Volume 7, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

Func Disabil J 2024, 7(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ensafi Z, Kamali M, Bahadorizadeh L, Amiri Shavaki Y. Understanding the Effect of Problems and Consequences Caused by the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Clinical Activities of Speech-language Pathologists. Func Disabil J 2024; 7 (1)

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-246-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-246-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Internal Medicine, Rasoul-e-Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,amiriyoon@yahoo.com

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Internal Medicine, Rasoul-e-Akram Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 969 kb]

(173 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (87 Views)

Full-Text: (13 Views)

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019 created critical conditions around the world that continued until 2023 [1, 2]. The virus mainly leads to respiratory tract infections in humans [3]. The rapid transmission of the virus led to significant disruptions in people’s work and daily lives [4, 5]. One of the professions affected by the pandemic was speech-language pathology.

Speech-language pathologists, due to the clinical nature of their work, often engage in face-to-face communication and are exposed to the upper airway structures of clients during procedures such as oral examinations and stroboscopy. Therefore, the risk of contracting COVID-19 in these therapists is high [6].

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is crucial, yet such equipment can hinder treatment by obscuring visual, auditory, and speech communication. For example, wearing glasses and masks reduces eye contact and facial expressions. Additionally, the pandemic led to fewer client referrals, which subsequently had financial repercussions [6, 7, 8, 9]. Despite the announcement of the end of the critical situation of the pandemic in 2023 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [10], acknowledging the challenges and impacts this disease has had on the field of speech therapy has underscored the importance of learning from the complex conditions of the pandemic. On the other hand, considering the respiratory transmission of this disease and the high prevalence of respiratory diseases in the cold seasons of the year, the experiences of therapists during this period can be invaluable for future similar situations.

Previous studies exploring the effects of the pandemic on this field through surveys do not fully capture the therapists’ experiences during these crises. Furthermore, people’s experiences of a phenomenon can vary significantly due to geographical differences and available resources [11-13]. Conducting a qualitative study can provide a deeper understanding of the consequences of this pandemic and a comprehensive insight into this phenomenon, helping professionals in this field to address deficiencies, create suitable infrastructures, and enhance future performance. Therefore, the objective of this study is to explore the challenges and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinical activities of speech-language pathologists.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted using the interpretive phenomenological analysis method. In this method, the researcher discovers the personal experience of the participants to gain a deeper understanding of the desired phenomenon [14].

Participants and sampling method

Twenty-one speech-language pathologists who were actively engaged in clinical activities either in-person or virtually during the pandemic participated in this research. Sampling was conducted purposefully using the maximum variation technique to cover all treatment environments and areas of speech disorders.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews that started with open-ended questions, such as: “Please describe your experience of clinical work during the pandemic” and “How has the pandemic changed your work?”. The interviewer used a guide to steer the discussion and address the main topics. Each interview lasted between 30 to 60 minutes and was audio-recorded with the participant’s consent.

Analysis began immediately after the first interview and proceeded concurrently with subsequent interviews up to the 21st interview. The interviews were transcribed and then coded using MAXQDA software, version 2020. The coded data were analyzed by thematic analysis method. In this method, codes are first grouped into clusters and then themes are formed. Then, the categories are refined, and specific names are assigned to each theme.

Trustworthiness

To enhance the scientific accuracy and reliability of the data, four criteria outlined by Lincoln and Goba were applied: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [15]. In order to increase the credibility of the data, the samples with the maximum variation were selected and a part of the data was provided to the participants after analysis to confirm the accuracy of the information. In order to increase the transferability, the sampling and analysis steps were carefully described so that the readers could make a correct judgment about the use of the findings in similar situations. In terms of dependability, in addition to the detailed description of all the stages of the research, in order to make it possible for the readers to follow the researcher’s decisions, the data were audited by another member of the research team. In order to increase the confirmability, the data were provided to other members of the research team to minimize researcher bias.

Results

Participants

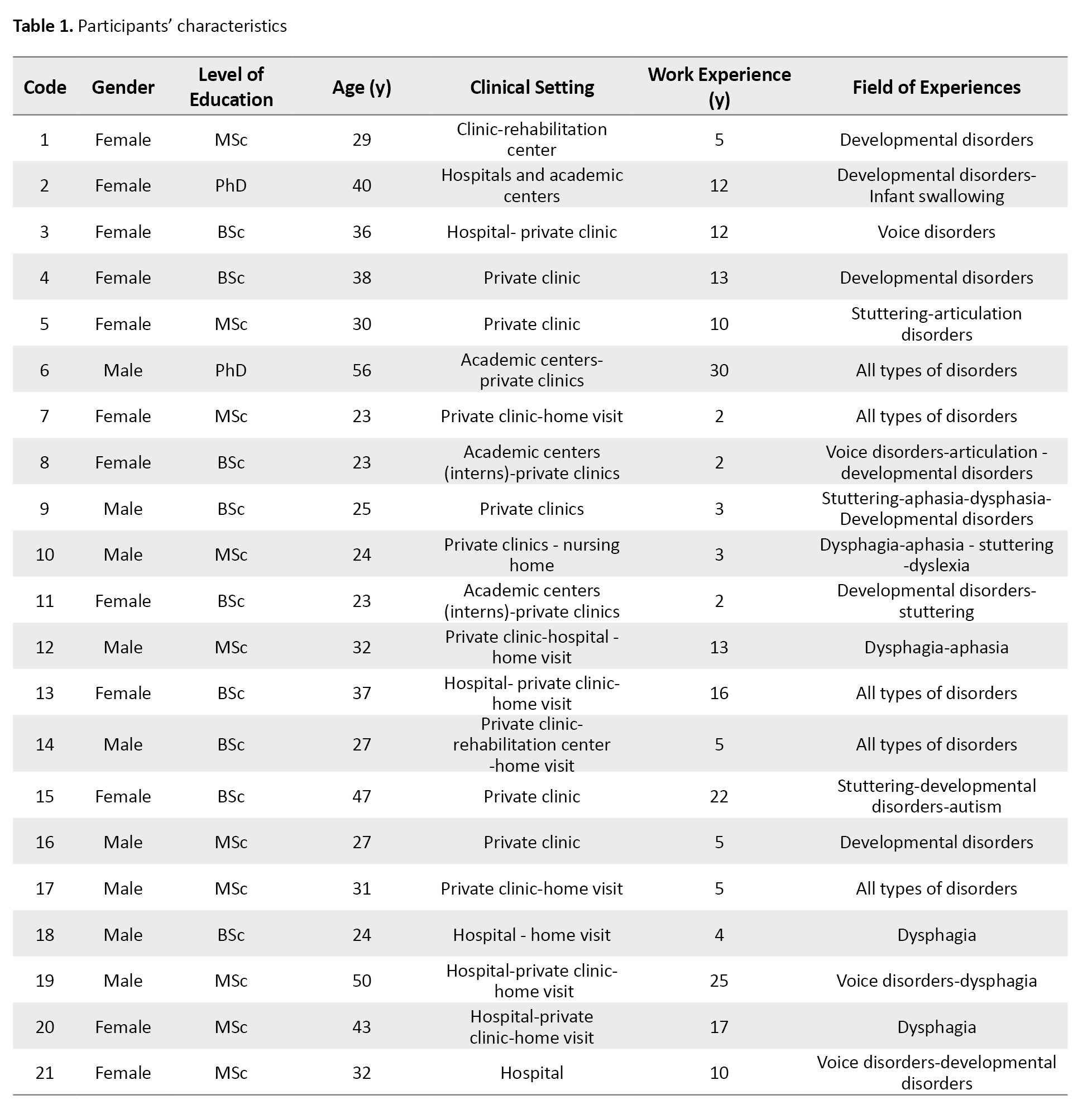

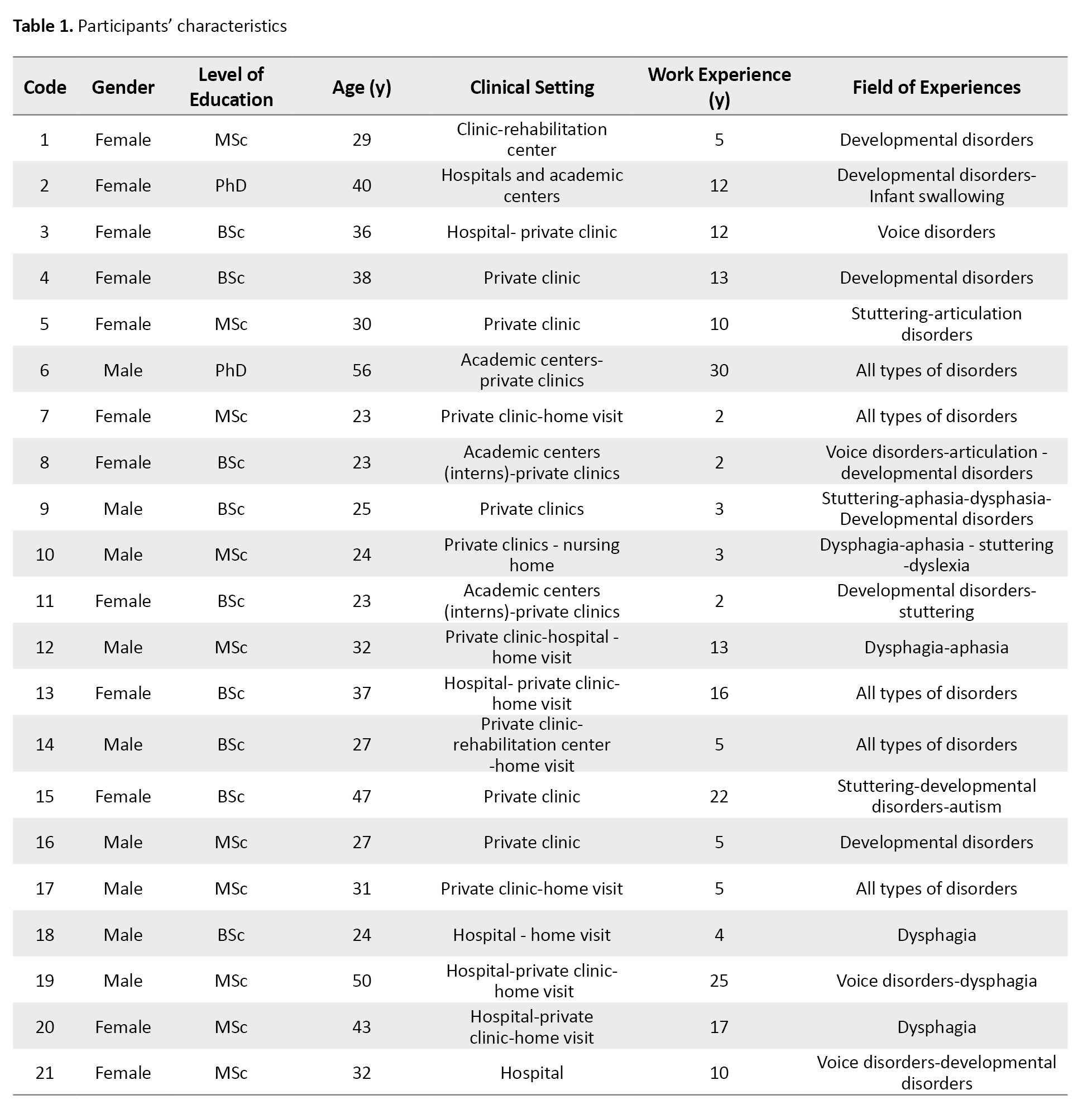

Twenty-one speech-language pathologists who conducted clinical activities both face-to-face and online during the pandemic participated in this study. The characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1.

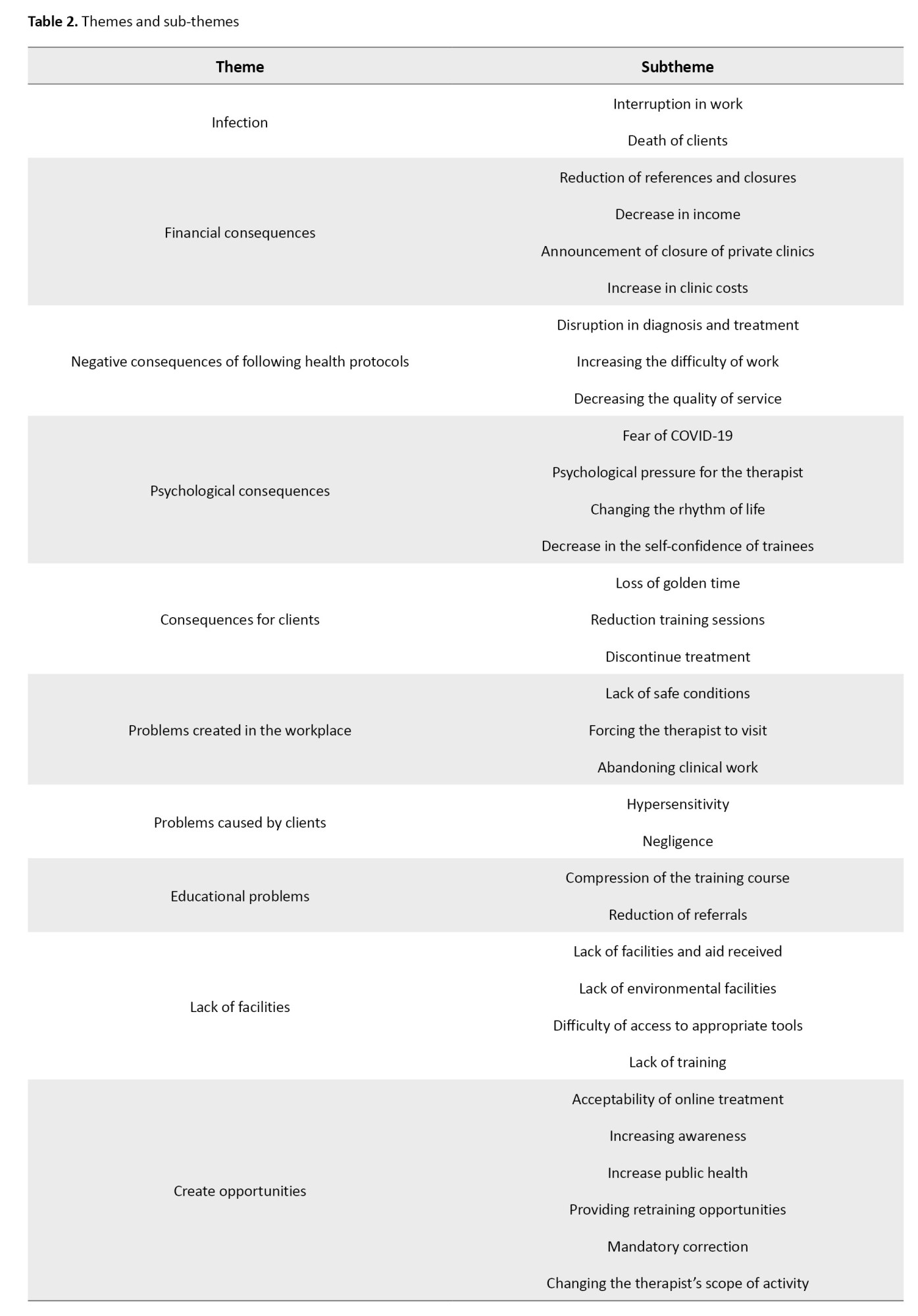

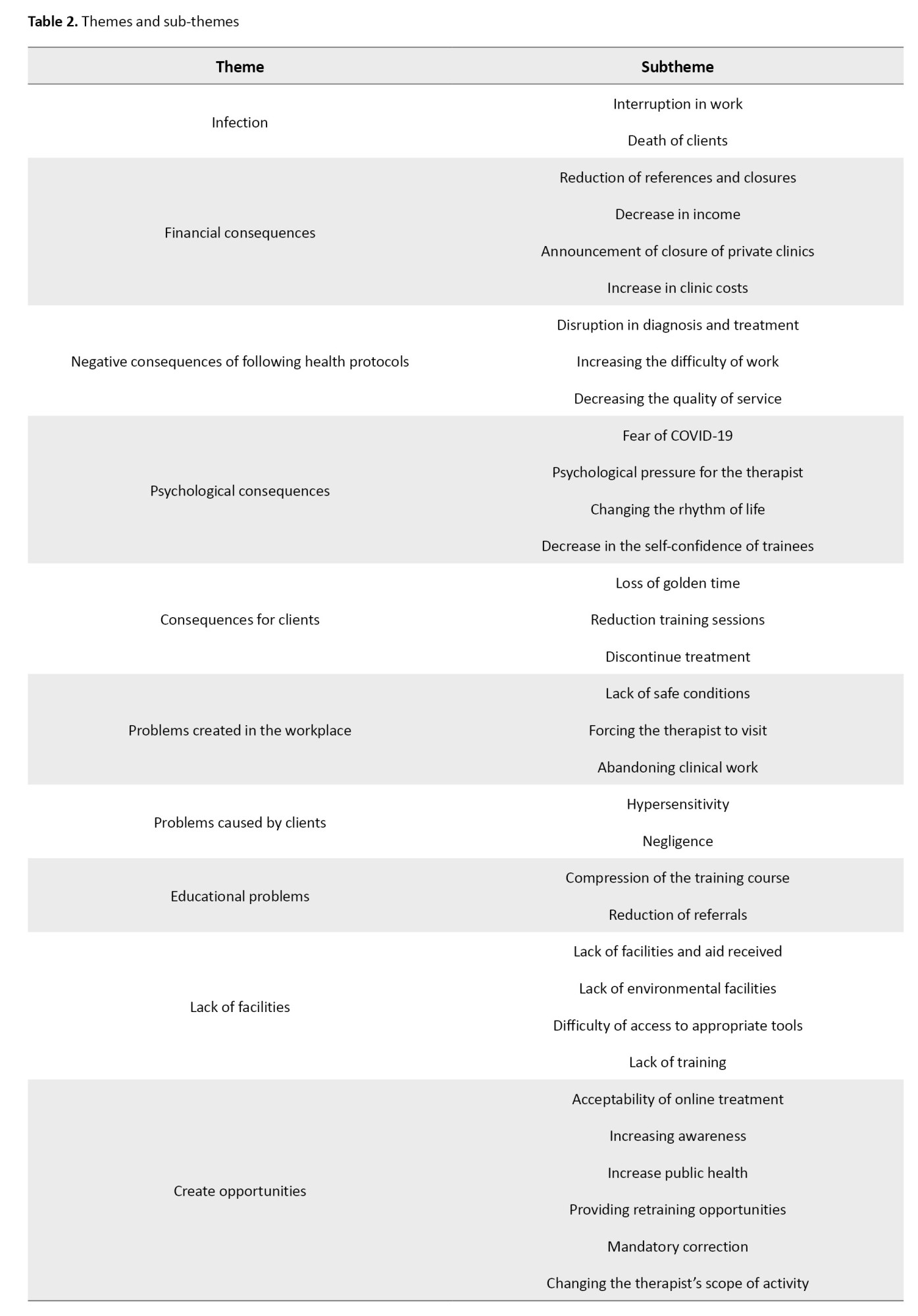

A total of 331 codes were extracted from the 21 interviews, from which 33 sub-themes and 10 themes emerged, as detailed in Table 2.

Infection

The participants discussed the impact of COVID-19, highlighting two significant sub-themes: “Interruption in work” and “death of clients.” The infection of either the therapist or client necessitated adherence to quarantine protocols, disrupting therapy sessions. Moreover, the vulnerability of some clients, particularly those with underlying health conditions or those of advanced age who were often receiving treatment for dysphagia or aphasia, led to client fatalities.

Financial consequences

Financial repercussions such as “reduction of referrals and closures,” “decrease in income,” “announcement of the closure of private clinics,” and “increasing clinic costs” were also significant challenges faced by therapists. All participants reported a drop in referrals from mild to severe depending on their place of workplace, with the most substantial reductions occurring during peak periods of the disease and in private clinics. Hospital outpatient visits also decreased. Most participants experienced a complete shutdown at the pandemic’s outset, which adversely affected their income. Three therapists with fixed incomes from universities and hospitals did not encounter this issue. The financial strain led to the closure of some private clinics and imposed additional costs on clinic owners for purchasing disinfectants, thermometers, masks, gloves, ventilation equipment, and costs related to re-advertisements post-reopening.

Negative consequences of following health protocols

Compliance with health protocols during work led to “disruption in diagnosis and treatment”, “increased difficulty of work” and “decreased quality of services”. PPE, such as shields, glasses, and masks impaired the therapists’ vision, caused light reflection, obscured visual cues, distorted sound quality, and complicated communication—particularly challenging when working with child clients during evaluations and treatments. Transparent masks would fog up over time, rendering them practically ineffective. Maintaining social distance eliminated the possibility of providing tactile cues and instructions. Keeping the windows open for ventilation presented problems, such as exposure to cold or heat, depending on the season, and disruptive noise from outside. All these factors presented significant challenges for therapists. Also, PPE causes fatigue, thirst, vocal strain, and lack of physical energy in therapists. One of the therapists said:

Code 3: “It was difficult for us to diagnose with glasses (stroboscopy) because we could hardly see the monitor".

Psychological consequences

Therapists discussed their unpleasant psychological experiences of the pandemic in the form of four sub-themes. The first one was “fear of COVID-19”. Therapists working in high-risk environments were worried about getting infected and passing the virus to their families, which created “psychological pressure for therapists” along with economic problems and reduced social connections. The pandemic caused surprises and changes in people’s social, professional, and personal lives. Therapists considered this “change in the rhythm of life” to be one of the psychological consequences of the pandemic. On the other hand, the therapists whose part of training coincided with the outbreak of COVID-19 faced educational problems, which caused “a decrease in their self-confidence” to start working.

Consequences for clients

«Loss of golden time”, “reduction of training sessions” and “discontinue of treatment” were negative consequences for clients. The closure of clinics at the beginning of the pandemic, the fear of infection, and the quarantine policies during the pandemic period led to a reduction in treatment sessions and sometimes clients leaving the treatment and finally, losing the golden time of treatment for some clients.

Problems created in the workplace

“Lack of safe conditions”, “forcing the therapist to visit” and “abandoning clinical work” were among the problems created in the work environment following the pandemic. The non-standard building of some clinics, the hospital turning into a COVID-19 center, the patient’s infection, and the home conditions of home visit patients led to the loss of safe conditions for therapists. In some centers, despite the symptoms being seen in the client, admission was still done and the therapist had to visit the client. Sometimes the problems in the workplace were so great that the therapists resigned.

Problems caused by clients

The “oversensitivity” of some clients regarding the observance of health protocols and their constant reminders prevented them from continuing with the previous quality of work. Sometimes the high anxiety of the family led to leaving the treatment or changing the clinic. On the other hand, some clients were “negligent” in complying with health issues or informing the therapist about their infection or being a carrier.

Educational problems

The therapists whose training coincided with the pandemic experienced “compression of the training course” and “reduction of referrals”, which led to a decrease in the training time for each lesson unit and a decrease in the follow-up time of the referral sessions by the trainees and a decrease in referrals. These issues negatively impacted their clinical training.

Lack of facilities

"Lack of facilities and received aid”, “lack of environmental facilities”, “difficulty of access to appropriate tools” and “lack of training” were among the main deficiencies of this course. Most therapists did not receive any facilities from their employers and related organizations regarding insurance, taxes, and license renewal. Those working in hospitals and coronavirus units lacked special support, with the only assistance being the allocation of vaccines at the start of the national vaccination campaign. Many therapists worked in environments lacking adequate ventilation, rest areas, and eating spaces. The scarcity of masks and gloves early in the pandemic, the high cost and rarity of transparent masks, and some necessary safety tools were additional challenges. There was also a notable lack of training on infection control, hygiene in hospitals and public centers, telemedicine principles, and specialized clinical workshops tailored to pandemic conditions.

Creating opportunities

Therapists also addressed six positive consequences of the pandemic, such as the “acceptability of online treatment”. During this period, the forced expansion of online treatments was met with favorable acceptance by society. The significant presence of speech therapists in virtual spaces and the demand for speech therapy services by COVID-19 patients led to “increased awareness” among specialists and the general public about the services offered in this field. The next positive aspect was “increased public health” in all places. Mandatory vacations and free time allowed therapists “Retraining opportunities” to update their knowledge. “Mandatory correction” in bedside methods, necessitated by adherence to health protocols, improved treatment quality in some cases. “Changing the scope of the therapist’s activities” enabled some individuals to explore new job opportunities, both related and unrelated to their field, in order to meet expenses. One of the therapists said:

Code 10: «We used the conditions of online work and organized online webinars for speech therapists».

Discussion

Being exposed to COVID-19 and contracting it was one of the consequences of the pandemic for therapists, as noted in other studies [6]. In addition to physical consequences, this disease also had financial repercussions. Being infected with COVID-19 led to quarantine, and since many therapists did not have employment insurance and their income depended on client visits, they lost their income during the quarantine period. The drop in referrals and reduction in working hours, which has also been reported in other studies [11], varied across different work environments. In most hospital settings, there was no significant decrease in income because working hours remained the same as before. However, those working in private clinics, rehabilitation centers, and other environments experienced closures, temporary unemployment, and significant financial damage [6]. The increase in clinic costs for the provision of protective equipment emerged as one of the financial consequences identified in this study.

The use of PPE led to disruptions in communication, assessment, and treatment. These included disruptions in the exchange of therapeutic information, loss of facial expressions, increased work difficulty, voice discomfort, and physical and mental fatigue of therapists [9, 16-19]. Consequently, the negative effects caused by the use of these devices led to a decrease in the quality of services, particularly as the pandemic was a new situation and it was difficult for people to adapt to it.

The pandemic also had psychological consequences for therapists. The fear of contracting a new, unknown disease, its transmission to relatives, and anxiety caused by working in a hospital environment, especially in the specialized departments for COVID-19 and ICUs, were consequences mentioned in other studies as well [20, 21]. Fear of the future and changes in work and personal life routines created a psychological burden for the treatment staff [18, 22]. The report of a lack of anxiety in some therapists was also attributed to individual differences in anxiety control skills and people’s adaptation to the conditions as the pandemic prolonged.

The negative consequences of the pandemic for clients have also been discussed in the study by Tohidast et al. (2020). They noted the critical timing and age sensitivity in some children, such that any disruption in the provision of treatment, like those caused by a pandemic, leads to the persistence of speech problems and a decrease in the quality of life [8].

Failure to provide safety conditions in the workplace, such as clinic locations in areas with a high risk of contamination or hospitals, or the lack of accurate information about the possibility of contamination, forced therapists to visit infected clients due to clinic officials’ mandates clients’ concealment of their illness or excessive sensitivity created additional unfavorable conditions for therapists. These pressures, along with the psychological pressures caused by the pandemic, sometimes led therapists to leave clinical work, thereby increasing their economic burdens.

Speech therapy trainees faced significant challenges in their training. The compression of training courses, reduced client numbers, professors’ lack of experience with virtual education, and the absence of virtual educational facilities caused issues for students in terms of knowledge acquisition and psychological well-being, a phenomenon also reported in studies across other fields [23, 24]. It seems that designing new educational protocols that meet students’ needs in similar crisis situations is a topic worthy of discussion.

The next issue was the lack of facilities in various areas, such as insufficient space, inadequate windows, and proper ventilation, difficult access due to cost and the scarcity of some tools to facilitate treatment, the lack of masks and other PPE at the beginning of the pandemic, which led to the reuse of used protective equipment. This finding highlights the need to improve the treatment environment monitor it and facilitate access to treatment tools [19, 25]. Providing the necessary tools for therapists in some centers like hospitals was not prioritized by the relevant authorities. Special facilities provided for medical staff in contact with COVID-19 patients were not extended to speech therapists, even though therapists working in ICUs were in direct contact with infected individuals. This disparity in the allocation of resources is also noted in other reports [26]. One of the main complaints of the participants was the lack of support, including financial support, :union: support, and appreciation of therapists working in the COVID-19 treatment teams. Unlike in nursing studies, where financial, and emotional support, and organizational and public encouragement are identified as factors enhancing social aspects and feelings of worth [27, 28], such support was lacking in this field. Another deficiency was the lack of training on infection control and specialized training to overcome critical situations. While general training was made available by the media, specialized training, including safe communication methods, choosing the right tools, modification of methods, guidance on conducting online meetings effectively, and managing speech and swallowing disorders related to COVID-19, was not provided to specialists in this field. Often, they had to resort to trial and error or rely on externally published sources, a situation also observed in other reports [29]. This problem shows the crucial role of speech therapy associations and universities in providing necessary training during a pandemic.

The increase in public health was mentioned as one of the positive consequences of the pandemic [30], which reduced the prevalence of many other infectious diseases and more consistent client meetings. This situation forced a reform that extended beyond health issues alone. Sometimes these reforms improved assessment and treatment methods. The limitations of face-to-face visits led therapists to be creative in communicating with clients, which sometimes had positive results, and some former communication methods were changed forever. Mandatory correction is one of the new findings in this study. Another positive outcome was the community’s acceptance of online treatment [31]. The deprivation of face-to-face meetings led to the widespread use of online meetings, effectively testing its acceptance by the public. Also, the increase in speech therapists’ online activities raised both general and specialized community awareness about the services in this field. The increasing need for the services of speech therapists in ICUs for patients with COVID-19, which was at the center of attention of various specialists, such as doctors during the pandemic, raised their knowledge of this field. Closures and reduced working hours were an opportunity for therapists to take on new roles, which were sometimes mandatory. This role change was a positive experience for some people and increased their scope of activity even after the pandemic. In some instances, these changes were temporary and dependent on the policies of the place of employment. Another study reported role changes to meet new demands in medical centers [32]; however, in the present study, the role change was often a personal decision to compensate for decreased income and was typically related to the individuals’ expertise.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created many problems in many professions, especially jobs related to health and treatment, and had many negative consequences for speech-language pathologists in various financial, occupational, physical, and mental health dimensions. Reviewing these highlights the existing technical and scientific deficiencies in dealing with unexpected crises and calls for attention from relevant organizations to mitigate and prevent such problems in the future. On the other hand, in addition to the negative consequences, participants in this study also reported positive outcomes, such as the expansion of online treatment following the outbreak of COVID-19, which led to the correction, and in some cases, the improvement of the quality of services that can be provided. This demonstrates the potential of the field of speech-language pathology to adapt to various conditions and the dynamism and flexibility of its practitioners in continuing to provide health services to clients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The proposal for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.14010445).

Funding

This article is taken from the master’s thesis of Zahra Ensafi, approved by Department of Speech Therapy, Iran University of Medical Sciences and supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors actively participated in all stages of this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the dear professors and respected participants who helped them in the implementation of this research project.

References

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019 created critical conditions around the world that continued until 2023 [1, 2]. The virus mainly leads to respiratory tract infections in humans [3]. The rapid transmission of the virus led to significant disruptions in people’s work and daily lives [4, 5]. One of the professions affected by the pandemic was speech-language pathology.

Speech-language pathologists, due to the clinical nature of their work, often engage in face-to-face communication and are exposed to the upper airway structures of clients during procedures such as oral examinations and stroboscopy. Therefore, the risk of contracting COVID-19 in these therapists is high [6].

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is crucial, yet such equipment can hinder treatment by obscuring visual, auditory, and speech communication. For example, wearing glasses and masks reduces eye contact and facial expressions. Additionally, the pandemic led to fewer client referrals, which subsequently had financial repercussions [6, 7, 8, 9]. Despite the announcement of the end of the critical situation of the pandemic in 2023 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [10], acknowledging the challenges and impacts this disease has had on the field of speech therapy has underscored the importance of learning from the complex conditions of the pandemic. On the other hand, considering the respiratory transmission of this disease and the high prevalence of respiratory diseases in the cold seasons of the year, the experiences of therapists during this period can be invaluable for future similar situations.

Previous studies exploring the effects of the pandemic on this field through surveys do not fully capture the therapists’ experiences during these crises. Furthermore, people’s experiences of a phenomenon can vary significantly due to geographical differences and available resources [11-13]. Conducting a qualitative study can provide a deeper understanding of the consequences of this pandemic and a comprehensive insight into this phenomenon, helping professionals in this field to address deficiencies, create suitable infrastructures, and enhance future performance. Therefore, the objective of this study is to explore the challenges and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinical activities of speech-language pathologists.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted using the interpretive phenomenological analysis method. In this method, the researcher discovers the personal experience of the participants to gain a deeper understanding of the desired phenomenon [14].

Participants and sampling method

Twenty-one speech-language pathologists who were actively engaged in clinical activities either in-person or virtually during the pandemic participated in this research. Sampling was conducted purposefully using the maximum variation technique to cover all treatment environments and areas of speech disorders.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews that started with open-ended questions, such as: “Please describe your experience of clinical work during the pandemic” and “How has the pandemic changed your work?”. The interviewer used a guide to steer the discussion and address the main topics. Each interview lasted between 30 to 60 minutes and was audio-recorded with the participant’s consent.

Analysis began immediately after the first interview and proceeded concurrently with subsequent interviews up to the 21st interview. The interviews were transcribed and then coded using MAXQDA software, version 2020. The coded data were analyzed by thematic analysis method. In this method, codes are first grouped into clusters and then themes are formed. Then, the categories are refined, and specific names are assigned to each theme.

Trustworthiness

To enhance the scientific accuracy and reliability of the data, four criteria outlined by Lincoln and Goba were applied: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [15]. In order to increase the credibility of the data, the samples with the maximum variation were selected and a part of the data was provided to the participants after analysis to confirm the accuracy of the information. In order to increase the transferability, the sampling and analysis steps were carefully described so that the readers could make a correct judgment about the use of the findings in similar situations. In terms of dependability, in addition to the detailed description of all the stages of the research, in order to make it possible for the readers to follow the researcher’s decisions, the data were audited by another member of the research team. In order to increase the confirmability, the data were provided to other members of the research team to minimize researcher bias.

Results

Participants

Twenty-one speech-language pathologists who conducted clinical activities both face-to-face and online during the pandemic participated in this study. The characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1.

A total of 331 codes were extracted from the 21 interviews, from which 33 sub-themes and 10 themes emerged, as detailed in Table 2.

Infection

The participants discussed the impact of COVID-19, highlighting two significant sub-themes: “Interruption in work” and “death of clients.” The infection of either the therapist or client necessitated adherence to quarantine protocols, disrupting therapy sessions. Moreover, the vulnerability of some clients, particularly those with underlying health conditions or those of advanced age who were often receiving treatment for dysphagia or aphasia, led to client fatalities.

Financial consequences

Financial repercussions such as “reduction of referrals and closures,” “decrease in income,” “announcement of the closure of private clinics,” and “increasing clinic costs” were also significant challenges faced by therapists. All participants reported a drop in referrals from mild to severe depending on their place of workplace, with the most substantial reductions occurring during peak periods of the disease and in private clinics. Hospital outpatient visits also decreased. Most participants experienced a complete shutdown at the pandemic’s outset, which adversely affected their income. Three therapists with fixed incomes from universities and hospitals did not encounter this issue. The financial strain led to the closure of some private clinics and imposed additional costs on clinic owners for purchasing disinfectants, thermometers, masks, gloves, ventilation equipment, and costs related to re-advertisements post-reopening.

Negative consequences of following health protocols

Compliance with health protocols during work led to “disruption in diagnosis and treatment”, “increased difficulty of work” and “decreased quality of services”. PPE, such as shields, glasses, and masks impaired the therapists’ vision, caused light reflection, obscured visual cues, distorted sound quality, and complicated communication—particularly challenging when working with child clients during evaluations and treatments. Transparent masks would fog up over time, rendering them practically ineffective. Maintaining social distance eliminated the possibility of providing tactile cues and instructions. Keeping the windows open for ventilation presented problems, such as exposure to cold or heat, depending on the season, and disruptive noise from outside. All these factors presented significant challenges for therapists. Also, PPE causes fatigue, thirst, vocal strain, and lack of physical energy in therapists. One of the therapists said:

Code 3: “It was difficult for us to diagnose with glasses (stroboscopy) because we could hardly see the monitor".

Psychological consequences

Therapists discussed their unpleasant psychological experiences of the pandemic in the form of four sub-themes. The first one was “fear of COVID-19”. Therapists working in high-risk environments were worried about getting infected and passing the virus to their families, which created “psychological pressure for therapists” along with economic problems and reduced social connections. The pandemic caused surprises and changes in people’s social, professional, and personal lives. Therapists considered this “change in the rhythm of life” to be one of the psychological consequences of the pandemic. On the other hand, the therapists whose part of training coincided with the outbreak of COVID-19 faced educational problems, which caused “a decrease in their self-confidence” to start working.

Consequences for clients

«Loss of golden time”, “reduction of training sessions” and “discontinue of treatment” were negative consequences for clients. The closure of clinics at the beginning of the pandemic, the fear of infection, and the quarantine policies during the pandemic period led to a reduction in treatment sessions and sometimes clients leaving the treatment and finally, losing the golden time of treatment for some clients.

Problems created in the workplace

“Lack of safe conditions”, “forcing the therapist to visit” and “abandoning clinical work” were among the problems created in the work environment following the pandemic. The non-standard building of some clinics, the hospital turning into a COVID-19 center, the patient’s infection, and the home conditions of home visit patients led to the loss of safe conditions for therapists. In some centers, despite the symptoms being seen in the client, admission was still done and the therapist had to visit the client. Sometimes the problems in the workplace were so great that the therapists resigned.

Problems caused by clients

The “oversensitivity” of some clients regarding the observance of health protocols and their constant reminders prevented them from continuing with the previous quality of work. Sometimes the high anxiety of the family led to leaving the treatment or changing the clinic. On the other hand, some clients were “negligent” in complying with health issues or informing the therapist about their infection or being a carrier.

Educational problems

The therapists whose training coincided with the pandemic experienced “compression of the training course” and “reduction of referrals”, which led to a decrease in the training time for each lesson unit and a decrease in the follow-up time of the referral sessions by the trainees and a decrease in referrals. These issues negatively impacted their clinical training.

Lack of facilities

"Lack of facilities and received aid”, “lack of environmental facilities”, “difficulty of access to appropriate tools” and “lack of training” were among the main deficiencies of this course. Most therapists did not receive any facilities from their employers and related organizations regarding insurance, taxes, and license renewal. Those working in hospitals and coronavirus units lacked special support, with the only assistance being the allocation of vaccines at the start of the national vaccination campaign. Many therapists worked in environments lacking adequate ventilation, rest areas, and eating spaces. The scarcity of masks and gloves early in the pandemic, the high cost and rarity of transparent masks, and some necessary safety tools were additional challenges. There was also a notable lack of training on infection control, hygiene in hospitals and public centers, telemedicine principles, and specialized clinical workshops tailored to pandemic conditions.

Creating opportunities

Therapists also addressed six positive consequences of the pandemic, such as the “acceptability of online treatment”. During this period, the forced expansion of online treatments was met with favorable acceptance by society. The significant presence of speech therapists in virtual spaces and the demand for speech therapy services by COVID-19 patients led to “increased awareness” among specialists and the general public about the services offered in this field. The next positive aspect was “increased public health” in all places. Mandatory vacations and free time allowed therapists “Retraining opportunities” to update their knowledge. “Mandatory correction” in bedside methods, necessitated by adherence to health protocols, improved treatment quality in some cases. “Changing the scope of the therapist’s activities” enabled some individuals to explore new job opportunities, both related and unrelated to their field, in order to meet expenses. One of the therapists said:

Code 10: «We used the conditions of online work and organized online webinars for speech therapists».

Discussion

Being exposed to COVID-19 and contracting it was one of the consequences of the pandemic for therapists, as noted in other studies [6]. In addition to physical consequences, this disease also had financial repercussions. Being infected with COVID-19 led to quarantine, and since many therapists did not have employment insurance and their income depended on client visits, they lost their income during the quarantine period. The drop in referrals and reduction in working hours, which has also been reported in other studies [11], varied across different work environments. In most hospital settings, there was no significant decrease in income because working hours remained the same as before. However, those working in private clinics, rehabilitation centers, and other environments experienced closures, temporary unemployment, and significant financial damage [6]. The increase in clinic costs for the provision of protective equipment emerged as one of the financial consequences identified in this study.

The use of PPE led to disruptions in communication, assessment, and treatment. These included disruptions in the exchange of therapeutic information, loss of facial expressions, increased work difficulty, voice discomfort, and physical and mental fatigue of therapists [9, 16-19]. Consequently, the negative effects caused by the use of these devices led to a decrease in the quality of services, particularly as the pandemic was a new situation and it was difficult for people to adapt to it.

The pandemic also had psychological consequences for therapists. The fear of contracting a new, unknown disease, its transmission to relatives, and anxiety caused by working in a hospital environment, especially in the specialized departments for COVID-19 and ICUs, were consequences mentioned in other studies as well [20, 21]. Fear of the future and changes in work and personal life routines created a psychological burden for the treatment staff [18, 22]. The report of a lack of anxiety in some therapists was also attributed to individual differences in anxiety control skills and people’s adaptation to the conditions as the pandemic prolonged.

The negative consequences of the pandemic for clients have also been discussed in the study by Tohidast et al. (2020). They noted the critical timing and age sensitivity in some children, such that any disruption in the provision of treatment, like those caused by a pandemic, leads to the persistence of speech problems and a decrease in the quality of life [8].

Failure to provide safety conditions in the workplace, such as clinic locations in areas with a high risk of contamination or hospitals, or the lack of accurate information about the possibility of contamination, forced therapists to visit infected clients due to clinic officials’ mandates clients’ concealment of their illness or excessive sensitivity created additional unfavorable conditions for therapists. These pressures, along with the psychological pressures caused by the pandemic, sometimes led therapists to leave clinical work, thereby increasing their economic burdens.

Speech therapy trainees faced significant challenges in their training. The compression of training courses, reduced client numbers, professors’ lack of experience with virtual education, and the absence of virtual educational facilities caused issues for students in terms of knowledge acquisition and psychological well-being, a phenomenon also reported in studies across other fields [23, 24]. It seems that designing new educational protocols that meet students’ needs in similar crisis situations is a topic worthy of discussion.

The next issue was the lack of facilities in various areas, such as insufficient space, inadequate windows, and proper ventilation, difficult access due to cost and the scarcity of some tools to facilitate treatment, the lack of masks and other PPE at the beginning of the pandemic, which led to the reuse of used protective equipment. This finding highlights the need to improve the treatment environment monitor it and facilitate access to treatment tools [19, 25]. Providing the necessary tools for therapists in some centers like hospitals was not prioritized by the relevant authorities. Special facilities provided for medical staff in contact with COVID-19 patients were not extended to speech therapists, even though therapists working in ICUs were in direct contact with infected individuals. This disparity in the allocation of resources is also noted in other reports [26]. One of the main complaints of the participants was the lack of support, including financial support, :union: support, and appreciation of therapists working in the COVID-19 treatment teams. Unlike in nursing studies, where financial, and emotional support, and organizational and public encouragement are identified as factors enhancing social aspects and feelings of worth [27, 28], such support was lacking in this field. Another deficiency was the lack of training on infection control and specialized training to overcome critical situations. While general training was made available by the media, specialized training, including safe communication methods, choosing the right tools, modification of methods, guidance on conducting online meetings effectively, and managing speech and swallowing disorders related to COVID-19, was not provided to specialists in this field. Often, they had to resort to trial and error or rely on externally published sources, a situation also observed in other reports [29]. This problem shows the crucial role of speech therapy associations and universities in providing necessary training during a pandemic.

The increase in public health was mentioned as one of the positive consequences of the pandemic [30], which reduced the prevalence of many other infectious diseases and more consistent client meetings. This situation forced a reform that extended beyond health issues alone. Sometimes these reforms improved assessment and treatment methods. The limitations of face-to-face visits led therapists to be creative in communicating with clients, which sometimes had positive results, and some former communication methods were changed forever. Mandatory correction is one of the new findings in this study. Another positive outcome was the community’s acceptance of online treatment [31]. The deprivation of face-to-face meetings led to the widespread use of online meetings, effectively testing its acceptance by the public. Also, the increase in speech therapists’ online activities raised both general and specialized community awareness about the services in this field. The increasing need for the services of speech therapists in ICUs for patients with COVID-19, which was at the center of attention of various specialists, such as doctors during the pandemic, raised their knowledge of this field. Closures and reduced working hours were an opportunity for therapists to take on new roles, which were sometimes mandatory. This role change was a positive experience for some people and increased their scope of activity even after the pandemic. In some instances, these changes were temporary and dependent on the policies of the place of employment. Another study reported role changes to meet new demands in medical centers [32]; however, in the present study, the role change was often a personal decision to compensate for decreased income and was typically related to the individuals’ expertise.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created many problems in many professions, especially jobs related to health and treatment, and had many negative consequences for speech-language pathologists in various financial, occupational, physical, and mental health dimensions. Reviewing these highlights the existing technical and scientific deficiencies in dealing with unexpected crises and calls for attention from relevant organizations to mitigate and prevent such problems in the future. On the other hand, in addition to the negative consequences, participants in this study also reported positive outcomes, such as the expansion of online treatment following the outbreak of COVID-19, which led to the correction, and in some cases, the improvement of the quality of services that can be provided. This demonstrates the potential of the field of speech-language pathology to adapt to various conditions and the dynamism and flexibility of its practitioners in continuing to provide health services to clients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The proposal for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.14010445).

Funding

This article is taken from the master’s thesis of Zahra Ensafi, approved by Department of Speech Therapy, Iran University of Medical Sciences and supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors actively participated in all stages of this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the dear professors and respected participants who helped them in the implementation of this research project.

References

- Hite LM, McDonald KS. Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Hum Resour Dev Int. 2020; 23(4):427-37. [DOI:10.1080/13678868.2020.1779576]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. New Engl J Med. 2020; 382(13):1199-207. [Link]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020; 395(10223):507-13. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7] [PMID]

- Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020; 42(3):232-5. [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008] [PMID]

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020; 76:71-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034] [PMID]

- Kearney A, Searl J, Erickson-DiRenzo E, Doyle PC. The impact of COVID-19 on speech-language pathologists engaged in clinical practices with elevated coronavirus transmission risk. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2021; 30(4):1673-85. [DOI:10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00325] [PMID]

- Bandaru S, Augustine A, Lepcha A, Sebastian S, Gowri M, Philip A, Mammen M. The effects of N95 mask and face shield on speech perception among healthcare workers in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic scenario. J Laryngol & Otol. 2020; 134(10):895-8. [DOI:10.1017/S0022215120002108] [PMID]

- Tohidast SA, Mansuri B, Bagheri R, Azimi H. Provision of speech-language pathology services for the treatment of speech and language disorders in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Problems, concerns, and solutions. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020; 138:110262. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110262] [PMID]

- Knollman-Porter K, Burshnic VL. Optimizing effective communication while wearing a mask during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020; 46(11):7-11. [DOI:10.3928/00989134-20201012-02] [PMID]

- WHO. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: World Health organization: 2023. [Link]

- Chadd K, Moyse K, Enderby P. Impact of COVID-19 on the speech and language therapy profession and their patients. Front Neurol. 2021; 12:629190. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2021.629190] [PMID]

- Gunjawate DR, Ravi R, Yerraguntla K, Rajashekhar B, Verma A. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on professional practices of audiologists and speech-language pathologists in India: A knowledge, attitude and practices survey. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021; 9:110-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.07.009] [PMID]

- Stead A, Vinson M, Michael P, Frank D. The Impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice in medically based settings: Speech-language pathologists’ perspectives. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 2022; 1-18. [DOI:10.1044/2021_PERSP-21-00166]

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE publications; 2021. [Link]

- Boswell C, Cannon S. Introduction to nursing research: Incorporating evidence-based practice. Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018. [Link]

- Mheidly N, Fares MY, Zalzale H, Fares J. Effect of face masks on interpersonal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020; 8:582191. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2020.582191] [PMID]

- Shekaraiah S, Suresh K. Effect of face mask on voice production during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Voice. 2024; 38(2):446-57. [PMID]

- Rao H, Mancini D, Tong A, Khan H, Santacruz Gutierrez B, Mundo W, et al. Frontline interdisciplinary clinician perspectives on caring for patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(5):e048712. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048712] [PMID]

- Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C, Alazmani-Noodeh F, Hakimi H, Ranjbar H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Am J Infect Control. 2021; 49(5):547-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001] [PMID]

- Cawcutt KA, Starlin R, Rupp ME. Fighting fear in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020; 41(10):1192-3. [DOI:10.1017/ice.2020.315] [PMID]

- Khattak SR, Saeed I, Rehman SU, Fayaz M. Impact of fear of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nurses in Pakistan. J Loss Trauma. 2021; 26(5):421-35. [DOI:10.1080/15325024.2020.1814580]

- Jow S, Doshi S, Desale S, Malmut L. Mental health impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on therapists at an inpatient rehabilitation facility. PM R. 2023; 15(2):168-75. [DOI:10.1002/pmrj.12860] [PMID]

- Harries AJ, Lee C, Jones L, Rodriguez RM, Davis JA, Boysen-Osborn M, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021; 21(1):14. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1] [PMID]

- Mortazavi F, Salehabadi R, Sharifzadeh M, Ghardashi F. Students’ perspectives on the virtual teaching challenges in the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021; 10:59. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_861_20] [PMID]

- Hoel V, Zweck CV, Ledgerd R, World Federation of Occupational Therapists. The impact of Covid-19 for occupational therapy: Findings and recommendations of a global survey. World Fed OccupTher Bull. 2021; 77(2):69-76. [DOI:10.1080/14473828.2020.1855044]

- Igwesi-Chidobe CN, Anyaene C, Akinfeleye A, Anikwe E, Gosselink R. Experiences of physiotherapists involved in front-line management of patients with COVID-19 in Nigeria: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022; 12(4):e060012. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060012] [PMID]

- Varasteh S, Esmaeili M, Mazaheri M. Factors affecting Iranian nurses’ intention to leave or stay in the profession during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Nurs Rev. 2022; 69(2):139-49.[DOI:10.1111/inr.12718] [PMID]

- Sheng Q, Zhang X, Wang X, Cai C. The influence of experiences of involvement in the COVID‐19 rescue task on the professional identity among Chinese nurses: A qualitative study. J Nurs Manag. 2020; 28(7):1662-9. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13122] [PMID]

- Palacios-Ceña D, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Florencio LL, Palacios-Ceña M, de-la-Llave-Rincón AI. Future challenges for physical therapy during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study on the experience of physical therapists in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8368. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18168368] [PMID]

- Alghamdi AA. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and educational aspects of Saudi university students’ lives. PLoS One. 2021; 16(4):e0250026. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0250026] [PMID]

- Aggarwal K, Patel R, Ravi R. Uptake of telepractice among speech-language therapists following COVID-19 pandemic in India. Speech Lang Hear. 2021; 24(4):228-34. [DOI:10.1080/2050571X.2020.1812034]

- Adams SN, Seedat J, Coutts K, Kater K-A. ‘We are in this together’voices of speech-language pathologists working in South African healthcare contexts during level 4 and level 5 lockdown of COVID-19. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2021; 68(1):e1-12. [DOI:10.4102/sajcd.v68i1.792] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Speech Therapy

Received: 2024/01/27 | Accepted: 2024/02/17 | Published: 2024/03/21

Received: 2024/01/27 | Accepted: 2024/02/17 | Published: 2024/03/21

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |