Volume 6, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2023)

Func Disabil J 2023, 6(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Naghavi Kheslat M, Alizadeh Zarei M, Hojati Abed E. The Effect of Occupation-based Self-determination Intervention on Communication and Interaction Skills of Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Func Disabil J 2023; 6 (1) : 266.1

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-231-en.html

URL: http://fdj.iums.ac.ir/article-1-231-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,alizadeh.m@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Personal autonomy, Social participation, Adolescent, Occupational therapy, Communication, Social skill

Full-Text [PDF 1170 kb]

(602 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1218 Views)

Full-Text: (312 Views)

1. Introduction

Field and Hoffman defined self-determination as “a person’s ability to define goals and achieve them based on knowing and valuing oneself”. Their model deals with the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors that lead to self-determination and includes five components, know yourself, value yourself, plan, act, and experience outcomes and learn [1].

According to the latest study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2020, regarding the occurrence and indications of autism among 8-year-old children in eleven distinct regions across the United States, it was found that 1 out of every 36 children has autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Previous studies reported 1 in 54 children and 1 in 44 children with autism in 2016 and 2018, respectively. The prevalence figures vary significantly across various nations, with rates as low as under 0.2% in China and Italy, while South Korea reports a significantly higher rate of 2.7% [2]. The variation in autism prevalence is likely attributable to several factors, one of which is the nature of autism as a spectrum disorder, characterized by diverse traits that influence its definition [3].

In a person with ASD, the developmental process of self-determination is often hindered because the key features of this disorder may fundamentally weaken the self-determination effort [4]. Problems in executive function and adaptive behaviors are very common in autism [5]. Similarly, many adolescents with autism prefer rigid routines and feel uncomfortable in unfamiliar situations [4]. One of the key challenges faced by individuals on the spectrum is in social participation, defined as ‘involvement in a subset of activities that involve social situations with others’ [6]. Engaging in these social activities necessitates employing a collection of abilities, which occupational therapists have characterized as straightforward, easily observable actions with an inherent functional intent [7].

The diagnosis of autism requires the presence of deficiencies in both communication and social interactions. Holding a back-to-back conversation, using nonverbal communication behaviors (e.g. gestures), and developing and maintaining social relationships are certain instances of communication and interaction skills [8]. It appears reasonable to suggest that the self-determination status of students with autism can be substantially impacted by their social skills, as challenges in social interaction can constrain their ability to function independently [4]. However, in a study conducted by Lee et al. in 2021, many students with autism who participated in the study found that challenging themselves and developing social skills were crucial parts of their sense of belonging, which is one of the components of self-determination, and decided to compensate for their social communication problems using self-determination skills [9].

Promoting self-determination is vital for adolescents to achieve goals related to education, employment after education, social participation, and a better quality of life. By developing basic skills related to self-determination, adolescents are often more prepared to make decisions in life [4].

Few studies have reviewed the effect of self-determination interventions on adolescents with ASD. However, among these few studies, fewer number focus on the communication and interaction skills of these adolescents or even evaluated the outcomes with an occupational therapy-based instrument [10].

‘Assessment of communication and interaction skills (ACIS)’ is developed on the conceptual framework of the model of human occupation. According to this model, daily tasks consist of various distinct behavioral components referred to as “skills”. Skills are not considered a basic capacity. Rather, they refer to what happens during a performance. Three types of skills can be observed during job performance, motor, processing, communication, and interaction skills. Communication and interaction skills encompass visible actions employed to convey intentions and requirements, as well as organizing one’s conduct to engage with others. This conceptualization places the occupational therapists’ focus on what happens during social actions, instead of requiring them to infer it from the underlying capacity of the clients [11].

Objectives

This research aims to investigate the effect of occupation-based self-determination interventions on the communication and interaction skills of adolescent students with ASD in occupational performance level.

2. Materials and Methods

Trial design

This research is a single-blinded study, in which the assessors are blinded. This study was conducted as a randomized controlled trial in parallel groups and conducted from October 2022 to August 2023 in Tehran City, Iran. Two study groups of intervention and control were randomly assigned for the study.

Participants

This study involved male adolescent students attending an autism-specific educational complex located in Tehran City. The inclusion criteria included the students aged 13–18 years, ASD level 1 diagnosis by Gilliam autism rating scale third edition (GARS-III), and no other medical diagnosis. The exclusion criteria included the participants who had a sudden change in their medication (consuming selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]).

Setting

The research was conducted in a classroom in an autism-specific school situated in Tehran City from October 2022 to August 2023. The intervention sessions were conducted in a spacious classroom suitable for accommodating group sessions involving 7 to 10 students.

Randomization, blinding, and sample size

The study included 40 male high school students with autism, all of whom were enrolled in a specialized school for individuals with autism in Tehran City. These participants were randomized using a random-number table. The randomization process was conducted by an impartial individual who had no role in the intervention. Figure 1 shows the recruitment and participant flow throughout the trial. We determined the necessary sample size for each group by referring to previous research [12]. As a result, participants were divided into the intervention group (n=21) and the control group (n=19) through random sampling.

Procedure

At first, ACIS and demographic questionnaires were gathered from the students. All participants were assessed in pre- and post-intervention 1 week before and after intervention and follow-up (after 45 days) by a blinded assessor. To ensure adequate control and individualized attention to each participant in the intervention group, we employed random allocation, dividing them into three groups, each consisting of seven individuals. This approach is consistent with recommendations regarding group therapy group size based on available evidence [13]. The first author of the study conducted the intervention. Students in the intervention groups underwent a series of sixteen 60-minute sessions as part of the intervention program. At the beginning of each session, the participants were given clear instructions to implement the intervention plan.

Intervention program

The activities of the intervention program were tailored according to the participants’ requirements and preferences, inspired by the self-determination model proposed by Field and Hoffman [1]. The design of the intervention program included opinions from an expert panel consisting of two faculty members (of Iran University of Medical Sciences) having Ph.D.s in occupational therapy and two occupational therapists who have been working with the autism community for 10 years. Every panelist had expertise in the field of ASD. The intervention program was conducted through group sessions, comprising sixteen sessions, each lasting for 60 minutes. In each session, the participants engaged in activities related to the subject of the session. The objectives of previous sessions were reviewed at the onset of each session. The content of each session was rooted in the self-determination model proposed by Field and Hoffman. This model contains five components, including know yourself (first two sessions), value yourself (sessions 3 and 4), plan (sessions 5-7), action (sessions 8-10 and 12-15), and experience outcomes and learning (sessions 11 and 16). The participants were asked to work individually and in teams based on different tasks assigned to them, including drawing a picture of their dreams, creating a collage, making orange juice and serving it with cookies to other individuals, and preparing a salad. Meanwhile, the control group only participated in routine occupational therapy provided for every student at the school.

Instruments

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire was prepared to collect information about the age and grade of the students, their occupational therapy history, and medications.

Assessment of communication and interaction skills (ACIS)

The ACIS is an observational assessment tool specifically created to comprehensively assess an individual’s capacity for social interaction in meaningful social settings. The scale comprises 20 elements that assess communication and interaction skills, categorizing them into three theoretical domains, “physicality”, “information exchange”, and “relations”. Each element is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1–4), where a score of 1 indicates a significant deficiency leading to an unacceptable interruption in interaction, while a score of 4 indicates proficient skills that facilitate ongoing social interaction. The overall score is calculated by summing the scores of all the elements, ranging from 20 points (indicating severe deficiency) to 80 points (indicating competent performance) [11]. Kohlberg and his Swedish colleagues reviewed the psychometric properties of the test, and the evidence showed that the test has high construct validity, internal consistency, and rater reliability [14]. Keyvani et al. reviewed the translation and validity and reliability of this test in Iran [15].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of this study was divided into two main components, descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. In the descriptive section, data were presented using central indices, such as the mean, as well as measures of dispersion, such as standard deviation and standard error. To test the study hypotheses and assess the effects of time and group, we employed a combination of statistical methods. Specifically, the non-parametric chi-square test alongside parametric tests (repeated measures analysis of variance [ANOVA] and student’s t-test) was used. All statistical analyses were performed utilizing SPSS software, version 26.0.

3. Results

Initial analyses showed no significant differences in demographic characteristics among the participants (P>0.05). Table 1 presents an overview of demographic details and test scores for both groups of adolescents with ASD.

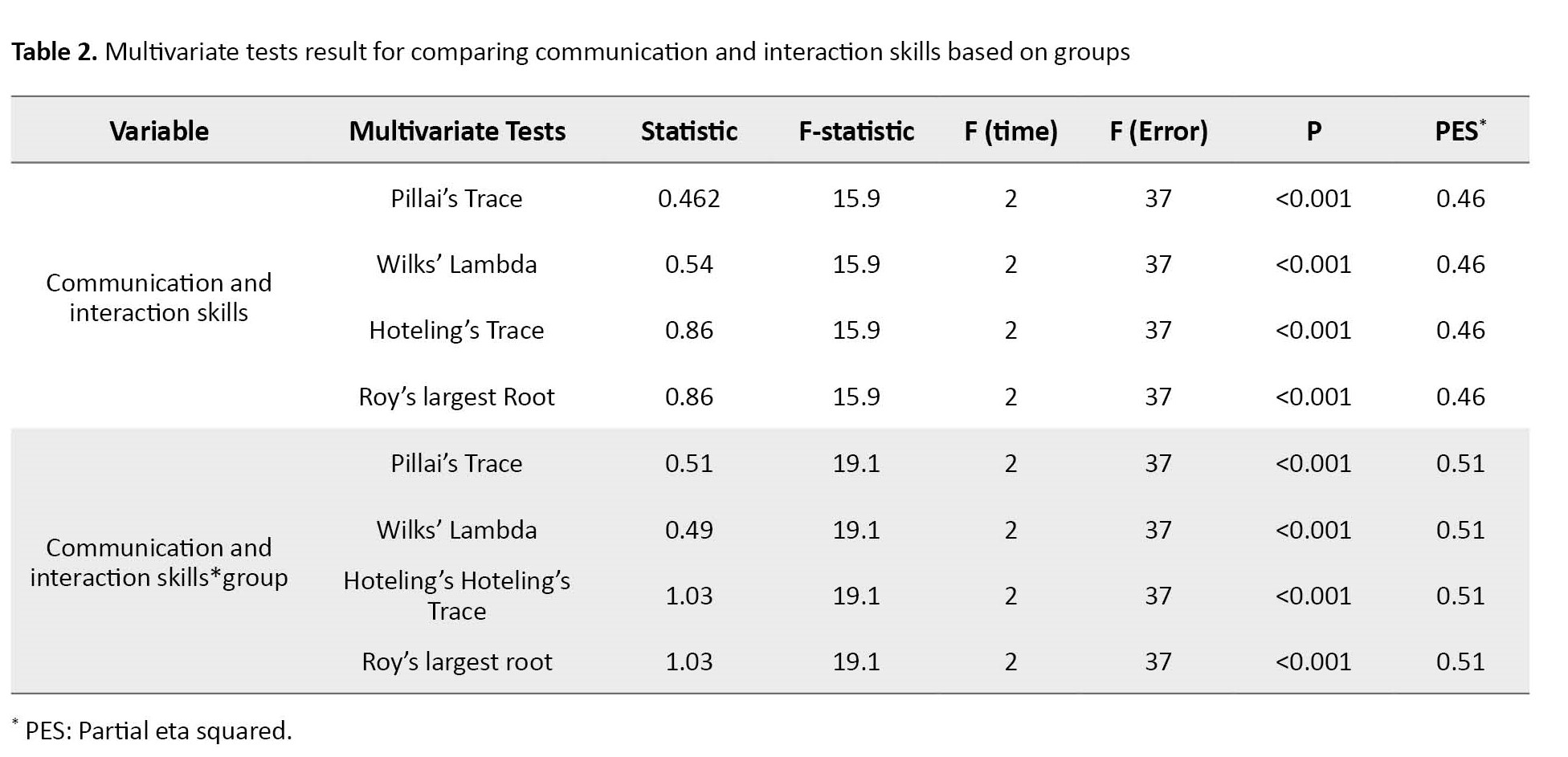

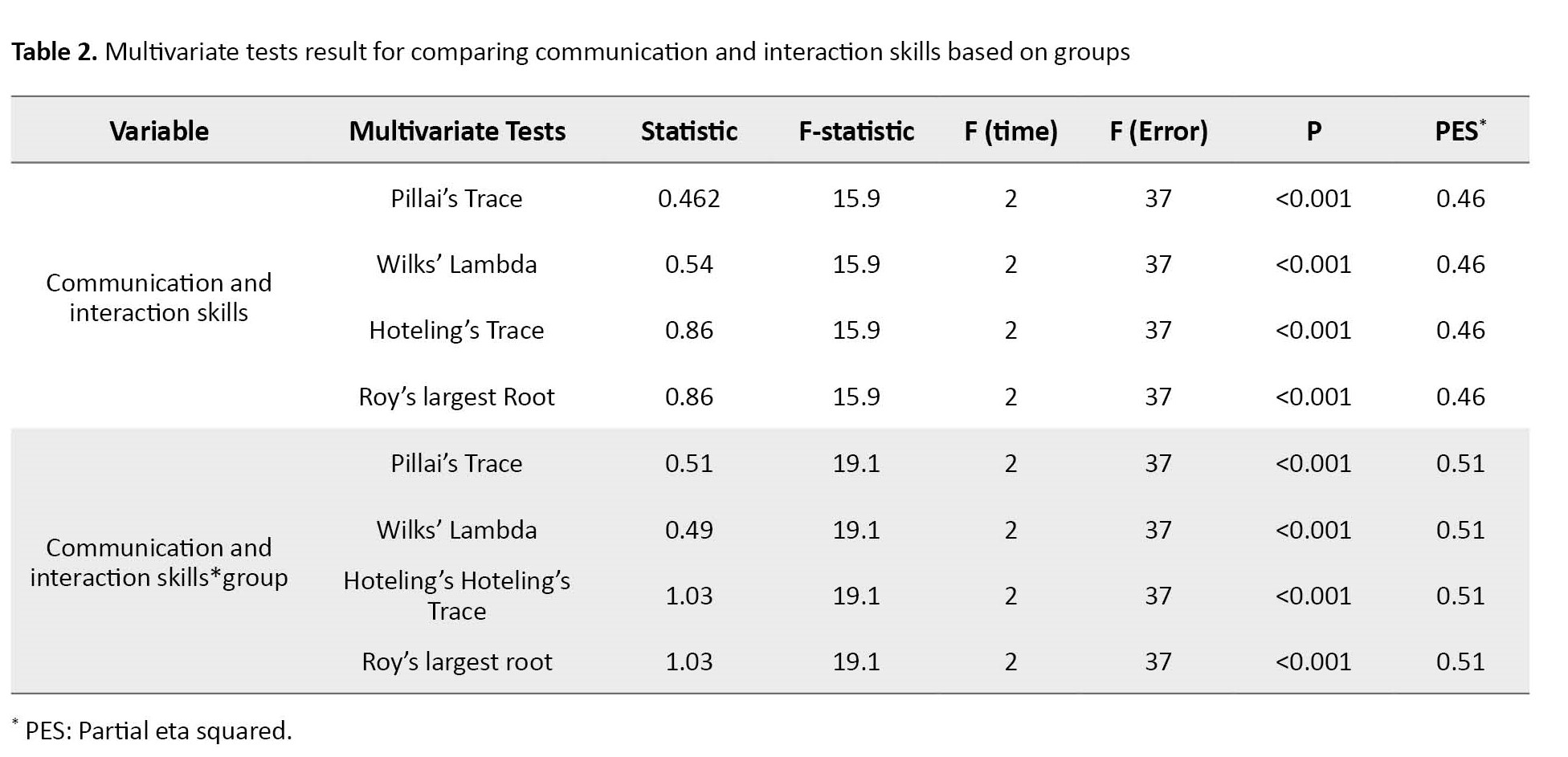

The outcomes of the multivariate test (Table 2) demonstrate that all four tests (Pillai’s trace, Wilks’s lambda, Hotelling’s trace, and Roy’s largest root) yield significant P values, indicating a significant main effect of communication and interaction skills (P=0.001).

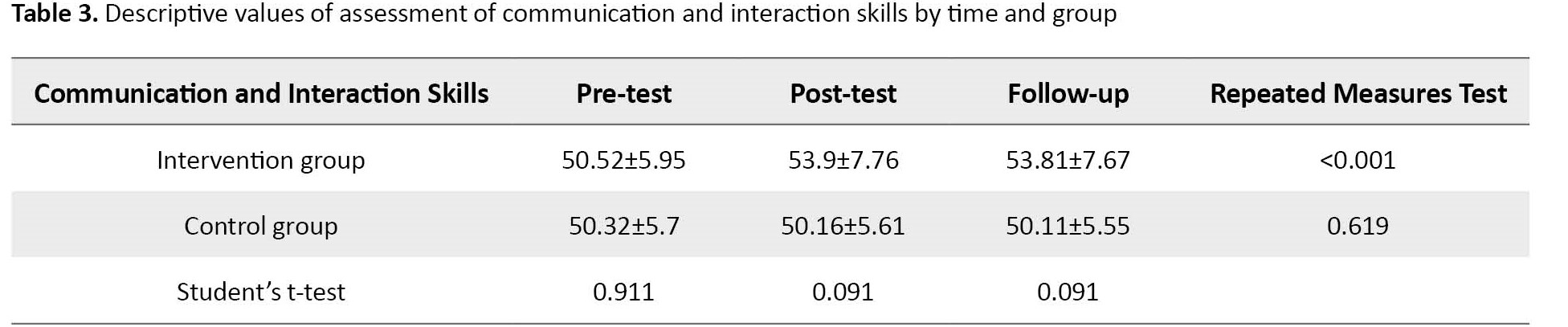

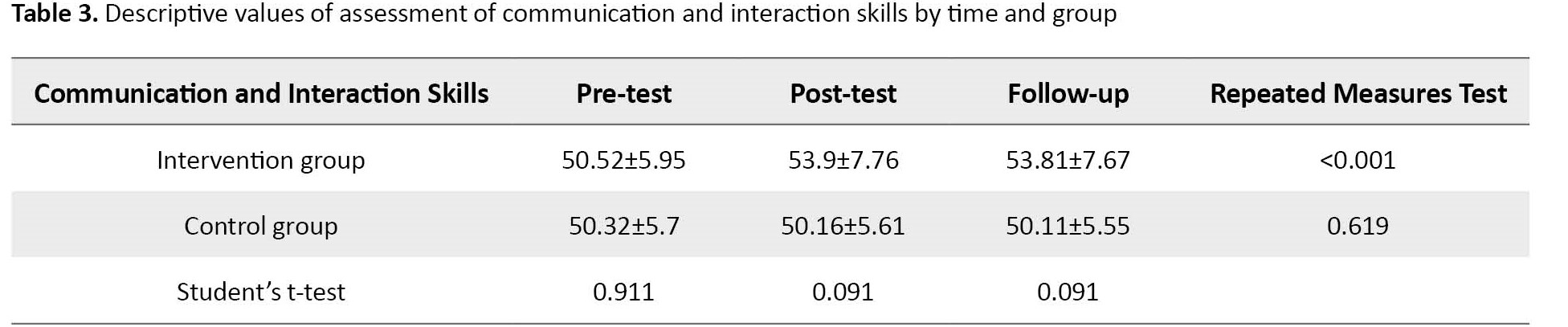

Furthermore, the interaction effect (communication and interaction skills×group) also showed significance in the multivariate test (P=0.001), revealing that variations in communication and interaction skills across the three assessments (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) are contingent upon group type (intervention or control). Given the substantial interaction effect observed in the mean scores of ACIS concerning the group, student’s t-tests (stratified by measurement time) and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (stratified by measurement group) were used to accurately ascertain the existing disparities between groups and measurement times. This approach was adopted to achieve a precise assessment of the situation. A substantial difference was observed in the mean ACIS scores between the pre-test and post-test assessments in the intervention group. While the mean scores for communication and interaction skills in the control group did not exhibit significant changes across assessment times (P>0.05), the comparison between groups over time for communication and interaction skills indicated a statistically significant enhancement (P<0.001) in the intervention group (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The results of this research illuminate the favorable effects resulting from the occupation-based self-determination intervention in 16 sessions, on the enhancement of total and subscale mean scores of the ACIS in the intervention group. The observed increase in mean scores implies a significant advancement in the communication and interaction skills of the participants. This result is consistent with the theoretical framework of the intervention, which was designed to empower individuals with ASD to actively engage in meaningful occupations and interactions.

The intervention’s emphasis on promoting self-determination skills appears to have played a pivotal role in fostering improved communication and interaction outcomes. By focusing on empowering participants to make choices, set goals, and self-regulate their actions, the intervention likely facilitated a sense of agency and self-efficacy among individuals with ASD. This newfound sense of control might have contributed to increased engagement and participation in various communication-based activities, resulting in improved ACIS scores.

Furthermore, the occupation-based nature of the intervention implies that participants were engaged in real-life, contextually relevant activities that demanded effective communication and interaction. This hands-on approach could have offered valuable opportunities to practice and refine these skills in meaningful contexts, translating into the observed rise in ACIS scores.

In the study conducted by Hojati Abed in 2020 to determine the impact of occupation-based interventions on the self-determination skills of adolescent girls at risk of emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD), it was found that these interventions are effective in increasing communication and interaction skills (as one of the sub-goals of the study) of adolescent girls at risk of emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD) and improves their ACIS scores [16].

The importance of these results is emphasized by the lack of previous research exploring the effects of self-determination interventions on the communication and interaction skills of individuals with ASD, as assessed using the ACIS. The research conducted by Alvarez et al. evaluated the outcome of animal-assisted intervention on nineteen 30 to 66 month-old children with ASD with ACIS. The results showed that after the intervention, the children made substantial progress in 12 out of 20 items in ACIS [17].

In the study conducted by Herbrecht et al., it was found that adolescents with ASD, who had severe problems in communication and interaction with others and had low levels of social participation, were able to show a significant improvement in social interactions by participating in sessions, including how to initiate interaction and giving feedback about their peers. The diagnostic checklist for pervasive developmental disorders was used to measure the progress of these teenagers in this research [18].

The scarcity of such research underscores the novelty and pioneering nature of this study. By pioneering the examination of the impact of occupation-based self-determination interventions on ACIS scores, our study contributes to the growing body of knowledge concerning effective interventions for enhancing communication and interaction skills among individuals with ASD.

The dearth of comparable studies highlights the need for further exploration into the potential of self-determination interventions as catalysts for communication and interaction skill development. Our study’s outcomes not only provide valuable insights into the positive outcomes of the intervention but also offer a promising foundation for future research in this domain. As the field continues to evolve, additional investigations can illuminate the mechanisms through which self-determination interventions exert their effects on communication and interaction skills, enabling the development of even more effective and targeted intervention strategies.

5. Conclusion

The occupation-based self-determination intervention had an effective impact and caused a significant improvement in the communication and interaction skills of autistic adolescents. Regarding social skill deficits that individuals with ASD struggle with, the presence of such interventions is critical in occupational therapy. Notwithstanding the usual occupational therapy interventions that adolescents with ASD have access to, it has been revealed that occupation-based self-determination interventions that target motivation, autonomy, assertiveness, and self-expression are effective in improving their communication and interaction skills.

Limitations and suggestions

Due to the very low number of girls with ASD compared to boys, this research was limited only to male adolescents and it is required to investigate this intervention in female adolescents as well.

Regarding the positive outcomes of this intervention in communication and interaction skills, occupation-based self-determination interventions can be a field of study for those who want to determine the effects of these interventions on other aspects of autistic individuals’ lives.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1401.478). Additionally, this clinical trial was registered duly in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (No. IRCT20230131057291N1). The parents of the students provided written informed consent before the assessments.

Funding

This research was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1401.478).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Supervision: Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei; Methodology: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat, Elahe Hojati abed; Investigation, Writing–review & Editing: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat, Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei, Elahe Hojati abed. Writing–original draft: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat; Funding acquisition, Resources: Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei, Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for generously contributing their time to complete the assessments. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the teachers and school staff for permitting the study to be conducted in their facilities.

References

Field and Hoffman defined self-determination as “a person’s ability to define goals and achieve them based on knowing and valuing oneself”. Their model deals with the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors that lead to self-determination and includes five components, know yourself, value yourself, plan, act, and experience outcomes and learn [1].

According to the latest study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2020, regarding the occurrence and indications of autism among 8-year-old children in eleven distinct regions across the United States, it was found that 1 out of every 36 children has autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Previous studies reported 1 in 54 children and 1 in 44 children with autism in 2016 and 2018, respectively. The prevalence figures vary significantly across various nations, with rates as low as under 0.2% in China and Italy, while South Korea reports a significantly higher rate of 2.7% [2]. The variation in autism prevalence is likely attributable to several factors, one of which is the nature of autism as a spectrum disorder, characterized by diverse traits that influence its definition [3].

In a person with ASD, the developmental process of self-determination is often hindered because the key features of this disorder may fundamentally weaken the self-determination effort [4]. Problems in executive function and adaptive behaviors are very common in autism [5]. Similarly, many adolescents with autism prefer rigid routines and feel uncomfortable in unfamiliar situations [4]. One of the key challenges faced by individuals on the spectrum is in social participation, defined as ‘involvement in a subset of activities that involve social situations with others’ [6]. Engaging in these social activities necessitates employing a collection of abilities, which occupational therapists have characterized as straightforward, easily observable actions with an inherent functional intent [7].

The diagnosis of autism requires the presence of deficiencies in both communication and social interactions. Holding a back-to-back conversation, using nonverbal communication behaviors (e.g. gestures), and developing and maintaining social relationships are certain instances of communication and interaction skills [8]. It appears reasonable to suggest that the self-determination status of students with autism can be substantially impacted by their social skills, as challenges in social interaction can constrain their ability to function independently [4]. However, in a study conducted by Lee et al. in 2021, many students with autism who participated in the study found that challenging themselves and developing social skills were crucial parts of their sense of belonging, which is one of the components of self-determination, and decided to compensate for their social communication problems using self-determination skills [9].

Promoting self-determination is vital for adolescents to achieve goals related to education, employment after education, social participation, and a better quality of life. By developing basic skills related to self-determination, adolescents are often more prepared to make decisions in life [4].

Few studies have reviewed the effect of self-determination interventions on adolescents with ASD. However, among these few studies, fewer number focus on the communication and interaction skills of these adolescents or even evaluated the outcomes with an occupational therapy-based instrument [10].

‘Assessment of communication and interaction skills (ACIS)’ is developed on the conceptual framework of the model of human occupation. According to this model, daily tasks consist of various distinct behavioral components referred to as “skills”. Skills are not considered a basic capacity. Rather, they refer to what happens during a performance. Three types of skills can be observed during job performance, motor, processing, communication, and interaction skills. Communication and interaction skills encompass visible actions employed to convey intentions and requirements, as well as organizing one’s conduct to engage with others. This conceptualization places the occupational therapists’ focus on what happens during social actions, instead of requiring them to infer it from the underlying capacity of the clients [11].

Objectives

This research aims to investigate the effect of occupation-based self-determination interventions on the communication and interaction skills of adolescent students with ASD in occupational performance level.

2. Materials and Methods

Trial design

This research is a single-blinded study, in which the assessors are blinded. This study was conducted as a randomized controlled trial in parallel groups and conducted from October 2022 to August 2023 in Tehran City, Iran. Two study groups of intervention and control were randomly assigned for the study.

Participants

This study involved male adolescent students attending an autism-specific educational complex located in Tehran City. The inclusion criteria included the students aged 13–18 years, ASD level 1 diagnosis by Gilliam autism rating scale third edition (GARS-III), and no other medical diagnosis. The exclusion criteria included the participants who had a sudden change in their medication (consuming selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]).

Setting

The research was conducted in a classroom in an autism-specific school situated in Tehran City from October 2022 to August 2023. The intervention sessions were conducted in a spacious classroom suitable for accommodating group sessions involving 7 to 10 students.

Randomization, blinding, and sample size

The study included 40 male high school students with autism, all of whom were enrolled in a specialized school for individuals with autism in Tehran City. These participants were randomized using a random-number table. The randomization process was conducted by an impartial individual who had no role in the intervention. Figure 1 shows the recruitment and participant flow throughout the trial. We determined the necessary sample size for each group by referring to previous research [12]. As a result, participants were divided into the intervention group (n=21) and the control group (n=19) through random sampling.

Procedure

At first, ACIS and demographic questionnaires were gathered from the students. All participants were assessed in pre- and post-intervention 1 week before and after intervention and follow-up (after 45 days) by a blinded assessor. To ensure adequate control and individualized attention to each participant in the intervention group, we employed random allocation, dividing them into three groups, each consisting of seven individuals. This approach is consistent with recommendations regarding group therapy group size based on available evidence [13]. The first author of the study conducted the intervention. Students in the intervention groups underwent a series of sixteen 60-minute sessions as part of the intervention program. At the beginning of each session, the participants were given clear instructions to implement the intervention plan.

Intervention program

The activities of the intervention program were tailored according to the participants’ requirements and preferences, inspired by the self-determination model proposed by Field and Hoffman [1]. The design of the intervention program included opinions from an expert panel consisting of two faculty members (of Iran University of Medical Sciences) having Ph.D.s in occupational therapy and two occupational therapists who have been working with the autism community for 10 years. Every panelist had expertise in the field of ASD. The intervention program was conducted through group sessions, comprising sixteen sessions, each lasting for 60 minutes. In each session, the participants engaged in activities related to the subject of the session. The objectives of previous sessions were reviewed at the onset of each session. The content of each session was rooted in the self-determination model proposed by Field and Hoffman. This model contains five components, including know yourself (first two sessions), value yourself (sessions 3 and 4), plan (sessions 5-7), action (sessions 8-10 and 12-15), and experience outcomes and learning (sessions 11 and 16). The participants were asked to work individually and in teams based on different tasks assigned to them, including drawing a picture of their dreams, creating a collage, making orange juice and serving it with cookies to other individuals, and preparing a salad. Meanwhile, the control group only participated in routine occupational therapy provided for every student at the school.

Instruments

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire was prepared to collect information about the age and grade of the students, their occupational therapy history, and medications.

Assessment of communication and interaction skills (ACIS)

The ACIS is an observational assessment tool specifically created to comprehensively assess an individual’s capacity for social interaction in meaningful social settings. The scale comprises 20 elements that assess communication and interaction skills, categorizing them into three theoretical domains, “physicality”, “information exchange”, and “relations”. Each element is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1–4), where a score of 1 indicates a significant deficiency leading to an unacceptable interruption in interaction, while a score of 4 indicates proficient skills that facilitate ongoing social interaction. The overall score is calculated by summing the scores of all the elements, ranging from 20 points (indicating severe deficiency) to 80 points (indicating competent performance) [11]. Kohlberg and his Swedish colleagues reviewed the psychometric properties of the test, and the evidence showed that the test has high construct validity, internal consistency, and rater reliability [14]. Keyvani et al. reviewed the translation and validity and reliability of this test in Iran [15].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of this study was divided into two main components, descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. In the descriptive section, data were presented using central indices, such as the mean, as well as measures of dispersion, such as standard deviation and standard error. To test the study hypotheses and assess the effects of time and group, we employed a combination of statistical methods. Specifically, the non-parametric chi-square test alongside parametric tests (repeated measures analysis of variance [ANOVA] and student’s t-test) was used. All statistical analyses were performed utilizing SPSS software, version 26.0.

3. Results

Initial analyses showed no significant differences in demographic characteristics among the participants (P>0.05). Table 1 presents an overview of demographic details and test scores for both groups of adolescents with ASD.

The outcomes of the multivariate test (Table 2) demonstrate that all four tests (Pillai’s trace, Wilks’s lambda, Hotelling’s trace, and Roy’s largest root) yield significant P values, indicating a significant main effect of communication and interaction skills (P=0.001).

Furthermore, the interaction effect (communication and interaction skills×group) also showed significance in the multivariate test (P=0.001), revealing that variations in communication and interaction skills across the three assessments (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) are contingent upon group type (intervention or control). Given the substantial interaction effect observed in the mean scores of ACIS concerning the group, student’s t-tests (stratified by measurement time) and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (stratified by measurement group) were used to accurately ascertain the existing disparities between groups and measurement times. This approach was adopted to achieve a precise assessment of the situation. A substantial difference was observed in the mean ACIS scores between the pre-test and post-test assessments in the intervention group. While the mean scores for communication and interaction skills in the control group did not exhibit significant changes across assessment times (P>0.05), the comparison between groups over time for communication and interaction skills indicated a statistically significant enhancement (P<0.001) in the intervention group (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The results of this research illuminate the favorable effects resulting from the occupation-based self-determination intervention in 16 sessions, on the enhancement of total and subscale mean scores of the ACIS in the intervention group. The observed increase in mean scores implies a significant advancement in the communication and interaction skills of the participants. This result is consistent with the theoretical framework of the intervention, which was designed to empower individuals with ASD to actively engage in meaningful occupations and interactions.

The intervention’s emphasis on promoting self-determination skills appears to have played a pivotal role in fostering improved communication and interaction outcomes. By focusing on empowering participants to make choices, set goals, and self-regulate their actions, the intervention likely facilitated a sense of agency and self-efficacy among individuals with ASD. This newfound sense of control might have contributed to increased engagement and participation in various communication-based activities, resulting in improved ACIS scores.

Furthermore, the occupation-based nature of the intervention implies that participants were engaged in real-life, contextually relevant activities that demanded effective communication and interaction. This hands-on approach could have offered valuable opportunities to practice and refine these skills in meaningful contexts, translating into the observed rise in ACIS scores.

In the study conducted by Hojati Abed in 2020 to determine the impact of occupation-based interventions on the self-determination skills of adolescent girls at risk of emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD), it was found that these interventions are effective in increasing communication and interaction skills (as one of the sub-goals of the study) of adolescent girls at risk of emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD) and improves their ACIS scores [16].

The importance of these results is emphasized by the lack of previous research exploring the effects of self-determination interventions on the communication and interaction skills of individuals with ASD, as assessed using the ACIS. The research conducted by Alvarez et al. evaluated the outcome of animal-assisted intervention on nineteen 30 to 66 month-old children with ASD with ACIS. The results showed that after the intervention, the children made substantial progress in 12 out of 20 items in ACIS [17].

In the study conducted by Herbrecht et al., it was found that adolescents with ASD, who had severe problems in communication and interaction with others and had low levels of social participation, were able to show a significant improvement in social interactions by participating in sessions, including how to initiate interaction and giving feedback about their peers. The diagnostic checklist for pervasive developmental disorders was used to measure the progress of these teenagers in this research [18].

The scarcity of such research underscores the novelty and pioneering nature of this study. By pioneering the examination of the impact of occupation-based self-determination interventions on ACIS scores, our study contributes to the growing body of knowledge concerning effective interventions for enhancing communication and interaction skills among individuals with ASD.

The dearth of comparable studies highlights the need for further exploration into the potential of self-determination interventions as catalysts for communication and interaction skill development. Our study’s outcomes not only provide valuable insights into the positive outcomes of the intervention but also offer a promising foundation for future research in this domain. As the field continues to evolve, additional investigations can illuminate the mechanisms through which self-determination interventions exert their effects on communication and interaction skills, enabling the development of even more effective and targeted intervention strategies.

5. Conclusion

The occupation-based self-determination intervention had an effective impact and caused a significant improvement in the communication and interaction skills of autistic adolescents. Regarding social skill deficits that individuals with ASD struggle with, the presence of such interventions is critical in occupational therapy. Notwithstanding the usual occupational therapy interventions that adolescents with ASD have access to, it has been revealed that occupation-based self-determination interventions that target motivation, autonomy, assertiveness, and self-expression are effective in improving their communication and interaction skills.

Limitations and suggestions

Due to the very low number of girls with ASD compared to boys, this research was limited only to male adolescents and it is required to investigate this intervention in female adolescents as well.

Regarding the positive outcomes of this intervention in communication and interaction skills, occupation-based self-determination interventions can be a field of study for those who want to determine the effects of these interventions on other aspects of autistic individuals’ lives.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1401.478). Additionally, this clinical trial was registered duly in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (No. IRCT20230131057291N1). The parents of the students provided written informed consent before the assessments.

Funding

This research was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1401.478).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Supervision: Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei; Methodology: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat, Elahe Hojati abed; Investigation, Writing–review & Editing: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat, Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei, Elahe Hojati abed. Writing–original draft: Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat; Funding acquisition, Resources: Mehdi Alizadeh Zarei, Mohammad Naghavi Kheslat.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for generously contributing their time to complete the assessments. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the teachers and school staff for permitting the study to be conducted in their facilities.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

- Ávila-Álvarez A, Alonso-Bidegain M, De-Rosende-Celeiro I, Vizcaíno-Cela M, Larrañeta-Alcalde L, Torres-Tobío G. Improving social participation of children with autism spectrum disorder: Pilot testing of an early animal-assisted intervention in Spain. Health Soc Care Community. 2020; 28(4):1220-9. [DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12955] [PMID]

- Bedell G. Measurement of social participation. In: Anderson V, Beauchamp MH, editors. Developmental social neuroscience and childhood brain insult: Theory and practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 2012. [Link]

- Chou, YC, Wehmeyer ML, Palmer SB, Lee J. Comparisons of self-determination among students with autism, intellectual disability, and learning disabilities: A multivariate analysis. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2017; 32(2):124-32. [DOI:10.1177/1088357615625059]

- Cole MB. Group dynamics in occupational therapy: The theoretical basis and practice application of group treatment. San Francisco: Slack Incorporated; 2017. [Link]

- Cuevas R, García-López LM, Olivares JS. [Sport education model and self-determination theory: An intervention in secondary school children (Croatian)]. Kineziologija. 2016; 48(1):30-8. [DOI:10.26582/k.48.1.15]

- Field S, Hoffman A. Steps to self-determination: A curriculum to help adolescents learn to achieve their goals. Student activity book. Washington: ERIC Publisher; 1996. [Link]

- Fisher AG, Griswold LA. Performance skills: Implementing performance analyses to evaluate quality of occupational performance. In: Schell B, Gillen G, editors. Willard and Spackman's occupational therapy. Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer; 2013. [Link]

- Forsyth K, Lai JS, Kielhofner G. The assessment of communication and interaction skills (ACIS): Measurement properties. Br J Occup Ther. 1999; 62(2):69-74. [DOI:10.1177/030802269906200208]

- Golson ME, Ficklin E, Haverkamp CR, McClain MB, Harris B. Cultural differences in social communication and interaction: A gap in autism research. Autism Res. 2022; 15(2):208-214. [DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2657] [PMID]

- Herbrecht E, Poustka F, Birnkammer S, Duketis E, Schlitt S, Schmötzer G, et al. Pilot evaluation of the Frankfurt Social Skills Training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009; 18(6):327-35. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-008-0734-4] [PMID]

- Hojati Abed E, Shafaroodi N, Akbarfahimi M, Zareiyan A, Parand A. Effect of occupational therapy on self-determination skills of adolescents at risk of emotional and behavioral disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021; 35:57. [DOI:10.47176/mjiri.35.57] [PMID]

- Khoushabi K, Keyvani S. [The assessment of comunication and interaction skills in psychotic patiens (Persian)]. Arch Rehabil. 3(3):12-9. [Link]

- Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, Fombonne E, Laska E, Lim EC, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168(9):904-12. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101532] [PMID]

- Kjellberg A, Haglund L, Forsyth K, Kielhofner G. The measurement properties of the Swedish version of the Assessment of Communication and Interaction Skills. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003; 17(3):271-7. [DOI:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00225.x] [PMID]

- Lei J, Russell A. Understanding the role of self-determination in shaping university experiences for autistic and typically developing students in the United Kingdom. Autism. 2021; 25(5):1262-78. [DOI:10.1177/1362361320984897] [PMID]

- Lindsay S, Varahra A. A systematic review of self-determination interventions for children and youth with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2022; 44(19):5341-62. [DOI:10.1080/09638288.2021.1928776] [PMID]

- Meltzer, L. Executive function in education: From theory to practice. New York: Guilford Publications; 2018. [Link]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 2023/09/2 | Accepted: 2023/09/27 | Published: 2024/02/15

Received: 2023/09/2 | Accepted: 2023/09/27 | Published: 2024/02/15