Volume 7, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

Func Disabil J 2024, 7(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohammadi Dehbokr S, Torabinezhad F, Ghorbani A, Mohamadi R, Kamali M, Habibi A. Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Iranian Version of the Voice Symptom Scale. Func Disabil J 2024; 7 (1) : 282.2

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-254-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-254-en.html

Siavash Mohammadi Dehbokr1

, Farhad Torabinezhad1

, Farhad Torabinezhad1

, Ali Ghorbani1

, Ali Ghorbani1

, Reyhane Mohamadi *2

, Reyhane Mohamadi *2

, Mohammad Kamali3

, Mohammad Kamali3

, Amirali Habibi1

, Amirali Habibi1

, Farhad Torabinezhad1

, Farhad Torabinezhad1

, Ali Ghorbani1

, Ali Ghorbani1

, Reyhane Mohamadi *2

, Reyhane Mohamadi *2

, Mohammad Kamali3

, Mohammad Kamali3

, Amirali Habibi1

, Amirali Habibi1

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,mohamadi.re95@gmail.com

3- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1068 kb]

(305 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1059 Views)

Discussion

Several vocal QOL instruments have been developed in recent decades [4, 6]. However, most of them are in English and cannot be used for Iranian communities due to linguistic and cultural differences [3]. Therefore, they need to be validated rigorously to adapt to both linguistic differences and cultural diversity. The current was carried out to assess the validity and cultural adoption of the Iranian version of the VoiSS. VoiSS provides information about the presence of vocal symptoms and additionally, it could be used as a useful instrument for voice evaluation, as well. Moreover, it is already proven that VoiSS has favorable psychometric properties.

The current study was performed in 3 main steps, including translation, and cultural adoption, validity and reliability study. First of all, the translation process was done and we prepared a Persian-translated format of VoiSS. In this step, no items were removed from the original questionnaire and we found no item closely about ethnical or cultural aspects leading to misinterpretation in Persian culture. In Brazilian, Italian, and Bengali versions, no items were removed and VoiSS seems to be easily adapted to different cultures [10, 12].

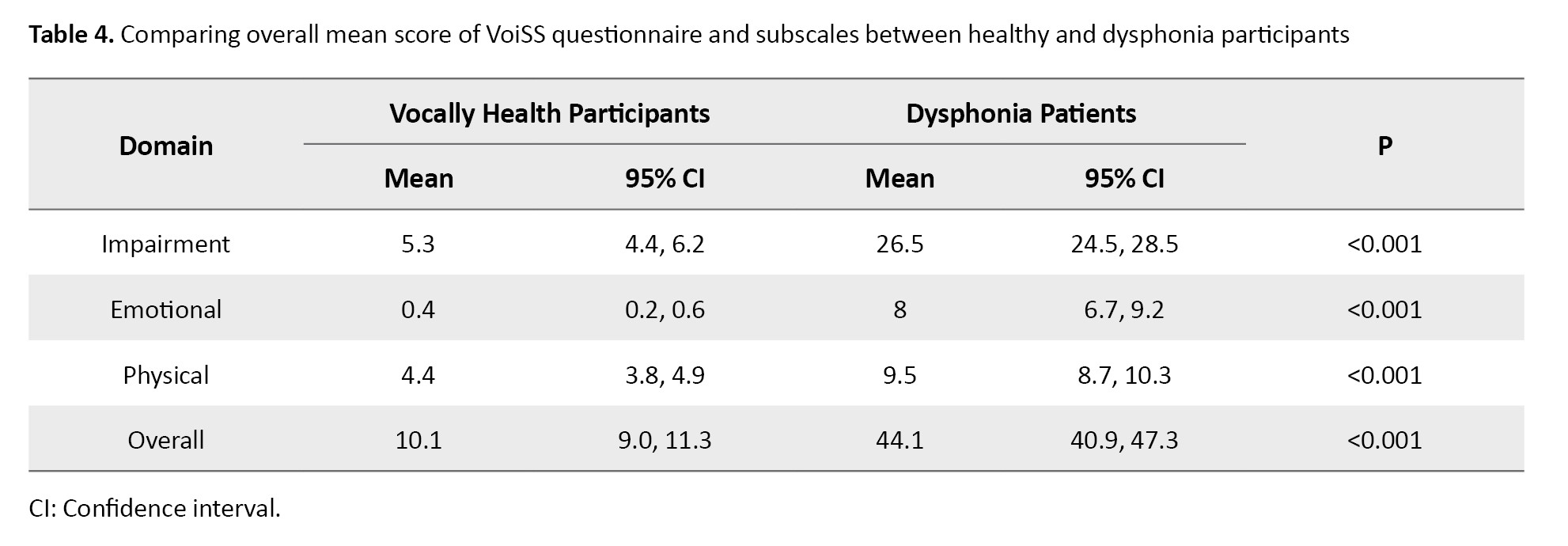

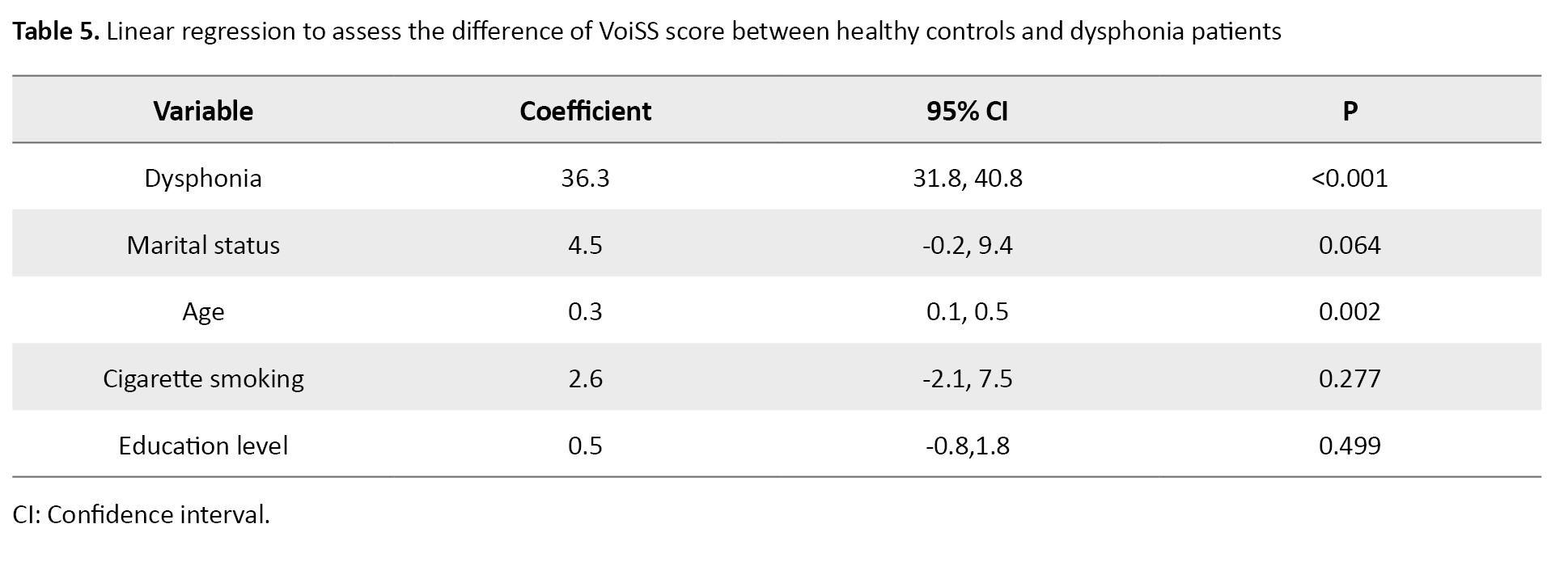

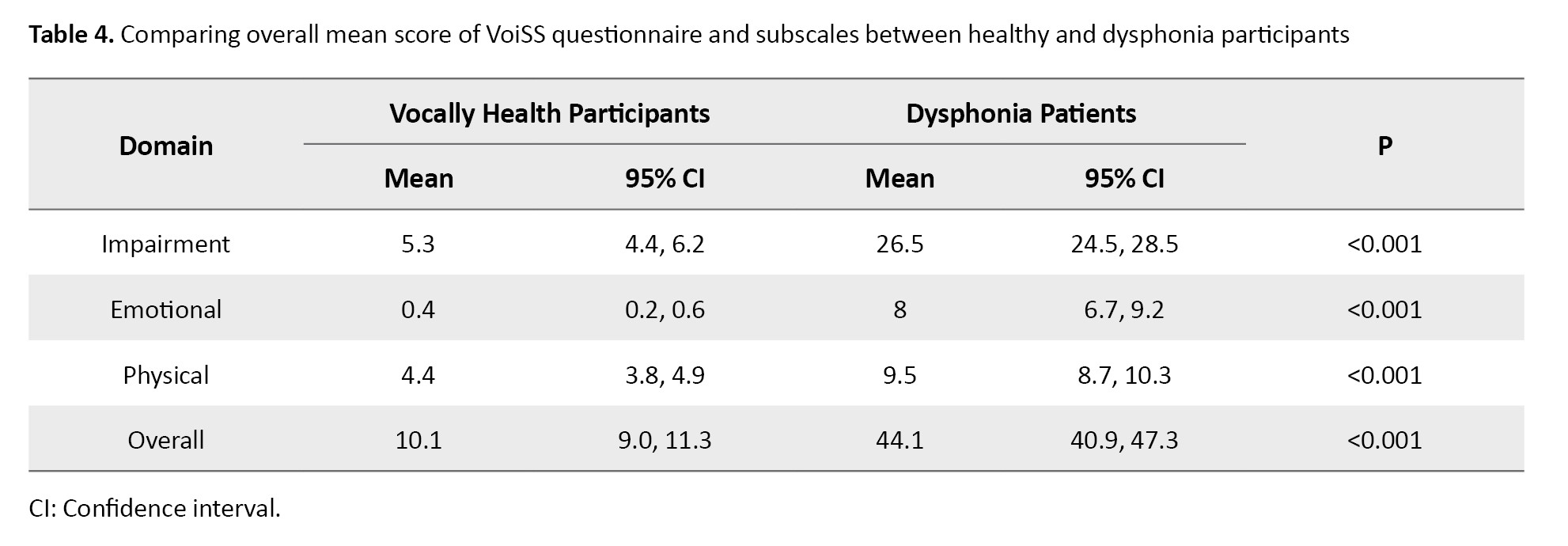

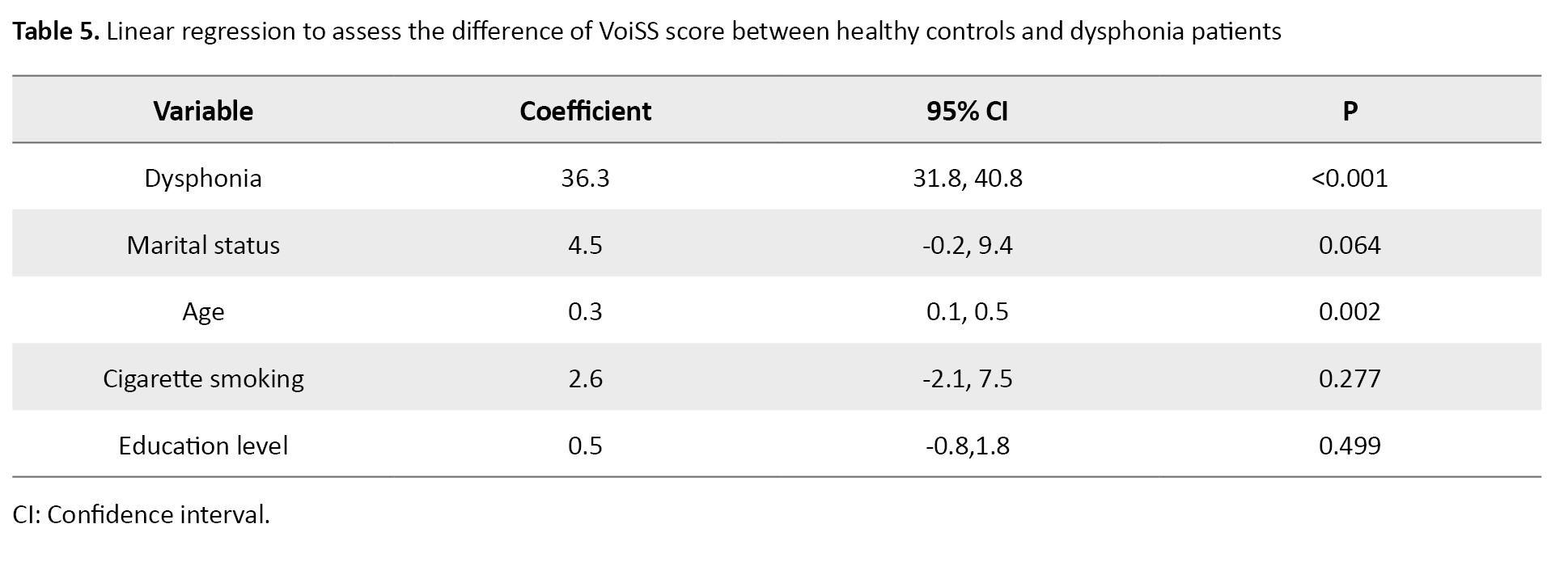

In the validity study, we compared two healthy and dysphonia groups and this study depicted that the total mean score of the VoiSS questionnaire for dysphonia patients even after adjustment for confounding variables was much higher and we observed the same difference in the questionnaire subscales. High validity has been previously reported for VoiSS and it is depicted that people with poorer voices have a higher impact of voice deviation [10, 11, 13].

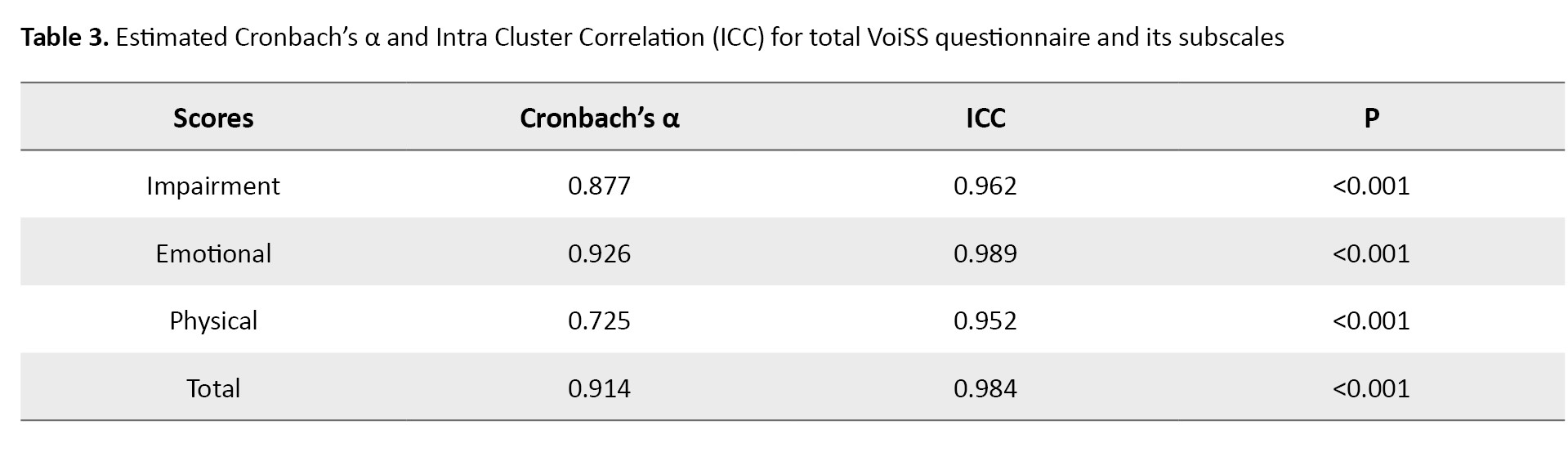

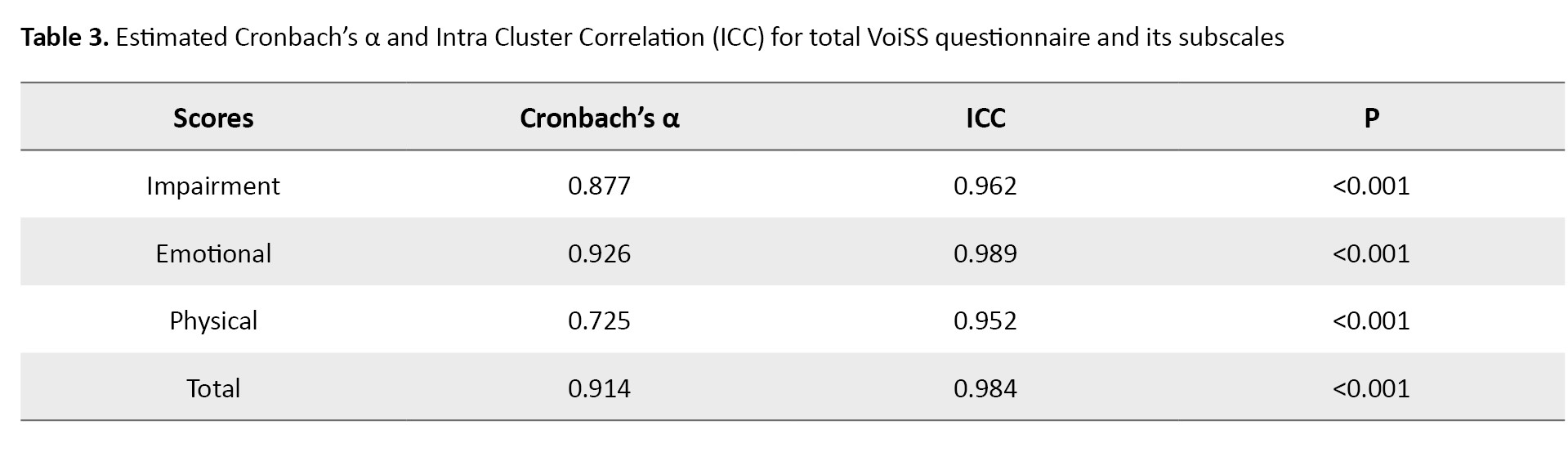

In reliability assessment, we were looking to see whether the generated results by VoiSS at the 1st time, could be repeated. For that matter, the questionnaire was administered by the same group for a short while and we analyzed the outcomes of the 1st and 2nd administrations. Both internal consistency and reproducibility assessed by Cronbach’s α and ICC were pretty high and depicted high reliability for the Persian version of VoiSS. The overall Cronbach’s α was calculated to be 0.914, which suggests a strong internal consistency for the Persian VoiSS. In previous studies in Brazil, Korea, and India high internal consistency was reported for VoiSS. We also reported high reproducibility for Persian VoiSS which was in line with previous research [11-14].

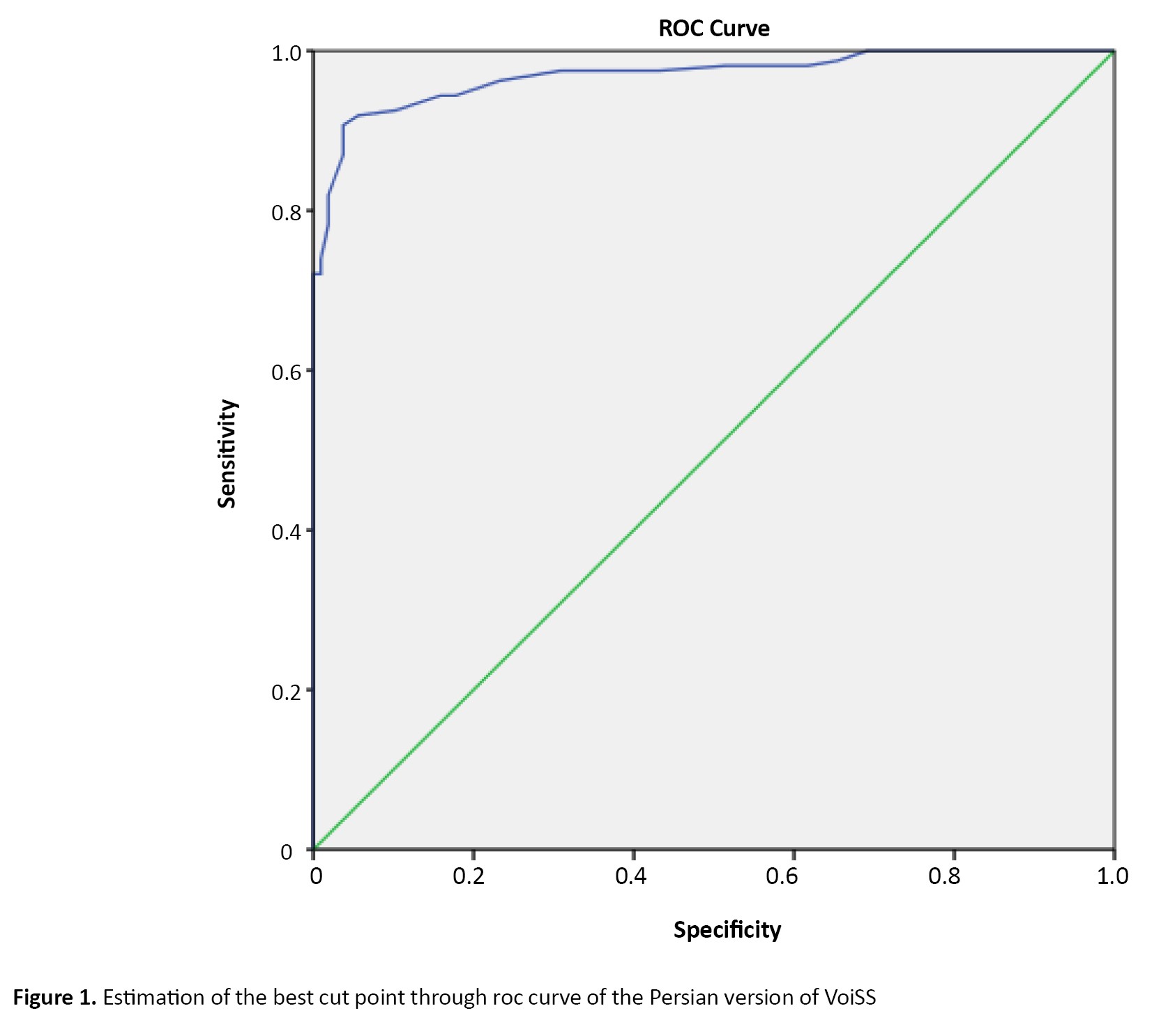

In this study, a cut-point for Persian VoiSS was estimated to use this instrument as a screening tool. The estimated sensitivity and specificity for this instrument at the best cut-point was 90.7 and 96.3 which is pretty good. Despite the high sensitivity and specificity applying VoiSS as a screening tool may lead to false positive and negative cases which are ignorable. In other publications, several different cut-points were suggested for the translated version of VoiSS, and in all studies, high accuracy is reported for VoiSS and it is regarded as a useful approach for screening [11].

Conclusion

The Persian VoiSS can be considered a valid and reliable tool to assess voice and vocal symptoms. It can be used with high accuracy in screening high-risk populations to discriminate dysphonic patients from healthy individuals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study method was approved by the deputy of research, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code:IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9211).

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master' s thesis of Siavash Mohammadi Dehbokr, approved by the Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This study was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Farhad Torabinezhad; Methodology: Mohamadd Kamali; Writing the original draft: Siavash Mohammadi Dehbokr and Amirali Habibi; Investigation, Review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to convey their appreciation to all the individuals who participated in the study.

References

Full-Text: (402 Views)

Introduction

The issue of the voice disorder’s effects on patients’ quality of life (QOL) has been addressed in recent decades. To quantify such impact and to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches, numerous self-assessment questionnaires have been developed that gather valuable information about symptoms or complaints reported by patients. Clinicians can utilize this information to assess patient’s progress and inform them of treatment choices [1, 2]. Therefore, we have to translate this questionnaire according to international guidelines, to use them in other languages [3]. Some of these well-known questionnaires include voice handicap index (VHI), voice-related QoL (V-RQOL), and voice symptom scale (VSS) [4-6]. The voice handicap index (VHI), created by Jacobson and colleagues, was the 1st questionnaire specifically designed to measure how dysphonia affects QOL, consisting of 30 items [4]. Hogikyan and Sethuraman developed the voice-related V-RQOL and has 10 items [5]. Moradi et al. translated these two questionnaires into Persian in recent years [2, 7]. But no attempt was made to translate VSS into Persian.

Wilson et al. developed the VSS questionnaire [8]. VSS is the most reliable and thoroughly validated self-assessment tool available to evaluate voice quality and was developed from 800 patients that involve the impairment, emotional, and physical symptom components, each component contains 15, 8, and 7 items respectively [6, 8, 9]. Hence, this study was conducted to translate and culturally adaptation of the original voice symptom scale (VoiSS)’ version into Persian.

Materials and Methods

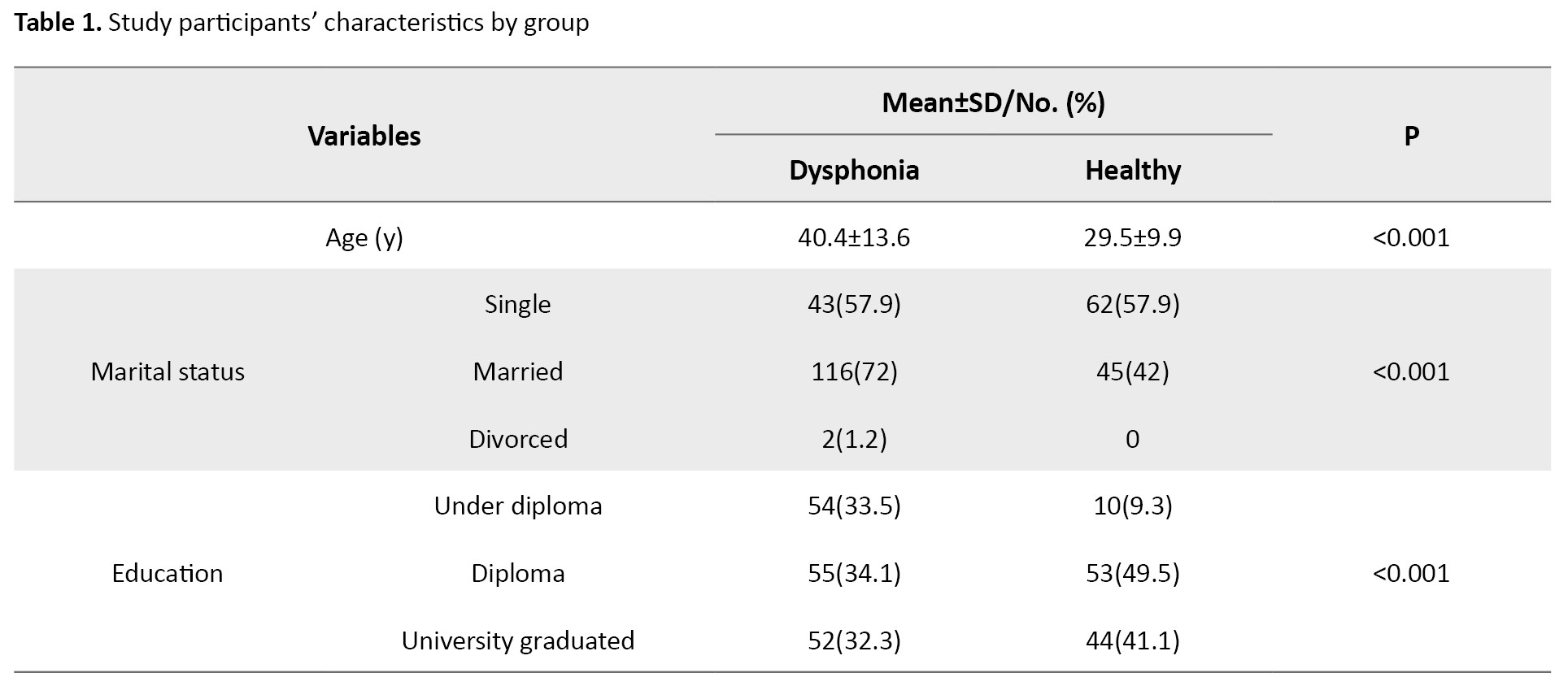

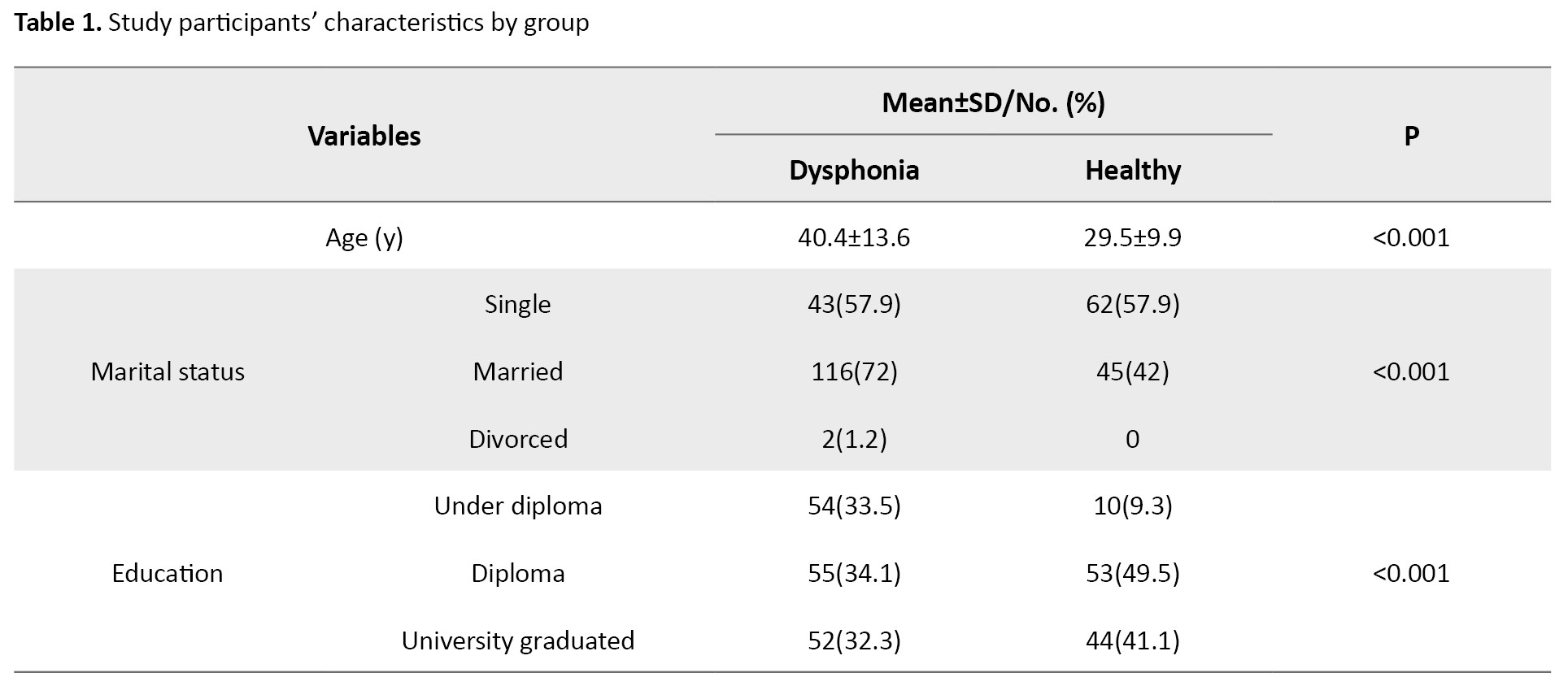

This study was conducted on a group of Iranian individuals (286 participants) diagnosed with dysphonia and a control group, to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Persian adaptation of VoiSS. Of these, 161 were dysphonic patients (101 men and 60 women) and 107 vocally healthy participants (55 men and 52 women). The Mean±SD of age for dysphonic and vocally health participation was 40.7±12.8 and 31.4±10.0, respectively. Informed was obtained from all the participants (Table 1).

Item generation

In the 1st step, two speech and language pathologists who were natively Persian translated the questionnaire into Persian. In the translation process, we insisted on simple, short, and clear wording and avoided the literal meaning of words. The translators were asked to propose any other equal or appropriate translation for each item; therefore they presented two translations for each item. The clarity of their translations is rated on a linear analog scale assessment which is a 10 cm long line and ranges from 1 to 100. On this scale, 1 is completely intelligible and 100 means completely unintelligible. Finally, we received two independent translations which were discussed by an expert panel, including five speech-language pathologists to obtain a single primary translated VoiSS questionnaire.

Then back-translation from Persian to English was carried out by two speech-language pathologists and one linguist who were natively Persian and had high proficiency in English. The back-translated form was discussed again in the expert panel in terms of conceptual equivalence with the original questionnaire. The Persian version of the VoiSS questionnaire was designed in 3 distinctive domains, including impairment (15 items), emotional (8 items), and physical (7 items).

Validity assessment

Face, content, and construct validity were used to assess the questionnaire validity we used. Qualitative content validity was conducted by an expert panel and all the required alterations were done according to the expert’s comments. For that matter, the questionnaire was completed by 20 dysphonic patients aged 19-80 years. We added two options to the response rating scale of each item, “completely intelligible” and “completely unintelligible”, so each item had seven choice point scale, never, occasionally, some of the time, most of the time, always, “completely intelligible” and “completely unintelligible”. This alteration was done to enhance questionnaire clarity and remove potential ambiguities and misunderstandings. We also decided to change the contents of the three items to enhance the clarity and conceptual equivalence of them with the original form. For example, item 6 of the original version of VSS where it says: “Do you lose your voice?”, was ambiguous for Persian speakers, hence, we added the phrase “for a while”, to equate it with the original version of VSS [6].

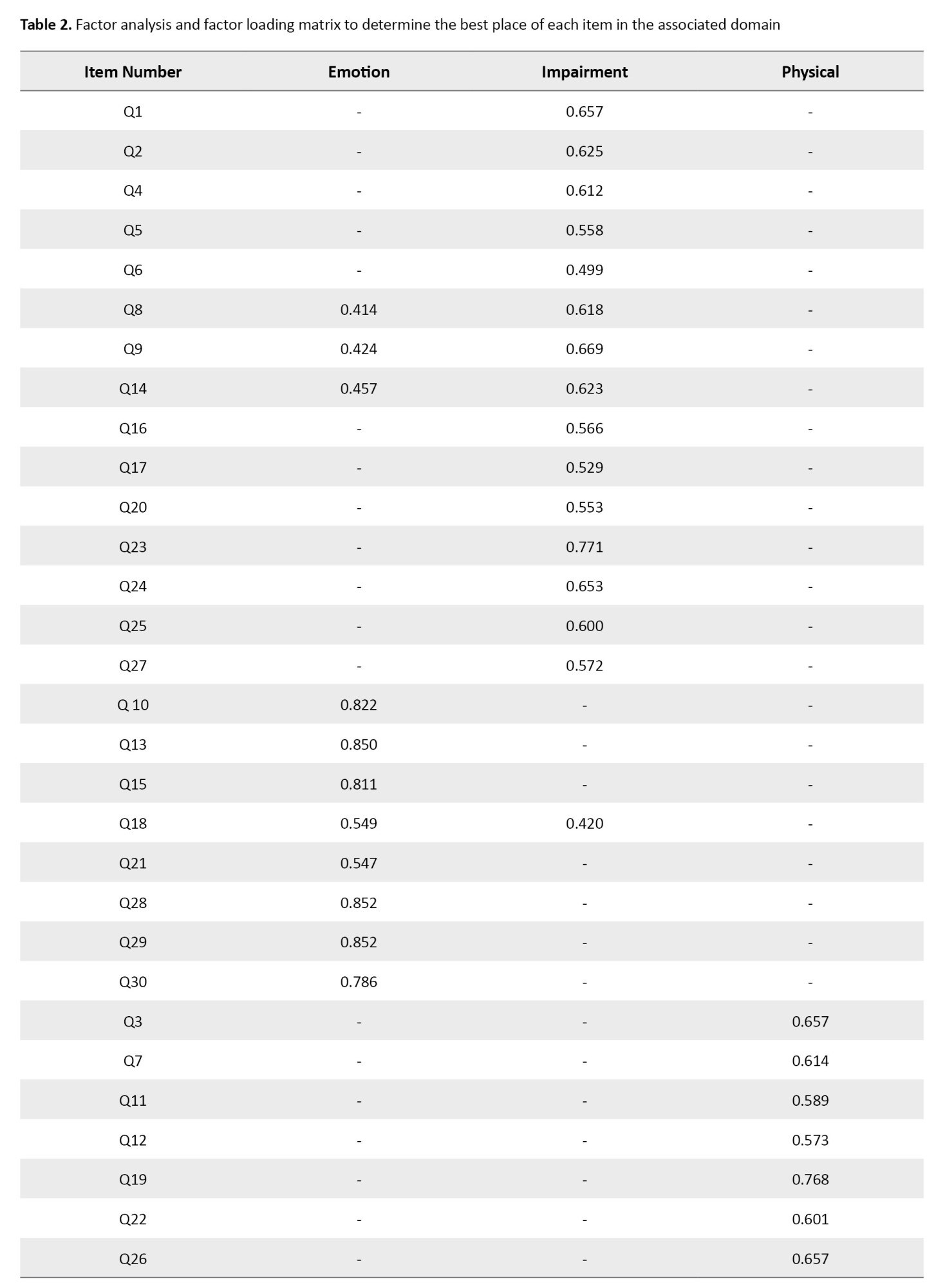

Regarding construct validity, the questionnaire was completed by 161 patients with dysphonic. The study was conducted on patients who were referred to the ear, nose, and throat Department of Rasol-Akram Hospital. Exploratory factor analysis was used to determine the best place for each item in its associated domain.

Reliability assessment

We computed Cronbach’s α for each domain to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire. We also performed test re-test analysis and in this regard, the questionnaire was given to 40 patients twice in 2 weeks. Moreover, we calculated intra-cluster correlation (ICC) for test and re-test.

Statistical analysis

We used Cronbach’s α and ICC as a measure of internal consistency and reliability. We also performed construct validity to determine the final questions of the questionnaire. Moreover, model accuracy was assessed through Bartlett’s test and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO). Furthermore, principal component extraction with varimax rotation was carried out based on factor loading to decide on the remaining questions. Factor loading values greater than 0.3 are regarded as acceptable. We also used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine the best cut point. The cut point was calculated based on the highest sensitivity and specificity. Finally, we used multiple linear regression to compare the mean score of VSS across the investigated variables. All statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software, version 19 and Liserel software.

Results

All patients and participants with healthy vocal cords involved in this study could complete the questionnaire independently. It took approximately 10 minutes to answer the questionnaire items.

Exploratory factor analysis/validity

Bartlett’s test for both dysphonia and healthy groups was statistically significant (P<0.001), while Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) for healthy and dysphonia groups was 0.452 and 0.843, respectively.

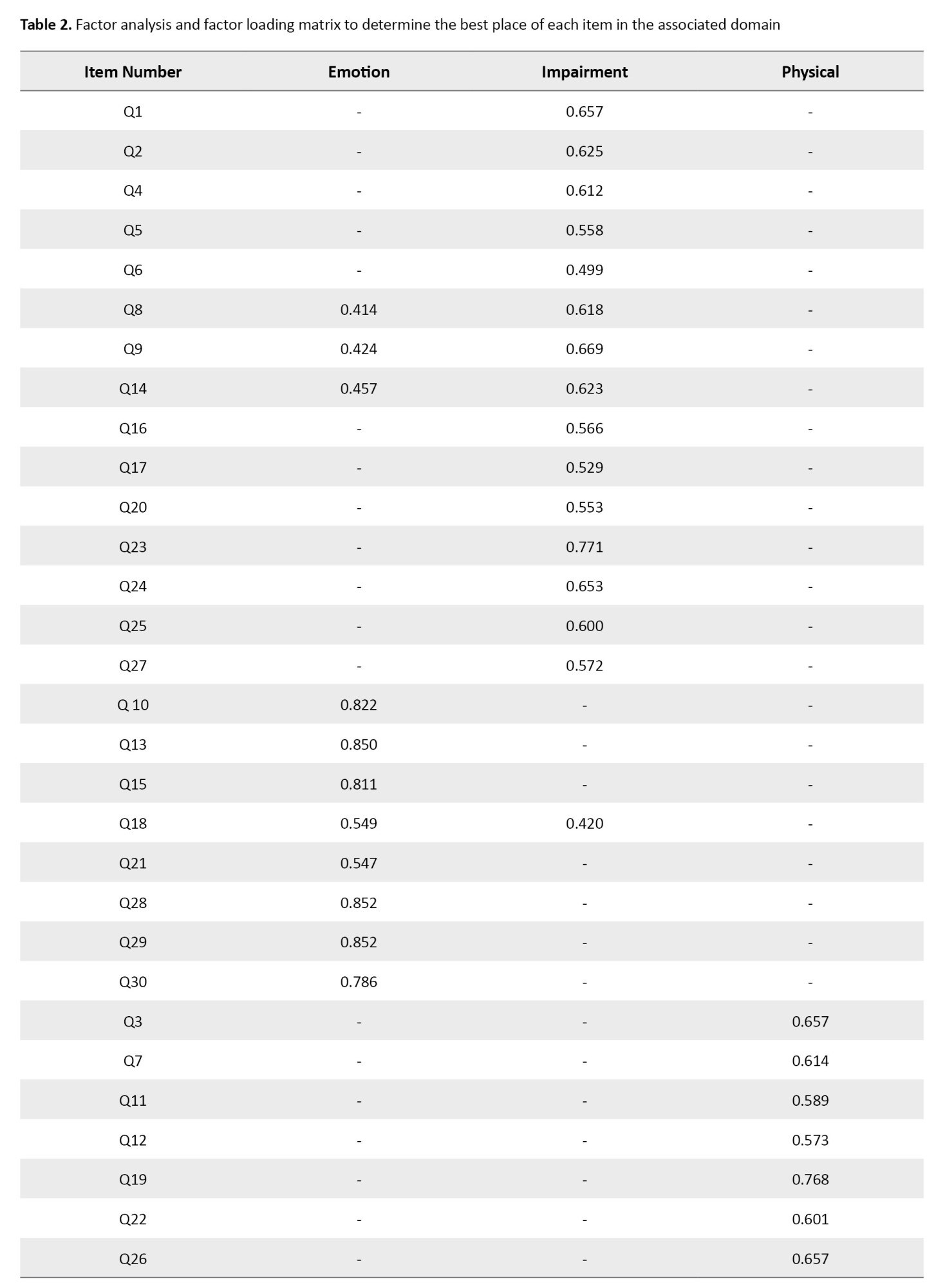

Table 2 presents the result of factor analysis and factor loadings for each item of the questionnaire.

We retained three factors explaining cumulatively 52.9% overall variance. In each factor, items with factor loading <0.4 were excluded (Table 2).

Internal consistency and reliability

Cronbach’s α was estimated at 0.914, and for impairment, emotional and physical domains, it was 0.877, 0.926, and 0.725, respectively. We also estimated ICC at 0.984 indicating high reproducibility of the Persian VoiSS questionnaire. The estimated ICC for subscale was 0.962 for impairment, 0.989 for emotional, and 0.952 for physical domains (Table 3).

The Mean±SD score of a questionnaire for the healthy group was 10.1±5.9, while it was statistically higher in dysphonia patients (44.1±20.6). We also observed statistical differences in the mean score of questionnaire subscales between healthy and dysphonia groups which is provided in Table 4.

Moreover, we assessed the difference between healthy participants and dysphonia patients in terms of the score of the VoiSS questionnaire after adjustment for confounders through multiple linear regression and observed statistical differences between comparing groups (Table 5).

Cutoff value

In this study, the cutoff value of the P-VoiSS was determined, similar to the earlier research conducted by Moreti et al. and Mozzanica et al. [10, 11]. The best cut point was estimated at 20.5 and at this point, the sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire were 90.7 and 96.3. The area under the ROC curve was also 0.970 (95% CI, 0.952%, 0.988%) (Figure 1).

The issue of the voice disorder’s effects on patients’ quality of life (QOL) has been addressed in recent decades. To quantify such impact and to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches, numerous self-assessment questionnaires have been developed that gather valuable information about symptoms or complaints reported by patients. Clinicians can utilize this information to assess patient’s progress and inform them of treatment choices [1, 2]. Therefore, we have to translate this questionnaire according to international guidelines, to use them in other languages [3]. Some of these well-known questionnaires include voice handicap index (VHI), voice-related QoL (V-RQOL), and voice symptom scale (VSS) [4-6]. The voice handicap index (VHI), created by Jacobson and colleagues, was the 1st questionnaire specifically designed to measure how dysphonia affects QOL, consisting of 30 items [4]. Hogikyan and Sethuraman developed the voice-related V-RQOL and has 10 items [5]. Moradi et al. translated these two questionnaires into Persian in recent years [2, 7]. But no attempt was made to translate VSS into Persian.

Wilson et al. developed the VSS questionnaire [8]. VSS is the most reliable and thoroughly validated self-assessment tool available to evaluate voice quality and was developed from 800 patients that involve the impairment, emotional, and physical symptom components, each component contains 15, 8, and 7 items respectively [6, 8, 9]. Hence, this study was conducted to translate and culturally adaptation of the original voice symptom scale (VoiSS)’ version into Persian.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted on a group of Iranian individuals (286 participants) diagnosed with dysphonia and a control group, to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Persian adaptation of VoiSS. Of these, 161 were dysphonic patients (101 men and 60 women) and 107 vocally healthy participants (55 men and 52 women). The Mean±SD of age for dysphonic and vocally health participation was 40.7±12.8 and 31.4±10.0, respectively. Informed was obtained from all the participants (Table 1).

Item generation

In the 1st step, two speech and language pathologists who were natively Persian translated the questionnaire into Persian. In the translation process, we insisted on simple, short, and clear wording and avoided the literal meaning of words. The translators were asked to propose any other equal or appropriate translation for each item; therefore they presented two translations for each item. The clarity of their translations is rated on a linear analog scale assessment which is a 10 cm long line and ranges from 1 to 100. On this scale, 1 is completely intelligible and 100 means completely unintelligible. Finally, we received two independent translations which were discussed by an expert panel, including five speech-language pathologists to obtain a single primary translated VoiSS questionnaire.

Then back-translation from Persian to English was carried out by two speech-language pathologists and one linguist who were natively Persian and had high proficiency in English. The back-translated form was discussed again in the expert panel in terms of conceptual equivalence with the original questionnaire. The Persian version of the VoiSS questionnaire was designed in 3 distinctive domains, including impairment (15 items), emotional (8 items), and physical (7 items).

Validity assessment

Face, content, and construct validity were used to assess the questionnaire validity we used. Qualitative content validity was conducted by an expert panel and all the required alterations were done according to the expert’s comments. For that matter, the questionnaire was completed by 20 dysphonic patients aged 19-80 years. We added two options to the response rating scale of each item, “completely intelligible” and “completely unintelligible”, so each item had seven choice point scale, never, occasionally, some of the time, most of the time, always, “completely intelligible” and “completely unintelligible”. This alteration was done to enhance questionnaire clarity and remove potential ambiguities and misunderstandings. We also decided to change the contents of the three items to enhance the clarity and conceptual equivalence of them with the original form. For example, item 6 of the original version of VSS where it says: “Do you lose your voice?”, was ambiguous for Persian speakers, hence, we added the phrase “for a while”, to equate it with the original version of VSS [6].

Regarding construct validity, the questionnaire was completed by 161 patients with dysphonic. The study was conducted on patients who were referred to the ear, nose, and throat Department of Rasol-Akram Hospital. Exploratory factor analysis was used to determine the best place for each item in its associated domain.

Reliability assessment

We computed Cronbach’s α for each domain to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire. We also performed test re-test analysis and in this regard, the questionnaire was given to 40 patients twice in 2 weeks. Moreover, we calculated intra-cluster correlation (ICC) for test and re-test.

Statistical analysis

We used Cronbach’s α and ICC as a measure of internal consistency and reliability. We also performed construct validity to determine the final questions of the questionnaire. Moreover, model accuracy was assessed through Bartlett’s test and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO). Furthermore, principal component extraction with varimax rotation was carried out based on factor loading to decide on the remaining questions. Factor loading values greater than 0.3 are regarded as acceptable. We also used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine the best cut point. The cut point was calculated based on the highest sensitivity and specificity. Finally, we used multiple linear regression to compare the mean score of VSS across the investigated variables. All statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software, version 19 and Liserel software.

Results

All patients and participants with healthy vocal cords involved in this study could complete the questionnaire independently. It took approximately 10 minutes to answer the questionnaire items.

Exploratory factor analysis/validity

Bartlett’s test for both dysphonia and healthy groups was statistically significant (P<0.001), while Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) for healthy and dysphonia groups was 0.452 and 0.843, respectively.

Table 2 presents the result of factor analysis and factor loadings for each item of the questionnaire.

We retained three factors explaining cumulatively 52.9% overall variance. In each factor, items with factor loading <0.4 were excluded (Table 2).

Internal consistency and reliability

Cronbach’s α was estimated at 0.914, and for impairment, emotional and physical domains, it was 0.877, 0.926, and 0.725, respectively. We also estimated ICC at 0.984 indicating high reproducibility of the Persian VoiSS questionnaire. The estimated ICC for subscale was 0.962 for impairment, 0.989 for emotional, and 0.952 for physical domains (Table 3).

The Mean±SD score of a questionnaire for the healthy group was 10.1±5.9, while it was statistically higher in dysphonia patients (44.1±20.6). We also observed statistical differences in the mean score of questionnaire subscales between healthy and dysphonia groups which is provided in Table 4.

Moreover, we assessed the difference between healthy participants and dysphonia patients in terms of the score of the VoiSS questionnaire after adjustment for confounders through multiple linear regression and observed statistical differences between comparing groups (Table 5).

Cutoff value

In this study, the cutoff value of the P-VoiSS was determined, similar to the earlier research conducted by Moreti et al. and Mozzanica et al. [10, 11]. The best cut point was estimated at 20.5 and at this point, the sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire were 90.7 and 96.3. The area under the ROC curve was also 0.970 (95% CI, 0.952%, 0.988%) (Figure 1).

Discussion

Several vocal QOL instruments have been developed in recent decades [4, 6]. However, most of them are in English and cannot be used for Iranian communities due to linguistic and cultural differences [3]. Therefore, they need to be validated rigorously to adapt to both linguistic differences and cultural diversity. The current was carried out to assess the validity and cultural adoption of the Iranian version of the VoiSS. VoiSS provides information about the presence of vocal symptoms and additionally, it could be used as a useful instrument for voice evaluation, as well. Moreover, it is already proven that VoiSS has favorable psychometric properties.

The current study was performed in 3 main steps, including translation, and cultural adoption, validity and reliability study. First of all, the translation process was done and we prepared a Persian-translated format of VoiSS. In this step, no items were removed from the original questionnaire and we found no item closely about ethnical or cultural aspects leading to misinterpretation in Persian culture. In Brazilian, Italian, and Bengali versions, no items were removed and VoiSS seems to be easily adapted to different cultures [10, 12].

In the validity study, we compared two healthy and dysphonia groups and this study depicted that the total mean score of the VoiSS questionnaire for dysphonia patients even after adjustment for confounding variables was much higher and we observed the same difference in the questionnaire subscales. High validity has been previously reported for VoiSS and it is depicted that people with poorer voices have a higher impact of voice deviation [10, 11, 13].

In reliability assessment, we were looking to see whether the generated results by VoiSS at the 1st time, could be repeated. For that matter, the questionnaire was administered by the same group for a short while and we analyzed the outcomes of the 1st and 2nd administrations. Both internal consistency and reproducibility assessed by Cronbach’s α and ICC were pretty high and depicted high reliability for the Persian version of VoiSS. The overall Cronbach’s α was calculated to be 0.914, which suggests a strong internal consistency for the Persian VoiSS. In previous studies in Brazil, Korea, and India high internal consistency was reported for VoiSS. We also reported high reproducibility for Persian VoiSS which was in line with previous research [11-14].

In this study, a cut-point for Persian VoiSS was estimated to use this instrument as a screening tool. The estimated sensitivity and specificity for this instrument at the best cut-point was 90.7 and 96.3 which is pretty good. Despite the high sensitivity and specificity applying VoiSS as a screening tool may lead to false positive and negative cases which are ignorable. In other publications, several different cut-points were suggested for the translated version of VoiSS, and in all studies, high accuracy is reported for VoiSS and it is regarded as a useful approach for screening [11].

Conclusion

The Persian VoiSS can be considered a valid and reliable tool to assess voice and vocal symptoms. It can be used with high accuracy in screening high-risk populations to discriminate dysphonic patients from healthy individuals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study method was approved by the deputy of research, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code:IR.IUMS.REC 1395.9211).

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master' s thesis of Siavash Mohammadi Dehbokr, approved by the Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This study was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Farhad Torabinezhad; Methodology: Mohamadd Kamali; Writing the original draft: Siavash Mohammadi Dehbokr and Amirali Habibi; Investigation, Review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to convey their appreciation to all the individuals who participated in the study.

References

- Branski RC, Cukier-Blaj S, Pusic A, Cano SJ, Klassen A, Mener D, et al. Measuring quality of life in dysphonic patients: A systematic review of content development in patient-reported outcomes measures. J Voice. 2010; 24(2):193-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2008.05.006]

- Moradi N, Pourshahbaz A, Soltani M, Javadipour S, Hashemi H, Soltaninejad N. Cross-cultural equivalence and evaluation of psychometric properties of voice handicap index into Persian. J Voice. 2013; 27(2):258. e15-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.09.006]

- Lohr KN. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):193-205. [DOI:10.1023/A:1015291021312]

- Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, Silbergleit A, Jacobson G, Benninger MS, et al. The voice handicap index (VHI) development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997; 6(3):66-70. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360.0603.66]

- Hogikyan ND, Sethuraman G. Validation of an instrument to measure voice-related quality of life (V-RQOL). J Voice. 1999;13(4):557-69. [DOI:10.1016/S0892-1997(99)80010-1]

- Wilson JA, Carding AWPN, Steen IN, MacKenzie K, Deary IJ. The Voice Symptom Scale (VoiSS) and the Vocal Handicap Index (VHI): A comparison of structure and content. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004; 29(2):169-74. [DOI:10.1111/j.0307-7772.2004.00775.x]

- Moradi N, Saki N, Aghadoost O, Nikakhlagh S, Soltani M, Derakhshandeh V, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the voice-related quality of life into persian. J Voice. 2014; 28(6):842. e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.03.013]

- Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Carding PN, MacKenzie K. VoiSS: A patient-derived Voice Symptom Scale. J Psychosom Re. 2003; 54(5):483-9. [DOI:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00469-5]

- Scott S, Robinson K, Wilson JA, Mackenzie K. Patient‐reported problems associated with dysphonia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1997; 22(1):37-40. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00855.x]

- Moreti F, Zambon F, Oliveira G, Behlau M. Cross-cultural adaptation, validation, and cutoff values of the Brazilian version of the voice symptom scale-VoiSS. J Voice. 2014; 28(4):458-68. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.11.009]

- Mozzanica F, Robotti C, Ginocchio D, Bulgheroni C, Lorusso R, Behlau M, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Italian Version of the Voice Symptom Scale (I-VoiSS). J Voice. 2017; 31(6):773. e1-. e10. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.02.001]

- Kumari A, Kumar H, Hota BP, Chatterjee I. Estimating Self Perceived Voice Handicap in Hyper functional Voice Disorders Using Bengali Transadapted VoiSS. Int J Health Sci Res. 2016;6(9): 379-88. [Link]

- Son HY, Lee CY, Kim KA, Kim S, Jeong HS, Kim JP. The Korean version of the voice symptom scale for patients with thyroid operation, and its use in a validation and reliability study. J Voice. 2018; 32(3):367-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.06.003]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Speech Therapy

Received: 2024/04/7 | Accepted: 2024/07/7 | Published: 2024/03/2

Received: 2024/04/7 | Accepted: 2024/07/7 | Published: 2024/03/2