Volume 8, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

Func Disabil J 2025, 8(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Pandita R. Understanding the Unmet Needs of Epilepsy in Indian population. Func Disabil J 2025; 8 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-288-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-288-en.html

Department of Management Studies, School of Business Management, Indus University, Ahmedabad, India. , rajesh.eris1@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 689 kb]

(380 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1562 Views)

Full-Text: (257 Views)

Introduction

India is one of the most diverse and populous countries in the world, where people of different beliefs live in different parts of the country, and it is difficult to impress the common Indians with disease awareness and its impact on society. Epilepsy is a severe brain disorder that affects 1% of the world’s population and has a significant impact on people’s quality of life (QoL), especially those with wholly controlled seizures [1].

Epilepsy has multiple causes and is multifactorial. It occurs when clusters of nerves in the brain send out abnormal signals to the rest of the brain. Anything that disrupts the typical patterns of nerve activity, from disease to brain injury to abnormal brain growth, can cause seizures [2].

Most people in our societies consider neurological disorders as taboo in India. We do not want to talk about them, and people do not understand how sensitive it is. The patient used to say, “Epilepsy cannot happen to me.” Like all of us here, the patient denied it. According to reported cases in India, nearly one-sixth of the people with epilepsy (PWE) worldwide live in India. A person with epilepsy may develop epilepsy due to abnormal wiring in the brain, an imbalance in nerve signaling chemicals known as neurotransmitters in the brain, changes in essential features of the brain’s membrane receptors and channels, or a combination of those and other factors.

India is one of the largest South Asian countries, with a population of over 1.3 billion people belonging to various castes and creeds, with various social and cultural backgrounds, and socio-economic classes. In India, people have different opinions, beliefs, perceptions, and knowledge about various situations.

One of the main issues we face in this article is the awareness, knowledge, and belief about epilepsy. Epilepsy is a chronic, non-infectious brain disease. It is characterized by repeated seizures, sometimes resulting in unconsciousness and involuntary movement of the bowel and bladder. Epilepsy can be treated with medication or surgery [3, 4].

World Health Organisation (WHO) recently reported that 80% of epileptic patients live in low and middle-class countries. Epilepsy is not contagious. While many underlying disease mechanisms can cause epilepsy, the underlying cause of epilepsy is still unknown in approximately 50% of cases worldwide. Still, 12% of the surveyed urban population believed that epilepsy does not originate from the brain, as shown in Figure 1.

.PNG)

Epilepsy causes can be classified into structural, genuine, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown. Some common causes of epilepsy include:

● Brain damage from prenatal and perinatal conditions (e.g. oxygen deprivation or trauma during birth, low birth weight)

● Congenital abnormality or genetic conditions with brain malformations

● Severe head injury

● Stroke that limits the oxygen to the brain

● Infection of the brain (including meningitis and encephalitis, specific genetic syndromes)

● Brain tumour

According to some estimates, as many as 70% of PWE could live seizure-free if diagnosed and treated correctly [5].

This issue suggests that more exhaustive studies should be conducted to assess the actual prevalence of epilepsy in India.

Epilepsy is one of the most common medical conditions in that PWE do not seek treatment from a professional. Some of the reasons why people do not seek treatment for epilepsy are:

● People have negative attitudes towards the help available.

● People are concerned about the cost of treatment.

● People are worried about transportation or inconvenience.

● People are afraid of breach of confidentiality.

● People feel like they can manage the problem alone.

● Traditional healers are one of the leading providers of treatment for epilepsy in India.

● People who believe in the supernatural cause of epilepsy mainly seek treatment from indigenous healers in India.

● Many people do not receive epilepsy treatment due to delay in initiation.

● Many people in the community do not receive treatment for epilepsy.

The myths and misunderstandings about epilepsy also affect the patient’s health. For example, due to the belief in superstitions and supernatural powers, patients are often forced to rely on religious healing and traditional treatments that can damage their health [6].

Epilepsy has a detrimental impact on educational attainment, employment, marital status, and other fundamental social relationships. The economic burden of epilepsy is exceptionally high, with the cost of treatment and travel is a significant factor. This culminates in a vicious cycle of economic burden and inadequate disease outcomes [6]. Public awareness campaigns and allocated disease days should be implemented because they play a vital role in eliminating the stigma and misperceptions associated with epilepsy.

In the Indian urban population, only 52% knew that medications are available that can well manage the epilepsy condition and that PWE can live a seizure-free life, and 48% believed that medications are unavailable that can help a person with epilepsy live seizure-free life, as shown in Figure 2.

.PNG)

It is remarkable that, even though approximately 12 million individuals in India are affected by epilepsy, this remains a largely unexplored area in the field of health and practice sociology.

This paper seeks to address this intellectual and political neglect by examining the social, psychological, and legal issues that affect the lives of PWE, with a particular focus on the negotiation of arranged marriages and employment, drawing upon the analytical frameworks of sociological studies of stigma and critical race theory, as well as the cultural paradigms of health and suffering. In addition, PWE reported continued discrimination, harassment, and preconceived notions of cognitive impairment in the workplace due to the prevalence of cultural beliefs and popular depictions of seizures associated with epilepsy, reported in many reference articles [7].

Despite these advances in science, significant progress has not yet been made in the treatment of individuals with epilepsy. This confirms Wolf’s assertion that epilepsy is a phenomenon that exists in two distinct realms: The realm of scientific progress in epilepsy treatment, where considerable progress has been made, and the realm of religious belief and prejudice, which has remained relatively resilient despite the numerous initiatives taken by PWE [8, 9]. Stigma and the resulting psychosocial problems are enormous obstacles that PWE face every day. Women with epilepsy, especially in poor countries, are often ill-equipped to deal with the stigma that they face on many levels. This article searched sociology and social psychology on stigma and how it can lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination about epilepsy or similar illnesses [10].

Materials and Methods

A quantitative research approach, utilizing structured closed and open-ended questionnaires and a thorough review of existing literature, was employed to assess epilepsy knowledge among the urban population in India. Of the 418 individuals approached, 401 participated in the study, and their responses were analyzed statistically. A questionnaire was formulated and sent through an e-platform (Google form) to seek responses about epilepsy. The questionnaire included close-ended and open-ended questions to gather information and examine the attitudes and behaviour regarding epilepsy.

Since the e-platform provides access to different geographies and various sections of our society.

Most questions were Yes/No and others were standard short answer questions. The participants were provided with a brief introduction to the questionnaire to ensure that they took part in the survey voluntarily after understanding its purposes. Completing the questionnaire took about a week and a half.

The survey questionnaire was spread across the urban areas of India. While approaching 418 people, only 401 responses were considered for final statistical analysis.

Results

The respondents of this study were mostly from Gujarat, Maharashtra, UP, J&K, and Himachal Pradesh. Their socio-economic conditions were in the middle and upper-middle classes of our society. Their education level was at least that of university graduates.

Education level of responders:

● Graduate: 289

● School level: 112

● Never attended school: 0

● Work status of responders:

● Salaried: 348

● Self-employed: 53

● Non-working: 0

All respondents were professionals.

As depicted in Figure 1, awareness in the well-educated urban Indian population was 96%. This is compelling that epilepsy is more prevalent than reported in various platforms and research articles. All respondents were professionals.

While some demonstrate an adequate understanding of epilepsy, others still harbour misconceptions and erroneous beliefs. Factors, such as socioeconomic status, education level, cultural influences, and access to accurate information may influence these variations in understanding. 26% of responders said that epilepsy is contagious, the prevalence of epilepsy among responders was 56%, 31% still resort to sorcery, 38% think that an epileptic person cannot get married, and 10% believe that letting a patient during seizures smell socks or onion will help instead to seek proper medical treatment.

The respondents knew that PWE lived in their families or neighbourhood, and the prevalence was as high as 56%. This means that in rural India, the prevalence of epilepsy is sure to be higher than reported.

In the 21st century, 26% of respondents consider epilepsy contagious, and another 20% have no idea about the disease, as mentioned in Figure 2, which is itself compelling that epilepsy awareness should be aggressively pursued so that PWE can live with a better quality.

It was evident that 44% of respondents did not know which specialist doctor could treat epilepsy, as mentioned in Table 1.

.PNG)

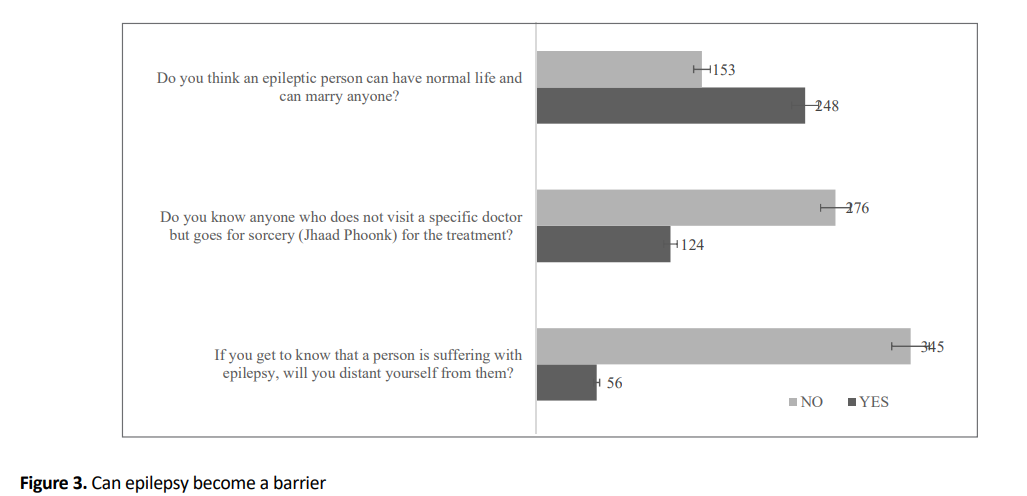

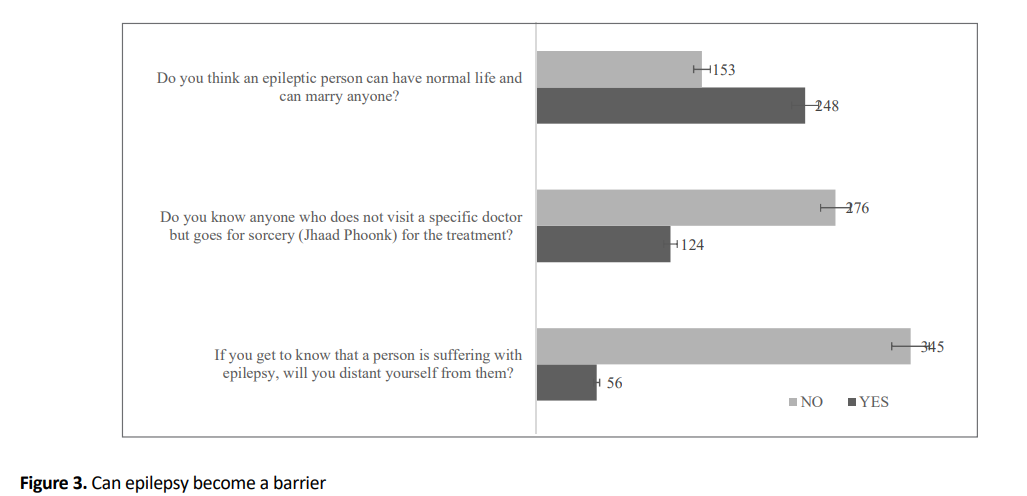

The people’s perception that PWE can have a regular daily routine is 38% of the perception that PWE cannot have a regular daily routine, as mentioned in Figure 3. It is the healthcare services’ failure to define the proper image of epilepsy that disappoints patients more.

Despite the improvement of educational and social conditions over time, the stigma, discrimination, and perception of epilepsy in the country have not changed significantly.

It is sad and compelling that epileptic patients in India face discrimination, which is depicted in Figure 3, wherein 14% of respondents said that they would distance themselves from PWE the moment they get to know it. Furthermore, the vast disparity in treatment and the lack of QoL associated with epilepsy is exacerbated by the presence of co-morbid conditions.

In Figure 3, it is pretty evident that 31% of well-educated people still think that sorcery is the option for epilepsy because they perceive it not a disease but a curse on the person with seizures.

In Table 2, it is very clear that we are far behind in creating awareness about epilepsy in common Indian. Even in urban people, the concept of epilepsy is still unclear as to what to do if a person has a seizure; 40 out of 418 respondents said they would let the person smell shoes, onion, or socks instead of helping the person to get the medical treatment.

.PNG)

In Figure 3, the public perception is still that 38% of respondents believed an epileptic person cannot get married and can live an everyday life. This strong belief has to wane-off, which is possible only by creating more awareness programmes about epilepsy. More roadshows and parodies can help familiar Indians to understand what epilepsy is and which can be managed well so people can live a normal life [11].

Discussion

This study showed how cultural belief systems and misconceptions govern society’s attitudes toward PWE in India. In this perspective, attention was paid to cultural models of illness and suffering to guide our understanding of the meaning-making process around a condition that remains stigmatised and underdiagnosed. Using online survey data revealed the interpersonal stigma experienced by PWE, particularly in marriage and the labour market. The brief review of the legal framework also sheds light on some laws governing civil rights (for example, obtaining employment) that are based on unscientific claims and prejudices that reproduce the stigma associated with epilepsy. The results of the online survey found that people with limited knowledge about epilepsy or no personal contact with someone with epilepsy reported a more negative attitude toward the condition and its treatment. This observation has been consistently demonstrated in previous studies [12]. In addition, the extent of negative attitudes is complicated by the presence of misconceptions about epilepsy as a form of dementia, considered incurable, contagious, hereditary, a form of learning and cognitive disability. Thus, by previous studies [13], the respondents note that negative stereotypes promote the concealment of the condition, which reinforces internal stigma. Social rejection anxiety resulting from this condition was exacerbated in PWE participants. Many suggest living alone (avoiding significant company) as a coping strategy to avoid social embarrassment and discomfort. We believe that this perception of women is the result of patriarchal ideologies that limit women’s freedom (more than men) to seek a job or a partner of their choice.

Even though the population is relatively well-informed about the causes and treatments of epilepsy, a high prevalence of misconceptions and myths was reported here.

With this in mind, it is essential to collect more data on the patient’s perception of the underlying causes of epilepsy and help-seeking behaviours in the Indian population. This study was conducted to gain insight into the patients’ and their families’ perception of the disease and support-seeking behaviours in an outpatient department and an indoor setting in a tertiary care hospital (TCH) in India [14-16].

Epilepsy care should include social education and public education about the disease, as well as a reasonable prescription of anti-epileptic medications. Social discrimination against PWE is primarily based on misperceptions about the disease, combined with fear and apprehension of the public on facing a seizure [17]. The misconceptions people have about epilepsy can negatively impact their health, the health of their babies and children, their hygiene, their health care needs, and their ability to accept treatment. This can lead to a low QoL for PWE. Unfortunately, no qualitative research has been found on how people feel about epilepsy in India. However, some quantitative surveys have been conducted with school kids, people in the community, and PWE. The support of caregivers and family members is crucial for compliance and better patient care [18].

The prevalence of good knowledge of epilepsy is reflected in the proportion of people who cited neurological disease or brain disease as the cause question and in the proportion of people who reported medical treatment with follow-up. However, the prevalence of myths or misconceptions was reflected in the number of people who chose possession by demons/evil spirits, envy/evil eye, or spiritual rituals/religious healing as the best treatment for epilepsy.

Despite limitations, this study tries to highlight the social, psychological, and understanding challenges that must be addressed to help improve the QoL of PWE in a context where knowledge of this condition is limited and biased. The study reveals that a person with epilepsy is caught in interconnected axes of disadvantage that limit economic and non-economic opportunities (love, society, and well-being). We argue that unless positive socio-legal interventions are directed at improving awareness and social preparation, the PWE’s lives are doomed to be entangled in shame and embarrassment for a condition over which they have no control. Our study highlighted the importance of recognizing cultural variations in understanding a neurological condition.

Conclusion

Many attempts have been made to raise awareness about epilepsy. Still, more innovative methods and tools are needed to help the public understand that epilepsy is treatable and, in most cases, it is curable with the drugs that are currently on the market. In many cases, a patient can live a seizure-free life with a higher QoL. Because this sample size is too small for the survey, the actual epilepsy awareness could be different. Therefore, a more extensive survey is needed to better understand the fundamental understanding of this life-changing disorder, specifically in rural India.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

References

India is one of the most diverse and populous countries in the world, where people of different beliefs live in different parts of the country, and it is difficult to impress the common Indians with disease awareness and its impact on society. Epilepsy is a severe brain disorder that affects 1% of the world’s population and has a significant impact on people’s quality of life (QoL), especially those with wholly controlled seizures [1].

Epilepsy has multiple causes and is multifactorial. It occurs when clusters of nerves in the brain send out abnormal signals to the rest of the brain. Anything that disrupts the typical patterns of nerve activity, from disease to brain injury to abnormal brain growth, can cause seizures [2].

Most people in our societies consider neurological disorders as taboo in India. We do not want to talk about them, and people do not understand how sensitive it is. The patient used to say, “Epilepsy cannot happen to me.” Like all of us here, the patient denied it. According to reported cases in India, nearly one-sixth of the people with epilepsy (PWE) worldwide live in India. A person with epilepsy may develop epilepsy due to abnormal wiring in the brain, an imbalance in nerve signaling chemicals known as neurotransmitters in the brain, changes in essential features of the brain’s membrane receptors and channels, or a combination of those and other factors.

India is one of the largest South Asian countries, with a population of over 1.3 billion people belonging to various castes and creeds, with various social and cultural backgrounds, and socio-economic classes. In India, people have different opinions, beliefs, perceptions, and knowledge about various situations.

One of the main issues we face in this article is the awareness, knowledge, and belief about epilepsy. Epilepsy is a chronic, non-infectious brain disease. It is characterized by repeated seizures, sometimes resulting in unconsciousness and involuntary movement of the bowel and bladder. Epilepsy can be treated with medication or surgery [3, 4].

World Health Organisation (WHO) recently reported that 80% of epileptic patients live in low and middle-class countries. Epilepsy is not contagious. While many underlying disease mechanisms can cause epilepsy, the underlying cause of epilepsy is still unknown in approximately 50% of cases worldwide. Still, 12% of the surveyed urban population believed that epilepsy does not originate from the brain, as shown in Figure 1.

.PNG)

Epilepsy causes can be classified into structural, genuine, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown. Some common causes of epilepsy include:

● Brain damage from prenatal and perinatal conditions (e.g. oxygen deprivation or trauma during birth, low birth weight)

● Congenital abnormality or genetic conditions with brain malformations

● Severe head injury

● Stroke that limits the oxygen to the brain

● Infection of the brain (including meningitis and encephalitis, specific genetic syndromes)

● Brain tumour

According to some estimates, as many as 70% of PWE could live seizure-free if diagnosed and treated correctly [5].

This issue suggests that more exhaustive studies should be conducted to assess the actual prevalence of epilepsy in India.

Epilepsy is one of the most common medical conditions in that PWE do not seek treatment from a professional. Some of the reasons why people do not seek treatment for epilepsy are:

● People have negative attitudes towards the help available.

● People are concerned about the cost of treatment.

● People are worried about transportation or inconvenience.

● People are afraid of breach of confidentiality.

● People feel like they can manage the problem alone.

● Traditional healers are one of the leading providers of treatment for epilepsy in India.

● People who believe in the supernatural cause of epilepsy mainly seek treatment from indigenous healers in India.

● Many people do not receive epilepsy treatment due to delay in initiation.

● Many people in the community do not receive treatment for epilepsy.

The myths and misunderstandings about epilepsy also affect the patient’s health. For example, due to the belief in superstitions and supernatural powers, patients are often forced to rely on religious healing and traditional treatments that can damage their health [6].

Epilepsy has a detrimental impact on educational attainment, employment, marital status, and other fundamental social relationships. The economic burden of epilepsy is exceptionally high, with the cost of treatment and travel is a significant factor. This culminates in a vicious cycle of economic burden and inadequate disease outcomes [6]. Public awareness campaigns and allocated disease days should be implemented because they play a vital role in eliminating the stigma and misperceptions associated with epilepsy.

In the Indian urban population, only 52% knew that medications are available that can well manage the epilepsy condition and that PWE can live a seizure-free life, and 48% believed that medications are unavailable that can help a person with epilepsy live seizure-free life, as shown in Figure 2.

.PNG)

It is remarkable that, even though approximately 12 million individuals in India are affected by epilepsy, this remains a largely unexplored area in the field of health and practice sociology.

This paper seeks to address this intellectual and political neglect by examining the social, psychological, and legal issues that affect the lives of PWE, with a particular focus on the negotiation of arranged marriages and employment, drawing upon the analytical frameworks of sociological studies of stigma and critical race theory, as well as the cultural paradigms of health and suffering. In addition, PWE reported continued discrimination, harassment, and preconceived notions of cognitive impairment in the workplace due to the prevalence of cultural beliefs and popular depictions of seizures associated with epilepsy, reported in many reference articles [7].

Despite these advances in science, significant progress has not yet been made in the treatment of individuals with epilepsy. This confirms Wolf’s assertion that epilepsy is a phenomenon that exists in two distinct realms: The realm of scientific progress in epilepsy treatment, where considerable progress has been made, and the realm of religious belief and prejudice, which has remained relatively resilient despite the numerous initiatives taken by PWE [8, 9]. Stigma and the resulting psychosocial problems are enormous obstacles that PWE face every day. Women with epilepsy, especially in poor countries, are often ill-equipped to deal with the stigma that they face on many levels. This article searched sociology and social psychology on stigma and how it can lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination about epilepsy or similar illnesses [10].

Materials and Methods

A quantitative research approach, utilizing structured closed and open-ended questionnaires and a thorough review of existing literature, was employed to assess epilepsy knowledge among the urban population in India. Of the 418 individuals approached, 401 participated in the study, and their responses were analyzed statistically. A questionnaire was formulated and sent through an e-platform (Google form) to seek responses about epilepsy. The questionnaire included close-ended and open-ended questions to gather information and examine the attitudes and behaviour regarding epilepsy.

Since the e-platform provides access to different geographies and various sections of our society.

Most questions were Yes/No and others were standard short answer questions. The participants were provided with a brief introduction to the questionnaire to ensure that they took part in the survey voluntarily after understanding its purposes. Completing the questionnaire took about a week and a half.

The survey questionnaire was spread across the urban areas of India. While approaching 418 people, only 401 responses were considered for final statistical analysis.

Results

The respondents of this study were mostly from Gujarat, Maharashtra, UP, J&K, and Himachal Pradesh. Their socio-economic conditions were in the middle and upper-middle classes of our society. Their education level was at least that of university graduates.

Education level of responders:

● Graduate: 289

● School level: 112

● Never attended school: 0

● Work status of responders:

● Salaried: 348

● Self-employed: 53

● Non-working: 0

All respondents were professionals.

As depicted in Figure 1, awareness in the well-educated urban Indian population was 96%. This is compelling that epilepsy is more prevalent than reported in various platforms and research articles. All respondents were professionals.

While some demonstrate an adequate understanding of epilepsy, others still harbour misconceptions and erroneous beliefs. Factors, such as socioeconomic status, education level, cultural influences, and access to accurate information may influence these variations in understanding. 26% of responders said that epilepsy is contagious, the prevalence of epilepsy among responders was 56%, 31% still resort to sorcery, 38% think that an epileptic person cannot get married, and 10% believe that letting a patient during seizures smell socks or onion will help instead to seek proper medical treatment.

The respondents knew that PWE lived in their families or neighbourhood, and the prevalence was as high as 56%. This means that in rural India, the prevalence of epilepsy is sure to be higher than reported.

In the 21st century, 26% of respondents consider epilepsy contagious, and another 20% have no idea about the disease, as mentioned in Figure 2, which is itself compelling that epilepsy awareness should be aggressively pursued so that PWE can live with a better quality.

It was evident that 44% of respondents did not know which specialist doctor could treat epilepsy, as mentioned in Table 1.

.PNG)

The people’s perception that PWE can have a regular daily routine is 38% of the perception that PWE cannot have a regular daily routine, as mentioned in Figure 3. It is the healthcare services’ failure to define the proper image of epilepsy that disappoints patients more.

Despite the improvement of educational and social conditions over time, the stigma, discrimination, and perception of epilepsy in the country have not changed significantly.

It is sad and compelling that epileptic patients in India face discrimination, which is depicted in Figure 3, wherein 14% of respondents said that they would distance themselves from PWE the moment they get to know it. Furthermore, the vast disparity in treatment and the lack of QoL associated with epilepsy is exacerbated by the presence of co-morbid conditions.

In Figure 3, it is pretty evident that 31% of well-educated people still think that sorcery is the option for epilepsy because they perceive it not a disease but a curse on the person with seizures.

In Table 2, it is very clear that we are far behind in creating awareness about epilepsy in common Indian. Even in urban people, the concept of epilepsy is still unclear as to what to do if a person has a seizure; 40 out of 418 respondents said they would let the person smell shoes, onion, or socks instead of helping the person to get the medical treatment.

.PNG)

In Figure 3, the public perception is still that 38% of respondents believed an epileptic person cannot get married and can live an everyday life. This strong belief has to wane-off, which is possible only by creating more awareness programmes about epilepsy. More roadshows and parodies can help familiar Indians to understand what epilepsy is and which can be managed well so people can live a normal life [11].

Discussion

This study showed how cultural belief systems and misconceptions govern society’s attitudes toward PWE in India. In this perspective, attention was paid to cultural models of illness and suffering to guide our understanding of the meaning-making process around a condition that remains stigmatised and underdiagnosed. Using online survey data revealed the interpersonal stigma experienced by PWE, particularly in marriage and the labour market. The brief review of the legal framework also sheds light on some laws governing civil rights (for example, obtaining employment) that are based on unscientific claims and prejudices that reproduce the stigma associated with epilepsy. The results of the online survey found that people with limited knowledge about epilepsy or no personal contact with someone with epilepsy reported a more negative attitude toward the condition and its treatment. This observation has been consistently demonstrated in previous studies [12]. In addition, the extent of negative attitudes is complicated by the presence of misconceptions about epilepsy as a form of dementia, considered incurable, contagious, hereditary, a form of learning and cognitive disability. Thus, by previous studies [13], the respondents note that negative stereotypes promote the concealment of the condition, which reinforces internal stigma. Social rejection anxiety resulting from this condition was exacerbated in PWE participants. Many suggest living alone (avoiding significant company) as a coping strategy to avoid social embarrassment and discomfort. We believe that this perception of women is the result of patriarchal ideologies that limit women’s freedom (more than men) to seek a job or a partner of their choice.

Even though the population is relatively well-informed about the causes and treatments of epilepsy, a high prevalence of misconceptions and myths was reported here.

With this in mind, it is essential to collect more data on the patient’s perception of the underlying causes of epilepsy and help-seeking behaviours in the Indian population. This study was conducted to gain insight into the patients’ and their families’ perception of the disease and support-seeking behaviours in an outpatient department and an indoor setting in a tertiary care hospital (TCH) in India [14-16].

Epilepsy care should include social education and public education about the disease, as well as a reasonable prescription of anti-epileptic medications. Social discrimination against PWE is primarily based on misperceptions about the disease, combined with fear and apprehension of the public on facing a seizure [17]. The misconceptions people have about epilepsy can negatively impact their health, the health of their babies and children, their hygiene, their health care needs, and their ability to accept treatment. This can lead to a low QoL for PWE. Unfortunately, no qualitative research has been found on how people feel about epilepsy in India. However, some quantitative surveys have been conducted with school kids, people in the community, and PWE. The support of caregivers and family members is crucial for compliance and better patient care [18].

The prevalence of good knowledge of epilepsy is reflected in the proportion of people who cited neurological disease or brain disease as the cause question and in the proportion of people who reported medical treatment with follow-up. However, the prevalence of myths or misconceptions was reflected in the number of people who chose possession by demons/evil spirits, envy/evil eye, or spiritual rituals/religious healing as the best treatment for epilepsy.

Despite limitations, this study tries to highlight the social, psychological, and understanding challenges that must be addressed to help improve the QoL of PWE in a context where knowledge of this condition is limited and biased. The study reveals that a person with epilepsy is caught in interconnected axes of disadvantage that limit economic and non-economic opportunities (love, society, and well-being). We argue that unless positive socio-legal interventions are directed at improving awareness and social preparation, the PWE’s lives are doomed to be entangled in shame and embarrassment for a condition over which they have no control. Our study highlighted the importance of recognizing cultural variations in understanding a neurological condition.

Conclusion

Many attempts have been made to raise awareness about epilepsy. Still, more innovative methods and tools are needed to help the public understand that epilepsy is treatable and, in most cases, it is curable with the drugs that are currently on the market. In many cases, a patient can live a seizure-free life with a higher QoL. Because this sample size is too small for the survey, the actual epilepsy awareness could be different. Therefore, a more extensive survey is needed to better understand the fundamental understanding of this life-changing disorder, specifically in rural India.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Mehndiratta MM, Kukkuta Sarma GR, Tripathi M, Ravat S, Gopinath S, Babu S, et al. A Multicenter, cross-sectional, observational study on epilepsy and its management practices in India. Neurol India. 2022; 70(5):2031-8. [DOI:10.4103/0028-3886.359162] [PMID]

- Giourou E, Stavropoulou-Deli A, Giannakopoulou A, Kostopoulos GK, Koutroumanidis M. Introduction to epilepsy and related brain disorders. In: Voros N, Antonopoulos C, editors. Cyberphysical systems for epilepsy and related brain disorders. Cham: Springer; 2015. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-20049-1_2]

- WHO. The global burden of disease : 2004 update. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Link]

- Sawatzky R, Ratner PA, Chiu L. A Meta-Analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 2005; 72(2):153-88. [DOI:10.1007/s11205-004-5577-x]

- WHO. Epilepsy. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Link]

- Zainy LE, Atteyah DM, Aldisi WM, Abdulkarim HA, Alhelo RF, Alhelali HA, et al. Parents’ knowledge and attitudes toward children with epilepsy. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2013; 18(4):345-8. [PMID]

- Gosain K, Samanta T. Understanding the role of stigma and misconceptions in the experience of epilepsy in India: Findings from a mixed-methods study. Front Sociol. 2022; 7:790145. [DOI:10.3389/fsoc.2022.790145] [PMID]

- Thomas SV, Nair A. Confronting the stigma of epilepsy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011; 14(3):158-63. [DOI:10.4103/0972-2327.85873] [PMID]

- Wolf P. Sociocultural history of epilepsy. In: Panayiotopoulos CP, editor. Atlas of Epilepsies. London: Springer ; 2010. [Link]

- Rajesh P. Patient Education is the need of the hour, why? 2024. [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.31124/advance.172416307.75640268/v1]

- Pandita, R.; Patel, R. Impact of care gaps in epileptic patients in India-a review.2024. [Preprints] [DOI:10.20944/preprints202405.1147.v1]

- Guekht AB, Mitrokhina TV, Lebedeva AV, Dzugaeva FK, Milchakova LE, Lokshina OB, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2007; 16(2):128-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.seizure.2006.10.011] [PMID]

- Aydemir N, Kaya B, Yıldız G, Öztura I, Baklan B. Determinants of felt stigma in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016; 58:76-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.03.008] [PMID]

- Shorvon SD, Farmer PJ. Epilepsy in developing countries: A review of epidemiological, sociocultural, and treatment aspects. Epilepsia. 1988; 29(s1):S36-54. [DOI:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05790.x]

- Das G, Biswas S, Dubey S, Lahiri D, Ray BK, Pandit A, et al. Perception about etiology of epilepsy and help-seeking behavior in patients with epilepsy. Int J Epilepsy. 2021; 7(01):22-8. [DOI:10.1055/s-0041-1731933]

- Sinha A, Mallik S, Sanyal D, Sengupta P, Dasgupta S. Healthcare-seeking behavior of patients with epileptic seizure disorders attending a tertiary care hospital, Kolkata. Indian J Community Med. 2012; 37(1):25-9. [DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.94018] [PMID]

- Thacker AK, Verma AM, Ji R, Thacker P, Mishra P. Knowledge awareness and attitude about epilepsy among schoolteachers in India. Seizure. 2008; 17(8):684-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.seizure.2008.04.007] [PMID]

- Dhikale PT, Dongre AR. Perceptions of the community about epilepsy in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2017; 6(3):628-33. [DOI:10.5455/ijmsph.2017.1061014112016]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Professional education and practice

Received: 2024/10/7 | Accepted: 2024/12/8 | Published: 2024/03/8

Received: 2024/10/7 | Accepted: 2024/12/8 | Published: 2024/03/8