Volume 6, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2023)

Func Disabil J 2023, 6(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Iranpour F, Ghelichi L. The Effect of Vocal Warm up and Cool Down Exercises on the Acoustic Characteristics in Speech and Language Pathologists: A Pilot Study. Func Disabil J 2023; 6 (1) : 280.1

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-238-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-238-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation, Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,lghelichi@gmail.com

2- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation, Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Vocal cord dysfunction, Voice disorders, Warm-up exercises, Cool-down exercises, Speech-language pathology, Speech therapy, Vocal quality

Full-Text [PDF 890 kb]

(568 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2165 Views)

Full-Text: (1187 Views)

Introduction

Voice performance is a fundamental process that has a critical impact on people’s daily communication and professional lives [1, 2]. Professional voice users are considered as a group at risk of voice disorder [1, 2]. Speech and language pathologists (SLPs) are professional voice users who use their voices for therapy, counseling, conferencing, and public speaking that goes beyond ordinary daily conversations [3, 4]. According to Gottliebson et al., the prevalence of voice disorders in speech and language pathologist students was 12% [3]. Several studies showed that vocal problems, such as fatigue, hoarseness, irritation in the larynx, low pitch, breathiness, straining, frequency breaks, and resonance changes are prevalent in SLPs [3, 4].

The vocal training method includes three main approaches to prevent voice problems. The direct approach comprises of vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises (VWCE). The indirect approach includes vocal hygiene council and the third approach is a combination of direct and indirect strategies [4-6]. The vocal warm-up exercises affect the acoustic characteristics by increasing blood flow to the vocal fold muscles, reducing muscle viscosity, and decreasing fatigue [1, 5]. The vocal cool-down exercises lead to faster recovery time and return the speaking voice to normal more quickly [1, 7]. Studies conducted on the singers indicated that the VWCE improves vibrato characteristics due to improved vocal quality [1 7-11]. Santos et al. examined the difference in the impact of direct and indirect approaches on SLP and audiology students. They reported that the direct approach, including the VWCE, led to significant improvement in the voice quality [4]. Van Lierde et al. in a study on female students training for SLPs showed that warming up the vocal mechanism is beneficial to the objective vocal quality and the vocal performance in future SLPs [5]. A dearth of published studies investigates the effect of VWCE on SLPs with clinical activity. Therefore, this study was conducted to explore the effect of vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises on the acoustic characteristics of SLPs.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study to evaluate the effects of the VWCE on SLPs. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS). The consent form was obtained from all SLPs before taking part in the study.

Study participants

Eighteen participants were recruited from the School of Rehabilitation Sciences, IUMS. The inclusion criteria included age between 25-50 years, having at least 10 hours of clinical activity in a week, participants must have at least one year of clinical work experience, having no history of using effective drugs on the voice such as steroids, no history of pathological voice disorder and problems in hearing, neurological, velopharyngeal, and laryngological disorders, all the subjects were non-smoker and were aware and compliance with the vocal hygiene behavior. The exclusion criteria included reluctance to continue to collaborate in research.

Exercise program

The exercise program included VWCE. All the participants received 18 sessions of the exercise program, three times a week, every other day. The vocal warm-up exercises were performed for 10 minutes before clinical activity and the vocal cool-down exercises were performed for 10 minutes after clinical activity. The VWCE were included:

Lip and tongue trill. Production of the trill balances resonance, amplifies normal laryngeal tension, enhances coordination of respiration/phonation/articulation, and helps to reduce pharyngeal squeezing [12, 13].

Humming is used to achieve an improved balance of oronasal resonance and relaxes the articulations, and optimizes nasal resonance [12, 13].

Sigh and yawn, this technique moves the tongue forward and reduces extrinsic laryngeal muscle tension. Easy, natural airflow and phonation are fosters [12, 13].

Outcome measures

In this study, the acoustic characteristics including jitter, shimmer, and harmonic-to-noise rate (HNR) were used as outcome measures. These acoustic characteristics were measured before the exercise program (T0), after the end of the 9th session (T1), and after the end of the 18th session (T2).

Acoustic assessment

The Praat software, version 5.3.8.1 was used to extract the acoustic voice characteristics. The first and the last second of vocal samples were eliminated due to natural instability. The remaining second was analyzed.

Voice recording

The voice sample was recorded with a microphone coupled to a Zoom Corporation H5 Handy Recorder (4-4-3 Surugadai, Kanda, Chiyoda-ku,Tokyo 101-0062 Japan) at a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz and 16 bits, stored in the wav format. The microphone was placed at a distance of 5 cm from the mouth of the participants with an angle of 45 degrees and in a setting position. The procedure was performed in a silent room with noise kept below 40 dB. The vowel /a/ was sustained three times for 3 s in participation’s habitual frequency and intensity of speech.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 21. Descriptive (Mean±SE) and inferential analyses were performed for statistical data analysis. To analyze the normality of data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. One-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the effect of the VWCE on the outcome measures with time before the exercise program (T0), after the end of the 9th session (T1), after the end of the 18th session (T2) as the within-subject variable and then a Bonferroni adjustment test followed for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) of the changed scores were calculated to determine the treatment effects. The effect sizes were defined as <0.20 (negligible), between ≥0.20 and <0.50 (small), between ≥0.50 and <0.80 (moderate), and ≥0.80 (large) [14]. P≤0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

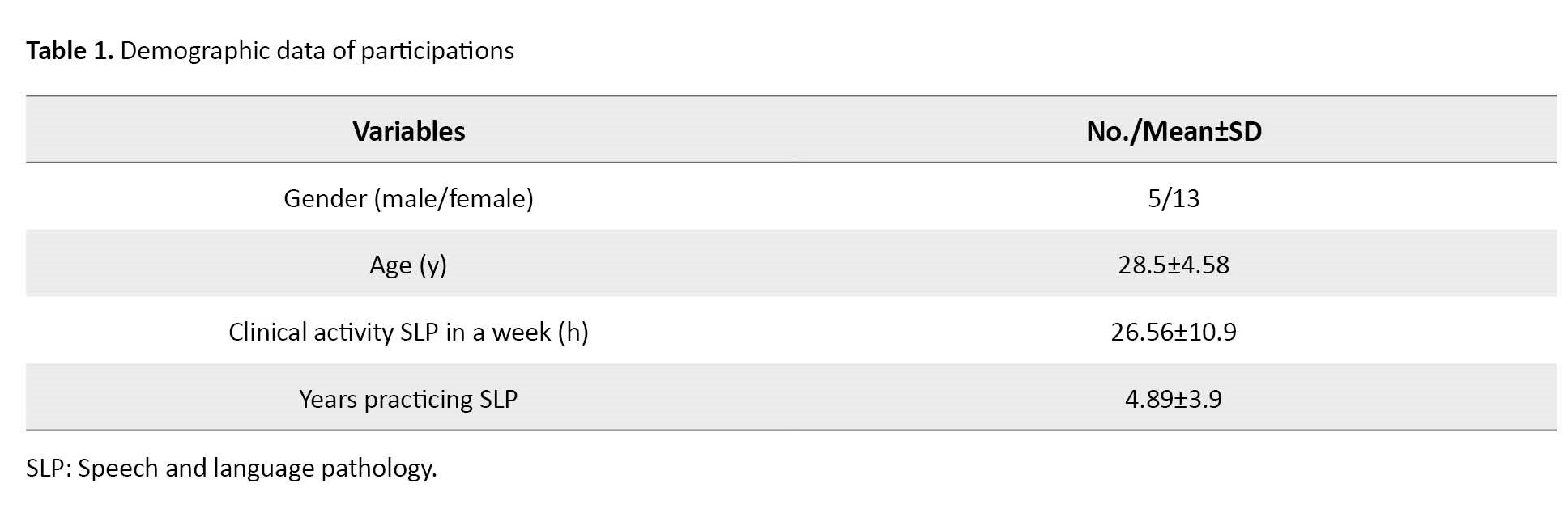

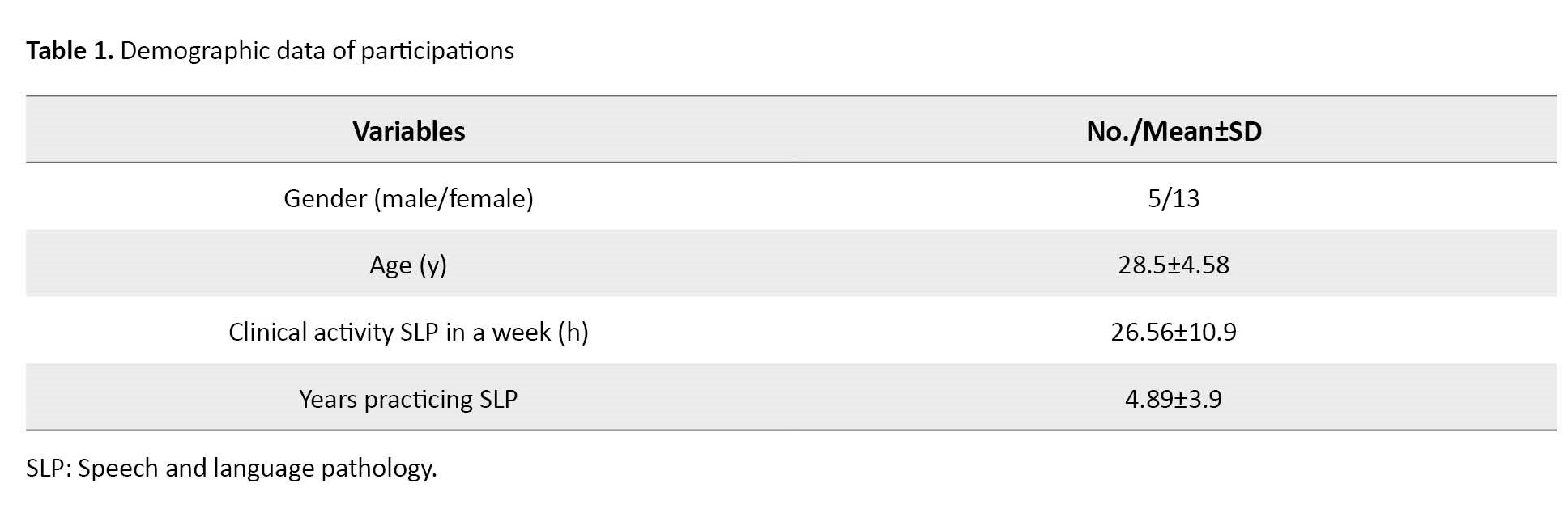

A total of 18 participants (5 men, 13 women) with a Mean±SD age of 28.5±4.5 years were included in the study. The Mean±SD clinical activity of the SLPs was 26.56±10.9 hours per week. Table 1 presents the details of the demographic characteristics of the participants.

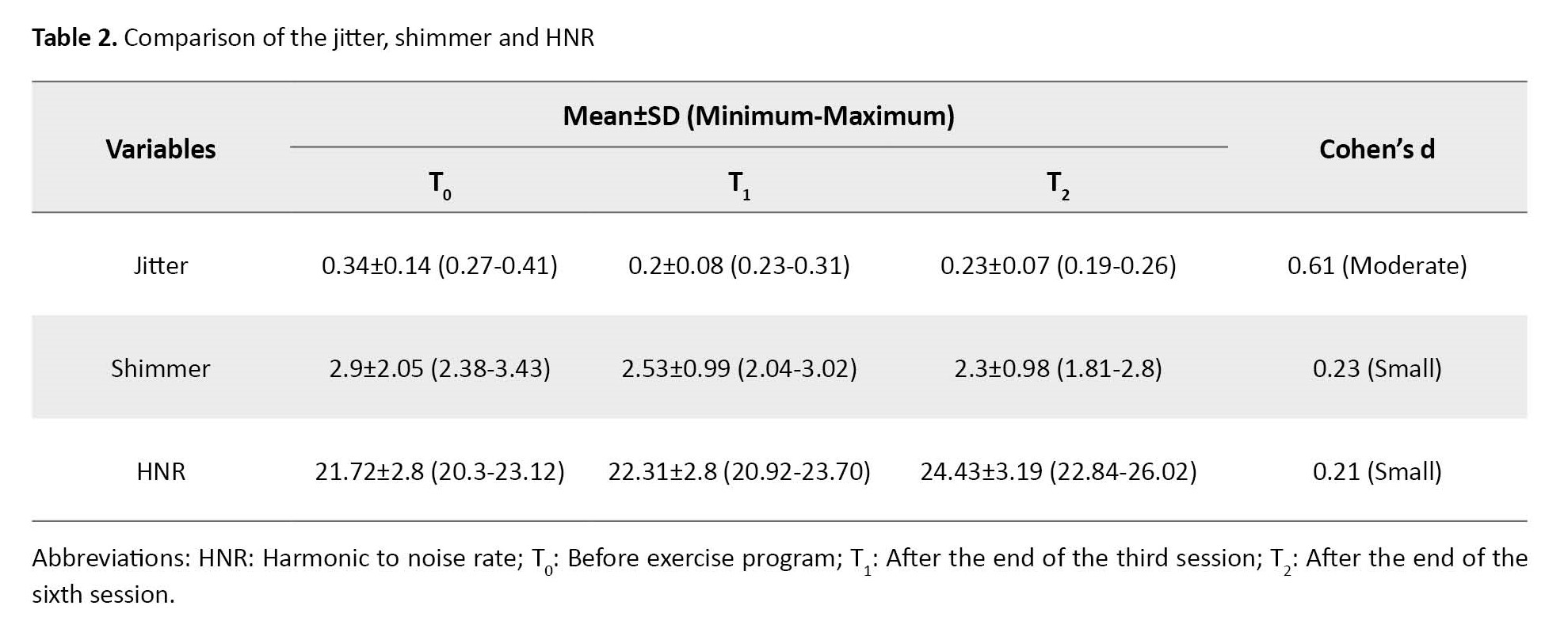

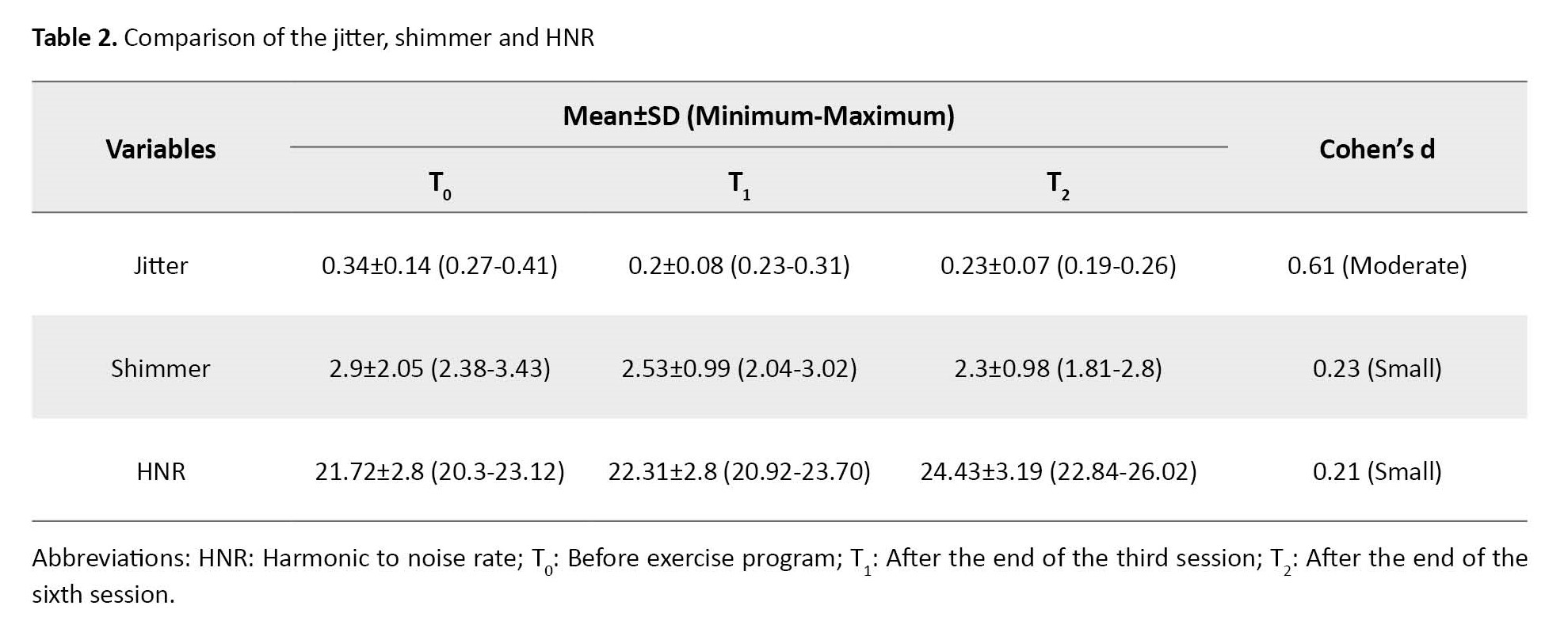

Jitter

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant decreases in the jitter after the VWCE. Bonferroni test indicated significant decreases at T1 and T2 compared to T0 (P<0.05). The jitter at T2 similar to that at T1 (P<0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was violated, the greenhouse Geisser correction was used. For the adjusted values, F(1.18, 0.10)=11.509, P<0.001. A moderate effect size was found for the jitter (d=0.61) (Table 2).

Shimmer

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant decreases in the shimmer after the VWCE. Bonferroni test showed significant decreases in T2 compared to T0 (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in T1 compared to T0 and T2 (P>0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was accepted, the Sphericity Assumed was used. For the adjusted values, F(2, 1.660)=4.949, P>0.05. A small effect size was found for shimmer (d=0.23) (Table 2).

Harmonic-to-noise rate (HNR)

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant increases in the HNR after the VWCE. Bonferroni test indicated a significant increase at T2 compared to T0 and T1 (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in T1 compared to T0 (P>0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was accepted, the assumed Sphericity was used. For the adjusted values, F(2.000, 36.677)=12.163, P>0.05. The small effect sizes were found for HNR (d=0.21) (Table 2).

Discussion

The SLPs are professional voice users who are at high risk for voice disorders. The vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises help to prevent voice problems and injuries to the vocal folds in the voice of professional users [4, 11]. This study was conducted to explore the effect of VWCE on the acoustic characteristics in SLPs. The results showed that all outcome measures improved after 18 sessions of VWCE.

The results showed that jitter significantly decreased after the end of the 9th session and after the end of the 18th session of the exercises program. The results of the current study implied that the VWCE may reduce the vocal fold mass, stiffness, and strain. The improvement in voice quality due to VWCE was evident in the jitter. The results of this study followed by the study of Amir et al., their study examined the effect of vocal warm-up exercises in one day [11]. These results are consistent with the previous studies, in which jitter was decreased after VWCE [1]. Duration and content of the VWCE probably have caused stability in the fundamental frequency, fluency of speech, and reduction in the jitter. This study demonstrated the moderate effect sizes of jitter after the end of the intervention.

The results of this study showed that shimmer significantly decreased after the end of the 18th session of VWCE; however, shimmer significantly decreased at T1. The results of this study indicated that VWCE may not be able to reduce the shimmer. Maybe the breathing exercise is required to reach more favorable outcomes [15]. This study demonstrated the small effect sizes of shimmer after the end of the exercises program. The results of this study were similar to the study conducted by Amir et al. in 2005. Their study also reported a reduction in shimmer [11].

The results of the current study showed that HNR significantly increased after the end of the 18th session. However, the HNR significantly decreased at T1. Similar results were observed in a study with singers, in which the singers were submitted to vocal warm-up exercises [11]. Research has shown improved HNR. This result can be due to increased coordination of respiratory and phonatory [13]. This study demonstrated the small effect sizes of HNR after the end of exercise program.

The main limitation of this study was the small sample size. Future studies with larger sample sizes are therefore needed. Also, a clinical trial is suggested to investigate the effects of the VWCE combined with breathing exercises on the acoustic characteristics.

Conclusion

This pilot study was conducted to investigate the acoustic characteristics of speech and language pathologists after providing voice warm-up and cool-down exercises. Among the measured parameters, jitter had more changes and significantly decreased during the warm-up and cool-down exercises. The results demonstrated that vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises were effective in improving acoustic characteristics in speech and language pathologists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Human Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (Code: IR.REC.1396.9411360001).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Supervision: Fariba Iranpour and Leila Ghelichi; Investigation, Writing-review & editing: Fariba Iranpour and Leila Ghelichi; Writing-original draft: Fariba Iranpour; Funding acquisition, Resources: Fariba Iranpour.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Voice performance is a fundamental process that has a critical impact on people’s daily communication and professional lives [1, 2]. Professional voice users are considered as a group at risk of voice disorder [1, 2]. Speech and language pathologists (SLPs) are professional voice users who use their voices for therapy, counseling, conferencing, and public speaking that goes beyond ordinary daily conversations [3, 4]. According to Gottliebson et al., the prevalence of voice disorders in speech and language pathologist students was 12% [3]. Several studies showed that vocal problems, such as fatigue, hoarseness, irritation in the larynx, low pitch, breathiness, straining, frequency breaks, and resonance changes are prevalent in SLPs [3, 4].

The vocal training method includes three main approaches to prevent voice problems. The direct approach comprises of vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises (VWCE). The indirect approach includes vocal hygiene council and the third approach is a combination of direct and indirect strategies [4-6]. The vocal warm-up exercises affect the acoustic characteristics by increasing blood flow to the vocal fold muscles, reducing muscle viscosity, and decreasing fatigue [1, 5]. The vocal cool-down exercises lead to faster recovery time and return the speaking voice to normal more quickly [1, 7]. Studies conducted on the singers indicated that the VWCE improves vibrato characteristics due to improved vocal quality [1 7-11]. Santos et al. examined the difference in the impact of direct and indirect approaches on SLP and audiology students. They reported that the direct approach, including the VWCE, led to significant improvement in the voice quality [4]. Van Lierde et al. in a study on female students training for SLPs showed that warming up the vocal mechanism is beneficial to the objective vocal quality and the vocal performance in future SLPs [5]. A dearth of published studies investigates the effect of VWCE on SLPs with clinical activity. Therefore, this study was conducted to explore the effect of vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises on the acoustic characteristics of SLPs.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study to evaluate the effects of the VWCE on SLPs. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS). The consent form was obtained from all SLPs before taking part in the study.

Study participants

Eighteen participants were recruited from the School of Rehabilitation Sciences, IUMS. The inclusion criteria included age between 25-50 years, having at least 10 hours of clinical activity in a week, participants must have at least one year of clinical work experience, having no history of using effective drugs on the voice such as steroids, no history of pathological voice disorder and problems in hearing, neurological, velopharyngeal, and laryngological disorders, all the subjects were non-smoker and were aware and compliance with the vocal hygiene behavior. The exclusion criteria included reluctance to continue to collaborate in research.

Exercise program

The exercise program included VWCE. All the participants received 18 sessions of the exercise program, three times a week, every other day. The vocal warm-up exercises were performed for 10 minutes before clinical activity and the vocal cool-down exercises were performed for 10 minutes after clinical activity. The VWCE were included:

Lip and tongue trill. Production of the trill balances resonance, amplifies normal laryngeal tension, enhances coordination of respiration/phonation/articulation, and helps to reduce pharyngeal squeezing [12, 13].

Humming is used to achieve an improved balance of oronasal resonance and relaxes the articulations, and optimizes nasal resonance [12, 13].

Sigh and yawn, this technique moves the tongue forward and reduces extrinsic laryngeal muscle tension. Easy, natural airflow and phonation are fosters [12, 13].

Outcome measures

In this study, the acoustic characteristics including jitter, shimmer, and harmonic-to-noise rate (HNR) were used as outcome measures. These acoustic characteristics were measured before the exercise program (T0), after the end of the 9th session (T1), and after the end of the 18th session (T2).

Acoustic assessment

The Praat software, version 5.3.8.1 was used to extract the acoustic voice characteristics. The first and the last second of vocal samples were eliminated due to natural instability. The remaining second was analyzed.

Voice recording

The voice sample was recorded with a microphone coupled to a Zoom Corporation H5 Handy Recorder (4-4-3 Surugadai, Kanda, Chiyoda-ku,Tokyo 101-0062 Japan) at a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz and 16 bits, stored in the wav format. The microphone was placed at a distance of 5 cm from the mouth of the participants with an angle of 45 degrees and in a setting position. The procedure was performed in a silent room with noise kept below 40 dB. The vowel /a/ was sustained three times for 3 s in participation’s habitual frequency and intensity of speech.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 21. Descriptive (Mean±SE) and inferential analyses were performed for statistical data analysis. To analyze the normality of data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. One-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the effect of the VWCE on the outcome measures with time before the exercise program (T0), after the end of the 9th session (T1), after the end of the 18th session (T2) as the within-subject variable and then a Bonferroni adjustment test followed for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) of the changed scores were calculated to determine the treatment effects. The effect sizes were defined as <0.20 (negligible), between ≥0.20 and <0.50 (small), between ≥0.50 and <0.80 (moderate), and ≥0.80 (large) [14]. P≤0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 18 participants (5 men, 13 women) with a Mean±SD age of 28.5±4.5 years were included in the study. The Mean±SD clinical activity of the SLPs was 26.56±10.9 hours per week. Table 1 presents the details of the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Jitter

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant decreases in the jitter after the VWCE. Bonferroni test indicated significant decreases at T1 and T2 compared to T0 (P<0.05). The jitter at T2 similar to that at T1 (P<0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was violated, the greenhouse Geisser correction was used. For the adjusted values, F(1.18, 0.10)=11.509, P<0.001. A moderate effect size was found for the jitter (d=0.61) (Table 2).

Shimmer

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant decreases in the shimmer after the VWCE. Bonferroni test showed significant decreases in T2 compared to T0 (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in T1 compared to T0 and T2 (P>0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was accepted, the Sphericity Assumed was used. For the adjusted values, F(2, 1.660)=4.949, P>0.05. A small effect size was found for shimmer (d=0.23) (Table 2).

Harmonic-to-noise rate (HNR)

Repeated measures ANOVA showed significant increases in the HNR after the VWCE. Bonferroni test indicated a significant increase at T2 compared to T0 and T1 (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in T1 compared to T0 (P>0.05). Since Mauchley’s test of sphericity was accepted, the assumed Sphericity was used. For the adjusted values, F(2.000, 36.677)=12.163, P>0.05. The small effect sizes were found for HNR (d=0.21) (Table 2).

Discussion

The SLPs are professional voice users who are at high risk for voice disorders. The vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises help to prevent voice problems and injuries to the vocal folds in the voice of professional users [4, 11]. This study was conducted to explore the effect of VWCE on the acoustic characteristics in SLPs. The results showed that all outcome measures improved after 18 sessions of VWCE.

The results showed that jitter significantly decreased after the end of the 9th session and after the end of the 18th session of the exercises program. The results of the current study implied that the VWCE may reduce the vocal fold mass, stiffness, and strain. The improvement in voice quality due to VWCE was evident in the jitter. The results of this study followed by the study of Amir et al., their study examined the effect of vocal warm-up exercises in one day [11]. These results are consistent with the previous studies, in which jitter was decreased after VWCE [1]. Duration and content of the VWCE probably have caused stability in the fundamental frequency, fluency of speech, and reduction in the jitter. This study demonstrated the moderate effect sizes of jitter after the end of the intervention.

The results of this study showed that shimmer significantly decreased after the end of the 18th session of VWCE; however, shimmer significantly decreased at T1. The results of this study indicated that VWCE may not be able to reduce the shimmer. Maybe the breathing exercise is required to reach more favorable outcomes [15]. This study demonstrated the small effect sizes of shimmer after the end of the exercises program. The results of this study were similar to the study conducted by Amir et al. in 2005. Their study also reported a reduction in shimmer [11].

The results of the current study showed that HNR significantly increased after the end of the 18th session. However, the HNR significantly decreased at T1. Similar results were observed in a study with singers, in which the singers were submitted to vocal warm-up exercises [11]. Research has shown improved HNR. This result can be due to increased coordination of respiratory and phonatory [13]. This study demonstrated the small effect sizes of HNR after the end of exercise program.

The main limitation of this study was the small sample size. Future studies with larger sample sizes are therefore needed. Also, a clinical trial is suggested to investigate the effects of the VWCE combined with breathing exercises on the acoustic characteristics.

Conclusion

This pilot study was conducted to investigate the acoustic characteristics of speech and language pathologists after providing voice warm-up and cool-down exercises. Among the measured parameters, jitter had more changes and significantly decreased during the warm-up and cool-down exercises. The results demonstrated that vocal warm-up and cool-down exercises were effective in improving acoustic characteristics in speech and language pathologists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Human Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (Code: IR.REC.1396.9411360001).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Supervision: Fariba Iranpour and Leila Ghelichi; Investigation, Writing-review & editing: Fariba Iranpour and Leila Ghelichi; Writing-original draft: Fariba Iranpour; Funding acquisition, Resources: Fariba Iranpour.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Onofre F, Prado YA, Rojas GVE, Garcia DM, Aguiar-Ricz L. Measurements of the acoustic speaking voice after vocal warm-up and cooldown in choir singers. Journal of Voice. 2017; 31(1):129.e9-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2015.12.004] [PMID]

- Van Lierde KM, D'haeseleer E, Wuyts FL, De Ley S, Geldof R, De Vuyst J, et al. The objective vocal quality, vocal risk factors, vocal complaints, and corporal pain in Dutch female students training to be speech-language pathologists during the 4 years of study. Journal of Voice. 2010; 24(5):592-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2008.12.011] [PMID]

- Gottliebson RO, Lee L, Weinrich B, Sanders J. Voice problems of future speech-language pathologists. Journal of Voice. 2007; 21(6):699-704. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.07.003] [PMID]

- Santos AC, Borrego MC, Behlau M. [Effect of direct and indirect voice training in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology students (English, Portuguese)]. Codas. 2015; 27(4):384-91. [DOI:10.1590/2317-1782/20152014232] [PMID]

- Van Lierde KM, D'haeseleer E, Baudonck N, Claeys S, De Bodt M, Behlau M. The impact of vocal warm-up exercises on the objective vocal quality in female students training to be speech language pathologists. Journal of Voice. 2011; 25(3):e115-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.11.004] [PMID]

- Rodríguez-Parra MJ, Adrián JA, Casado JC. Comparing voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene treatments in dysphonia using a limited multidimensional evaluation protocol. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2011; 44(6):615-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.07.003] [PMID]

- Ragan K. The impact of vocal cool-down exercises: A subjective study of singers' and listeners' perceptions. Journal of Voice. 2016; 30(6):764.e1-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2015.10.009] [PMID]

- Moorcroft L, Kenny DT. Singer and listener perception of vocal warm-up. Journal of Voice. 2013; 27(2):258.e1-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.12.001] [PMID]

- Motel T, Fisher KV, Leydon C. Vocal warm-up increases phonation threshold pressure in soprano singers at high pitch. Journal of Voice. 2003; 17(2):160-7. [DOI:10.1016/S0892-1997(03)00003-1] [PMID]

- Mezzedimi C, Spinosi MC, Massaro T, Ferretti F, Cambi J. Singing voice: Acoustic parameters after vocal warm-up and cool-down. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology. 2020; 45(2):57-65. [DOI:10.1080/14015439.2018.1545865] [PMID]

- Amir O, Amir N, Michaeli O. Evaluating the influence of warmup on singing voice quality using acoustic measures. Journal of Voice. 2005; 19(2):252-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.02.008] [PMID]

- Boone DR. The voice and voice therapy. Bloomington: Pearson; 2010. [Link]

- Colton RH, Casper JK, Leonard R. Understanding voice problems: A physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Link]

- Middel B, van Sonderen E. Statistical significant change versus relevant or important change in (quasi) experimental design: Some conceptual and methodological problems in estimating magnitude of intervention-related change in health services research. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2002; 2:e15. [DOI:10.5334/ijic.65] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Raphael LJ, Borden GJ, Harris KS. Speech science primer: Physiology, acoustics, and perception of speech. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Link]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Speech Therapy

Received: 2023/12/1 | Accepted: 2024/12/24 | Published: 2023/12/30

Received: 2023/12/1 | Accepted: 2024/12/24 | Published: 2023/12/30