Volume 6, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2023)

Func Disabil J 2023, 6(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahbazi M, Karamali Esmaeili S. Application of the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) in Psychosocial Needs of Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: A Case Study. Func Disabil J 2023; 6 (1) : 274.1

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-235-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-235-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,esmaeili.s@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 928 kb]

(5111 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1764 Views)

Evaluation based on model of MOHO concepts

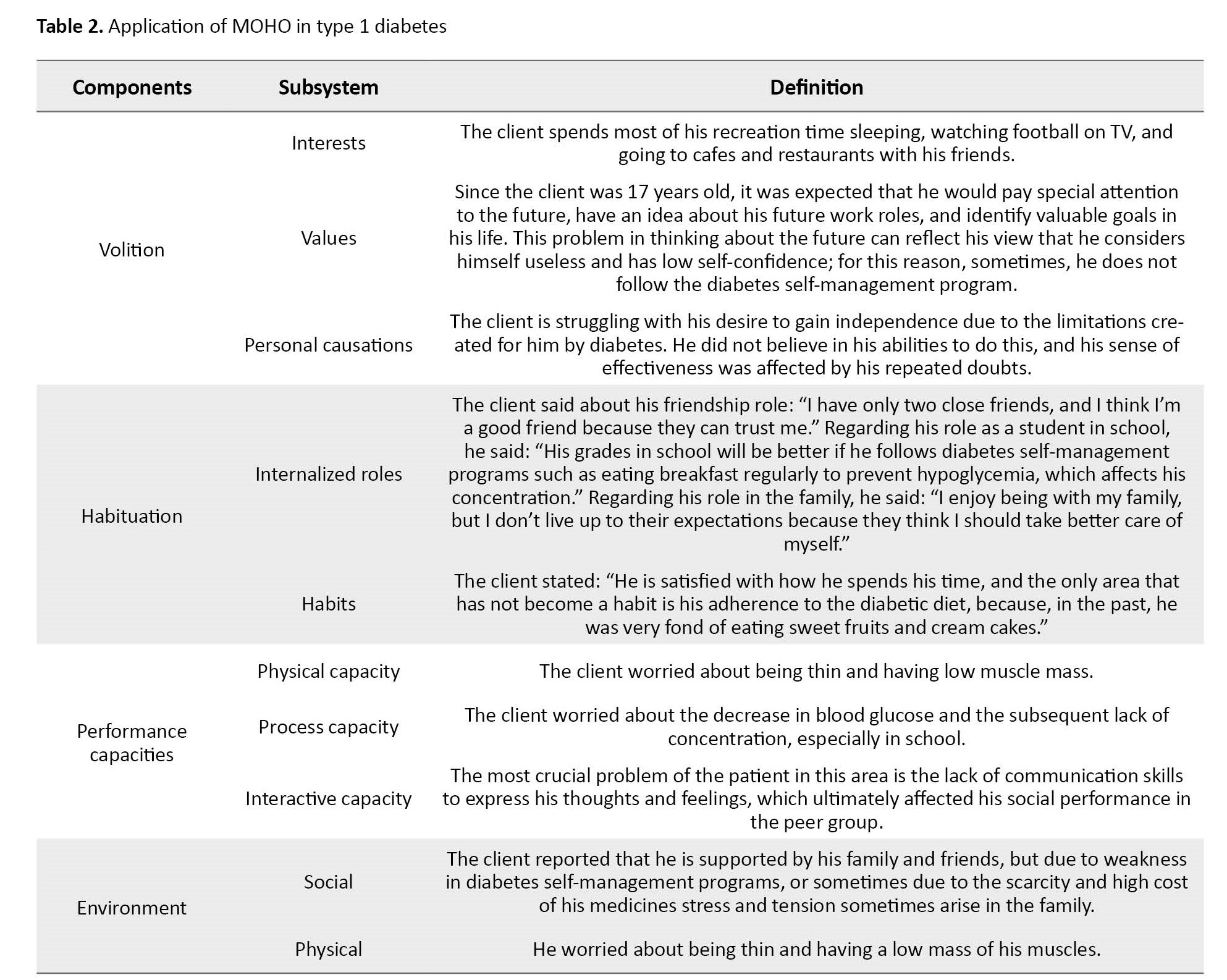

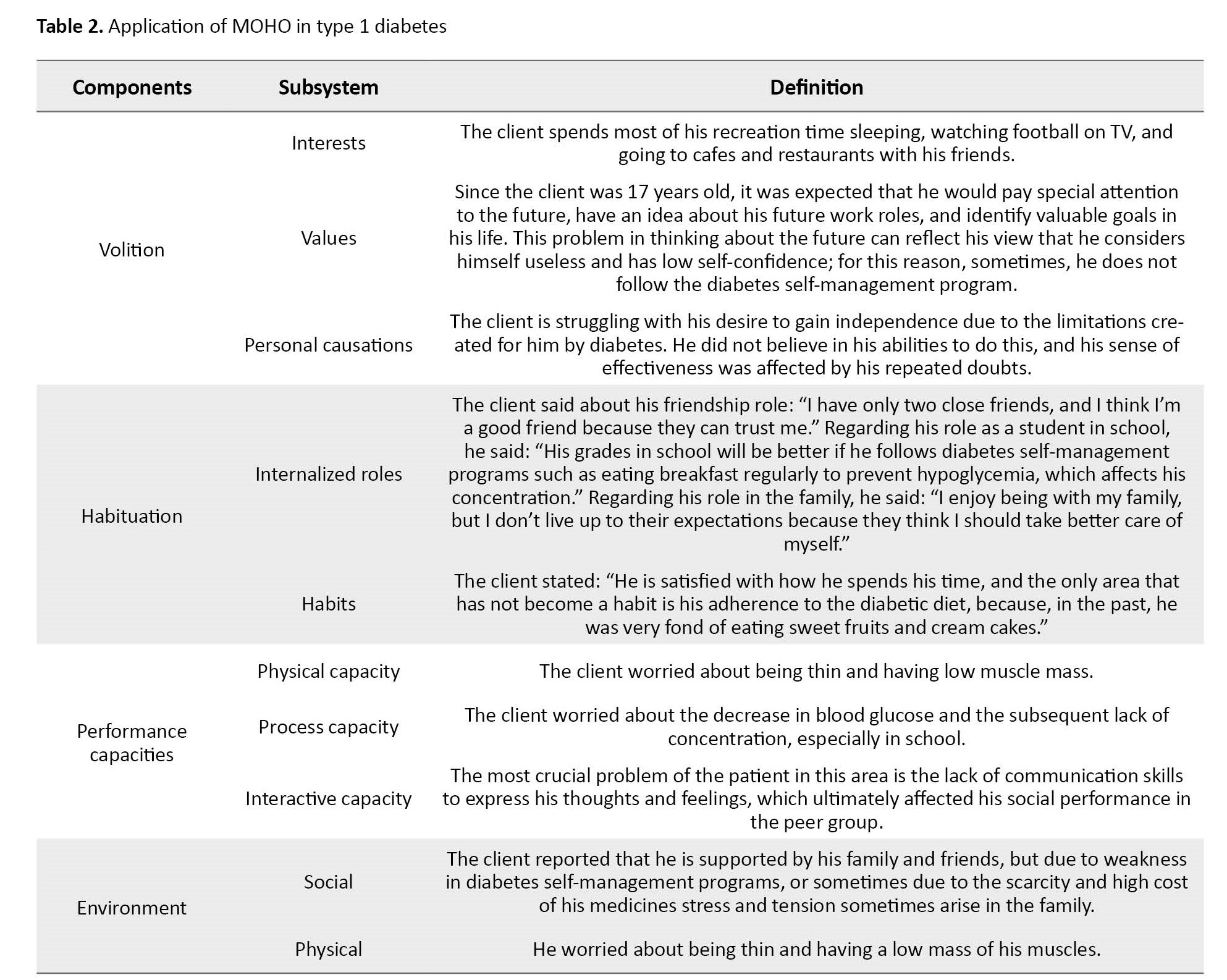

Sometimes, he is not involved in diabetes self-management activities (for example, he does not want to eat fruits and low-fat dairy products). Also, the client was hospitalized twice for 4 to 6 hours due to nausea, severe thirst, and increased edema in the legs. Table 2 presents the application of MOHO in type 1 diabetes.

Occupational therapy programming

The first focus of treatment for the client was to help him adhere to his diabetic diet. For this purpose, it was necessary to use mobile phone applications, such as “Fereshte Salamat” to provide a list of meals that specifies the required ratio of protein, fat, and carbohydrates in each meal. To fixation on self-management behaviors in patients with diabetes, researchers have emphasized the need to integrate these behaviors into their daily life habits to increase their sense of control and mastery over their living conditions, which requires frequent activities in a fixed environment [9], therefore occupational therapist used telephone follow-up to ensure the client’s adherence to the self-management programs. Finally, this person’s healthcare provider suggested holding a peer group to address his psychosocial needs and behavioral changes.

Discussion

Numerous studies showed that psychosocial support is essential to managing the daily challenges of diabetes [13]. For many patients, living with diabetes is a complex, lifelong process that the psychological consequences of constant self-management and pressure from family, friends, and healthcare professionals can increase the stress in the daily lives of people with diabetes. Therefore, people with diabetes must develop many skills that help them redesign their lifestyle. Scientific evidence has shown that occupational therapists can provide interventions that facilitate psychosocial adjustment to diabetes, thereby improving their ability to self-management [14]. Considering the comprehensiveness of MOHO, using this model, therapists are assured that they are working correctly. However, since the MOHO was developed and known in the 1980s, many occupational therapists may have graduated before the introduction of this model and may not be familiar with the concept of MOHO, therefore it may not be used in practice. In this sense, strengthening relationships between clinical specialists and scientists by creating an association to use the model, organizing regular training, and sharing experiences will lead to the use of MOHO, and strengthening the sense of belonging to this profession [15, 16].

Conclusion

In adolescents with type 1 diabetes, the volition, habituation, and performance capacity are affected by disability. Therefore designing and structuring goals and treatment based on MOHO can help therapists to increase the meaningfulness and purposefulness of their treatment by using a model.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mehraban, Dr. Karamali Esmaili and Dr. Amini for their guidance for the clinical and research use of occupational therapy models.

References

Full-Text: (1156 Views)

Introduction

Diabetes has become one of the most prominent and common chronic diseases of our time, causing life-threatening, disabling, and costly complications and shortening life expectancy. The hallmark of this disorder is impaired insulin secretion and action, or both. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are the leading and vital forms of this disease. The most common form of diabetes in children and adolescents is type 1 diabetes, which leads to insufficient or almost complete insulin deficiency [1].

The incidence of diabetes in adolescents has increased over the last decade [2]. Metabolic control and dietary adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes are lower than in preadolescent children, which may be related to physical changes and psychological and social problems at this stage of life [3]. Young people described difficulties in providing independent care and increasing conflict between parents, including fear of needles, forgetting to take insulin, feelings of shame, and the belief that diabetes was a burden on their lives. Additionally, it is difficult to balance multiple family, school, and work responsibilities while dealing with a chronic illness in adolescence [4]. Currently, the world spends a lot of money to control diabetes. Therefore, it is necessary to find effective ways to manage diabetes to reduce the risk of subsequent complications and the economic burden [5].

One of the treatment strategies relies on the patient’s ability to perform self-management activities continuously [6]. Self-management refers to care that includes all intentional actions aimed at caring for a person’s physical, mental, and emotional health. Self-management practices include diet, exercise, medications, emotions, sleep, and medical care. In other words, self-management integrates diabetes into daily life to make diabetes ‘part of me’ and move the Journey towards independence [7].

The unique role of occupational therapists in diabetes care is recognized for their contribution to improving adherence and self-management skills, mentioned as an aspect of health management in the occupational therapy practice framework [8], which aims to maximize people’s ability to carry out tasks that require them during daily life [9, 10]. To achieve this goal, comprehensive models, such as the model of human occupation (MOHO) are practical. This case report aims to review the constructs and propositions of MOHO with a focus on its potential application in occupational therapy practice with type 1 diabetes.

Case Presentation

Background information about the participant

This case report is about a 17-year-old boy who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 14 years, and his uncle also has a family history of type 1 diabetes. His anthropometric data are as follows, his weight is 60 kg, and his height is 175 cm (body mass index [BMI]: 60/(1.75)2=19.60). He lives with his parents and his 10-year-old sister.

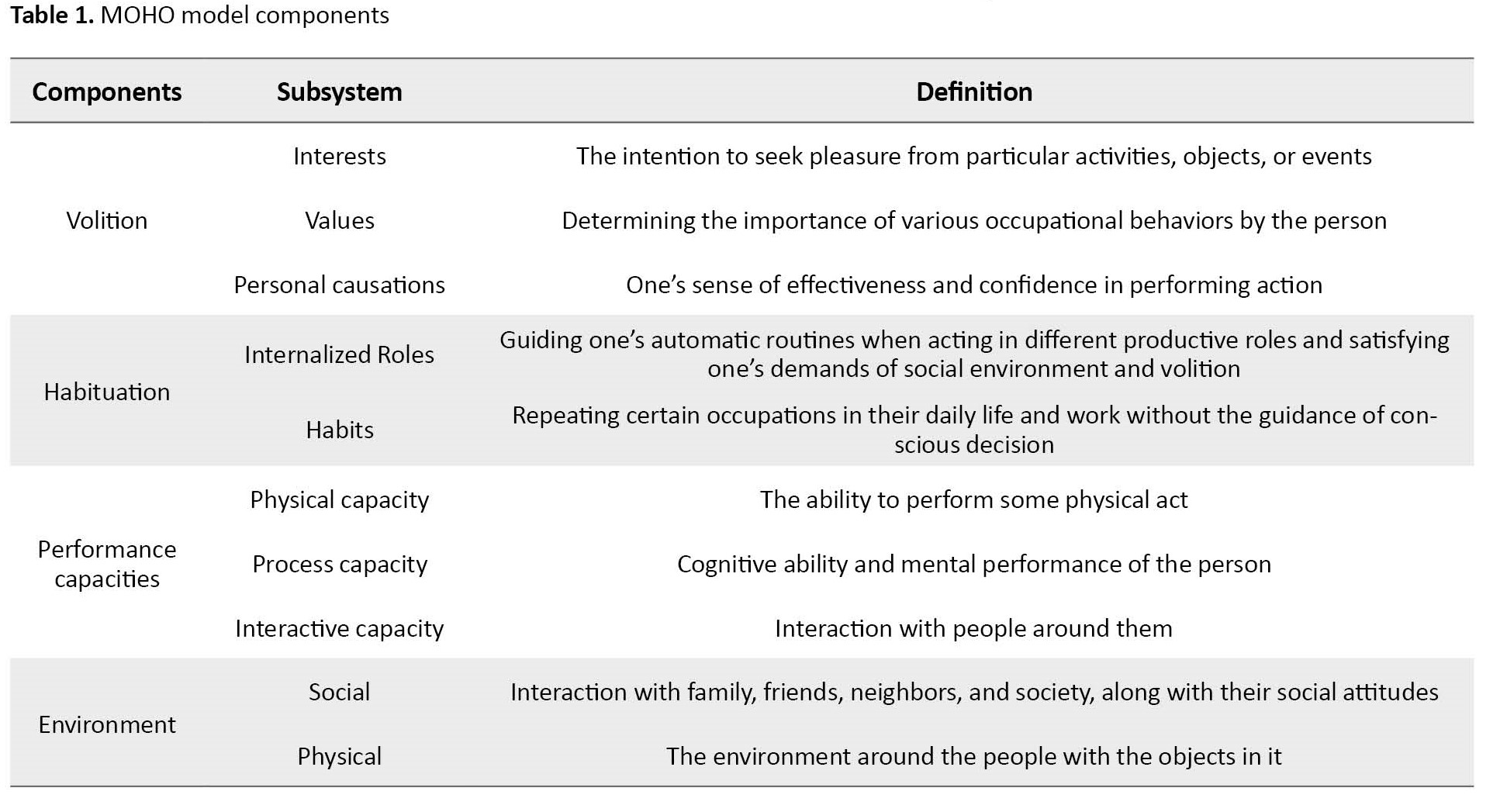

Structures of MOHO

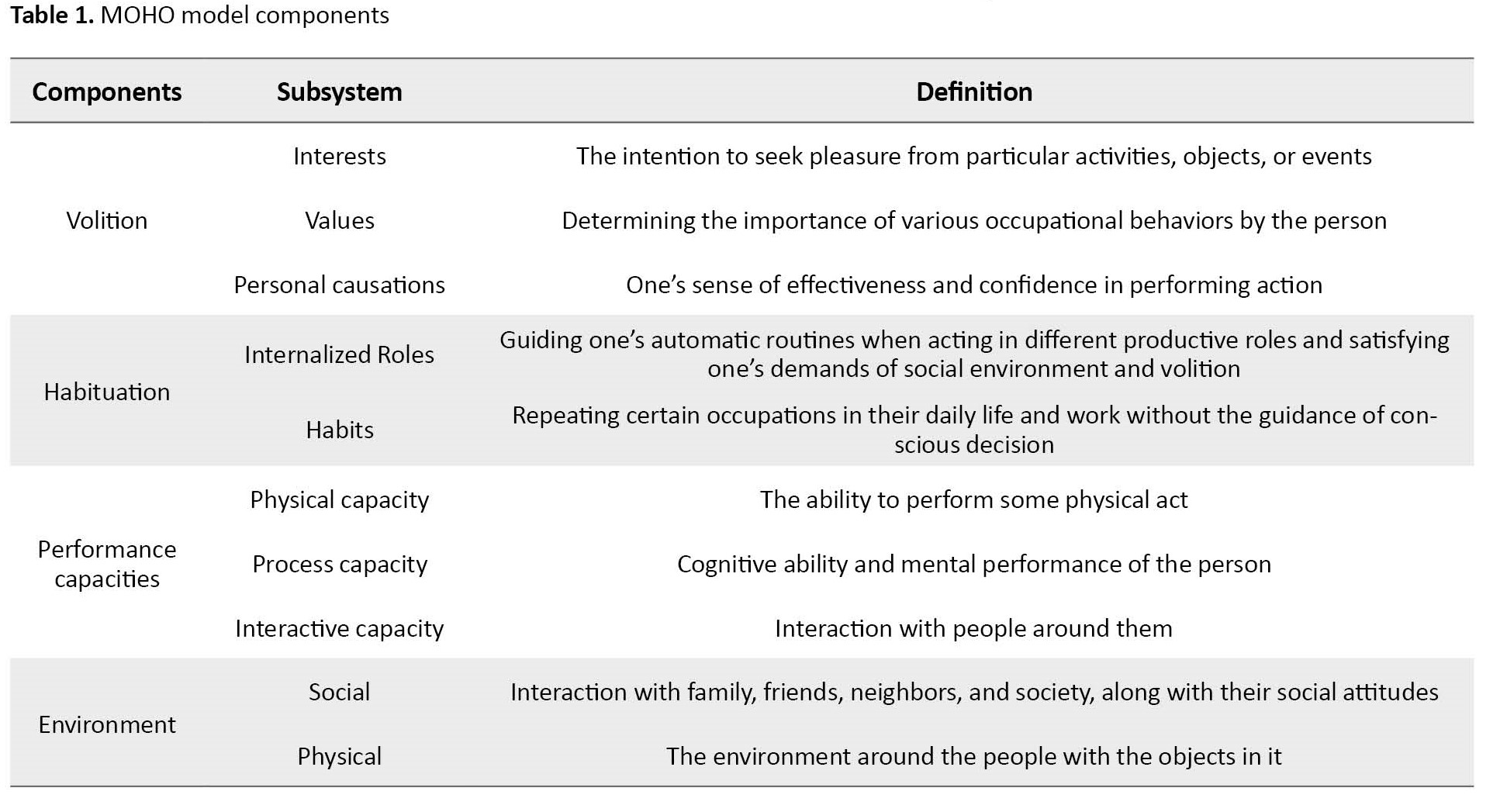

MOHO was developed by Kielhofner in the 1980s. This model considers the human being as a system entity whose occupations are influenced by three subsystems “volition”, “habituation”, and “performance capacity”, which is also in moment interaction with the environment [11]. To view the components of this model and their definitions, refer to Table 1.

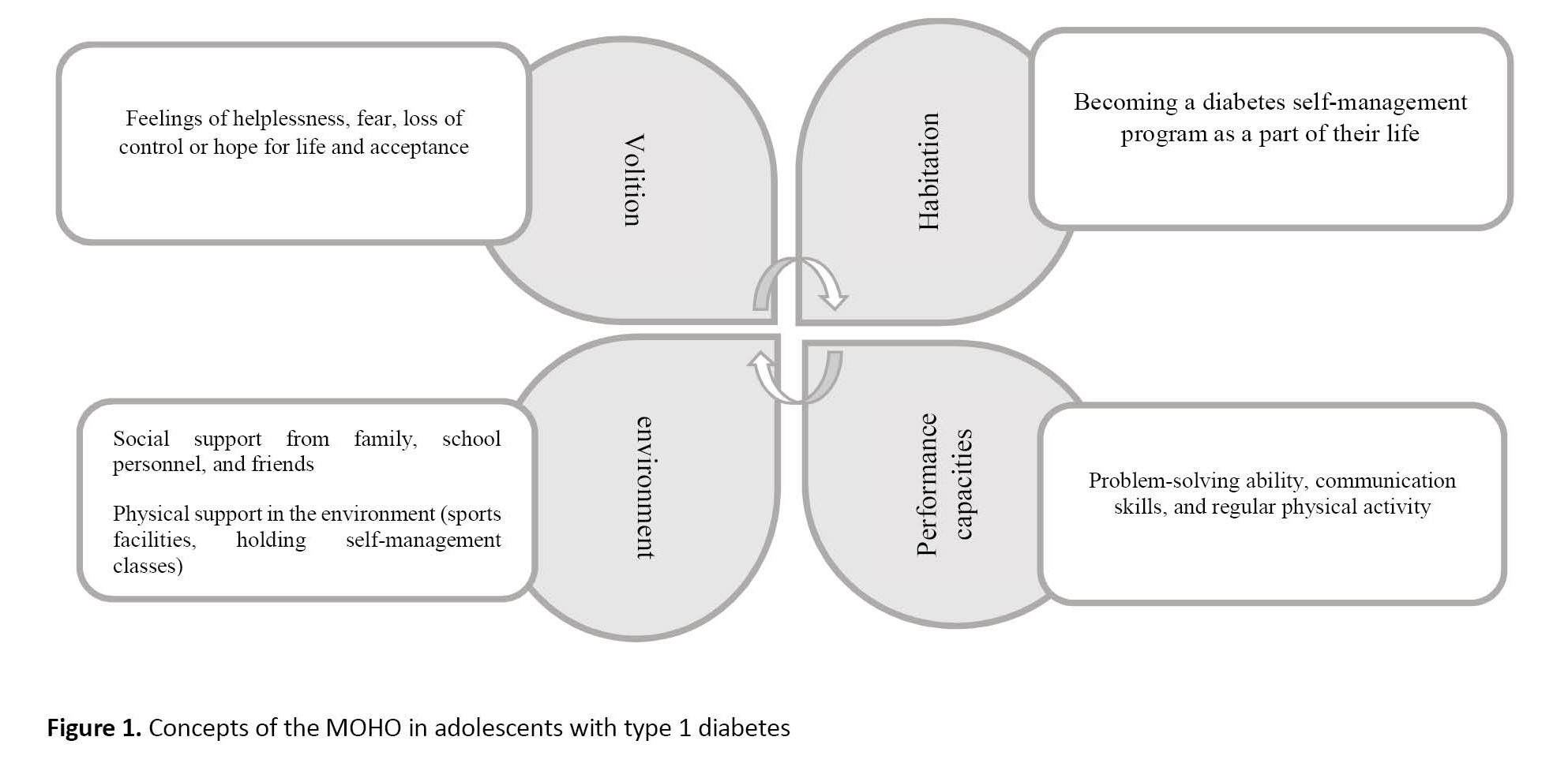

In the following, the concepts of this model are defined in adolescents with diabetes.

Volition

Adolescents’ thoughts and feelings about occupations motivate them to do so. In MOHO, these thoughts and feelings are divided into interest, value, and personal causation. These three factors motivate a person to anticipate, select, experience, and interpret an occupation [11].

Personal causations

Managing diabetes requires learning new skills, e.g. healthy eating, following treatments, monitoring blood glucose levels, and regular exercise. Therefore, due to the sensitivity of adolescence in shaping a person’s future and the need for self-efficacy in diabetes self-management (without direct parental involvement), many people experience a sense of fear and loss of control [12].

Values and interests

The values and interests of adolescents with diabetes influence their motivation to participate in self-management activities. Faith and religious beliefs, interest in life, trying to deal rationally with problems, and tolerance in accepting situations increase patients’ ability to deal with issues, such as illness [12].

Habitation

Habituation is the organization of actions into patterns and routines governed by habits and roles. Therefore, depending on the context, every person implements specific behavioral patterns in daily life [11].

Internalized roles

The adolescent’s roles are influenced by his diabetes. In the family role, for example, the family’s nutritional plan may change because the young person has to adhere to a particular diet. As a student, a person stands out from your peers by eating special snacks and going to the toilet frequently. In the role of a friend, one may hide the need for insulin injections to avoid being labeled as different [12].

Habits

Once a person is diagnosed with diabetes, their lifestyle changes. Controlling this disease requires implementing self-management programs (daily exercise, monitoring blood glucose at certain times of the day, daily insulin injections, and avoiding excessive consumption of sweets and snacks) so that they become part of their identity and routine [12].

Performance capacities

Performance capacities are influenced by an individual’s underlying physical and mental abilities and how these abilities are used and experienced [11]. Adolescence is a time of great stress regarding being perfect and equal to others. When young people with diabetes can accept the difference that disease has made to them, they can adapt to their condition. Many solutions can help these people. The vital issue is problem-solving to determine the correct insulin unit and regular physical activity. In addition, one of the critical factors for success in diabetes self-management is the ability to share one’s problems with the people around us, especially peers, rather than hiding from them [12].

Environment

From a MOHO perspective, the environment can significantly influence occupational behavior. The environment affects motivation, organization, and professional performance. The environment includes contextual characteristics, such as physical, social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics. MOHO assumes that a person’s environment and internal characteristics are interconnected and influence occupational behavior [11]. For adolescents with diabetes family and school are the most critical environments that affect the management of disease and functioning. Regarding the physical environment, they may point to a lack of sports facilities, self-management training classes in public health centers, and economic factors affecting insulin supply. In the social environment, social support from family, friends, and school staff can be mentioned in implementing self-management programs [12]. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the concepts of the MOHO model in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Diabetes has become one of the most prominent and common chronic diseases of our time, causing life-threatening, disabling, and costly complications and shortening life expectancy. The hallmark of this disorder is impaired insulin secretion and action, or both. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are the leading and vital forms of this disease. The most common form of diabetes in children and adolescents is type 1 diabetes, which leads to insufficient or almost complete insulin deficiency [1].

The incidence of diabetes in adolescents has increased over the last decade [2]. Metabolic control and dietary adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes are lower than in preadolescent children, which may be related to physical changes and psychological and social problems at this stage of life [3]. Young people described difficulties in providing independent care and increasing conflict between parents, including fear of needles, forgetting to take insulin, feelings of shame, and the belief that diabetes was a burden on their lives. Additionally, it is difficult to balance multiple family, school, and work responsibilities while dealing with a chronic illness in adolescence [4]. Currently, the world spends a lot of money to control diabetes. Therefore, it is necessary to find effective ways to manage diabetes to reduce the risk of subsequent complications and the economic burden [5].

One of the treatment strategies relies on the patient’s ability to perform self-management activities continuously [6]. Self-management refers to care that includes all intentional actions aimed at caring for a person’s physical, mental, and emotional health. Self-management practices include diet, exercise, medications, emotions, sleep, and medical care. In other words, self-management integrates diabetes into daily life to make diabetes ‘part of me’ and move the Journey towards independence [7].

The unique role of occupational therapists in diabetes care is recognized for their contribution to improving adherence and self-management skills, mentioned as an aspect of health management in the occupational therapy practice framework [8], which aims to maximize people’s ability to carry out tasks that require them during daily life [9, 10]. To achieve this goal, comprehensive models, such as the model of human occupation (MOHO) are practical. This case report aims to review the constructs and propositions of MOHO with a focus on its potential application in occupational therapy practice with type 1 diabetes.

Case Presentation

Background information about the participant

This case report is about a 17-year-old boy who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 14 years, and his uncle also has a family history of type 1 diabetes. His anthropometric data are as follows, his weight is 60 kg, and his height is 175 cm (body mass index [BMI]: 60/(1.75)2=19.60). He lives with his parents and his 10-year-old sister.

Structures of MOHO

MOHO was developed by Kielhofner in the 1980s. This model considers the human being as a system entity whose occupations are influenced by three subsystems “volition”, “habituation”, and “performance capacity”, which is also in moment interaction with the environment [11]. To view the components of this model and their definitions, refer to Table 1.

In the following, the concepts of this model are defined in adolescents with diabetes.

Volition

Adolescents’ thoughts and feelings about occupations motivate them to do so. In MOHO, these thoughts and feelings are divided into interest, value, and personal causation. These three factors motivate a person to anticipate, select, experience, and interpret an occupation [11].

Personal causations

Managing diabetes requires learning new skills, e.g. healthy eating, following treatments, monitoring blood glucose levels, and regular exercise. Therefore, due to the sensitivity of adolescence in shaping a person’s future and the need for self-efficacy in diabetes self-management (without direct parental involvement), many people experience a sense of fear and loss of control [12].

Values and interests

The values and interests of adolescents with diabetes influence their motivation to participate in self-management activities. Faith and religious beliefs, interest in life, trying to deal rationally with problems, and tolerance in accepting situations increase patients’ ability to deal with issues, such as illness [12].

Habitation

Habituation is the organization of actions into patterns and routines governed by habits and roles. Therefore, depending on the context, every person implements specific behavioral patterns in daily life [11].

Internalized roles

The adolescent’s roles are influenced by his diabetes. In the family role, for example, the family’s nutritional plan may change because the young person has to adhere to a particular diet. As a student, a person stands out from your peers by eating special snacks and going to the toilet frequently. In the role of a friend, one may hide the need for insulin injections to avoid being labeled as different [12].

Habits

Once a person is diagnosed with diabetes, their lifestyle changes. Controlling this disease requires implementing self-management programs (daily exercise, monitoring blood glucose at certain times of the day, daily insulin injections, and avoiding excessive consumption of sweets and snacks) so that they become part of their identity and routine [12].

Performance capacities

Performance capacities are influenced by an individual’s underlying physical and mental abilities and how these abilities are used and experienced [11]. Adolescence is a time of great stress regarding being perfect and equal to others. When young people with diabetes can accept the difference that disease has made to them, they can adapt to their condition. Many solutions can help these people. The vital issue is problem-solving to determine the correct insulin unit and regular physical activity. In addition, one of the critical factors for success in diabetes self-management is the ability to share one’s problems with the people around us, especially peers, rather than hiding from them [12].

Environment

From a MOHO perspective, the environment can significantly influence occupational behavior. The environment affects motivation, organization, and professional performance. The environment includes contextual characteristics, such as physical, social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics. MOHO assumes that a person’s environment and internal characteristics are interconnected and influence occupational behavior [11]. For adolescents with diabetes family and school are the most critical environments that affect the management of disease and functioning. Regarding the physical environment, they may point to a lack of sports facilities, self-management training classes in public health centers, and economic factors affecting insulin supply. In the social environment, social support from family, friends, and school staff can be mentioned in implementing self-management programs [12]. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the concepts of the MOHO model in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Evaluation based on model of MOHO concepts

Sometimes, he is not involved in diabetes self-management activities (for example, he does not want to eat fruits and low-fat dairy products). Also, the client was hospitalized twice for 4 to 6 hours due to nausea, severe thirst, and increased edema in the legs. Table 2 presents the application of MOHO in type 1 diabetes.

Occupational therapy programming

The first focus of treatment for the client was to help him adhere to his diabetic diet. For this purpose, it was necessary to use mobile phone applications, such as “Fereshte Salamat” to provide a list of meals that specifies the required ratio of protein, fat, and carbohydrates in each meal. To fixation on self-management behaviors in patients with diabetes, researchers have emphasized the need to integrate these behaviors into their daily life habits to increase their sense of control and mastery over their living conditions, which requires frequent activities in a fixed environment [9], therefore occupational therapist used telephone follow-up to ensure the client’s adherence to the self-management programs. Finally, this person’s healthcare provider suggested holding a peer group to address his psychosocial needs and behavioral changes.

Discussion

Numerous studies showed that psychosocial support is essential to managing the daily challenges of diabetes [13]. For many patients, living with diabetes is a complex, lifelong process that the psychological consequences of constant self-management and pressure from family, friends, and healthcare professionals can increase the stress in the daily lives of people with diabetes. Therefore, people with diabetes must develop many skills that help them redesign their lifestyle. Scientific evidence has shown that occupational therapists can provide interventions that facilitate psychosocial adjustment to diabetes, thereby improving their ability to self-management [14]. Considering the comprehensiveness of MOHO, using this model, therapists are assured that they are working correctly. However, since the MOHO was developed and known in the 1980s, many occupational therapists may have graduated before the introduction of this model and may not be familiar with the concept of MOHO, therefore it may not be used in practice. In this sense, strengthening relationships between clinical specialists and scientists by creating an association to use the model, organizing regular training, and sharing experiences will lead to the use of MOHO, and strengthening the sense of belonging to this profession [15, 16].

Conclusion

In adolescents with type 1 diabetes, the volition, habituation, and performance capacity are affected by disability. Therefore designing and structuring goals and treatment based on MOHO can help therapists to increase the meaningfulness and purposefulness of their treatment by using a model.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mehraban, Dr. Karamali Esmaili and Dr. Amini for their guidance for the clinical and research use of occupational therapy models.

References

- Craig ME, Jefferies C, Dabelea D, Balde N, Seth A, Donaghue KC, et al. Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014; 15(Suppl 20):4-17. [DOI:10.1111/pedi.12186] [PMID]

- Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022; 183:109119. [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119] [PMID]

- Settineri S, Frisone F, Merlo EM, Geraci D, Martino G. Compliance, adherence, concordance, empowerment, and self-management: Five words to manifest a relational maladjustment in diabetes. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019; 12:299-314. [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S193752] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Babler E, Strickland CJ. Helping adolescents with type 1 diabetes figure it out. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016; 31(2):123-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2015.10.007] [PMID]

- Standl E, Khunti K, Hansen TB, Schnell O. The global epidemics of diabetes in the 21st century: Current situation and perspectives. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019; 26(2_suppl):7-14. [DOI:10.1177/2047487319881021] [PMID]

- Stephani V, Opoku D, Beran D. Self-management of diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1):1148. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-018-6050-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Carpenter R, DiChiacchio T, Barker K. Interventions for self-management of type 2 diabetes: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018; 6(1):70-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.12.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- American Occupational Therapy Association (Aota). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain & process. Bethesda: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2020. [Link]

- Pyatak EA, Carandang K, Vigen CLP, Blanchard J, Diaz J, Concha-Chavez A, et al. Occupational therapy intervention improves glycemic control and quality of life among young adults with diabetes: The resilient, empowered, active living with diabetes (real diabetes) randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41(4):696-704. [DOI:10.2337/dc17-1634] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fisher EB Jr, Delamater AM, Bertelson AD, Kirkley BG. Psychological factors in diabetes and its treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982; 50(6):993-1003. [DOI:10.1037//0022-006X.50.6.993] [PMID]

- Karamali-Esmaili S. [Model of human occupation: A review on clinical applications in rehabilitation of children (Persian)]. J Rehabil Med. 2019; 8(4):291-302. [DOI:10.22037/jrm.2019.111756.2093]

- Afshar M, Memarian R, Mohammadi E. [A qualitative Study of Teenagers' Experiences about Diabetes (Persian)]. J Diabetes Nurs. 2014; 2(1):7-19. [Link]

- Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Castle DJ, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Psychosocial interventions and wellbeing in individuals with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2017; 8:2063. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02063] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shen X, Shen X. The role of occupational therapy in secondary prevention of diabetes. Therapy in secondary prevention of diabetes. Int J Endocrinol. 2019; 2019:3424727 [DOI:10.1155/2019/3424727] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wimpenny K, Forsyth K, Jones C, Matheson L, Colley J. Implementing the model of human occupation across a mental health occupational therapy service: Communities of practice and a participatory change process. Br J Occup Ther. 2010; 73(11):507-16. [DOI:10.4276/030802210X12892992239152]

- Lee SW, Kielhofner G, Morley M, Heasman D, Garnham M, Willis S, et al. Impact of using the model of human occupation: A survey of occupational therapy mental health practitioners' perceptions. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012; 19(5):450-6. [DOI:10.3109/11038128.2011.645553] [PMID]

Type of Study: Case Study |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 2023/11/28 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2023/02/7

Received: 2023/11/28 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2023/02/7