Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hamdollahi M H, Torabinezhad F. Investigation, Assessment, and Treatment of Speech and Language Disorders in a Person With Cluttering: A Case Study. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-295-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-295-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Centre, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Centre, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,torabinezhad.f@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Centre, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 511 kb]

(247 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (382 Views)

Full-Text: (112 Views)

Introduction

Cluttering is a speech fluency disorder in which individuals cannot adequately regulate their speech rate according to syntactic or phonological demands [1]. According to Ward, cluttering is a speech and language processing disorder that results in fast, unrhythmic, disorganized, unstructured, and often unclear speech. Although rapid speech does not always occur, language formulation issues are always present. These differences highlight the multifaceted nature of cluttering, making diagnosis challenging [2]. Similar to stuttering, there is currently no known cause for cluttering. Some researchers have suggested a genetic basis for cluttering, and it has been observed that, like stuttering, cluttering tends to run in families. The prevalence of cluttering varies from 0.4% to 11.5% [3]. A European study calculated that the prevalence of cluttering was 1.1% and 1.2% in the Netherlands and Germany, respectively [4]. Additionally, cluttering is more common in men than women, with a ratio of four to one [2].

In a widely accepted definition known as the “lowest common denominator,” proposed by Louis and Schulte, the main criterion for diagnosing cluttering is a speech rate that appears rapid or irregular to the listener. When this criterion is met, at least one of the following three symptoms must also be present to diagnose cluttering [5]:

Natural dysfluencies: Includes phrase-level and word-level repetitions without muscle tension, pauses, and revisions.

Over-coarticulation: Excessive coarticulation in which sounds overlap or are omitted.

Abnormal speech rhythm: Characterized by unusual pauses and stress patterns.

When examining an individual’s cluttering characteristics, two key components are considered: The motor and language components [2].

Motor component characteristics

The following features can be attributed to the motor component of cluttering:

Tachylalia (rapid speech): Although cluttered speech often appears rapid, this perception may stem from sudden impulsive bursts in certain words or phrases that make the speech sound rushed rather than consistently fast.

Articulation errors: Includes distorted sounds, simplifications, and excessive co-articulation.

Loss of speech rhythm: Often identified by staccato-like speech, which appears fragmented.

Repetitions and dysfluencies: Repetitions at the phrase, word, or part-word level, which can sometimes be mistaken for stuttering.

Language component characteristics

The language-related features of cluttering include:

Grammatical and syntactic issues: Difficulties with verb conjugation, improper word order, and incomplete or unfinished sentences.

Word retrieval problems: Challenges in accurately retrieving and using words.

Pragmatic issues: Difficulty maintaining the topic and organizing information coherently in discourse. Cluttered individuals often struggle to focus their thoughts on the sentences they are speaking and may have difficulty connecting sentences logically. Additionally, they often struggle to summarize, order information correctly, and focus on the main topic. These individuals tend to add extraneous phrases and words that do not contribute to the content of their speech [6]. Removing these extra parts does not alter the speech’s overall meaning or content.

Cluttering can often co-occur with other disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, auditory processing issues, reading and learning disorders, and even stuttering [2, 6]. Unlike stuttering, individuals with cluttering are often unaware of their speech issues. Teenagers and adults with cluttering may sometimes recognize a problem but feel unable to address it or may be unaware of their speech’s impact on listeners. As a result, behaviors, such as avoiding speaking situations or feeling anxious about specific sounds or words, are rare in cluttering, and individuals easily participate in everyday conversations. Additionally, when they put extra effort into speaking clearly, they can often manage the problem more effectively [6].

Given these factors, in addition to cluttering being a relatively rare speech fluency disorder, individuals with cluttering do not seek speech therapy or treatment. This lack of engagement has resulted in speech and language pathologists, particularly younger therapists, rarely encountering these clients, leading to limited clinical experience in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of cluttering. Furthermore, a search of research databases suggests that no studies have been conducted in this field in our country to date. However, few case studies on cluttering have been reported in other languages, particularly English. For example, Daly et al. reported a case of a 9-year-old child who was clogged. They used two tools for assessment and diagnosis: A checklist for the possibility of cluttering and a profile analysis form for treatment planning [7]. Although these tools have not been standardized in our country, their use in this study undoubtedly contributed to a more accurate diagnosis.

Healey et al. examined the effectiveness of two therapeutic approaches, pausing and exaggerated stress, in a case report involving a 13-year-old male adolescent with cluttering. The study found that the pausing technique was more effective in reducing over-coarticulation and production errors in a cluttered person [8].

The present study examined the characteristics, assessment methods, and reporting of clinical interventions for addressing speech and language disorders in a person with cluttering, presented in a case report format.

Case Description

The case concerns a 34-year-old man referred to the Avaj Speech Therapy Clinic in Tehran with his sister, who reported stuttering and unclear speech. The assessments conducted by the therapist are as follows:

History taking

Personal and family history

The client was 34 years old, the youngest child in his family, single, and self-employed. His educational background included only primary schooling (he completed fifth grade). During an interview with his family, they could not specify the exact age at which his speech problems began but mentioned that he had been dysfluent since childhood. No family history of speech fluency disorder was reported.

Medical history

The family reported no specific medical diseases or history of neurological disorders or injuries, such as accidents, seizures, or head trauma. Additionally, he was not reported to be on any other medications.

Speech and language history

The client and his family provided limited information regarding his speech and language development. However, he experienced delayed speech onset in childhood. Around age five, he began exhibiting issues, such as word repetition and rapid speech.

Rehabilitation history

The family reported that he had attended speech therapy sessions during his school years, although these sessions were discontinued due to a lack of progress and the family’s financial constraints.

Reason for seeking treatment:

The client’s visit to the clinic was primarily due to his family’s insistence on seeking treament. During the interview, family members expressed concern about his speech problem’s significant impact on his quality of life. They believed that if his speech issues were treated, he could experience improvements in his professional and social life. However, the client was not fully aware of how his speech disorder affected his quality of life.

Speech and language assessments

For more detailed evaluations, speech samples were obtained from the client in the following contexts:

1. Defining daily activities, expressing memories, and talking about the job;

2. Reading simple text: Because the client has a low level of education, he had problems reading even simple texts; therefore, the analysis was performed only in continuous speech.

To diagnose, the speech samples were analyzed by the therapist as follows:

Frequency and type of dysfluencies: The analysis of the client’s speech samples concluded that all dysfluencies are pauses and repetitions at the words, syllables, and sounds level. Also, the percentage of dysfluency was estimated to be 3% by analyzing a 210-syllable sample of the client’s speech in the context of describing daily events. Although the frequency of dysfluencies is not high, the types are consistent with the definitions and characteristics of cluttering.

Rhythm and rate of speech: The rate evaluation in the speech sample was calculated to be 210 syllables per minute, which, according to the average rate of the norm in speech (196 syllables per minute), the client’s speech rate was slightly higher than the standard limit [6]. Although perceptually, the rate of the client’s speech seemed high, the point that was more crucial than the high rate of his speech was the sudden and abundant impulses at the beginning of the client’s utterances, which caused the speech to have a rapid state (tachylalia). Regarding the rhythm and tone of the speech, in addition to the monotony of the prosody, a rasping tone was heard at the end of all the client’s sentences, which significantly negatively affected the natural prosody of the speech.

Analysis of meaningful syllables from extra syllables: To calculate this item, we divided the proportion of syllables that convey the message and meaning by the total number of syllables in the speech sample to determine the amount of filler and extra words in the client’s speech. After analyzing a part of the client’s speech sample (210 syllables), 25 extra syllables were observed in the speech that did not help convey meaning. Therefore, 185 useful syllables were identified, and the ratio of effective syllables conveying meaning to the total number of syllables expressed was 88%. A total of 12% of the statements in the analyzed sample were extra and did not help the meaning.

Language assessment: Due to the lack of official language assessment scales appropriate to the client’s age, only informal assessments were done in this section, analyzing conversational speech samples and picture description contexts. The results of these assessments are as follows:

Phonology: Phonological processes, such as consonant deletion in different parts of words, weak syllable deletion, co-articulation, simplification, and distortion, were observed in the client’s speech.

Syntax: One of the crucial errors in the client’s speech was not paying attention to the grammatical structure of sentences, such as producing sentences without verbs. Also, the sentences were often short and simple, and the client did not use complex sentences in his speech samples.

Semantics: The client’s speech primarily utilized simple and objective words, while abstract terms were used less frequently. Moreover, not only was the expression of abstract words challenging but comprehending these concepts proved difficult.

Pragmatics: One of the specific issues in the client was the inability to organize and maintain the coherence of multiple sentences to continue a conversation or express narratives. In defining daily events, the client mainly expressed a series of simple and repetitive sentences. If the therapist asked a new question about the client’s daily events, the client could not answer appropriately and completely. Also, when describing memories, he usually paid more attention to unimportant details and deviated from telling the story.

Diagnostic process

Based on the evaluation results, the speech characteristics of the client closely aligned with the features commonly associated with cluttering as described in the literature. Certain key points help guide the diagnosis of cluttering in differentiating between cluttering and stuttering [2, 6].

Speech rate: Stuttering typically involves a slow rate, whereas a hallmark of cluttering is rapid and sometimes explosive speech.

Rhythm disruption: In stuttering, rhythm disruptions occur due to fluency breaks interrupting the natural flow of speech. However, rhythm issues are present in cluttering even when no fluency disruptions, such as repetitions.

Types of dysfluencies: Dysfluencies like prolongations and blocks are characteristic of stuttering and are not observed in cluttering. In cluttering, the dysfluency pattern often involves repetitions at the sound, part-word, whole-word, and phrase levels.

Fear and avoidance: Unlike stuttering, cluttering is not associated with fear, avoidance behaviors, or heightened awareness of speech disorders.

Phonological errors: Adult stuttering is typically not accompanied by phonological errors, whereas cluttering may involve such production and phonological errors.

Language impairments: Stuttering does not involve language impairments (especially in adults), whereas one of the defining features of cluttering is difficulty in formulating linguistic structures.

To ensure diagnostic accuracy, the center consulted another speech and language pathologist specializing in stuttering treatment. After reviewing the evaluation results and observing the client during the session, this colleague also concurred with the diagnosis of cluttering.

Prognosis and intervention plan

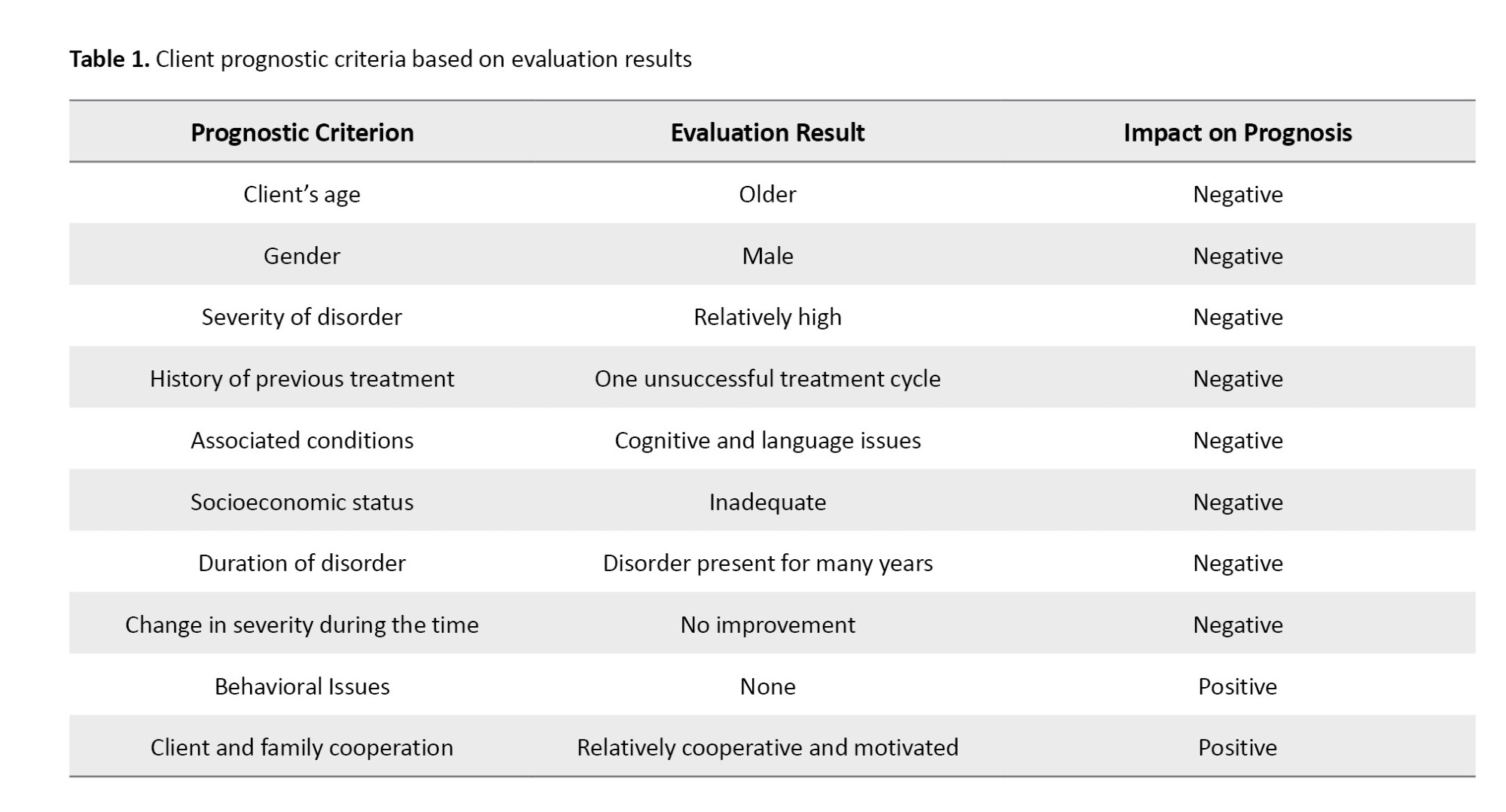

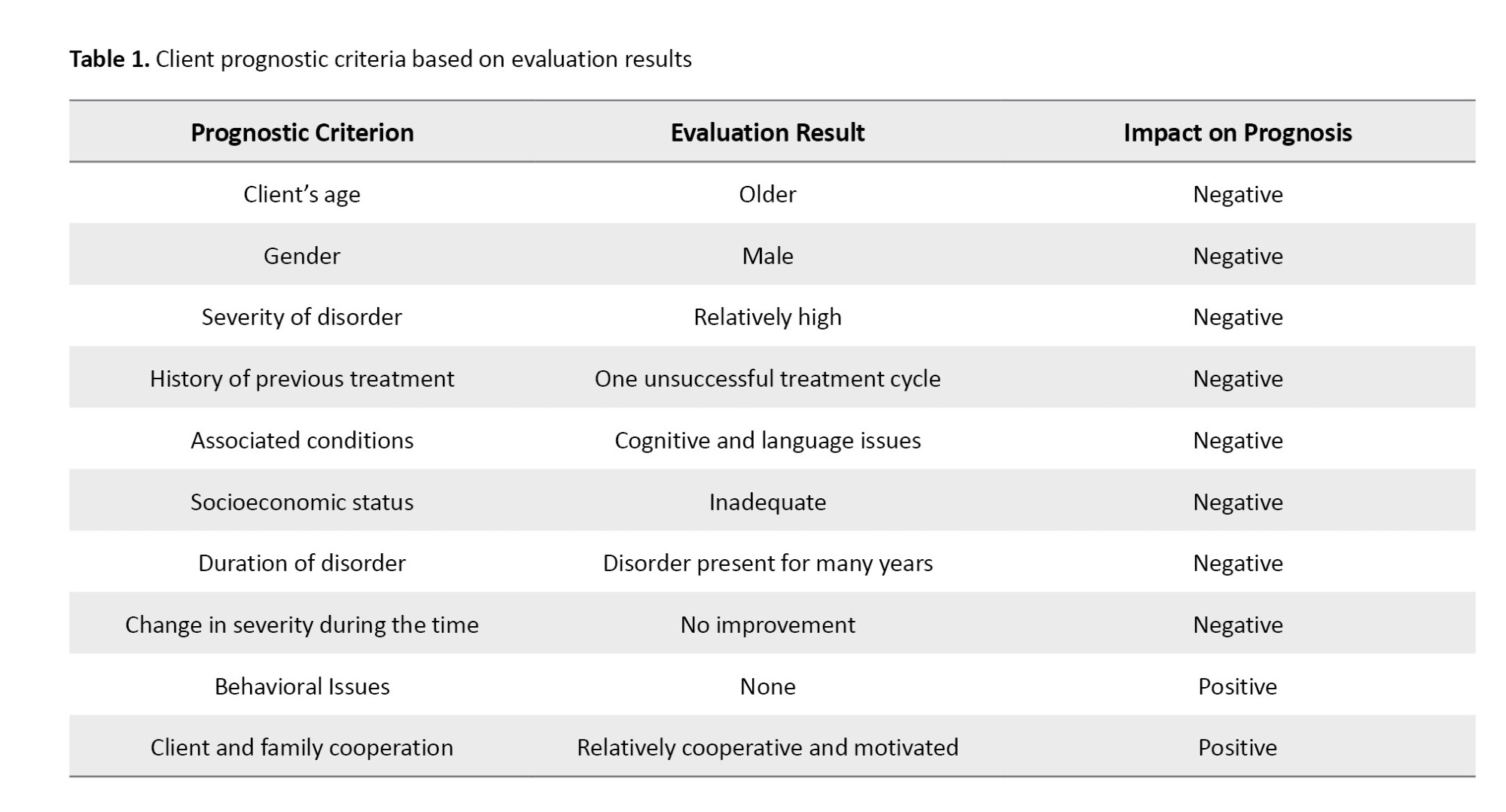

Based on the evaluation results, several factors were identified to assess prognosis (Table 1). A favorable prognosis was not anticipated, but the client’s family demonstrated high motivation, and the client showed relatively good cooperation. The following goals and intervention plans were considered for treatment:

Enhancing client awareness of speech problems; strengthening self-monitoring skills; correcting inappropriate speech patterns; generalizing learned techniques to various communication situations for daily interaction improvement.

Enhancing awareness of the speech problems

The following activities were considered to raise the clients’ awareness of their speech issues:

Explaining the client’s condition: First, a detailed explanation of the client’s speech disorder was provided, clarifying the differences between cluttering, stuttering, and other speech disorders.

Raising awareness of speech patterns through auditory feedback: We used auditory feedback (recording and playback of the client’s speech) to help the client recognize specific issues in their speech. These recordings highlighted features, such as a high speech rate, repetitions, explosive word onsets, and extraneous filler words. This exercise helped the client identify problematic behaviors in their speech.

Strengthening self-monitoring

To build the client’s self-monitoring skills, we asked him to actively identify and monitor cluttering patterns in his speech. This exercise increases the client’s sensitivity and awareness of cluttering behaviors, such as high speech rate and co-articulation. Auditory feedback through voice recording was also helpful at this stage.

Correcting speech characteristics

Fluency-shaping techniques were employed to modify cluttering speech patterns, especially in reducing speech rate, explosive onsets, and repetitions. A key recommendation was to address speech rate reduction as a fundamental part of the intervention, as slowing down can improve speech clarity and reduce articulation errors.

Generalizing techniques to other speaking situations

One common challenge in treatment is the limited generalization of learned techniques to different speaking environments. To address this, a hierarchy of speech situations outside therapy sessions was created, encouraging the client to gradually apply fluency-shaping techniques in varied contexts. This application was monitored through recorded speech samples, family reports, and client self-reports shared with the therapist.

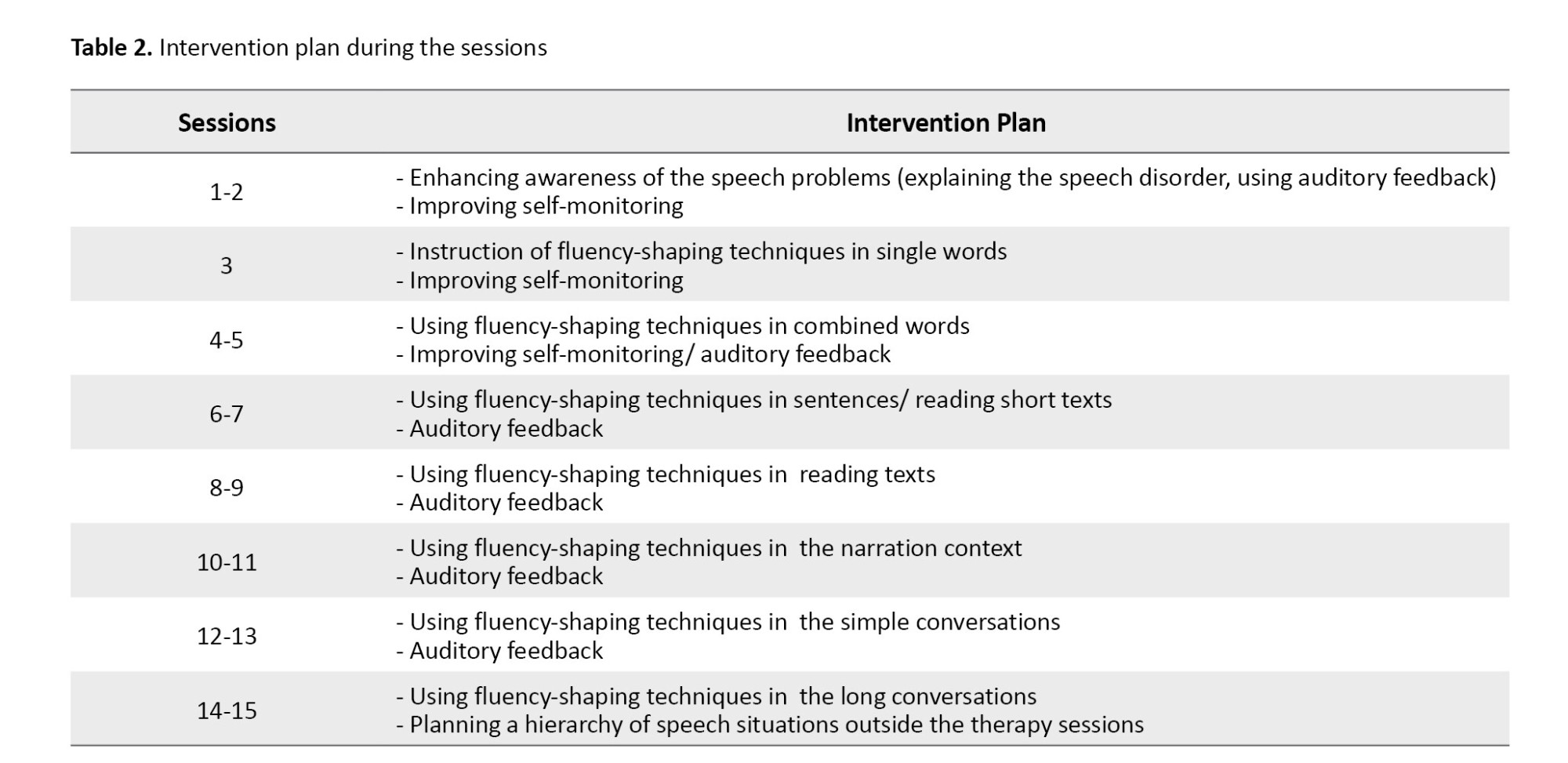

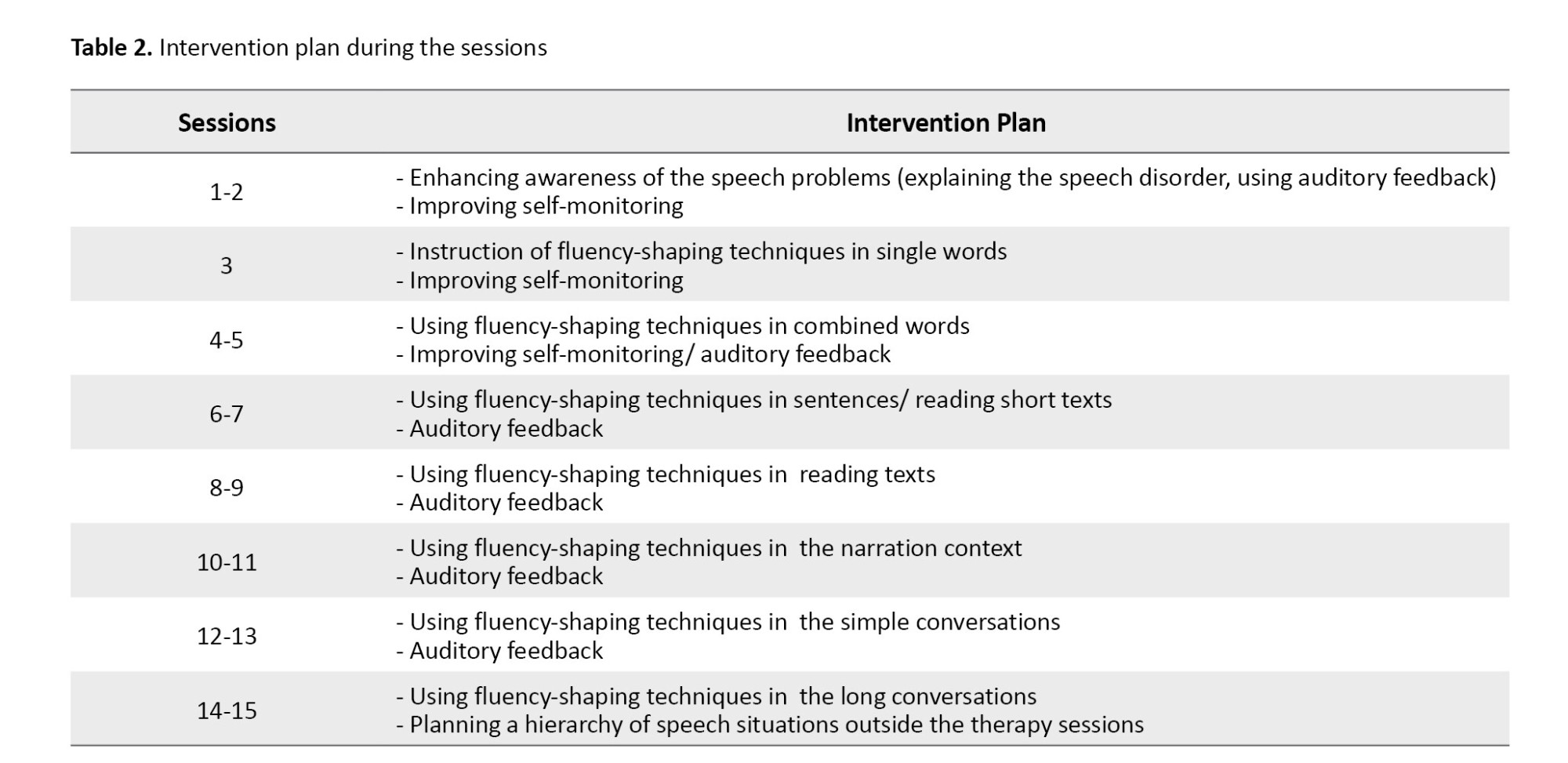

The client participated in 15 weekly intervention sessions, each lasting between 30 and 45 minutes. The initial sessions aimed to enhance the client’s awareness of their speech disorder and develop self-monitoring skills. Subsequently, the client was introduced to a speech pattern that emphasized slow-paced, melodic speech. The speech pattern instruction began with simple vocabulary and progressed to continuous speech by the end of the treatment period. In the final session, we discussed how to apply the learned speech patterns in various speaking situations with the client. Table 2 presents detailed descriptions of the interventions conducted in each session.

Post-intervention evaluation

The exercises utilized sentences and texts from preschool children’s storybooks to facilitate the client’s reading. The treatment approach involves gradually helping the client stabilize the method of slowing down speech rate and using a melodic tone. Each time clients mastered a level, they progressed to the next stage.

By the eleventh session, the client had effectively applied the taught methods to describe everyday events, and the thirteenth session consolidated this proficiency. By the end of the fifteenth session, the client demonstrated good control over speech rate. Additionally, enhancing self-monitoring skills led to a significant reduction in articulation errors and increased speech clarity.

However, despite positive progress after 15 intervention sessions, generalization of the learned speech patterns to other speaking contexts remained limited.

Discussion

This case study is the first report on written cluttering in Iran. In this study, beyond examining the speech and language characteristics of a person with cluttering, assessment procedures, and therapeutic approaches were also reviewed. This report offers valuable insights for researchers and therapists regarding the symptoms and characteristics of cluttering. A significant finding from the examination of speech and language traits in patients with cluttering is that they exhibit notable language deficits in addition to distinct speech characteristics. This observation aligns well with other studies and sources in the field [2, 6]. While this is the first case report on cluttering in Iran, research has been conducted internationally.

Hashimoto et al. reported a 57-year-old woman with dementia who gradually exhibited cluttering-like symptoms as her condition progressed. These symptoms included monotone speech and a very high speech rate, which became even faster toward the end of sentences, easily skipping over several syllables and words [9]. In this case, the symptoms were consistent with those of St. Louis’s definition of cluttering and share some characteristics observed in the present study, highlighting the significance of speech rhythm and rate as core features of cluttering.

In another study, Scott compared cluttering symptoms among school-aged children with cluttering to those of typically developing children across different contexts, including monologue, conversation, and expository discourse. The results indicated two primary features in the childeren’s speech with cluttering: Excessive co-articulation and natural dysfluencies, including repetitions [10]. These characteristics are also highlighted in the current case report.

Daly et al. reported a case of a 9-year-old child with cluttering. They utilized two tools for assessment and diagnosis: “A checklist for possible cluttering” and a “profile analysis for treatment planning” [7]. Van Borsel et al. also employed a “predictive cluttering inventory” to identify cluttering features in 76 individuals with Down syndrome, aged 3.8 to 57.3 years [11]. Although their study found that this tool was ineffective in the Down syndrome population, the use of such tools in research contributes to more precise diagnosis. In the current study, informal assessments and consultations with another speech-language pathologist specializing in fluency disorders were used for diagnosis due to the absence of standardized tools in Persian.

Regarding therapeutic approaches, several studies have provided methods that can be compared to the treatment approaches suggested in this case. Marriner et al. applied a behavioral treatment approach to a 26-year-old woman with cluttering at a psychiatric hospital in Australia. The program, jointly designed by a clinical psychologist and a hospital speech-language pathologist, targeted three specific areas: Dominance (measured as the number of verbal interactions in 5-second segments), appropriate responses to interruption, and speech rate (syllables per minute). Techniques included visual feedback through syllable counters and graphs to reduce speech rate, explanations regarding interruptions, and training the client to ask questions appropriately. The results showed that this intervention effectively reduced cluttering behaviors in the client [12].

In a recent study, Healey et al. assessed the effectiveness of two therapeutic approaches, pause, and excessive emphasis, in a 13-year-old boy with cluttering. Their results indicated that the pause method was more effective in reducing excessive co-articulations and articulation errors in cluttering [8]. In the present study, the post-test assessments indicated that interventions for speech rate reduction and improving self-monitoring could be beneficial in reducing co-articulation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study attempted to describe speech and language characteristics and conduct an intervention for a person with Persian-language cluttering. Since research on cluttering remains limited, this study’s results could stimulate future studies and investigations. Furthermore, the results can help identify differentiate these clients from stuttering.

Despite this study’s numerous limitations and challenges, such as the lack of standardized assessment tools and the therapist’s limited experience with cluttering cases, the results could serve as a foundation for further research in this relatively unexplored area. Subsequent research by speech-language pathologists should focus on evaluating the efficacy of different therapeutic approaches and standardizing cluttering diagnostic tools.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Consent was obtained from both the client and his family for the study report.

Funding

This study was extracted from the research project of Mohammad Hossein Hamdollahi, approved by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Farhad Torabinezhad; Methodology, writing, editing, and final approval: All Authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the client and their family for allowing the publication of these detailed findings.

References

Cluttering is a speech fluency disorder in which individuals cannot adequately regulate their speech rate according to syntactic or phonological demands [1]. According to Ward, cluttering is a speech and language processing disorder that results in fast, unrhythmic, disorganized, unstructured, and often unclear speech. Although rapid speech does not always occur, language formulation issues are always present. These differences highlight the multifaceted nature of cluttering, making diagnosis challenging [2]. Similar to stuttering, there is currently no known cause for cluttering. Some researchers have suggested a genetic basis for cluttering, and it has been observed that, like stuttering, cluttering tends to run in families. The prevalence of cluttering varies from 0.4% to 11.5% [3]. A European study calculated that the prevalence of cluttering was 1.1% and 1.2% in the Netherlands and Germany, respectively [4]. Additionally, cluttering is more common in men than women, with a ratio of four to one [2].

In a widely accepted definition known as the “lowest common denominator,” proposed by Louis and Schulte, the main criterion for diagnosing cluttering is a speech rate that appears rapid or irregular to the listener. When this criterion is met, at least one of the following three symptoms must also be present to diagnose cluttering [5]:

Natural dysfluencies: Includes phrase-level and word-level repetitions without muscle tension, pauses, and revisions.

Over-coarticulation: Excessive coarticulation in which sounds overlap or are omitted.

Abnormal speech rhythm: Characterized by unusual pauses and stress patterns.

When examining an individual’s cluttering characteristics, two key components are considered: The motor and language components [2].

Motor component characteristics

The following features can be attributed to the motor component of cluttering:

Tachylalia (rapid speech): Although cluttered speech often appears rapid, this perception may stem from sudden impulsive bursts in certain words or phrases that make the speech sound rushed rather than consistently fast.

Articulation errors: Includes distorted sounds, simplifications, and excessive co-articulation.

Loss of speech rhythm: Often identified by staccato-like speech, which appears fragmented.

Repetitions and dysfluencies: Repetitions at the phrase, word, or part-word level, which can sometimes be mistaken for stuttering.

Language component characteristics

The language-related features of cluttering include:

Grammatical and syntactic issues: Difficulties with verb conjugation, improper word order, and incomplete or unfinished sentences.

Word retrieval problems: Challenges in accurately retrieving and using words.

Pragmatic issues: Difficulty maintaining the topic and organizing information coherently in discourse. Cluttered individuals often struggle to focus their thoughts on the sentences they are speaking and may have difficulty connecting sentences logically. Additionally, they often struggle to summarize, order information correctly, and focus on the main topic. These individuals tend to add extraneous phrases and words that do not contribute to the content of their speech [6]. Removing these extra parts does not alter the speech’s overall meaning or content.

Cluttering can often co-occur with other disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, auditory processing issues, reading and learning disorders, and even stuttering [2, 6]. Unlike stuttering, individuals with cluttering are often unaware of their speech issues. Teenagers and adults with cluttering may sometimes recognize a problem but feel unable to address it or may be unaware of their speech’s impact on listeners. As a result, behaviors, such as avoiding speaking situations or feeling anxious about specific sounds or words, are rare in cluttering, and individuals easily participate in everyday conversations. Additionally, when they put extra effort into speaking clearly, they can often manage the problem more effectively [6].

Given these factors, in addition to cluttering being a relatively rare speech fluency disorder, individuals with cluttering do not seek speech therapy or treatment. This lack of engagement has resulted in speech and language pathologists, particularly younger therapists, rarely encountering these clients, leading to limited clinical experience in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of cluttering. Furthermore, a search of research databases suggests that no studies have been conducted in this field in our country to date. However, few case studies on cluttering have been reported in other languages, particularly English. For example, Daly et al. reported a case of a 9-year-old child who was clogged. They used two tools for assessment and diagnosis: A checklist for the possibility of cluttering and a profile analysis form for treatment planning [7]. Although these tools have not been standardized in our country, their use in this study undoubtedly contributed to a more accurate diagnosis.

Healey et al. examined the effectiveness of two therapeutic approaches, pausing and exaggerated stress, in a case report involving a 13-year-old male adolescent with cluttering. The study found that the pausing technique was more effective in reducing over-coarticulation and production errors in a cluttered person [8].

The present study examined the characteristics, assessment methods, and reporting of clinical interventions for addressing speech and language disorders in a person with cluttering, presented in a case report format.

Case Description

The case concerns a 34-year-old man referred to the Avaj Speech Therapy Clinic in Tehran with his sister, who reported stuttering and unclear speech. The assessments conducted by the therapist are as follows:

History taking

Personal and family history

The client was 34 years old, the youngest child in his family, single, and self-employed. His educational background included only primary schooling (he completed fifth grade). During an interview with his family, they could not specify the exact age at which his speech problems began but mentioned that he had been dysfluent since childhood. No family history of speech fluency disorder was reported.

Medical history

The family reported no specific medical diseases or history of neurological disorders or injuries, such as accidents, seizures, or head trauma. Additionally, he was not reported to be on any other medications.

Speech and language history

The client and his family provided limited information regarding his speech and language development. However, he experienced delayed speech onset in childhood. Around age five, he began exhibiting issues, such as word repetition and rapid speech.

Rehabilitation history

The family reported that he had attended speech therapy sessions during his school years, although these sessions were discontinued due to a lack of progress and the family’s financial constraints.

Reason for seeking treatment:

The client’s visit to the clinic was primarily due to his family’s insistence on seeking treament. During the interview, family members expressed concern about his speech problem’s significant impact on his quality of life. They believed that if his speech issues were treated, he could experience improvements in his professional and social life. However, the client was not fully aware of how his speech disorder affected his quality of life.

Speech and language assessments

For more detailed evaluations, speech samples were obtained from the client in the following contexts:

1. Defining daily activities, expressing memories, and talking about the job;

2. Reading simple text: Because the client has a low level of education, he had problems reading even simple texts; therefore, the analysis was performed only in continuous speech.

To diagnose, the speech samples were analyzed by the therapist as follows:

Frequency and type of dysfluencies: The analysis of the client’s speech samples concluded that all dysfluencies are pauses and repetitions at the words, syllables, and sounds level. Also, the percentage of dysfluency was estimated to be 3% by analyzing a 210-syllable sample of the client’s speech in the context of describing daily events. Although the frequency of dysfluencies is not high, the types are consistent with the definitions and characteristics of cluttering.

Rhythm and rate of speech: The rate evaluation in the speech sample was calculated to be 210 syllables per minute, which, according to the average rate of the norm in speech (196 syllables per minute), the client’s speech rate was slightly higher than the standard limit [6]. Although perceptually, the rate of the client’s speech seemed high, the point that was more crucial than the high rate of his speech was the sudden and abundant impulses at the beginning of the client’s utterances, which caused the speech to have a rapid state (tachylalia). Regarding the rhythm and tone of the speech, in addition to the monotony of the prosody, a rasping tone was heard at the end of all the client’s sentences, which significantly negatively affected the natural prosody of the speech.

Analysis of meaningful syllables from extra syllables: To calculate this item, we divided the proportion of syllables that convey the message and meaning by the total number of syllables in the speech sample to determine the amount of filler and extra words in the client’s speech. After analyzing a part of the client’s speech sample (210 syllables), 25 extra syllables were observed in the speech that did not help convey meaning. Therefore, 185 useful syllables were identified, and the ratio of effective syllables conveying meaning to the total number of syllables expressed was 88%. A total of 12% of the statements in the analyzed sample were extra and did not help the meaning.

Language assessment: Due to the lack of official language assessment scales appropriate to the client’s age, only informal assessments were done in this section, analyzing conversational speech samples and picture description contexts. The results of these assessments are as follows:

Phonology: Phonological processes, such as consonant deletion in different parts of words, weak syllable deletion, co-articulation, simplification, and distortion, were observed in the client’s speech.

Syntax: One of the crucial errors in the client’s speech was not paying attention to the grammatical structure of sentences, such as producing sentences without verbs. Also, the sentences were often short and simple, and the client did not use complex sentences in his speech samples.

Semantics: The client’s speech primarily utilized simple and objective words, while abstract terms were used less frequently. Moreover, not only was the expression of abstract words challenging but comprehending these concepts proved difficult.

Pragmatics: One of the specific issues in the client was the inability to organize and maintain the coherence of multiple sentences to continue a conversation or express narratives. In defining daily events, the client mainly expressed a series of simple and repetitive sentences. If the therapist asked a new question about the client’s daily events, the client could not answer appropriately and completely. Also, when describing memories, he usually paid more attention to unimportant details and deviated from telling the story.

Diagnostic process

Based on the evaluation results, the speech characteristics of the client closely aligned with the features commonly associated with cluttering as described in the literature. Certain key points help guide the diagnosis of cluttering in differentiating between cluttering and stuttering [2, 6].

Speech rate: Stuttering typically involves a slow rate, whereas a hallmark of cluttering is rapid and sometimes explosive speech.

Rhythm disruption: In stuttering, rhythm disruptions occur due to fluency breaks interrupting the natural flow of speech. However, rhythm issues are present in cluttering even when no fluency disruptions, such as repetitions.

Types of dysfluencies: Dysfluencies like prolongations and blocks are characteristic of stuttering and are not observed in cluttering. In cluttering, the dysfluency pattern often involves repetitions at the sound, part-word, whole-word, and phrase levels.

Fear and avoidance: Unlike stuttering, cluttering is not associated with fear, avoidance behaviors, or heightened awareness of speech disorders.

Phonological errors: Adult stuttering is typically not accompanied by phonological errors, whereas cluttering may involve such production and phonological errors.

Language impairments: Stuttering does not involve language impairments (especially in adults), whereas one of the defining features of cluttering is difficulty in formulating linguistic structures.

To ensure diagnostic accuracy, the center consulted another speech and language pathologist specializing in stuttering treatment. After reviewing the evaluation results and observing the client during the session, this colleague also concurred with the diagnosis of cluttering.

Prognosis and intervention plan

Based on the evaluation results, several factors were identified to assess prognosis (Table 1). A favorable prognosis was not anticipated, but the client’s family demonstrated high motivation, and the client showed relatively good cooperation. The following goals and intervention plans were considered for treatment:

Enhancing client awareness of speech problems; strengthening self-monitoring skills; correcting inappropriate speech patterns; generalizing learned techniques to various communication situations for daily interaction improvement.

Enhancing awareness of the speech problems

The following activities were considered to raise the clients’ awareness of their speech issues:

Explaining the client’s condition: First, a detailed explanation of the client’s speech disorder was provided, clarifying the differences between cluttering, stuttering, and other speech disorders.

Raising awareness of speech patterns through auditory feedback: We used auditory feedback (recording and playback of the client’s speech) to help the client recognize specific issues in their speech. These recordings highlighted features, such as a high speech rate, repetitions, explosive word onsets, and extraneous filler words. This exercise helped the client identify problematic behaviors in their speech.

Strengthening self-monitoring

To build the client’s self-monitoring skills, we asked him to actively identify and monitor cluttering patterns in his speech. This exercise increases the client’s sensitivity and awareness of cluttering behaviors, such as high speech rate and co-articulation. Auditory feedback through voice recording was also helpful at this stage.

Correcting speech characteristics

Fluency-shaping techniques were employed to modify cluttering speech patterns, especially in reducing speech rate, explosive onsets, and repetitions. A key recommendation was to address speech rate reduction as a fundamental part of the intervention, as slowing down can improve speech clarity and reduce articulation errors.

Generalizing techniques to other speaking situations

One common challenge in treatment is the limited generalization of learned techniques to different speaking environments. To address this, a hierarchy of speech situations outside therapy sessions was created, encouraging the client to gradually apply fluency-shaping techniques in varied contexts. This application was monitored through recorded speech samples, family reports, and client self-reports shared with the therapist.

The client participated in 15 weekly intervention sessions, each lasting between 30 and 45 minutes. The initial sessions aimed to enhance the client’s awareness of their speech disorder and develop self-monitoring skills. Subsequently, the client was introduced to a speech pattern that emphasized slow-paced, melodic speech. The speech pattern instruction began with simple vocabulary and progressed to continuous speech by the end of the treatment period. In the final session, we discussed how to apply the learned speech patterns in various speaking situations with the client. Table 2 presents detailed descriptions of the interventions conducted in each session.

Post-intervention evaluation

The exercises utilized sentences and texts from preschool children’s storybooks to facilitate the client’s reading. The treatment approach involves gradually helping the client stabilize the method of slowing down speech rate and using a melodic tone. Each time clients mastered a level, they progressed to the next stage.

By the eleventh session, the client had effectively applied the taught methods to describe everyday events, and the thirteenth session consolidated this proficiency. By the end of the fifteenth session, the client demonstrated good control over speech rate. Additionally, enhancing self-monitoring skills led to a significant reduction in articulation errors and increased speech clarity.

However, despite positive progress after 15 intervention sessions, generalization of the learned speech patterns to other speaking contexts remained limited.

Discussion

This case study is the first report on written cluttering in Iran. In this study, beyond examining the speech and language characteristics of a person with cluttering, assessment procedures, and therapeutic approaches were also reviewed. This report offers valuable insights for researchers and therapists regarding the symptoms and characteristics of cluttering. A significant finding from the examination of speech and language traits in patients with cluttering is that they exhibit notable language deficits in addition to distinct speech characteristics. This observation aligns well with other studies and sources in the field [2, 6]. While this is the first case report on cluttering in Iran, research has been conducted internationally.

Hashimoto et al. reported a 57-year-old woman with dementia who gradually exhibited cluttering-like symptoms as her condition progressed. These symptoms included monotone speech and a very high speech rate, which became even faster toward the end of sentences, easily skipping over several syllables and words [9]. In this case, the symptoms were consistent with those of St. Louis’s definition of cluttering and share some characteristics observed in the present study, highlighting the significance of speech rhythm and rate as core features of cluttering.

In another study, Scott compared cluttering symptoms among school-aged children with cluttering to those of typically developing children across different contexts, including monologue, conversation, and expository discourse. The results indicated two primary features in the childeren’s speech with cluttering: Excessive co-articulation and natural dysfluencies, including repetitions [10]. These characteristics are also highlighted in the current case report.

Daly et al. reported a case of a 9-year-old child with cluttering. They utilized two tools for assessment and diagnosis: “A checklist for possible cluttering” and a “profile analysis for treatment planning” [7]. Van Borsel et al. also employed a “predictive cluttering inventory” to identify cluttering features in 76 individuals with Down syndrome, aged 3.8 to 57.3 years [11]. Although their study found that this tool was ineffective in the Down syndrome population, the use of such tools in research contributes to more precise diagnosis. In the current study, informal assessments and consultations with another speech-language pathologist specializing in fluency disorders were used for diagnosis due to the absence of standardized tools in Persian.

Regarding therapeutic approaches, several studies have provided methods that can be compared to the treatment approaches suggested in this case. Marriner et al. applied a behavioral treatment approach to a 26-year-old woman with cluttering at a psychiatric hospital in Australia. The program, jointly designed by a clinical psychologist and a hospital speech-language pathologist, targeted three specific areas: Dominance (measured as the number of verbal interactions in 5-second segments), appropriate responses to interruption, and speech rate (syllables per minute). Techniques included visual feedback through syllable counters and graphs to reduce speech rate, explanations regarding interruptions, and training the client to ask questions appropriately. The results showed that this intervention effectively reduced cluttering behaviors in the client [12].

In a recent study, Healey et al. assessed the effectiveness of two therapeutic approaches, pause, and excessive emphasis, in a 13-year-old boy with cluttering. Their results indicated that the pause method was more effective in reducing excessive co-articulations and articulation errors in cluttering [8]. In the present study, the post-test assessments indicated that interventions for speech rate reduction and improving self-monitoring could be beneficial in reducing co-articulation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study attempted to describe speech and language characteristics and conduct an intervention for a person with Persian-language cluttering. Since research on cluttering remains limited, this study’s results could stimulate future studies and investigations. Furthermore, the results can help identify differentiate these clients from stuttering.

Despite this study’s numerous limitations and challenges, such as the lack of standardized assessment tools and the therapist’s limited experience with cluttering cases, the results could serve as a foundation for further research in this relatively unexplored area. Subsequent research by speech-language pathologists should focus on evaluating the efficacy of different therapeutic approaches and standardizing cluttering diagnostic tools.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Consent was obtained from both the client and his family for the study report.

Funding

This study was extracted from the research project of Mohammad Hossein Hamdollahi, approved by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Farhad Torabinezhad; Methodology, writing, editing, and final approval: All Authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the client and their family for allowing the publication of these detailed findings.

References

- van Zaalen Y, Reichel IK. Cluttering treatment: Theoretical considerations and intervention planning. Perspect Glob Issues Commun Sci Relat Disord. 2014; 4(2):57-62. [DOI:10.1044/gics4.2.57]

- Ward D. Stuttering and cluttering: Frameworks for understanding and treatment. London: Psychology Press; 2017. [Link]

- Van Zaalen Y, Reichel I. An introduction to cluttering: A practical guide for speech-language pathology students, clinicians, and researchers.London: Routledge; 2024. [DOI:10.4324/9781003460558]

- Van Zaalen Y, Reichel I. Prevalence of cluttering in two European countries: A pilot study. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups. 2017; 2(17):42-9. [DOI:10.1044/persp2.SIG17.42]

- Louis KO, Schulte K. Defining cluttering: The lowest common denominator. In: Ward D, Scaler Scott K, editors. Cluttering. London: Psychology Press; 2011. [Link]

- Guitar B. Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment. Pennsylvania: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. [Link]

- Daly DA, Burnett ML. Cluttering: Assessment, treatment planning, and case study illustration. J Fluency Disord. 1996; 21(3-4):239-48. [DOI:10.1016/S0094-730X(96)00026-5]

- Healey KT, Nelson S, Scott KS. A case study of cluttering treatment outcomes in a teen. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015; 193:141-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.253]

- Hashimoto R, Taguchi T, Kano M, Hanyu S, Tanaka Y, Nishizawa M, et al. [A case report of dementia with cluttering-like speech disorder and apraxia of gait (Japanese)]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1999; 39(5):520-6. [PMID]

- Scott KS. Cluttering symptoms in school-age children by communicative context: A preliminary investigation. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020; 22(2):174-83. [DOI:10.1080/17549507.2019.1637020] [PMID]

- Van Borsel J, Vandermeulen A. Cluttering in Down syndrome. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2008; 60(6):312-7. [DOI:10.1159/000170081] [PMID]

- Marriner NA, Sanson-Fisher RW. A behavioural approach to cluttering: A case study. Australian J Hum Commun Disord. 1977; 5(2):134-41. [DOI:10.3109/asl2.1977.5.issue-2.10]

Type of Study: Case Report |

Subject:

Speech Therapy

Received: 2024/11/24 | Accepted: 2025/01/18 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2024/11/24 | Accepted: 2025/01/18 | Published: 2025/03/2