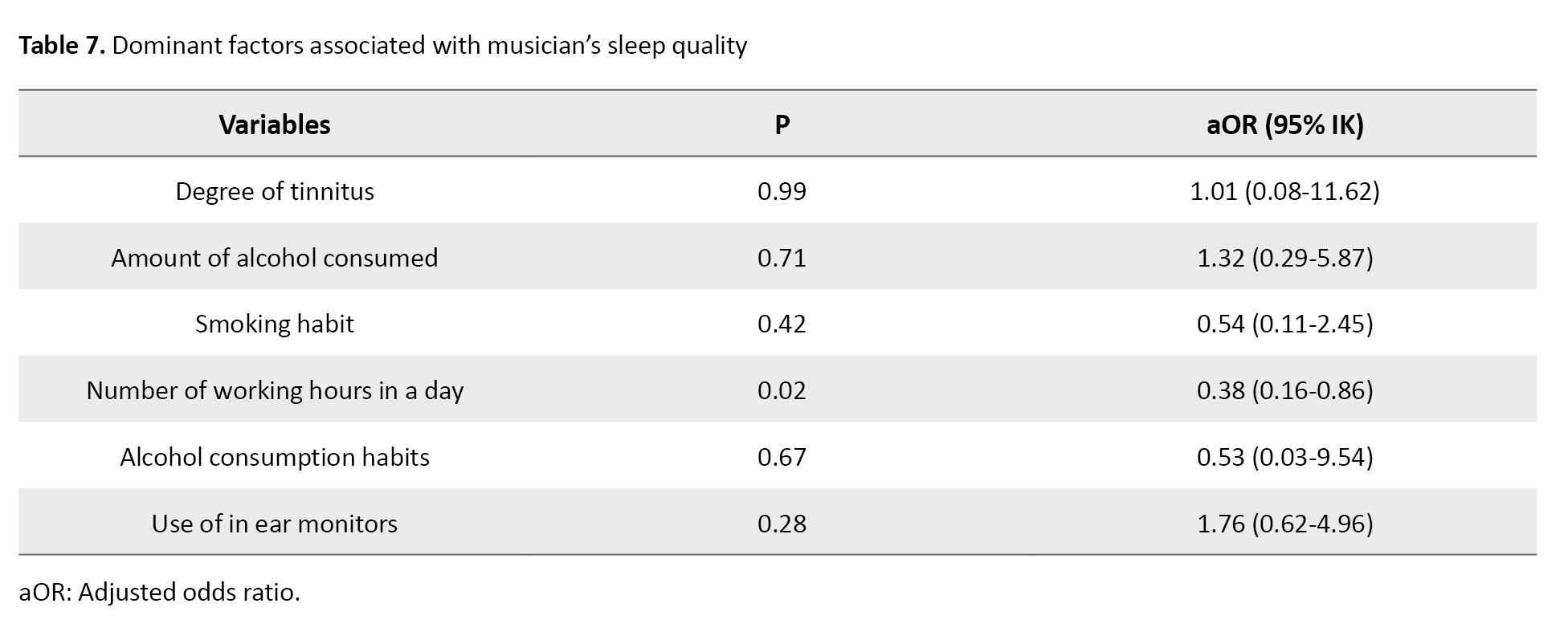

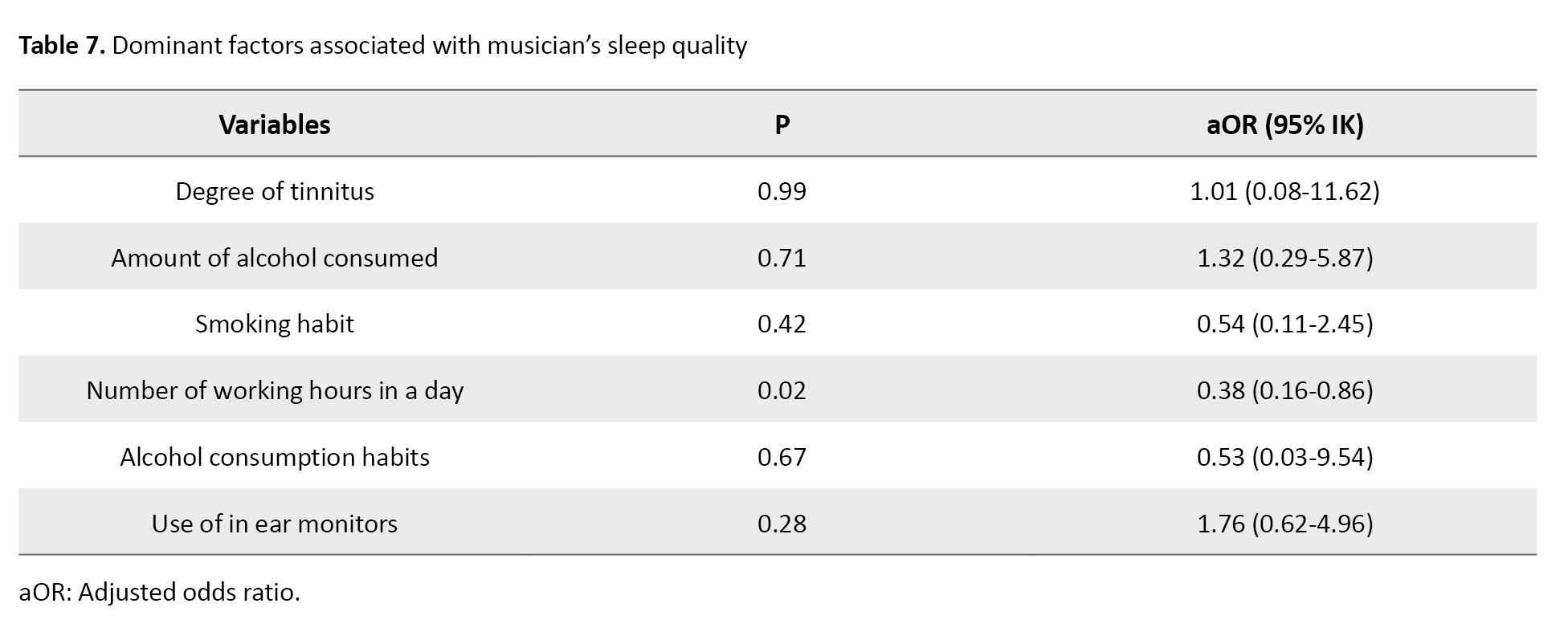

Table 7 presents the binary logistic regression analysis outcomes.

The factor that independently influenced sleep quality was the number of working hours per day, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.38 (95% CI, 0.16%, 0.86%). Musicians who worked longer hours were 62% less likely to have good sleep quality. The two significant variables that remained in the multivariable model—sleep quality disturbance and working hours—explained 25.9% of sleep disturbance variance (pseudo R²=0.25).

Tinnitus severity and sleep-quality distribution

Table 8 displays tinnitus levels among musicians with varying sleep-quality outcomes.

Although 72.4% of musicians with mild tinnitus and 80% of those with moderate tinnitus reported poor sleep quality, this difference was not statistically significant (P>0.05). This finding supports the interpretation that sleep disturbance in this population is more strongly influenced by work-related factors than by tinnitus severity.

Discussion

In this study, 49.2% of the respondents had worked as musicians for 5-10 years. The median of the average noise experienced by musicians while working was 99.8 dB, which exceeds the recommended threshold value of 85 dB. Most musicians experienced mild tinnitus (49.2%), and none experienced severe tinnitus [10]. The median THI score was 18, which was categorized as mild. The PSQI questionnaire showed that 73% of musicians had poor sleep quality, with a median score of 8. This study conducted a 12-frequency OAE examination on eight musicians to assess potential damage to the cochlea's outer hair cells [11]. The examination was limited to eight participants due to the lack of a quiet room, as testing in a non-ideal environment could lead to inaccurate results. This limitation restricts the generalizability of the findings and prevents further analysis of OAE data in the context of this study.

In this study, noise exposure had no significant effect on the degree of tinnitus [12]. The amount of noise exposure was represented by average noise, years as a musician, practice hours per week, working hours per day, and working days per week [8]. Further analysis of the degree of tinnitus was conducted, merging musicians' training hours per week and working hours per day [13]. These variables were not significantly related to the degree of tinnitus. Previous studies in military populations have shown no correlation between tinnitus severity and the amount of noise exposure [14]. One factor that may have affected the results of this study is that most tinnitus cases result from NIHL and are accompanied by changes in the central auditory pathway [15]. This study did not examine the presence or absence of musicians' NIHL; therefore, it is not certain whether the noise exposure was significant enough to cause NIHL, which can cause tinnitus [16].

Compared to ear protection devices, musicians prefer in-ear monitors, with 54% of musicians routinely using in-ear monitors during work. In this study, no significant relationship was observed between using in-ear monitors or ear protection devices and tinnitus severity. Until this study was conducted, no research had discussed the relationship between in-ear monitors and ear protection devices and the degree of tinnitus [17]. Factors that may have interfered with the results include that the volume of the musicians' in-ear monitors was not studied further; therefore, the expected protective effect of the in-ear monitor was not significantly observed.

This study showed no significant relationship between the degree of tinnitus and musicians' sleep quality (P=1.00). No previous research has been related to this. Research on tinnitus and sleep quality in the musician population has only examined the relationship between the presence and absence of tinnitus and sleep quality. Previous research suggests no significant difference in sleep quality between musicians with and without tinnitus [18]. Another study in patients with tinnitus showed a significant relationship between moderate and severe degrees of THI and sleep disturbance [17]. In this study, most musicians had very mild (42.9%) and mild (49.2%) tinnitus; therefore, it was possible that the degree of tinnitus was not enough to disturb musicians' sleep quality, and no significant relationship was observed between the degree of tinnitus and musicians’ sleep quality [19].

A significant relationship was observed between the musicians' training hours per week (P=0.000), working hours per day (P=0.036) and musicians' sleep quality. Musicians had uncertain working hours, and practice was part of the work. Rehearsals would increase musicians working hours; therefore, they would work until late at night. This may affect the musician's sleep cycle, ultimately impacting sleep quality [15]. Years as a musician and working days per week were not significantly related to musicians' sleep quality. The problem of musicians' sleep disorders was sleep dissatisfaction [13] and uncertain working hours; therefore, working days in a week and years as a musician did not significantly impact. A possible mechanism is that the longer the time as a musician, the more accustomed they are to perform; therefore, they do not need as many hours of rehearsal, and the number of working hours in a day would be reduced compared to musicians who were still practicing frequently [12].

This study showed no significant relationship between average noise exposure and musicians' sleep quality. Another study that used the PSQI questionnaire to measure sleep quality found that the noise that was affected was caused by other people in the room [20]. This could be a factor in the different results because the noise in this study was due to exposure to music at work, where noise exposure occurred before the musician started sleeping.

The determinant factor of musicians' sleep quality was the number of working hours per day (P=0.036). The variables involved in the multivariate analysis contributed 25.9% as risk factors for sleep disturbance (pseudo-R-square 0.25). Other variables may not be analyzed further in this study, including the incidence of NIHL, the volume of in-ear monitors, and sleep hygiene habits [21]. The number of musicians' practice hours was not included in the multivariate analysis due to its effect on changing the significance value of the other variables [22]. This may be due to multicollinearity between the variable number of working hours per day and the number of hours of practice in musicians. For musicians, practice is part of their work. If musicians practice before or outside performance hours, their working hours will increase [23]. No previous research discussed the relationship between musicians' working hours and sleep quality. Most musicians worked at night, similar to night shift workers. Another study on white-collar and blue- collar workers showed that night shifts were associated with sleep disturbances [24]. Night shift workers have difficulty to fall asleep due to disruption of the circadian cycle and reduced sleep hours [24]. This mechanism may underlie the association between the number of working hours and sleep quality among musicians. Based on Indonesian law, the maximum limit for workers to work overtime is 54 hours a week with a weekly break of one day for every six working days in a week. Hopefully, this could be the basis for band managers to implement break times and restrictions on working hours for the sake of musicians' health in conducting their work [25].

Conclusion

No significant relationship is observed between the degree of tinnitus and musicians' sleep quality, while the influencing factors of musicians' sleep quality were the number of working hours per day. Variables of length of work, use of in-ear monitors, use of headsets, use of ear protection devices, type of ear protection devices, age, number of hours of practice per week, number of working hours per day, number of working days per week and average noise exposure are not factors that significantly affected the degree of tinnitus in this study. This study had an inadequate number of samples between each tinnitus category when the bivariate analysis was performed, where several categories had several 0 cells; therefore, recategorization must be done in the analysis process. Initially, this study also used OAE to assess the presence of cochlear outer hair cell damage in musicians but was constrained by the lack of a quiet room to take measurements; therefore, not all subjects underwent OAE. Therefore, OAE results were not analyzed further.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia (Code: KET-793/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Tasya Aulia Praditasari, Marsen Isbayuputra and Dewi Friska; Supervision: Jenny Bashiruddin and Herqutanto; Methodology: Tasya Aulia Praditasari and Dewi Friska; Investigation and data collection: Tasya Aulia Praditasari; Formal Analysis: Tasya Aulia Praditasari and Pukovisa Prawiroharjo; Writing the original draft and project administration: Tasya Aulia Praditasari; Review, editing and resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, for the institutional support provided during the completion of this research.

References

Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external sound source, often in the form of a buzzing, hissing, or ringing sensation in the ears. This condition can be temporary or permanent and is often caused by a disturbance of the hearing system due to noise exposure, as in the case of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Tinnitus affects physiological aspects and significantly impacts the quality of life (QoL), including sleep disturbances, emotional distress, and cognitive difficulties. The exact mechanisms are still not fully understood, but changes in the neural networks that process sound perception are involved. Objective measurement approaches, such as cortical auditory potentials and evaluation of the pre-pulse inhibition response (gap pre-pulse inhibition of the acoustic startle, [GPIAS]), have been introduced to further understand the characteristics of tinnitus, especially to noise exposure and its effects on the sufferers’ QoL.

Noise exposure is one of the most common workplace hazards. A 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) report showed that as many as 1.1 billion people aged 12-35 are at risk of hearing loss due to noise exposure [1]. One of the hearing system disorders due to excessive exposure to loud noise is NIHL [2], and one of the early symptoms of NIHL hearing loss is tinnitus [3]. Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external source, which can be permanent or temporary and is significantly associated with poor QoL, absence from work, and sleep disturbances [4]. Research has shown a relationship between tinnitus and the onset of sleep disturbances. Patients with tinnitus tend to have high Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) scores, and decreased sleep quality correlates with self-reported tinnitus [5].

Occupational noise exposure is the biggest risk factor associated with tinnitus and hearing loss among music industry workers [6]. Musicians perform and practice music regularly and are exposed to high-intensity sounds throughout the day [7]. This puts them at a high risk of developing tinnitus, which can majorly impact their personal and professional lives. Although musicians are at risk of hearing loss and tinnitus, research shows that they are less concerned about these issues [8]. If the symptoms of hearing loss can be detected early, it can favor musicians, maintaining their ability to perform well [9]. However, the literature on tinnitus and sleep quality in musicians is limited. This study aims to investigate the relationship between tinnitus due to music exposure in the workplace and sleep quality, risk factors associated with tinnitus occurrence, and factors associated with the sleep quality of regular professional musicians in Jakarta.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study aimed to determine the relationship between tinnitus due to music exposure in the workplace and sleep quality in musicians. The study was conducted in July 2023 at nine cafes in Jakarta. The study population comprised regular professional musicians in Jakarta who performed music indoors. The inclusion criteria included regular professional musicians aged 18-60 years with the main income (>50% of income) obtained from working as a musician, performed music concerts for at least 2 hours in a week, worked as a regular professional musician for ≥5 years, worked in an indoor venue in Jakarta that performed live music using a sound system speaker, experienced tinnitus within 5 years before collecting research data and provided written consent. The exclusion criteria included uncontrolled medical conditions that interfere with metabolism, sleep, or mood function, history of recurrent otitis media, previous head trauma, infection of the central nervous system, ear, nose, and throat system diseases related to airway obstruction, ear surgery, consumption of ototoxic drugs, and body mass index >35 kg/m2 (severe obesity). The degree of tinnitus was assessed using the tinnitus handicap index (THI) questionnaire, and sleep quality was assessed using the validated PSQI questionnaire, both in the validated Indonesian version. We also conducted otoacoustic. However, Otoacoustic emission (OAE) cannot be performed on all samples because of the lack of a quiet room. Noise measurements were analyzed using a calibrated sound level meter with the Occupational Health Center Hiperkes Jakarta team. The questionnaire was filled out online through Google Forms, which was monitored directly by the researcher. Working hours per day were defined as the number of hours the musician worked per day. Meanwhile practice hours in a week were defined as the number of musician practice hours accumulated in a week; both data were obtained from interviews with the subjects. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25, with a significance level of P<0.05.

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design to investigate the relationship between tinnitus due to workplace music exposure and sleep quality among musicians. Data were collected in July 2023 from nine cafes in Jakarta. The study population included regular professional musicians performing indoor music in Jakarta.

Sampling and data collection

Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method targeting eligible musicians in selected cafes. Eligible participants were contacted and assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The participants were divided into two groups: Those with tinnitus (cases) and those without tinnitus (controls). Sleep quality was compared between the two groups to allow for a descriptive-analytic cross-sectional analysis. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and the recruitment procedure are summarized in Table 1.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 25, with statistical significance at P<0.05. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics, while inferential statistics (e.g. t-tests or chi-square tests) were applied to compare sleep quality between groups. The instruments and measurement procedures used in this study, including THI, PSQI, pure tone audiometry, OAE, and noise measurements, are detailed in Table 2.

Results

This study included 63 musicians who met the inclusion criteria and completed the THI and PSQI questionnaires as well as noise-exposure assessments.

Tinnitus severity distribution

Table 3 presents the distribution of tinnitus handicap categories according to the THI score.

In this sample, 49.2% of the musicians worked as musicians for 5–10 years. Most musicians reported exposure to loud music during work, with the median noise level experienced being 99.8 dB. A total of 49.2% of musicians reported mild tinnitus, while 29.4% experienced moderate tinnitus, and one respondent (1.6%) reported severe tinnitus. The median THI score was 18, categorized as mild.

Respondent characteristics

Table 4 presents the distribution of respondents’ demographic and occupational characteristics.

The median number of working days per week was five, while the median practice hours per week was six. Most musicians never use ear-protection equipment, although 54% reported using in-ear monitors during work. According to the PSQI, 73% of musicians had poor sleep quality with a median total score of 8.

Bivariate analysis between tinnitus and sleep quality

Table 5 shows the bivariate analysis of the relationship between tinnitus severity and musicians’ sleep quality.

There was no significant association between tinnitus severity and sleep quality (P=1.00). However, several occupational factors demonstrated significant relationships with sleep quality. These included years working as a musician, practice hours per week (P=0.02), working hours per day (P=0.03), and the average noise exposure level.

Risk factors associated with musicians’ sleep quality

Table 6 summarizes the risk factors associated with sleep disturbance among musicians.

Upon bivariate analysis, musicians with more practice hours per week and longer working hours per day were significantly more likely to experience poor sleep quality. Additionally, merged variables of sleep quality showed significant associations with musicians’ training hours per week and working hours per day (P=0.00).

Binary logistic regression analysis

Table 7 presents the binary logistic regression analysis outcomes.

The factor that independently influenced sleep quality was the number of working hours per day, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.38 (95% CI, 0.16%, 0.86%). Musicians who worked longer hours were 62% less likely to have good sleep quality. The two significant variables that remained in the multivariable model—sleep quality disturbance and working hours—explained 25.9% of sleep disturbance variance (pseudo R²=0.25).

Tinnitus severity and sleep-quality distribution

Table 8 displays tinnitus levels among musicians with varying sleep-quality outcomes.

Although 72.4% of musicians with mild tinnitus and 80% of those with moderate tinnitus reported poor sleep quality, this difference was not statistically significant (P>0.05). This finding supports the interpretation that sleep disturbance in this population is more strongly influenced by work-related factors than by tinnitus severity.

Discussion

In this study, 49.2% of the respondents had worked as musicians for 5-10 years. The median of the average noise experienced by musicians while working was 99.8 dB, which exceeds the recommended threshold value of 85 dB. Most musicians experienced mild tinnitus (49.2%), and none experienced severe tinnitus [10]. The median THI score was 18, which was categorized as mild. The PSQI questionnaire showed that 73% of musicians had poor sleep quality, with a median score of 8. This study conducted a 12-frequency OAE examination on eight musicians to assess potential damage to the cochlea's outer hair cells [11]. The examination was limited to eight participants due to the lack of a quiet room, as testing in a non-ideal environment could lead to inaccurate results. This limitation restricts the generalizability of the findings and prevents further analysis of OAE data in the context of this study.

In this study, noise exposure had no significant effect on the degree of tinnitus [12]. The amount of noise exposure was represented by average noise, years as a musician, practice hours per week, working hours per day, and working days per week [8]. Further analysis of the degree of tinnitus was conducted, merging musicians' training hours per week and working hours per day [13]. These variables were not significantly related to the degree of tinnitus. Previous studies in military populations have shown no correlation between tinnitus severity and the amount of noise exposure [14]. One factor that may have affected the results of this study is that most tinnitus cases result from NIHL and are accompanied by changes in the central auditory pathway [15]. This study did not examine the presence or absence of musicians' NIHL; therefore, it is not certain whether the noise exposure was significant enough to cause NIHL, which can cause tinnitus [16].

Compared to ear protection devices, musicians prefer in-ear monitors, with 54% of musicians routinely using in-ear monitors during work. In this study, no significant relationship was observed between using in-ear monitors or ear protection devices and tinnitus severity. Until this study was conducted, no research had discussed the relationship between in-ear monitors and ear protection devices and the degree of tinnitus [17]. Factors that may have interfered with the results include that the volume of the musicians' in-ear monitors was not studied further; therefore, the expected protective effect of the in-ear monitor was not significantly observed.

This study showed no significant relationship between the degree of tinnitus and musicians' sleep quality (P=1.00). No previous research has been related to this. Research on tinnitus and sleep quality in the musician population has only examined the relationship between the presence and absence of tinnitus and sleep quality. Previous research suggests no significant difference in sleep quality between musicians with and without tinnitus [18]. Another study in patients with tinnitus showed a significant relationship between moderate and severe degrees of THI and sleep disturbance [17]. In this study, most musicians had very mild (42.9%) and mild (49.2%) tinnitus; therefore, it was possible that the degree of tinnitus was not enough to disturb musicians' sleep quality, and no significant relationship was observed between the degree of tinnitus and musicians’ sleep quality [19].

A significant relationship was observed between the musicians' training hours per week (P=0.000), working hours per day (P=0.036) and musicians' sleep quality. Musicians had uncertain working hours, and practice was part of the work. Rehearsals would increase musicians working hours; therefore, they would work until late at night. This may affect the musician's sleep cycle, ultimately impacting sleep quality [15]. Years as a musician and working days per week were not significantly related to musicians' sleep quality. The problem of musicians' sleep disorders was sleep dissatisfaction [13] and uncertain working hours; therefore, working days in a week and years as a musician did not significantly impact. A possible mechanism is that the longer the time as a musician, the more accustomed they are to perform; therefore, they do not need as many hours of rehearsal, and the number of working hours in a day would be reduced compared to musicians who were still practicing frequently [12].

This study showed no significant relationship between average noise exposure and musicians' sleep quality. Another study that used the PSQI questionnaire to measure sleep quality found that the noise that was affected was caused by other people in the room [20]. This could be a factor in the different results because the noise in this study was due to exposure to music at work, where noise exposure occurred before the musician started sleeping.

The determinant factor of musicians' sleep quality was the number of working hours per day (P=0.036). The variables involved in the multivariate analysis contributed 25.9% as risk factors for sleep disturbance (pseudo-R-square 0.25). Other variables may not be analyzed further in this study, including the incidence of NIHL, the volume of in-ear monitors, and sleep hygiene habits [21]. The number of musicians' practice hours was not included in the multivariate analysis due to its effect on changing the significance value of the other variables [22]. This may be due to multicollinearity between the variable number of working hours per day and the number of hours of practice in musicians. For musicians, practice is part of their work. If musicians practice before or outside performance hours, their working hours will increase [23]. No previous research discussed the relationship between musicians' working hours and sleep quality. Most musicians worked at night, similar to night shift workers. Another study on white-collar and blue- collar workers showed that night shifts were associated with sleep disturbances [24]. Night shift workers have difficulty to fall asleep due to disruption of the circadian cycle and reduced sleep hours [24]. This mechanism may underlie the association between the number of working hours and sleep quality among musicians. Based on Indonesian law, the maximum limit for workers to work overtime is 54 hours a week with a weekly break of one day for every six working days in a week. Hopefully, this could be the basis for band managers to implement break times and restrictions on working hours for the sake of musicians' health in conducting their work [25].

Conclusion

No significant relationship is observed between the degree of tinnitus and musicians' sleep quality, while the influencing factors of musicians' sleep quality were the number of working hours per day. Variables of length of work, use of in-ear monitors, use of headsets, use of ear protection devices, type of ear protection devices, age, number of hours of practice per week, number of working hours per day, number of working days per week and average noise exposure are not factors that significantly affected the degree of tinnitus in this study. This study had an inadequate number of samples between each tinnitus category when the bivariate analysis was performed, where several categories had several 0 cells; therefore, recategorization must be done in the analysis process. Initially, this study also used OAE to assess the presence of cochlear outer hair cell damage in musicians but was constrained by the lack of a quiet room to take measurements; therefore, not all subjects underwent OAE. Therefore, OAE results were not analyzed further.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia (Code: KET-793/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Tasya Aulia Praditasari, Marsen Isbayuputra and Dewi Friska; Supervision: Jenny Bashiruddin and Herqutanto; Methodology: Tasya Aulia Praditasari and Dewi Friska; Investigation and data collection: Tasya Aulia Praditasari; Formal Analysis: Tasya Aulia Praditasari and Pukovisa Prawiroharjo; Writing the original draft and project administration: Tasya Aulia Praditasari; Review, editing and resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, for the institutional support provided during the completion of this research.

References

- Putri BA, Halim RD, Nasution HS. Studi Kualitatif Gangguan pendengaran Akibat bising/Noise Induced Hearing loss (NIHL) pada Marshaller di bandar Udara Sultan Thaha kota Jambi Tahun 2020. J kesmas Jambi. 2021; 5(1):41-53. [DOI:10.22437/jkmj.v5i1.12400]

- Buksh N, Nargis Y, Yun C, He D, Ghufran M. Occupational noise exposure and its impact on worker’s health and activities. Int J Public Heal Clin Sci. 2018; 5(2):180-95. [Link]

- Rhee J, Lee D, Suh MW, Lee JH, Hong YC, Oh SH, et al. Prevalence, associated factors, and comorbidities of tinnitus in adolescents. PLoS One. 2020; 15(7):e0236723. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0236723] [PMID]

- Li YL, Hsu YC, Lin CY, Wu JL. Sleep disturbance and psychological distress in adult patients with tinnitus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022; 121(5):995-1002. [DOI:10.1016/j.jfma.2021.07.022] [PMID]

- Gu H, Kong W, Yin H, Zheng Y. Prevalence of sleep impairment in patients with tinnitus: a systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022; 279(5):2211-21. [DOI:10.1007/s00405-021-07092-x] [PMID]

- Sturges J, Bailey C. Walking back to happiness : The resurgence of latent callings in later life. Hum Relat. 2023;76(8):1256-84. [DOI:10.1177/00187267221095759]

- Di Stadio A, Dipietro L, Ricci G, Della Volpe A, Minni A, Greco A, et al. Hearing loss, tinnitus, hyperacusis, and diplacusis in professional musicians: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(10):2120. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15102120] [PMID]

- Burns-O'Connell G, Stockdale D, Cassidy O, Knowles V, Hoare DJ. Surrounded by Sound: The Impact of tinnitus on musicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9036. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18179036] [PMID]

- Dinakaran T, D RD, RejoyThadathil C. Awareness of musicians on ear protection and tinnitus: A preliminary study. Audiol Res. 2018; 8(1):198. [DOI:10.4081/audiores.2018.198] [PMID]

- Maldonado CJ, White-Phillip JA, Liu Y, Erbele ID, Choi YS. Exposomic Signatures of Tinnitus and/or Hearing Loss. Mil Med. 2023; 188(Suppl 6):102-9. [DOI:10.1093/milmed/usad046] [PMID]

- Totten DJ, Saltagi A, Libich K, Pisoni DB, Nelson RF. Cochlear implantation in US Military Veterans: A single institution study. OTO Open. 2023; 7(2):e53. [DOI:10.1002/oto2.53] [PMID]

- Feder K, Marro L, Portnuff C. Leisure noise exposure and hearing outcomes among Canadians aged 6 to 79 years. Int J Audiol. 2023; 62(11):1031-47. [DOI:10.1080/14992027.2022.2114022] [PMID]

- Stanhope J, Weinstein P. Should musicians play in pain ? Br J Pain. 2021; 15(1):82-90. [DOI:10.1177/2049463720911399] [PMID]

- Dillard LK, Arunda MO, Lopez-Perez L, Martinez RX, Jiménez L, Chadha S. Prevalence and global estimates of unsafe listening practices in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2022; 7(11):e010501. [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010501] [PMID]

- Wang TC, Chang TY, Tyler R, Lin YJ, Liang WM, Shau YW,et al. Noise Induced hearing loss and tinnitus-new research developments and remaining gaps in disease assessment, treatment, and prevention. Brain Sci. 2020; 10(10):732. [DOI:10.3390/brainsci10100732] [PMID]

- Li TF, Cha XD, Wang TY, Liang CQ, Li FZ, Wang SL, et al. A cross-sectional study on predictors of patients' tinnitus severity. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024; 10(3):173-9. [DOI:10.1002/wjo2.151] [PMID]

- Musumano LB, Hatzopoulos S, Fancello V, Bianchini C, Bellini T, Pelucchi S, et al. Hyperacusis: Focus on gender differences: A systematic review. Life. 2023; 13(10):2092. [DOI:10.3390/life13102092] [PMID]

- Stormer CCL, Sorlie T, Stenklev NC. Tinnitus, anxiety, depression and substance abuse in rock musicians a norwegian survey. Int Tinnitus J. 2017; 21(1):50-7. [DOI:10.5935/0946-5448.20170010] [PMID]

- Miller RM, Dunn JA, O'Beirne GA, Whitney SL, Snell DL. Relationships between vestibular issues, noise sensitivity, anxiety and prolonged recovery from mild traumatic brain injury among adults : A scoping review. Brain Inj. 2024; 38(8):607-19. [DOI:10.1080/02699052.2024.2337905] [PMID]

- Marta OFD, Kuo SY, Bloomfield J, Lee HC, Ruhyanudin F, Poynor MY, et al. Gender differences in the relationships between sleep disturbances and academic performance among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020; 85:104270. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104270] [PMID]

- Voglino G, Savatteri A, Gualano MR, Catozzi D, Rousset S, Boietti E, et al. How the reduction of working hours could influence health outcomes: A systematic review of published studies. BMJ Open. 2022; 12(4):e051131. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051131] [PMID]

- Taylor ER, Estevao C, Jarrett L, Woods A, Crane N, Fancourt D, et al. Experiences of acquired brain injury survivors participating in online and hybrid performance arts programmes: An ethnographic study. Arts Health. 2024; 16(2):189-205. [DOI:10.1080/17533015.2023.2226697] [PMID]

- He RL, Liu Y, Tan Q, Wang L. The rare manifestations in tuberculous meningoencephalitis: A review of available literature. Ann Med. 2023; 55(1):342-7. [DOI:10.1080/07853890.2022.2164348] [PMID]

- Brum MCB, Dantas Filho FF, Schnorr CC, Bertoletti OA, Bottega GB, da Costa Rodrigues T. Night shift work, short sleep and obesity. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020; 12:13. [DOI:10.1186/s13098-020-0524-9] [PMID]

- Le M, Šarkić B, Anderson R. Prevalence of tinnitus following non-blast related traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of literature. Brain Inj. 2024; 38(11):859-68. [DOI:10.1080/02699052.2024.2353798] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Audiology

Received: 2024/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/01/7 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2024/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/01/7 | Published: 2025/03/2